[dropcap]J[/dropcap]ames Jones’s The Thin Red Line is considered one of the finest combat novels to emerge from World War II. The second work in a trilogy alongside From Here to Eternity and Whistle, The Thin Red Line’s hard-hitting depiction of exhausted American soldiers battling the Japanese across Guadalcanal received glowing critical responses upon its publication in 1962. The Christian Science Monitor compared the book to Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage; Newsweek called it “a rare and splendid accomplishment…as honest as any novel ever written.”

At the beginning of the novel, Jones wrote: “Anyone who has studied or served in the Guadalcanal campaign will immediately recognize that no such terrain as that described here exists on the island. ‘The Dancing Elephant,’ ‘The Giant Boiled Shrimp,’ the hills around ‘Boola Boola Village,’ as well as the village itself, are figments of fictional imagination, and so are the battles herein described as taking place on this terrain. The characters who take part in the actions of this book are also imaginary…. [A]ny resemblance to anything anywhere is certainly not intended.”

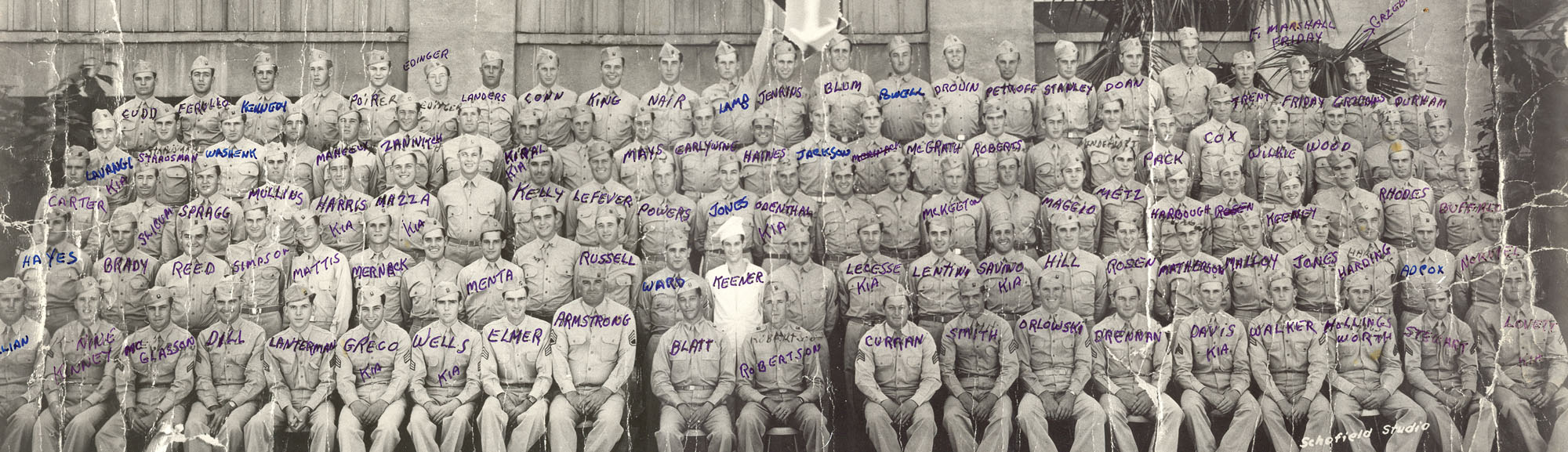

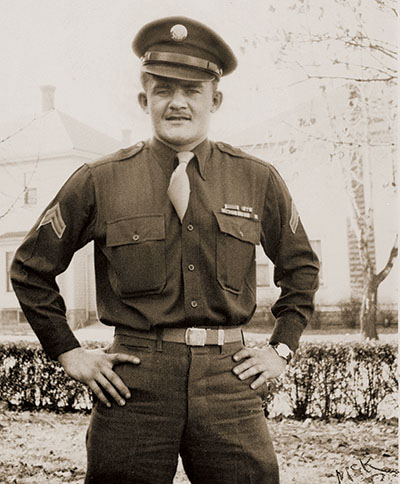

However, this is not completely true. Jones served on Guadalcanal as a corporal in Fox Company, 27th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division, and found fault with the official U.S. Army histories of the war. “You can read the history of a campaign in which you served, and find the history doesn’t at all tally with the campaign you remember,” he wrote. While working on The Thin Red Line, Jones told his editor, “No book has ever really been written about combat in wartime with real honesty.” So, like his literary hero, Thomas Wolfe, Jones used “only those things I have experienced myself, and those told me by men in my old company.”

Indeed, the actual experience of Fox Company so closely corresponds with The Thin Red Line that it is often difficult to determine where the novel leaves off and history begins.

On December 19, 1942, Fox Company’s commanding officer, Captain William Blatt, gathered his command group on “B” Deck of the U.S. Army transport Hunter Liggett. Blatt looked around at the men—including executive officer Lieutenant William Burn and Lieutenant Champ Jones, and noncommissioned officers like tough First Sergeant Frank Wendson, Sergeant William “Chubby” Curran, and Blatt’s temperamental clerk, Corporal James Jones. It had been 13 days since the company had shipped out of Schofield Barracks in Hawaii and rumors swirled about their destination. Now Blatt dropped a bombshell: they were going to fight on Guadalcanal, where American troops had been battling the Japanese since August.

Blatt, a Chicago lawyer in peacetime, had been in command of the company since before Pearl Harbor. He was generally unpopular; Jones recounted how the men felt that both Blatt and Lieutenant Burn took pains to keep the company’s enlisted men in their “proper place.” At times they showed open contempt for the captain. Just before the men shipped out from Hawaii, regimental headquarters had canceled their leave passes, but they angrily blamed Blatt and 15 of them went AWOL.

Jones, however, had a more compassionate view; Blatt had approved Jones’s requests to take English Literature classes at the University of Hawaii. The prospect of going into combat further softened Jones’s feelings for his commanding officer. “The more I think of Blatt, the more I am inclined to sympathize with him,” Jones wrote while aboard the Hunter Liggett. “Trying to keep 180 men satisfied, healthy & useful is impossible.” Jones closely based The Thin Red Line’s company commander, Captain James Stein, on Blatt.

But Blatt—along with everything else—seemed to disgust First Sergeant Wendson. A seasoned soldier with 10 years’ service, Wendson was a great athlete, the best shot in the company, and something of a legend in the regiment. He hid his genuine concern for the men behind a sarcastic and bitter outer shell, and often waxed cynical about the country he served: “Balls to a democracy like this! It’s politics and nothing else. Dog eat dog…. I just wish the Goddam Jap would win this war, just to see how these millionaire bastards would cringe on their bellies.” Jones adapted Wendson into central character First Sergeant Edward Welsh in his novel.

Instead of remaining on deck with the others after Blatt’s briefing, Jones returned to his bunk to record it in his journal. He had one grand ambition: “I hope, someday, to be a great author,” he wrote in 1942. In The Thin Red Line, Jones would base the intelligent but emotionally fragile character of Corporal Fife, the company clerk, on himself. Jones had been with Fox Company for two years. After failing to make the boxing or football teams—and badly injuring his ankle—Jones kept mostly to himself. His closest friend, a Kentuckian bugler and boxer named Robert Lee Stewart, had been promoted, busted, and sent to the stockade multiple times before being reassigned out of the company. Jones fell back on his solitary literary aspirations, and later adapted Stewart into The Thin Red Line’s Private Robert Witt.

By December 30, the Hunter Liggett was anchored off Guadalcanal and Fox Company prepared to disembark. Word circulated that Japanese planes had been seen approaching Guadalcanal. Jones prepared by securing a dog tag to each wrist and ankle, so that if he was blown up someone could still identify a piece of his body. The soldiers swung over the transport’s sides and clambered down the cargo netting to the waiting landing craft.

Fortunately for Jones and his comrades, the company made it ashore before the Japanese aircraft reached the area. The men watched in horror and fascination as the enemy bombed the American transports. Jones remembered that a “loaded barge coming in took a hit and seemed simply to disappear.” After the Japanese planes buzzed away, men fished out their wounded and dying comrades. Jones drew from the incident in The Thin Red Line, describing its effect on the men pulled from the water:

They had crossed a strange line; they had become wounded men; and everybody realized, including themselves, dimly, that they were now different. Of itself, the shocking physical experience of the explosion, which had damaged them and killed those others, had been almost identically the same for them as for those other ones who had gone on with it and died. The only difference was that now these, unexpectedly and illogically, found themselves alive again.

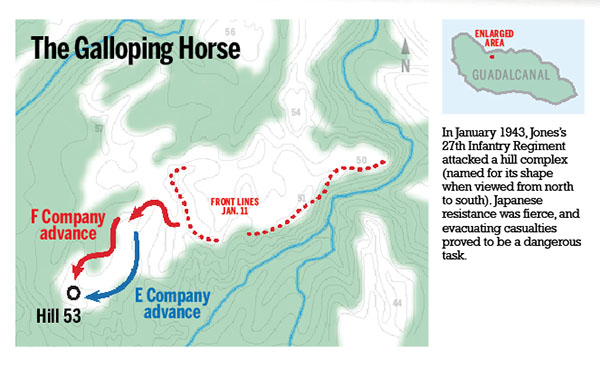

The regiment spent two weeks acclimating to Guadalcanal’s terrain and climate—as well as to nightly bombing raids—before division headquarters ordered them into action. They were tasked with capturing a hill complex dubbed the “Galloping Horse” for its shape in aerial photographs. In The Thin Red Line, the corresponding fictional terrain became the “Dancing Elephant.”

Second Battalion—comprised of Easy, Fox, and George companies—would play a crucial part of American forces’ January 1943 offensive, which aimed to gain ground west of the Matanikau River and launch a final campaign to drive the Japanese off the island.

The battalion was initially placed in reserve; Jones and his comrades had ringside seats to the first two days of combat, as 3rd Battalion attacked westward along the “Galloping Horse.” After capturing Hill 52 at the center of the hill mass, the men continued pushing west until enemy fire stymied their advance.

Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Mitchell, 2nd Battalion’s commanding officer, prepared to take over the assault. He assigned Fox Company the toughest job: pushing forward into the teeth of Japanese defenses. Their attack would be aimed at capturing two features: a left-hand ridge to their southwest, then a distant ridge further west. Fox Company was to next press on to take Hill 53.

At dawn on January 12, a thin line of soldiers in olive drab herringbone twill fatigues, their eyes wide and mouths open against the concussion of their artillery bombardment, clutched their rifles and hugged the dirt as shells whistled overhead and exploded. Fox Company waited for the attack order. The terrain ahead of them consisted of open, rolling hills, clearly visible from elevated observation points behind. From one such point, division commander Major General J. Lawton Collins and corps commander Major General Alexander M. Patch waited to observe the attack; word spread that U.S. Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, Admiral Chester Nimitz, and Admiral Bill Halsey were on the island and could be watching, too.

At 6:30 a.m., the pre-assault bombardment ceased and Blatt sent Lieutenant Champ M. Jones’s platoon forward. “I was able to move down a hill about 100 yards and I stopped in some tall grass,” Champ Jones later recalled. “I stayed in place for a while and looked for members of my platoon since I was in charge. In looking for my platoon…I stood up enough to be wounded” in the arm, chest, and shoulder by Japanese machine-gun fire.

As Champ Jones fell, Japanese small-arms and mortar fire tore into Fox Company from the surrounding hills. Despite a flurry of casualties, the company captured the forward ridges. James Jones admitted being “scared shitless” during the assault. He worked to keep up with Blatt, who had begun to earn his men’s respect by staying forward, seemingly unafraid of exposing himself to danger.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Colonel Mitchell, no doubt feeling pressure from the brass observing his battalion’s attack, telephoned Blatt and complained that Fox Company had veered too far right, exposing their flank. Mitchell committed Easy Company to plug the gap and ordered Blatt to continue attacking across the wide, open ground. But Japanese fire from the distant western ridge kept Fox and Easy Companies pinned down; the men desperately sought shelter in shell holes or behind folds in the ground.

Mitchell demanded that Blatt continue to attack westward. Instead of going straight into the buzz saw and losing more men, Blatt wanted to pull Fox Company back, move through the jungle, and concentrate an assault on Hill 53 from the north. A furious Mitchell demurred, instead ordering Blatt to continue the frontal attack. With Japanese fire tearing into his men, Blatt made a critical decision. He flatly refused Mitchell’s order.

Jones later dramatized the exchange in a pivotal scene of the novel, when Captain Stein refuses the same direct order from the novel’s Lieutenant Colonel Gordon Tall.

“Colonel, I refuse to take my men up there in a frontal attack. It’s…suicide! I’ve lived with these men two and a half years. I won’t order them all to their deaths. That’s final. Over.”…Tall was stupid, ambitious, without imagination, and vicious as well. He was desperate to succeed before his superiors. Otherwise he could never have given such an order.

Meanwhile, Blatt’s company command post, located behind a low ridge, came under Japanese mortar fire. One of the shells exploded near Jones, throwing him through the air and wounding him in the head. Jones mirrored the incident in The Thin Red Line, with his alter ego, Corporal Fife:

He heard the soft ‘shu-u-u’ of the mortarshell for perhaps half a second. There was not even time to connect it with himself and frighten him, before there was a huge sunburst roaring of an explosion almost on top of him, then black blank darkness. He had a vague impression that someone screamed but did not know it was himself.

“I came to…several yards down the slope, bleeding like a stuck pig and blood running all over my face,” Jones later recalled. “As soon as I found I wasn’t dead or dying, I was pleased to get out of there as fast as I could.” He cautiously walked back to the hospital, where medics treated him with morphine and sulfa powder. In the novel, Fife again channels Jones’s feelings:

Fife…suddenly realized that he was free. He did not have to stay here any more. He was released. He could simply get up and walk away—provided he was able—with honor, without anyone being able to say he was a coward or courtmartialing him or putting him to jail. His relief was so great he suddenly felt joyous despite the wound.

Under the relentless tropical sun, afternoon bled into early evening as the companies tried again in vain to capture Japanese positions on the ridges. Captain Charles W. Davis, a strapping, athletic Alabamian, was the battalion executive officer and volunteered to assist the men. Davis, who became the model for The Thin Red Line’s Captain John Gaff, braved over 300 yards of exposed ground in his dash from the battalion command post to the frontline.

Heavy fire from a hidden Japanese strongpoint on the reverse slope of the distant ridge brought the American assault to a standstill. Davis realized they had to locate that enemy position and led two others in a crawl along the east side of the ridge toward it. The Japanese spotted the trio, killing one of them with a burst of machine-gun fire. But Davis found the strongpoint.

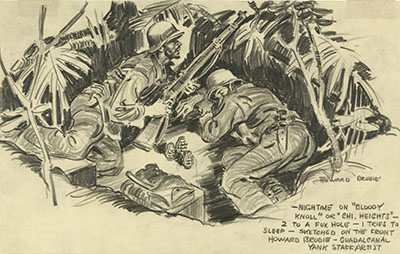

After making several attacks, men in the assault companies were exhausted and, in Guadalcanal’s extreme heat and humidity, dehydrated, too; no water had been sent to the frontline since the early morning and the men were on the verge of collapsing. Nevertheless, Mitchell ordered another attack; it failed. With darkness falling, the troops established a defensive perimeter for the night.

At daybreak, Mitchell walked from his command post to the frontline, where Fox Company awaited his orders. Rather than sending them forward yet again, Mitchell ordered them north through the jungle to take the “Horse’s Head,” as Blatt had repeatedly urged the previous day. A small team from Fox Company, including Sergeant “Chubby” Curran, volunteered to eliminate the Japanese strongpoint. Jones later novelized Curran as “Skinny” Culn, a “round, red-faced, Irishman…an easygoing sort…but a careful, well-grounded soldier.”

“After we had gone over the crest of the hill a machine gun opened up,” Curran remembered. “We were in the high grass on the saddle. Snipers hidden in ‘spider holes’ then opened up and got three of my men right through their helmets. Two were dead and [another] wounded.” The GIs managed to crawl within 25 yards of the enemy strongpoint, but ran out of grenades. When one of his men was wounded, Curran took him back down and asked for volunteers to get more grenades and finish the job.

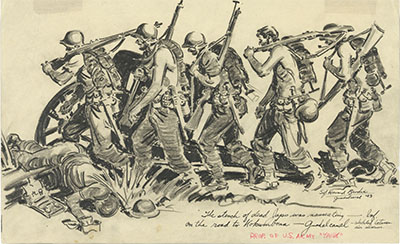

Davis volunteered to lead Curran’s survivors back up the hill for the second attempt on the strongpoint. The next 20 minutes proved decisive.

The assault party crawled forward on their bellies; when they were within 10 yards of their objective, the Japanese showered them with grenades. By a stroke of luck, the explosives were defective. One grenade landed between Curran and Davis; “It didn’t go off; however, we did!” Davis recalled. The GIs threw their own grenades and charged the Japanese positions. Davis remembered “bolting from the prone to a running position, following our grenades…we made a charge much like those pictured during the Civil War.” Davis stood up, his rifle at hip level, and squeezed the trigger. Jammed. He threw the rifle aside and drew his .45-caliber pistol. Jones later described the assault in the novel:

“Go in! Go in!” Gaff cried, and in a moment all of them were on their feet running. No longer did they have to fret and stew, or worry about being brave or being cowardly. Their systems pumped full of adrenaline to constrict the peripheral blood vessels, elevate the blood pressure, make the heart beat more rapidly, and aid coagulation, they were about as near to automatons without courage or cowardice as flesh and blood can get. Numbly, they did the necessary.

The storming party wiped out the Japanese in vicious close-quarter fighting. Division commander Major General J. Lawton Collins witnessed the attack: “As he led this charge, Davis was silhouetted against the sky in clear view of the bulk of the battalion, as well as the Japs. His action had an electrifying effect on the battalion.” Inspired, Easy Company advanced up the hill to help wipe out any remaining Japanese resistance.

At about the same time, Fox Company assaulted the enemy positions on the ridge to the north. Jones’s comrades later described to the still-recovering corporal their frenzied and chaotic attack: as the Americans overran the Japanese defenders, they went “kill-crazy,” Jones recalled. “They bayoneted sick & wounded Japs. They shot them when they came out naked, hands in air.” Fox Company successfully captured the ridges, and division headquarters pulled the regiment off the line for a well-deserved respite.

Ten days after he was wounded, Jones returned to a Fox Company that felt different from the unit he had known. Blatt was gone; Mitchell had relieved him of command for his refusal to obey the attack order. Casualties had also changed the ranks—sergeants had assumed command of two of the platoons, and more than a quarter of Fox Company had been killed or wounded. And in what felt like a personal betrayal by First Sergeant Wendson, Jones discovered that another soldier had replaced him as company clerk. Jones was assigned to a rifle platoon in time for the second offensive toward the Poha River and the Japanese base at Kokumbona.

Unbeknownst to the Americans, the Japanese had decided to evacuate Guadalcanal. Consequently, the regiment’s offensive on January 22 was stunningly successful—they encountered only desperate enemy rear guards or disorganized units in flight. After another battalion captured Kokumbona—“Boola Boola Village” in Jones’s novel—Fox Company carried on in a blur of rapid advances. At night, the men bivouacked on grassy hillsides.

The unexpected swiftness of the advance stretched the regiment’s supply lines, and Jones remembered three days and nights without supplies, “drinking water from shell holes,” with only two four-ounce D-ration chocolate bars per platoon. He also noted—with disgust—that Lieutenant Burn had a 12-ounce C-ration can at his command post.

The unit reached the Poha River in two days. For Fox Company, that marked the end of their combat on Guadalcanal. They spent months recuperating and training before they traveled up the Solomon Islands to fight in the New Georgia campaign. But Corporal James Jones was not among them.

Jones’s right ankle had troubled him since Hawaii, and he took to firmly taping it for marches or maneuvers. But in late March, while walking with Wendson, Jones reinjured the ankle. Wendson ordered him to have it examined, adding in his usual style: “If it’s as bad as what I saw, you got no business in the infantry.” The medics agreed, and Jones left Fox Company forever. But he carried in his mind the events, the men, and the drama, and would immortalize his outfit in The Thin Red Line.

The novel as an art form often reveals fundamental human truths through fiction. Conversely, Jones knew history sometimes obscures truth, writing that “the whole history of…World War II has been written, not wrongly so much, but in a way that gave precedence to the viewpoints of strategists, tacticians and theorists, but gave little more than lip service to the viewpoint of the…fighting lower class soldier.” Aside from its literary merits, The Thin Red Line places the frontline soldier’s viewpoint front-and-center in its vision of a world gone mad. Jones himself acknowledges the subjective nature of interpreting the human experience in the last line of his novel:

One day one of their number would write a book about all this, but none of them would believe it, because none of them would remember it that way.✯

This story was originally published in the January/February 2017 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.