The ‘Rage Of Battle’ forever haunted some veterans

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n 1862, Owen Flaherty left his wife and son in Terre Haute, Ind., and joined the 125th Illinois Infantry. He was, by all accounts, a quiet and easygoing man, well-liked and quick to share a laugh and a drink with his comrades. Until the Battle of Stones River, that is. After that horrendous four-day battle, fought from December 31, 1862, to January 3, 1863, Flaherty reportedly grew increasingly morose, sinking into what one soldier called a “deep study all the time.” He had difficulty sleeping, and was constantly troubled by nightmares. Owen sank further into despair the next year and a half, until a ground-shaking artillery barrage at Resaca, Ga., in May 1864 sent him irrevocably over the edge. He wandered off at all hours, ate and slept alone, and was quick to anger. Once, while on picket duty, he ran into camp shouting that the enemy was coming, when no hostile force was anywhere near.

Postwar life in Terre Haute was no better for Flaherty. He lost a job at the local blast furnace apparently because he could not concentrate. His anger and irritability drove his son permanently from home, and his violent tendencies brought the police to his door on a number of occasions. According to his wife, he “imagined they were firing on him with guns.” His sudden and uncontrollable temper would flare at any mention of the war. Unemployable, un-predictable, and highly volatile, Flaherty took to wandering the streets.

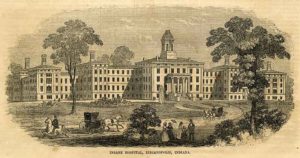

Eleven years after the war ended, he was sent to the Indiana Hospital for the Insane in Indianapolis and diagnosed with “acute mania.” Since the state facility made no provision for keeping or treating “chronic cases,” Flaherty was remanded to the poorhouse after only a few months. Here, a medical examining board noted his predisposition toward irrational anger and violence, as well as his delusional “fear from imaginary persons who intend to kill him.” They attributed his condition to “some mental shock probably sustained in the service.”

Today, Flaherty would most certainly be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

[dropcap]P[/dropcap]TSD formally entered the lexicon of psychological diagnoses in 1980, as “a delayed-stress syndrome which is caused by exposure to combat and can produce symptoms of rage, guilt, flashbacks, nightmares, depression, and emotional numbing, and can lead to a variety of grave social and psychiatric problems—from unemployment to suicide.” It is important to emphasize the “delayed” aspect of the diagnosis. While it is common for people to experience a psychological response to a traumatic incident—an auto accident, a robbery at gunpoint—those affected by PTSD suffer its effects long after the event, or events, that caused it.

While the technology of warfare has changed over the millennia, the psychological effects of bloody confrontation have been ever-present, and sufficient documentation exists to conclude that Civil War soldiers suffered from PTSD. This evidence includes medical reports, newspaper and family accounts, and the letters and diaries of the soldiers themselves.

Clearly, the Civil War provided a perfect storm of conditions that could trigger PTSD. It was the last American conflict to be fought in a traditional manner, but in the face of devastating modern technology. The accuracy of long-range cannons and rifled weapons ensured a greater likelihood of death or horrible mutilation than ever before, as men were repeatedly marched in formation across miles of open fields while enemy fire cut them down, as a soldier in the 151st New York Infantry wrote in his diary, “like sheaves of wheat.” Those not slain outright often suffered lingering or crippling wounds, in a time and place where the most expedient medical solutions were crude and inadequate. By war’s end, hundreds of thousands had been killed or wounded, while innumerable others had clearly fallen victim to catastrophic psychological trauma.

It was a war for which most American soldiers were mentally and emotionally unprepared. This was the Victorian age, a time when standards of manly conduct were set inordinately and unrealistically high. Battle was popularly portrayed as a noble, romantic pursuit, offering a man the opportunity for glory or, in the parlance of the period, “a good death.” Although the North was turning toward industrialization, most of the soldiers on both sides were country youths with little or no knowledge of the world beyond their homes, farms, and towns. For many, their only exposure to war had come from listening to the sanitized reminiscences of their fathers or grandfathers, or reading such tales of chivalry as Ivanhoe and Idylls of the King. As they would discover, this was far from the knightly combat described in Scott and Tennyson, nor was it their fathers’ or grand-fathers’ kind of war.

[dropcap]P[/dropcap]erhaps the most common circumstance in which a soldier could suffer PTSD was participation in combat. It was not uncommon for naive recruits to look forward with enthusiasm to their first battle. “I was tormented by…fear the fighting would all be over before I got into it,” one Confederate recalled—angst shared by countless others. Few could have imagined the shock of just being within earshot of a fight: the deafening roar of the guns, the insidious whine of the bullets, the piteous screams of the wounded. And when their turn came to enter the fray, nothing could have prepared them for what one soldier described as “the awful shock and rage of battle.” Confederate John Dooley’s journal paints a vivid picture: “Brains, fractured skulls, broken arms and legs, and the human form mangled in every conceivable and inconceivable manner….At every step they take…their feet are slipping in the blood and brains of their comrades.” One Union soldier despaired of describing the scene: “The half of it can never be told—language is all too tame to convey the horror and meaning of it all.”

Nor could they have predicted the effect on their psyches of its aftermath—a blasted smoke- and sulphur-infused expanse of human desolation, thick with the sights, sounds and smells of dead, maimed and dying men. A Union colonel surveying the field after Malvern Hill wrote: “A third of them were dying, but enough were alive to give the field a singularly crawling effect.”

Soldiers treated for battle wounds were prime candidates for PTSD. The wounds themselves were terrible. Firearm technology during the Civil War saw the widespread use of the Minié ball, a French development that wasn’t a ball at all, but a hollow-based, conical soft-lead projectile typically ranging from .58 to .69 caliber. Whereas a standard musket ball might break a bone in its course, the Minie ball tended to shatter bones and pulverize flesh, to the extent that an affected limb normally had to be amputated. Even in cases where the arm or leg might be saved, the surgeons were so overworked—and in some cases, unskilled—that amputation became the standard treatment. Shock from the procedure itself killed a number of soldiers. Those who survived faced the likelihood of infection, since the concept of sterilizing instruments, or even the routine washing of hands, was still years in the future. Some soldiers who lived through the operation found themselves addicted to the morphine or opium given to ease the pain.

Simply witnessing the horrific scene at a field hospital made an indelible impression. As described by one chronicler: “[W]ounded men in every condition conceivable—shattered and shrieking—were brought in on stretchers….With an unendurable stench pervading the air, mangled men, some with limbs already rotted by gangrene, covered the floor and flowed out into the yard as blood-spattered surgeons hoisted the next screaming victim onto the ‘operating table’…and, as their assistants held the struggling patient down, sawed away furiously to amputate an arm or leg. Buckets of blood and piles of amputated arms, legs, and feet littered the ground, and the groans or haunting death appeals of the mortally wounded rang forever in the ears of all those who were there.”

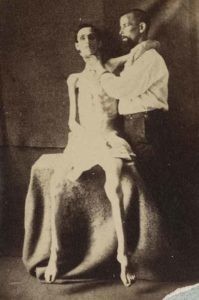

For those who survived the surgery, the homecoming itself offered its own kind of nightmare, exacerbating the stressors under which a victim of PTSD was already suffering. Most soldiers had made their living through physical labor prior to the war. Whether a man had been a farmer or factory hand, teamster or construction worker, blacksmith or coal miner, the loss of a limb signified the end of his livelihood. His options were few: a state-run soldiers’ home, the county poorhouse, or the street. For an already traumatized veteran finding himself crippled, unemployed, and unable to support himself or his family, reduced to begging or living “on the dole,” the psychological impact was devastating.

Soldiers need not have suffered physical injury to fall victim to PTSD; proximity to the slaughter could prove sufficient. “More than the physical injury in these cases,” wrote one physician of the period, “there seems to be [a] psychical effect…such as horrible sight of suffering, the cries of the injured, the agony of the mangled bodies, and all sorts of horrible scenes; in addition to that, even if not injured himself, come the terror of personal danger, the mental agony, the fright, etc., affecting the victim profoundly.”

For many seasoned veterans as well as green recruits, the inability to come to terms with the experience of battle became insurmountable, and they succumbed to PTSD. In his excellent book Shook Over Hell: Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam, and the Civil War, Eric T. Dean writes: “Although men concentrated on the task at hand and put personal safety aside, they still witnessed and reacted to— even if belatedly—horrific scenes of slaughter, and these sights and memories took an eventual toll.”

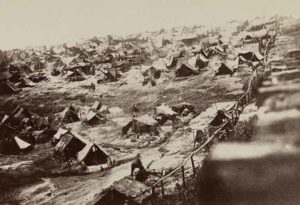

There were circumstances beyond exposure to combat in which a soldier could become a sufferer of PTSD. The unimaginable horrors endured by those who were captured —or, “gobbled,” as the saying went—and sent to prisoner-of-war camps often exceeded those of combat. Many captured soldiers on both sides considered remand to a prison camp tantamount to a death sentence; even if they survived, they were often physically and psychologically damaged for life. There was none of the decisiveness of battle, simply the slow, agonizing passage of day after hellish day in captivity, with a future that held nothing but illness, starvation, and slow decline. Unrelieved hunger and thirst, exposure to extremes of weather, and brutal treatment by both guards and fellow inmates in such pits of misery as Libby, Elmira, Camp Douglas, and Andersonville comprised a purgatory from which death was often the only escape.

Many prison camp survivors exhibited stressors of PTSD. Erastus Holmes, a quartermaster sergeant in the 5th Indiana Cavalry, bore the classic symptoms for the rest of his life. He was captured by the Confederates in July 1864. After a brief incarceration in Florence, S.C., he was transferred to Andersonville, where he endured terrible hunger and slept in a water-soaked hollow in the ground. Not surprisingly, he suffered from various diseases, and at war’s end, weighed only 85 pounds—around half of what he had weighed when captured. On his return home, he could barely walk, and according to his sister, “was the poorest looking thing I ever saw.” He relived the horrors of his experience over and over, both internally and verbally, constantly talking to himself, gnashing his teeth, tensing his muscles, and suffering “spells” of mental anguish. He created a detailed model of the prison camp in his back yard, repeatedly insisting his neighbors and family tour it. Unable to sleep, he ate obsessively, at all hours of the day and night. According to his daughter, Holmes “would feed all the tramps he could find…and set out pies and cakes for the birds….It seemed as though he could not bear to see anything that seemed to be hungry.”

Twenty years after the end of the war, Holmes suffered a complete breakdown, and could remember nothing of what had occurred in his life after Andersonville. He was admitted to the Indiana Hospital for the Insane, where he remained until his death in 1910.

Between 1861 and 1865, some 400,000 men had been “gobbled,” of whom more than 50,000 had perished. Andersonville alone buried 13,000 of its 45,000 prisoners, while the death toll at the Union prison at Elmira—or, “Hellmira,” as its prisoners called it—reached 24 percent. Many of the survivors carried the mental scars of PTSD, in a world that had no idea what to do with them. Erastus Holmes was one of countless sufferers for whom society’s solution was either jail or an insane asylum.

Even for those who survived combat and avoided capture, proximity to disease and its effects were constant assaults on their stability. Typhoid, smallpox, cholera, scurvy, measles, malaria, pneumonia, and simple infection were rampant in the camps of both armies, eventually killing twice as many soldiers as those who died by shot or shell. Among the most common ailments—frequently the results of consuming spoiled food or stagnant water—were dysentery and diarrhea, which afflicted approximately 78 percent of soldiers. As one wrote in a letter home: “Sickness causes more deaths in the army than Rebel lead….A man gets sick and unless he has a strong constitution, he sinks rapidly to the grave.”

As Dean wrote: “Civil War soldiers could be haunted by the deaths of comrades, especially when they died far from home and did not receive decent burials.” Witnessing the sickness that surrounded them daily, seeing messmates perish, and knowing that they themselves might soon succumb, took a terrible mental toll on the soldiers, and lingered long after the war had ended. Ben R. Johnson, a 6th Michigan infantryman whose outfit had been posted in the Louisiana swamps, later wrote of the effects of swamp fever, which he called “the enemy….His slimy, cold, and merciless hand bore down upon us until we moaned in our anguish and prayed for mercy….Many comrades were stricken down in the midst of life and laid away under the accursed soil of the swamp.”

Sometimes the most basic functions relating to a soldier’s life could induce PTSD symptoms. Infantry soldiers in the Civil War generally traveled by foot, conceivably covering thousands of miles during the course of their service. Marching, while a deceptively simple task on the surface, frequently presented hardships for which the soldiers were ill-prepared. As one Yankee would write: “Walking ten or twelve miles a day will hurt no one, but walking 12 miles a day and carrying a knapsack full of clothing, a blanket, a half tent, several days rations, gun, ammunition, &c, is the hardest kind of work.” He could have added that the trek was often made under punishing conditions—a brutal Southern sun, freezing Northern snow—and without the appropriate clothing, equipment, or provisions. Dehydration was a significant threat; a number of soldiers collapsed or died on the march from lack of sufficient water or heat stroke. Shoes wore out, leaving soldiers—especially Confederates, who had a footwear problem from the outset—to suffer with every step. “Most of our marches,” one Southern surgeon wrote to his wife, “were on graveled turnpike roads, which were very severe on the barefooted men and cut up their feet horribly.”

Marches could extend for days or weeks, continuing well into the night; the soldiers never knew when the misery would stop. And when they made camp, it could well be in inhospitable surroundings. Mud was a common enemy. One Confederate wrote, “Space forbids my describing the length, depth and breadth of the mud.” As bad as were the rain and mud, the cold could be worse. “I had gotten chilled,” recalled one Rebel, “and my teeth were glued together and a feeling of complete wretchedness came over me.” “Last night very cold,” an Indiana soldier recorded in his diary, “did not sleep well…woke from a dream crying.” And when a march finally ended, it was often to deliver the exhausted men to battle.

Marching and the related effects of constant exposure to the elements could have such a debilitating effect on soldiers that after the war, a number of them applied for disability pensions listing “hard marching,” “sunstroke,” or “exposure” as the cause. In many cases, the claims were approved.

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]ilitary physicians were mandated, as part of their responsibilities, to recognize and diagnose mental disorders among the troops. The science of psychology was still years in the future, however, and generally neither the military hierarchy nor the medical profession understood, or was disposed to make allowances, for soldiers whose experience in war had mentally incapacitated them. The symptoms were frequently not recorded or were improperly identified, commonly dismissed with such facile diagnoses as “acute mania,” “soldier’s heart,” “nervous shock,” “railway brain,” “melancholy,” “nostalgia,” “dementia,” “hysteria,” “feeble will,” “moral turpitude,” or simply “cowardice.”

Without today’s understanding of PTSD as a legitimate disorder, its wide range of symptoms made a viable diagnosis impossible. Chronicler Dean observes: “[T]heory concerning these traumatic neuroses remained highly speculative and inconclusive.” The behavioral patterns associated with PTSD were often seen as a moral lapse, for which shaming and hard campaigning were the accepted treatments. The Union army—anxious to keep as many men armed and in active service as possible—tended to label sufferers as shirkers and malingerers. They were returned to duty, unless “manifest imbecility or insanity” could be clearly established. In 1914, neurological pioneer and former Civil War surgeon S. Weir Mitchell wrote: “I regret that no careful study was made of what was in some instances an interesting psychic malady, making men hysteric and incurable except by discharge.”

One frustrated physician of the period expressed the difficulties in forming an all-inclusive diagnosis for the disparate indicators of PTSD, now so well recognized: “In the study of traumatic neurosis…no elements will impress the neurological student more than the diversity of theories presented: the wide range of interpretation, their multiplicity of symptomology, incongruities of description, lack of definite detail, their subjectivity presenting…vagaries difficult of comprehension and seemingly full of contradiction.”

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]t the end of the war, thousands of Union veterans or their families applied for financial aid from the state and federal governments (Confederate veterans were ineligible for U.S. government pensions). It is an indication of the lack of knowledge relating to war-induced mental disorders at the time that—while compensation was allotted to those who had suffered physical injuries during the conflict—practically no money was forthcoming for victims of mental trauma. Years later, this would change, and sufferers of mental disorders—including aspects of PTSD—would be given financial aid, provided a panel of doctors agreed. But at the time, they remained an unacknowledged tragedy of the war.

The responsibility for caring for those affected by PTSD generally fell upon the victims’ families. Depending on the symptoms exhibited by the suffering veteran, this could be a frustrating and at times impossible task. Those affected often took to drink, which frequently led to violence. Insomnia was not uncommon, with the sufferer dazedly roaming the house or yard. This could turn frightening should he be armed and looking for an imaginary foe. Medical records and family accounts provide numerous accounts of troubled veterans who slept with a gun, knife, or ax for protection against “enemy attack.” Ultimately, unable to cope and with no end in sight, the family would have little choice but to have him committed to an already overcrowded state or county mental facility.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]t is impossible to know how many Civil War soldiers suffered from PTSD. There are, however, certain things we do know. While most men were presumably able to compartmentalize their experiences and go on to lead normal lives, others were powerless to cope with the memories and the pain. Then, as now, some of them chose to find peace through suicide. The Union Army reported only 391 suicides during the war, but no records were kept of the number of PTSD victims who took their own lives in the weeks, months, and years after they returned home.

Over time, as America was involved in other wars, PTSD was identified by other names: gas hysteria, shell shock, battle fatigue, combat neurosis, etc. The symptoms, however, remained constant. We need only read the medical records, or study the letters and journals of distraught families of the veterans, or of the soldiers themselves, to know that—whether they wore Union blue or Confederate gray—the soldiers of the 1860s underwent the same personal hell, and suffered the same post-traumatic stress disorder, as those who would serve in the wars to come.

Ron Soodalter, a regular contributor to America’s Civil War, is the author of Hanging Captain Gordon and The Slave Next Door.

Consigned to “a living death”

Post-traumatic stress disorder in the Civil War was no respecter of rank—common soldiers were by no means the only ones who suffered. Senior Civil War leaders, particularly those who consistently “led from the front,” were also victimized by it. One of these, praised by Ulysses S. Grant as the Union Army’s “most promising young officer,” was Ranald S. MacKenzie. Graduating first in his West Point Class of 1862, MacKenzie achieved the rank of major general of volunteers through his daring leadership in some of the war’s fiercest battles, including Second Bull Run, Antietam, Gettysburg, the Overland Campaign, Petersburg, Cedar Creek and Five Forks. He was wounded in six of these battles, tributes not only to his aggressive style of command, but also starkly indicative of the intense combat he endured throughout his Civil War service.

Yet, the PTSD symptoms that afflicted MacKenzie (and which, in fact, would contribute to his death at the age of only 48) did not first appear until years after the war. Indeed, MacKenzie’s greatest fame came after the Civil War as, arguably, the U.S. Frontier Army’s most successful Indian fighter. For a dozen years, 1871-83, from Texas to Arizona, Wyoming to Mexico, and points in between, MacKenzie was sent wherever Indian troubles required an experienced, “can-do” commander to rescue the situation. In the process, MacKenzie suffered a seventh combat wound—a Comanche arrow in his thigh in 1871.

But by 1883, a year after his promotion to Regular Army brigadier general, 12 years of arduous frontier service, closely following his Civil War ordeals, had left MacKenzie physically and emotionally exhausted. One of his subordinates described MacKenzie as continuously “irritable, irascible, exacting, sometimes erratic, and frequently explosive.” In fact, MacKenzie had already suffered a nervous breakdown in 1881 and his seven combat wounds continued to torment him. His behavior became increasingly erratic—extreme emotional highs and lows, unprovoked violent outbursts, estrangement from others, feelings of persecution. Despite some lucid periods, MacKenzie’s obviously severe PTSD symptoms finally forced his superiors into action.

In December 1883, MacKenzie was escorted to the Bloomingdale Asylum for the Insane in New York City and diagnosed with “paralysis of the insane” (a neuropsychiatric disorder also known as paralytic dementia). On March 24, 1884, he was medically retired from the Army, and in June was released to his relatives’ care. MacKenzie died at his sister’s home on Staten Island, N.Y., on January 19, 1889, less than five months after his 48th birthday. The Army and Navy Journal noted the passing of “the once brilliant” officer and lamented “the cloud which overshadowed his later years and consigned him to a living death.”

Perhaps the most fitting tribute to MacKenzie’s memory is the Sheridan Veterans’ Affairs Medical Center in northern Wyoming. Located on the former Army post Fort Ranald S. MacKenzie (established 1898), the center specializes in treating veterans for psychological issues, particularly PTSD. –Jerry Morelock