Germany invaded Belgium on Aug. 4, 1914, prompting the British government to dispatch an ultimatum to Berlin demanding the immediate withdrawal of German forces, stating that a failure to do so would result in war with the British empire. No such withdrawal was forthcoming, and by day’s end the general European conflict that had been brewing since the June 28 assassination of Austro-Hungarian heir apparent Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo was officially on.

‘I can’t turn away now,’ Troubridge insisted. “Think of my pride’

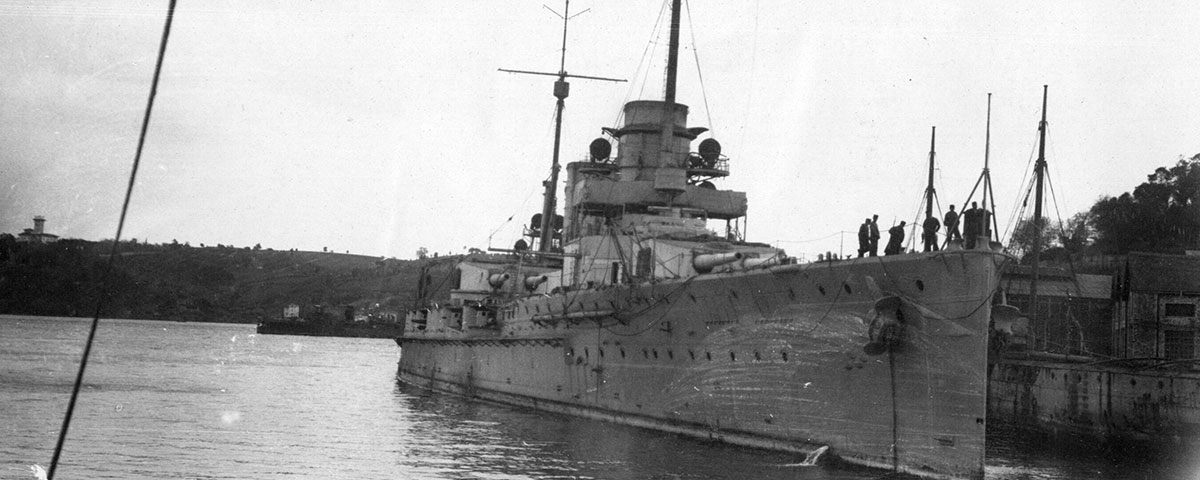

Though not unexpected, the outbreak of war caught many prospective participants flat-footed. Among them were the captain and crew of the Imperial German Navy battlecruiser Goeben, which was cruising the Mediterranean with the accompanying light cruiser Breslau. Though warships of Britain’s Royal Navy dominated that body of water, Goeben—a fast, heavily armed and relatively new vessel—was the most formidable surface combatant between the Strait of Gibraltar and the coast of Ottoman-controlled Palestine. With the declaration of war the Royal Navy’s powerful Mediterranean Fleet knew it must sink or neutralize the German ship.

Only days earlier, on July 30, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill had warned Admiral Sir Berkeley Milne, commander in chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, of the danger posed by Goeben:

Your first task should be to aid the French in the transportation of their African army by covering and, if possible, bringing to action individual fast German ships, particularly Goeben, which may interfere with that transportation.…Except in combination with the French as part of a general battle, do not at this stage be brought to action against superior forces.

Though Goeben’s captain, Rear Adm. Wilhelm Souchon, was unaware of Churchill’s interest in his ship, he rightly assumed the British would do everything in their power to take out the battlecruiser. Informed by his own high command that no help would be forthcoming in the Mediterranean from their Austro-Hungarian ally, Souchon decided to make for the Ottoman port of Constantinople (present-day Istanbul). His plan, he wrote, was to “force the Turks, even against their will, to spread the war to the Black Sea against their ancient enemy, Russia.”

Just before midnight on Aug. 6, 1914, 52-year-old Rear Adm. Ernest Troubridge received information regarding Goeben’s position and presumed course. The British light cruiser Gloucester, guarding the southern Strait of Messina, had reported Goeben’s departure from Messina and was shadowing the battlecruiser. The commander of the Mediterranean Fleet’s 1st Cruiser Squadron, then guarding the entrance to the Adriatic Sea, made some quick calculations and determined he could intercept the fleeing German battlecruiser off the west coast of Greece. He ordered his flotilla of eight destroyers and four armored cruisers—his flagship Defence, Warrior, Black Prince and Duke of Edinburgh—to shape a course he hoped would allow his vessels to intercept the German ships before 6 a.m. He also signaled the light cruiser Dublin and two destroyers, then steaming north from Malta, to head off Goeben. Knowing that the 9.2-inch guns aboard his cruisers were inferior in range to Goeben’s 11-inch guns, Troubridge intended to find the German battlecruiser and its escort by dawn, hoping the half-light would hamper the enemy gunners’ vision enough to offset their weapons’ superiority.

It was a reasonable plan, but then Troubridge had a change of heart that has been a source of controversy ever since. In the early morning hours of August 7 the admiral discussed his proposed course of action with Captain Fawcet Wray, commander of Defence.

“I do not like it, sir,” Wray said.

“Neither do I,” Troubridge responded. “But why?”

“I do not see what you can do, sir,” Wray replied. He then argued what Troubridge already knew, that the faster Goeben could circle around the Royal Navy cruisers, pounding the British vessels while remaining beyond the range of their guns.

Troubridge then asked the flagship’s navigator whether Defence could actually come within range of Goeben before dawn. The navigator did not think so.

“I can’t turn away now,” Troubridge insisted to Wray. “Think of my pride.”

“Has your pride got anything to do with this, sir?” the officer countered. “It is your country’s welfare which is at stake.”

Troubridge thought this over and shortly before 4 a.m. gave the order to break off the pursuit of Goeben. The admiral then signaled to Milne: “Being only able to meet Goeben outside of the range of our guns and inside his, I have abandoned the chase with my squadron. Request instructions for light cruisers. Goeben evidently going to eastern Mediterranean. I had hoped to have met her before daylight.” Milne could have ordered Troubridge to engage the German ships no matter the odds. As it was, the senior officer did not respond for some six hours, by which time Troubridge had withdrawn his flotilla to Zante to refuel, and Goeben was far out of reach.

Troubridge’s supposition that his quarry was headed to the eastern Mediterranean was only partially correct. The German battlecruiser did initially steam east—Gloucester giving chase to Cape Matapan—but then turned north into the Aegean Sea. After coaling off the island of Donoussa, Goeben made for the Dardanelles, which it reached on August 10. Six days later, in a clever subterfuge to skirt neutrality rules, Goeben and Breslau were reflagged as the “Ottoman” warships Yavuz Sultan Selim and Midilli, though they remained crewed by German sailors. The Turks appointed Souchon commander in chief of the Ottoman navy, and on October 29 he attacked Russian naval bases in the Black Sea. The raid by nominally Turkish ships precipitated a declaration of war by Russia against the Ottoman empire on November 2, with Britain and France doing the same three days later. Souchon had fulfilled his promise to force Turkey into the war as an ally of Germany.

The reflagging of Goeben and Breslau as Turkish vessels was a major embarrassment for Britain. The German warships had not been chased out of the Mediterranean and interned by the Turks, as the Royal Navy had at first claimed. In fact, the Turks had welcomed the two ships into service as recompense for two Ottoman dreadnoughts under construction in Britain that Churchill had requisitioned into the Royal Navy at the start of the war.

In Britain the political fallout over Goeben’s escape was swift. On August 18 the Admiralty recalled Milne from command of the Mediterranean Fleet and retired him. Troubridge, who believed the German warship had represented the “superior forces” Churchill had cited, received nothing but scorn from the first lord. Churchill later insisted in his memoir of the war The World Crisis that the forces Milne and his subordinate had been instructed to avoid meant “the Austrian fleet, against whose battleships it was not desirable that our three battlecruisers should be engaged without battleship support.”

Churchill was not the only one to call Troubridge’s actions into question. When the admiral returned to Britain in September 1914, he was called before a court of inquiry, which ultimately found he had had “a very fair chance of at least delaying Goeben by materially damaging her.” The matter then passed to a court-martial, which charged the admiral had “from negligence or through other default, forbear to pursue the chase of His Imperial German Majesty’s Ship Goeben.”

But Troubridge had no intention of becoming a scapegoat. He was a sailor of sterling record and reputation, with the credentials to back it up. He had made captain in 1901, had served as naval attaché in Japan during that country’s war with Russia (1904–05), was promoted to commodore in 1908 and in 1912 had been appointed chief of the Admiralty War Staff. He was well-regarded by both superiors and subordinates and had even been tapped to eventually succeed Milne as Mediterranean Fleet commander.

Troubridge was thus no mediocre officer but one of the Royal Navy’s foremost admirals. As such, he vigorously and expertly defended himself during his court-martial, which began on November 5 in Portsmouth aboard the battleship HMS Bulwark. The admiral first noted his instructions not to engage a superior force. Troubridge then pointed out that his ships were plainly unequal to Goeben in both firepower and speed—the guns of his armored cruisers had never registered hits beyond 8,000 yards, and his ships’ top speed was only 17 knots compared to the battlecruiser’s 27. “All I could gain,” he told the court, “would be the reputation of having attempted something which, though predestined to be ineffective, would be indicative of the boldness of our spirit. I felt that more than that was expected of an admiral entrusted by Their Lordships with great responsibilities.”

Called to testify, former Mediterranean Fleet commander Milne said he had expected Troubridge to intercept Goeben on August 7 at 5 a.m. Under cross-examination, however, he admitted sharing with the admiral Churchill’s orders to avoid engagement with a superior force. Wray, captain of Defence, again supported Troubridge’s decision saying, “For four ships to try to attack [Goeben] is first of all impossible because you could not get…[within] 16,000 yards unless she wanted you to, but if you did get within 16,000—or 20,000 yards if you like—it [would be] suicidal.”

The testimony of Commander W.F. French further aided Troubridge. The gunnery expert noted the wide gap in the effective ranges of Goeben’s guns and those of the British ships—some 4,000 yards in favor of the German battlecruiser. Within an hour of engaging the squadron, he claimed, Goeben could have hit all four armored cruisers while easily remaining beyond the reach of their guns.

After four days of testimony the members of the court went into a brief deliberation, then rendered their verdict: not guilty. The panel of senior officers found Troubridge “justified in considering the Goeben was a superior force to the 1st Cruiser Squadron at the time they would have met, viz., 6 a.m. on 7th August in full daylight on the open sea.” To the irritation of Churchill and others at the Admiralty, Troubridge left the court-martial a vindicated man.

Despite Troubridge’s acquittal, the question must be asked: Was he correct in avoiding combat with the battlecruiser?

Beyond doubt Defence, Warrior, Black Prince and Duke of Edinburgh were individually no match for Goeben. The armored cruisers were older and smaller, lagged technologically and carried lighter armament. It was this presumed inferiority that prompted Troubridge to avoid battle with the German battlecruiser, thus allowing it to escape through the Aegean and serve in the Ottoman fleet. But since Goeben’s fighting power was never tested in comparable ship-to-ship combat, we must look elsewhere if we are to determine whether British armored cruisers were really so inferior and German battlecruisers so fearsome.

The World War I performance of battlecruisers was at best equivocal. An examination of the vessels’ intended use can help clarify why this was so. As first sea lord of the Admiralty in 1904 Admiral of the Fleet Sir John Fisher was the driving force behind both the dreadnought-style battleship and the battlecruiser. The latter were meant to scout on behalf of the battle fleet. Fisher also intended that battlecruisers—swift, long-ranged, equipped with radios and armed with battleship-caliber guns—were to hunt down and sink virtually any enemy ships they might encounter. But Fisher never intended battlecruisers should fight battleships.

Britain’s battlecruisers initially performed as planned following the outbreak of World War I. On Dec. 8, 1914, off the Falkland Islands, Invincible and Inflexible used their speed and longer-range guns to destroy the German armored cruisers Gneisenau and Scharnhorst from afar—precisely what Troubridge feared Goeben would have done to his ships.

Then came the Battle of Jutland, on May 31, 1916, in which the Royal Navy lost three of the nine battlecruisers that took part. Indefatigable broke in half and sank after numerous hits by the German battlecruiser Von der Tann. Queen Mary absorbed a salvo from the battlecruisers Derfflinger and Seydlitz before exploding, as one British officer described it, “like a puffball or one of those toadstool things when one squeezes it.” Invincible was lost when shells fired by Lützow and Derfflinger penetrated its midships turret and detonated its magazines.

To add insult to injury the battlecruisers weren’t the Royal Navy’s only casualties at Jutland. The four armored cruisers that had comprised Troubridge’s flotilla in the Goeben chase—the flagship Defence, Warrior, Black Prince and Duke of Edinburgh—joined battle as the 1st Cruiser Squadron under Rear Adm. Sir Robert Arbuthnot. In the midst of the action Arbuthnot noted that the German light cruiser Wiesbaden was badly damaged and, without permission, ordered Defence and Warrior to attack. But before the British warships could close with the crippled cruiser, German battlecruisers and battleships sailed into range. Defence had no chance. Struck by numerous heavy shells, it disintegrated in an explosion so massive that when the smoke dissipated, there was no sign of the ship. Arbuthnot, his flagship and its 900-strong crew were gone in an instant. Warrior was also hit hard and eventually sank. Just after midnight Black Prince stumbled into a group of German battleships in the darkness and was hit by 15 heavy shells. Like Defence, the cruiser disappeared in a massive explosion. That three of the four British warships that took part in the 1914 hunt for Goeben were sunk at Jutland by German guns equivalent to those carried by the escaped battlecruiser validates to some degree Troubridge’s decision to break off pursuit. Indeed, the admiral’s action almost certainly saved his ships and men from watery graves in August 1914.

Acquitted at his court-martial and further vindicated by the events at Jutland, Ernest Troubridge remained in the Royal Navy through the remainder of World War I. He went on to serve in various staff positions but never again held a seagoing command. Ultimately promoted to full admiral, Troubridge retired from the Royal Navy in 1924 and died two years later. Sadly, despite his achievements, he is too often remembered only as “the man who let Goeben escape.”

Marc G. DeSantis is a historian and attorney who has written extensively on military historical subjects for such publications as MHQ, Ancient Warfare, Military History and Military Heritage. For further reading DeSantis recommends The Price of Admiralty, by John Keegan, as well as Dreadnought and Castles of Steel, both by Robert K. Massie.