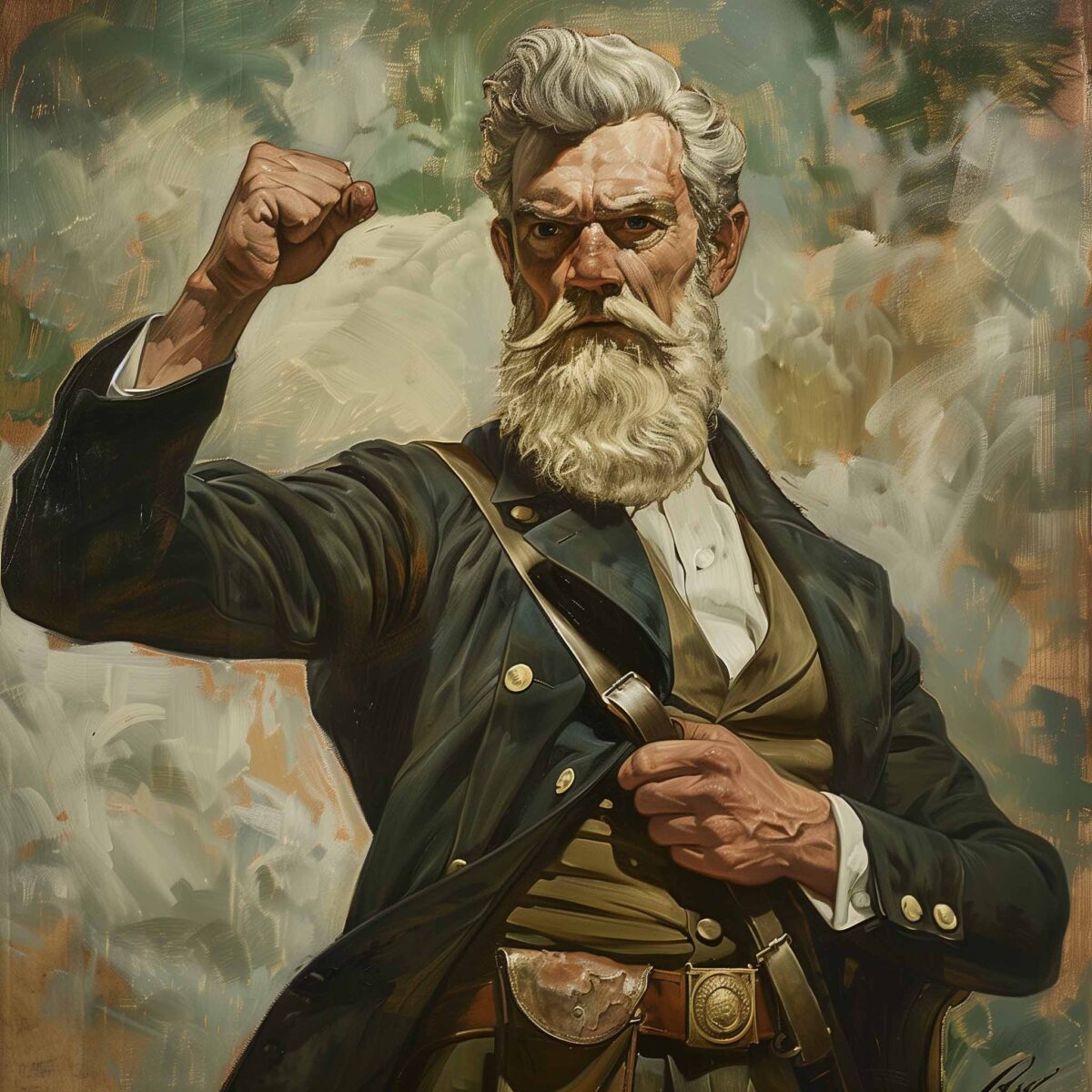

Old John Brown’s failed attempt to launch a “war” against slavery ended just after dawn on October 18 in a bloody rout on the grounds of the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown himself was wounded when a squad of Marines picked from a force of 86 sent by President James Buchanan—all the force he could muster despite widening panic over the rumored slave uprising—overwhelmed the remnant of Brown’s tiny force at dawn on the second day of the “invasion.”

After a six-day trial, a Virginia court convicted Brown of three capital offenses—murder, treason and conspiracy to incite a slave uprising. Judge Richard Parker sentenced him to hang 30 days later.

Brown’s raid sent shock waves through the nation and found few outright apologists. Nonresistant abolitionists praised Brown’s ends, but many of them deplored his means. The raid reverberated throughout the political season. The 1860 platform of the Republican Party officially “denounced the lawless invasion of armed forces of the soil of any State or Territory, no matter under what pretext….” Listed among the causes of South Carolina’s secession from the Union in December 1860 was the refusal of the states of Ohio and Iowa to “surrender to justice fugitives” from Brown’s raid, who were “charged with murder, and with inciting servile insurrection in the State of Virginia.”

At his sentencing, Brown reaffirmed his commitment to his cause and accepted his sentence with memorable words. “Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments,” Brown told the court, “I say, let it be done.” While awaiting the date of what Brown insisted in widely published letters to friends in the North was to be his “public murder,” he pleaded eloquently—not for himself but for the slaves. He insisted that he was “worth inconceivably more to hang than for any other purpose.” In thus embracing martyrdom, Brown himself became a cause among reformers and intellectuals in the North.

Southerners, on the other hand, were convinced that if Brown’s raid had succeeded, the slaves he incited to rebel would have slain their masters. Worse, Brown’s captured correspondence seemed to prove he had the confidential support of influential Northerners. Widespread popular protests in the North on the day of his execution infuriated Southerners such as Virginia Governor Henry Wise, who admired Brown’s courage and forthrightness but condemned “those who sent him.” Despite appeals for clemency, Wise staunchly refused to commute Brown’s sentence.

Southern partisans carried their hatred of Brown to the grave. Six years after Harpers Ferry, as John Wilkes Booth fled authorities following his assassination of Abraham Lincoln, he remembered witnessing Brown’s hanging. “I looked at the traitor and terroriser,” Booth wrote to a friend, “with unlimited, undeniable contempt.” If abolitionists praised Brown’s compassion for the “poor slave,” to white Southerners he was anarchy incarnate.

Despite Brown’s undeniable impact on American history, Brown scholarship has progressed sporadically, and he has inspired only about two dozen scholarly biographies in the 150 years since his capture at Harpers Ferry. Questions about Brown’s readiness to use violence, the roots of his “fanaticism” and his sanity have plagued researchers. The belief that Brown suffered from mental illness distances us from him.

Indeed, as Brown himself understood, the claim that he was “insane” threatened the very meaning of his life. Thus at his trial he emphatically rejected an insanity plea to spare him from the hangman. When an Akron newspaperman telegraphed Brown’s court-appointed attorneys in Richmond that insanity was prevalent in Brown’s maternal family, Brown declared in court that he was “perfectly unconscious of insanity” in himself.

As Brown understood it, the “greatest and principal object” of his life—his quest to destroy slavery—would be seen as delusional if he were declared insane. The sacrifices he and his supporters had made would count for nothing. The deaths of his men and the bereavement of his wife would be doubly tragic and the attack on Harpers Ferry robbed of heroism, its purpose discredited.

In letters to his wife and children, Brown acknowledged that his raid had ended in a “calamity” or a “seeming disaster.” But he urged them all to have faith and to feel no shame over his impending fate.

While his half brother Jeremiah helped gather affidavits supposedly attesting to Brown’s “monomania,” or-single minded fixation on eradicating slavery, John’s brother Frederick went on a lecture tour in his support. Neither Jeremiah nor anyone else in John Brown’s large family renounced the raid.

When it comes to Brown’s war against slavery, the question of his mental balance must nevertheless be addressed. By the time of the Harpers Ferry raid, some of his contemporaries had already begun to question his sanity. As they insisted, was not the raid itself evidence of an “unhinged” mind? Wasn’t Brown “crazy” to suppose he could overthrow American slavery by commencing a movement on so grand a scale with just 21 active fighters?

No one can doubt that Brown sought to elevate the status of African Americans. Throughout his adult life, he conceived projects to help them gain entry into the privileged world of whites. As a youth he helped fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad; as a prospering farmer and town builder, he proposed adopting black children and founding schools for them. In 1849 he moved his family to North Elba, N.Y., to teach fugitives how to maintain a farm.

He held a two-day convention in Canada to secure the participation of fugitive American blacks in his planned war on slavery. He wrote a declaration of independence on their behalf. He respected and raised money for “General” Harriet Tubman and called his friend Frederick Douglass “the first great national Negro leader.” Yet to the extent that in his projects he envisioned himself as a mentor, leader or commander in chief, Brown’s embrace of egalitarianism was, paradoxically, paternalistic. He solicited support from blacks for the war against slavery but not their counsel in shaping it.

Despite that, his black allies never called seizing Harpers Ferry crazy. Although Brown had been hanged for his actions, Douglass insisted the raid had lit the fire that consumed slavery. Brown chose to open his war against slavery at Harpers Ferry, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in 1909, because the capture of a U.S. arsenal would create a “dramatic climax to the inception of his plan” and because it was the “safest natural entrance to the Great Black Way” through the mountains from slavery to freedom in the North.

Harpers Ferry wasn’t Brown’s first foray onto the national stage. In 1857 his band of men had killed several proslavery settlers in “Bleeding Kansas,” hacking to death five men along Pottawatomie Creek with short, heavy swords. Scholars differ on whether the killings should be considered murders or acts of war following the proslavery sack of Lawrence just days before. I have found evidence that Brown and his sons saw their attack as a kind of preemptive strike against men who had threatened violence against freestaters. But to understand is not necessarily to justify or excuse. How a deeply religious man could commit such an act is a question one cannot ignore in assessing Brown’s mind.

Du Bois understood that Brown’s recourse to violence in killing “border ruffians” in Kansas and his attempt to seize the armory at Harpers Ferry in order to arm slaves had caused “bitter debate as to how far force and violence can bring peace and good will.”

But Du Bois, a co-founder of the NAACP, did not think slavery could have been ended without the Civil War. He concluded that “the violence which John Brown led made Kansas a free state” and his plan to put arms in the hands of slaves hastened the end of slavery. Du Bois’ book John Brown was a “tribute to the man who of all Americans has perhaps come nearest to touching the real souls of black folk.” African-American historians, artists and activists have long eulogized Brown as an archetype of self-sacrifice. “If you are for me and my problems,” Malcolm X declared in 1965, “then you have to be willing to do as old John Brown did.”

Blacks’ reverence for the memory of Brown has not inspired those mainstream historians uncomfortable with Brown’s reliance on violence. The belief that he may have suffered from a degree of “madness” has echoed down through the decades in Brown biographical literature. In his popular 1959 narrative The Road to Harpers Ferry, J.C. Furnas argued that Brown was consumed by a widespread “Spartacus complex.”

But Furnas also found that “certain details of Old Brown’s career” and writings evidenced psychiatric illness. Brown might have been “intermittently ‘insane’…for years before Harpers Ferry,” Furnas specu- lated, “sometimes able to cope with practicalities but eventually betrayed by his strange inconsistencies leading up to and during the raid—his disease then progressing into the egocentric exaltation that so edified millions between his capture and death.”

Careful historians like David M. Potter reaffirmed the centrality of the slavery issue in his posthumously published synthesis The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, but even Potter conceded that Brown “was not a well-adjusted man”—despite the fact many abolitionists shared his belief that the slaves were restive.

In 1970 historian Stephen B. Oates sought to bridge the rival biographical traditions by depicting Brown as a religious obsessive in an era of intense political conflict. Oates’ Brown was not the Cromwellian warrior of early legend builders. Nor was he the greedy, self-deluded soldier of fortune of debunkers.

He was a curious, somewhat schizoid amalgam of the legend builders’ martyr and his evil doppelganger. This Brown possessed courage, energy, compassion and indomitable faith in his call to free the slaves. He was also egotistical, inept, cruel, intolerant and self-righteous, “always exhibit[ing] a puritanical obsession with the wrongs of others.”

Oates was doubtful that historians might ever persuasively identify psychosis in a subject they studied. He repudiated historian Allan Nevins’ belief that Brown suffered from “reasoning insanity” and “ambitious paranoia,” but he declared that Brown was not “normal,” “well adjusted” or “sane” either (later dismissing these terms as meaningless).

But reference to Brown’s “glittering eye”—a telltale mark of insanity in 19th-century popular culture—invited Oates’ readers to conclude that Brown was touched with madness after all. Finding in Brown an “angry, messianic mind,” Oates straddled the two biographical traditions. For three decades, his portrait of Brown has perpetuated the image of mental instability.

To get to the roots of Brown’s mental state, we must turn to those closest to him for help. Analysis of the scores of letters written by members of both Brown’s immediate family and the extended family he referred to as the “connection” reveal a John Brown quite different from the self-absorbed, humorless, rigid, imperious, driven fanatic portrayed by some biographers.

Letters Brown exchanged with his father, his wife and his dependent and grown children over several decades reveal a warmer, more engaged father than heretofore pictured. Although he moved his family frequently, he was not a “wanderer” or a “loner.” Brown and his father, “Squire” Owen, remained fast friends despite the latter’s exacting standards of piety and worldly success for his eldest son. Owen’s home in Hudson, Ohio, remained a vital part of his son’s emotional universe to the end.

John Brown asked forgiveness of his wife for his long absences while driving cattle to market or selling prize sheep, and he often complained of homesickness. He loved to hold his children and sing to them; he regularly brought the little ones presents, and he often teased his adolescent sons about their preoccupation with girls.

In 1846 Brown met the tragic death of daughter Amelia—“little Kitty”—and the loss of other children soon after, despite his own grief, with words of encouragement and reaffirmations of faith in a compassionate God to his bereaved second wife, Mary Ann, who bore him 13 offspring. Indeed, he was resilient in the face of God’s “afflictive Providences” and was apparently seldom “blue” for long periods. The only time in his adult life of which we have any record when he was genuinely depressed for months or even weeks was while mourning the death of his beloved first wife, Dianthe, in 1832.

A Calvinist who believed that earthly life was a time of testing and trial, Brown accepted reversals with courage and renewed hope. Even after the failure of speculative enterprises he entered into with his father or his neighbors, Brown was resilient. After a variety of disappointments, Brown faced starting over in collaboration with his adult sons with fortitude and optimism.

Although he later despaired of his sons’ religious apostasy, Brown defended his faith in the Bible and his belief in “the God of my fathers” to them and also to his teenage daughter, Annie. The dissenters all remained close to their father despite their rejection of his biblical Christianity.

Even though he preached serious-mindedness, Brown’s temperament was neither solitary nor morose. His habits were not rigid, and he adapted easily to conditions in the field. Brown clearly possessed a sense of humor; in fact, he once tried to win the open support of the Rev. Theodore Parker by writing to him in a comic Irish brogue!

Brown’s medical history explains much that has been mistaken for mental illness in his record. Like others in his family, Brown suffered from repeated bouts with “fever and ague”—malaria—and was often bedridden during his last years. Yet even when he had to travel prone in the bed of a wagon, his energy drained by the illness, he never despaired of his project.

The “terrible gathering in my head” of which he complained for several weeks, and which some writers have mistaken as evidence of mental illness, proves to have been a prolonged infection in his sinuses and ear.

Even after staying awake two nights in succession during the raid, Brown was able to respond for more than an hour to questions from authorities. With Senator Mason and Governor Wise leading this questioning, he knew his raid had not altogether failed to win an audience. He also managed to fashion brief speeches for the assembled correspondents.

His apparent elation at his questioning was due in part to their presence; he knew he would reach readers of the “penny dailies” who were sympathetic to the cause. His war on slavery had long been in part a propaganda campaign in what were called the “prints.”

But what about the record of mental illness in Brown’s family? A number of John Brown’s maternal relations were at times committed to mental asylums, but we do not know what illnesses they may have suffered from. The youngest son of Brown’s first marriage, Frederick, began in his late teens to suffer frequent episodes of a mood disorder sufficiently severe that his father took him to a “celebrated” physician for treatment; Frederick was never institutionalized, but the family kept him indoors when his “spells” became severe.

Brown’s eldest son, John Jr., suffered a psychotic episode in Kansas. He too did not receive treatment, and for more than a year his illness resulted in symptoms like those we associate today with post-traumatic stress disorder. John Jr. later attributed the episode to the strain of losing command of his militia company after the Pottawatomie killings, in which he had no hand, and to his being arrested and held in chains for “treason” by the territorial authorities as a free-state legislator. John Jr. went on to fight in the Union Army during the war.

We also know that late in life, Brown’s eldest daughter, Ruth, experienced major depression that lasted for nearly a decade.

Altogether, these illnesses suggest that perhaps either John or Dianthe carried a hereditary predisposition to affective disorder. Yet before Brown’s Harpers Ferry raid no one in his wide circle of friends and relations ever suggested that he ought to be committed or to commit himself for treatment at a county institution or to seek the help of an “alienist.”

If friends and former associates petitioned the court for commutation of his death sentence after the raid, their affidavits (now located in the Wise Collection at the Library of Congress) show at best a range of “symptoms” far short of modern diagnostic standards for a major psychiatric disorder.

To be sure, Brown became excited when acquaintances in Ohio made light of slavery or suggested that time would eventually eradicate it. He was pledged to destroy slavery, and indifference to it deeply offended him. But at the time when several of the affiants reported such “agitated” incidents, Brown had recently sought them out to raise money for his war against slavery. He was then traveling with heavily armed young “volunteer regulars.”

He had recently left Kansas, where he had fought in a number of skirmishes and won celebrity as a champion of the free-state cause. In that context, much of what the affiants attested lost its punch.

No one ever suggested that Brown’s anger or high-decibel talk went on for long. If Brown suffered from undiagnosed mental illness in that era before the rise of psychiatry, he displayed few signs or symptoms that modern psychiatrists could identify as being linked to mental disorder.

Was it right, then, to carry the “war into Africa”? The men who petitioned the Virginia court to have Brown committed insisted he must be mad to have been raising a force to resume the fighting that had torn up Kansas. To admit otherwise was to concede that for rational people the sin of slavery might be great enough to override lifelong understandings about the rule of law, tolerance for differing opinions, the efficacy of democratic processes and the immorality of killing. If Brown was perfectly sane, conscientious men and women had to consider and perhaps reassess their own values. Was the perpetual bondage of millions of greater importance than the lives of slave owners and their allies?

Harpers Ferry answered that question in the affirmative. Implicitly it presupposed a hierarchy of values that, if widely adopted, would threaten the end of the slave regime. In a sense, then, Brown’s contribution to history was at a minimum to make righteous violence in the name of freeing the slaves thinkable for many who might not otherwise have considered the question.

Thus Brown’s life—and his self-fashioned “martyrdom”—were a rebuke not only to his reluctant contemporaries but also to revisionist historians who deny that antebellum Americans felt the moral urgency of ending slavery sufficiently to kill over it. To “get right” with Old John Brown is to accept righteous violence as intrinsic to our heritage.

Robert E. McGlone, an associate professor of history at the University of Hawaii, has studied John Brown for decades. That research led to his new biography, John Brown’s War Against Slavery, published by Cambridge University Press in July 2009.