At the end of a hot summer day in 1876, Sitting Bull and his nephew, One Bull, left their lodges in a large encampment of Cheyennes and Lakota Sioux, crossed a bordering stream and climbed a hill on the ridge beyond. The Lakota leader sensed that a momentous battle was about to unfold, and in a vision a few weeks earlier he had foreseen a great victory, but he still felt a need to plead for divine protection over his people.

Atop the hill the two men smoked a ceremonial pipe and lay down as offerings a bison robe and tobacco wrapped in buckskin. Then Sitting Bull prayed. It was a “Dreamy Cry,” a call for special favor. “Pity me….Wherever the sun, the moon, the earth, the four points of the wind, there you are always,” he called out to the Great Mystery (Wakantanka). “Father, save the tribe, I beg you….Guard us against all misfortunes or calamities. Pity me.”

The next day, June 25, Lakota and Cheyenne warriors turned an attack by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry into a rout, killing 268 and laying siege to the battered survivors. Among the dead was Custer. He had ordered part of his force to attack from the south, then he had led more than 200 men along high ground to the east to assault the camp from the other end. But as he descended to the river, called the Greasy Grass by the Sioux and the Little Bighorn by whites, hundreds of warriors met him and his troopers, drove them back up the ridge and slew them all.

The end came on an elevation where the dismounted cavalrymen, panicked and choking on dust and rifle smoke, probably never noticed at their feet a bison robe and tiny bundles of tobacco tethered to sticks of cherry wood. Today hundreds of thousands of people walk up that hill each year to visit what is arguably the most famous piece of ground in the long history of America’s Indian Wars. They know it, however, not as the place where Sitting Bull prayed for favor from the Great Mystery but rather as the site of the seeming answer to his prayer: Custer’s last stand.

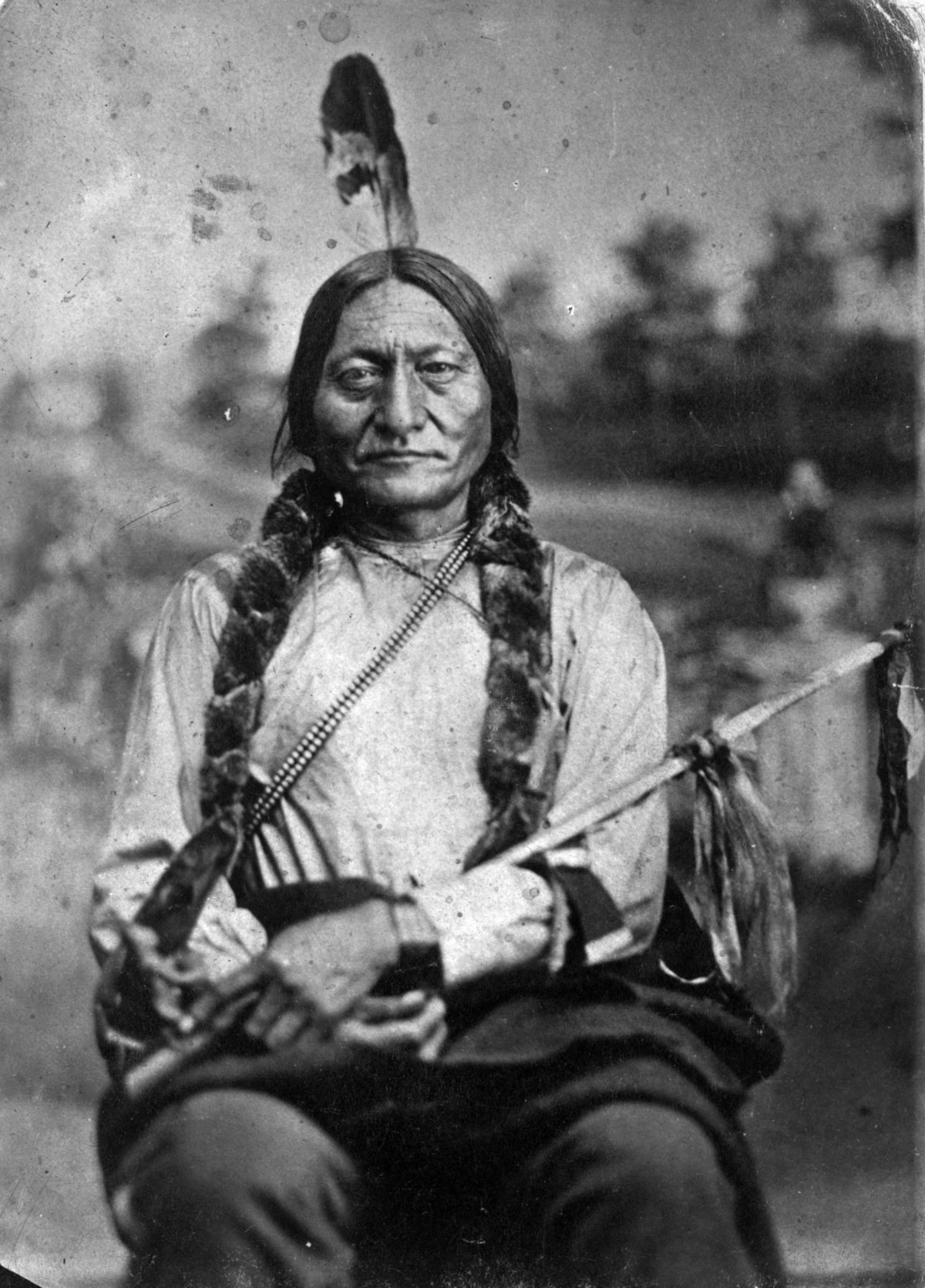

In a way it is fitting that Sitting Bull’s prayer on Custer Hill is so little known. Sitting Bull is one of the most familiar American Indians in our history. He is typically remembered as a great warrior, but among his people he is more renowned as an extraordinarily gifted wichasha wakan, or holy man. Such a person is recognized for unusual abilities to pierce the veil between the seen and unseen, to receive visions of insight and prophecy from the divine, to interpret the dreams of others, to commune with other creatures and the forces at work around him, and generally to gain an intimate relation with Wakantanka, the spirit said to sustain the world and all that is in it, down to the tiniest mote of dust.

Sitting Bull’s leadership arose more from those abilities than from any battlefield exploits, for his people believed that anything of real importance—the outcome of a hunt or battle, turns of the weather, illness or health, the overall quality of life—depended on how well aligned they were with spirits that were everywhere, in all animals and plants as well as in stones, clouds, stars, storms and things whites considered inanimate. All of these spirits in turn were part of Wakantanka. A wichasha wakan’s ability to reach into that spirit world made him a medium to ultimate sources of good and ill, and thus a man more valuable than any warrior.

Sitting Bull was probably born in 1831 along the Grand River in the western part of present-day South Dakota. His father and two uncles were prominent figures among the Hunkpapas, one of seven subgroups of the Lakotas, the westernmost of three Sioux nations. He earned the high regard of his people early, killing his first bison when he was only 10 and mastering the hunt in a few years more. He was a powerful singer and an imitator of birdcalls and was respected for his character. He was nicknamed “Slow” (Hunkesni), which described not his abilities—in fact in his prime he was regarded as the Hunkpapas’ fastest footracer—but his quiet, deliberate and thoughtful approach to dealing with problems. And even before his birth, he said later, the Great Mystery allowed him to see from his mother’s womb. There he began his study of the world, including the smallpox that was chewing at his people: “I was so interested that I turned over on my side.”

He shone most in warfare and spirituality, as revealed in two alternative stories of how he got his more famous name. In one, the 14-year-old Slow pursued one of the Lakotas’ archenemies, a Crow, and unhorsed him with a terrific blow from a tomahawk. Striking an enemy, “counting coup,” brought more honor than killing, and in the ensuing celebration, after Slow received a white eagle feather to signify him as a warrior, his proud father gave his son his own name, Sitting Bull (Tatanka iyotanka), and took a new one for himself, Jumping Bull (Tatanka yotanka).

By the other story, Slow, then only 6, encountered a large bison bull one early morning while tending horses. The bull was leaning back on his haunches. Slow was frightened, but the animal showed no aggression and only looked with a gaze the boy could not break. When the bull finally lowered to a stance and walked away, the boy thanked him for his pity and said, “I respect you.” The incident was taken as an omen both of success in the hunt and a rare bond with other creatures. Slow was renamed Sitting Bull.

Both aspects of his reputation were soon burnished bright. At 15, Sitting Bull counted a second coup and over the next several years fought bravely and often against rival Assiniboins and Crows. In his 20s, he joined the prestigious Kit Fox and Strong Heart warrior societies, and in the latter rose to the high honor of a sash bearer. At 26, he was chosen a war chief of all the Hunkpapas.

Several months earlier, his calling as a wichasha wakan had been confirmed in the Lakotas’ most important ceremony, the sun dance. Held every June, the ritual was less a worship of the sun than a renewal of the people’s bond with Wakantanka and a supplication for favor, protection and support, especially access to the bison that were the mainstay of their economy. Eight days of preparation were followed by four days of dancing and chanting around a tall cottonwood pole that had been carefully chosen and erected just so. Some dancers had slivers of cherry wood inserted under the skin of their chests or backs and tied to bison skulls or to the pole. The terrible pain as they danced, staring into the sun, hour after hour, was an offering and sacrifice made in hopes of a vision, a moment of clarity about their lives and that of the Lakotas.

In the 1856 sun dance along the Little Missouri River, Sitting Bull made the ultimate commitment, pierced front and back and bound to the center pole. After days of pulling against the bonds, staring sunward as he danced and calling out with pleas for bountiful hunts and good health for all Lakotas, a voice finally came to him: “Wakantanka will grant your wish.” A holy man was expected to have such a vision, and so about the time he was recognized as a war chief his spiritual status was affirmed as well.

A sun dance touched on the essence of what it meant to be a wichasha wakan—and of the meaning of power itself. Power was alive everywhere in the world—in animals and plants, the weather and the earth and all else. Power was understood less in white terms, as imposing one’s will on others, than in aligning oneself with the many sources of power all around. As in a sun dance, those powers were to be approached humbly and generously, with gifts and personal sacrifice, and the natural prayerful response was to offer respect and to ask for compassion. “Pity me,” Sitting Bull began his appeal on the hill above the Greasy Grass. And hunters on the Columbia River would sing to their prey: “Pity us, and be driven easily down to the place where we shall shoot you.”

A wichasha wakan was often equated, a bit misleadingly, with a medicine man. The more common designation applied most accurately to someone who could cure, and cause harm, through his conjuring abilities and his understanding of plants and herbs. That was not Sitting Bull’s forte. “Medicine,” however, could also mean “having the power to do things… ordinary men cannot do,” wrote Robert Higheagle, a fellow Lakota, and by that definition, Sitting Bull was “a man medicine seemed to surround someway.”

Cultivating that medicine was a lifetime’s work. Because the Great Spirit took an infinite number of forms, a holy man should study its manifestations, which meant learning from each its essential nature and power, benevolent and otherwise. An otter had to be treated carefully, for instance, never killed from horseback and its meat never eaten. Sitting Bull studied early under his parents and uncle, Four Horns, and discovered an ability to converse with animals. At 15, the year he counted a second coup, he came across a wolf with two arrows in its body. Help me, the animal promised him, and your name will be great. The teenager removed the arrows and washed and dressed the wounds, and from then on a connection to the wolf tribe was secured.

Because animals shared the world’s power with people, reciprocal relations, like Sitting Bull’s with the wolves, made for valuable alliances. He was especially close to birds. While sleeping under a tree as a youth, he dreamed a beautiful bird saved him by warning of an approaching bear, and on waking he saw a woodpecker “looking at him and knocking away.” Spontaneously he made up a song and sang it, ending: “Ye Bird Tribes, from henceforth/always my relation shall be.” As a man he found meadowlarks to be close kin to Lakotas, offering helpful observations and practical advice. Calves’ liver is nutritious, one told him. Teach the young to treat meadowlarks well, he urged friends, so those special allies would always speak our language.

In the 1860s, Sitting Bull’s military star continued its ascent. As the War Between the States raged in the East, he led assaults on white troops who were starting to challenge the Sioux on the Upper Missouri River and in the central Dakotas. Then in his 30s, Sitting Bull rode bareback into a fight, his powerful arms, back and legs brightly painted and his hair pulled back. By about 1866, his reputation was such that other warriors entered a scrap shouting, “TatankaIyotanka he miye!” (“Sitting Bull, I am he!”)

It was not a literal claim. Given his melding of military and spiritual prowess, the belief was that a “mystic or mysterious power” would come into a warrior invoking Sitting Bull’s name. His standing as a wichasha wakan was expressed in other ways. A gifted singer with a powerful voice, he composed many songs. Some were personal, like a tribute to his mother and an encouragement to his favorite horse, the sorrel Bloated Jaw, but the majority honored the sacred, the Lakota equivalent of psalms. One sung at sweat baths was of Wakantanka’s call to his people:

This earth the Creator I am,

Ye Tribes, may you live.

This earth the Creator I am,

Ye Tribes, may you behold it.

And this, meant to be the voice of the sun assuring fair weather during the annual dance honoring him:

With visible countenance I come forth,

Buffalo I have given you [for food].

With visible countenance behold me.

Sitting Bull’s devotions as a wichasha wakan cultivated virtues that ranked above those of the battlefield—generosity, kindness and humility. He often gave the bison he killed to the elderly and to unsuccessful hunters, and he was especially adept at smoothing over disputes with the calm deliberation that had given him the nickname of Slow. Relatives remembered his great fondness for children. At the Little Bighorn, he did not fight but organized protection for them and the women. He composed a lullaby he sang to his children and grandchildren while patting their backs:

Alone, alone, my baby is loved by everyone.

Alone, sweet words my child speaks to everyone

The little owls, little owls even [to] them

Alone, alone, loved by everyone.

He was not good looking, Robert Higheagle remembered, and sometimes was clumsy and awkward, but “there was something in [him] everybody liked.”

Sitting Bull’s piety, cultivated medicine and military prowess steadily fed his stature among the Lakotas, and by the 1870s, as he entered his 40s, it was unsurpassed. He played prominently in several men’s societies, including the Silent Eaters, a secret elite group, never more than 20, that met deep into the night to consider how best to promote the people’s good. As the subgroups of the Lakotas joined increasingly in common cause against whites (wasichus), he emerged as the leading figure of uncompromising resistance by whatever means to any surrender of Lakota independence.

In that role he turned his considerable powers to his people’s good, most obviously, as on the night before Custer’s attack, in prayers of intercession. The previous summer the Lakotas had faced another, equally formidable challenge to their independence: drought. Sitting Bull had received one of the rarest gifts, a dream of a Thunder Bird, the being that rode through the sky and brought lightning and rain, and as a member of Heyoka, the small society of those so blessed, he ascended a hill and, all through the night, chanted a song he had written as words of a Thunder Bird:

Against the wind I’m coming

Peace Pipe I’m seeking, hence

Rain I’m bringing as I’m coming.

And rain came.

During those years he turned to the people’s good a wichasha wakan’s most dramatic use of spirit power: visions. Visions were by no means exclusive to holy men. As among many western Indians, a vision quest was a pivotal event in the life of a young Sioux male. With the help of a spiritual guide he would retire alone to some distant spot and through fasting, chanting and sleep deprivation seek the pity of some spirit. If a spirit appeared—it could be an animal or natural force such as thunder—it would be a protector and helper for the rest of his life. Sitting Bull doubtless had his vision quest, although its result, an intensely personal revelation, is unknown.

A wichasha wakan had a fuller and more frequent access to visions and, most impressively, to occasional views of the future. Sitting Bull’s nephew, One Bull, recalled that as a boy his favorite horse, a pinto Sitting Bull had given him, inexplicably vanished. In a sweat lodge with other holy men, Sitting Bull sought help from a special sacred stone. He learned that a jealous man had stolen the pony and pushed it over the edge of a deep ravine—which is where the dying animal was found.

His most famous vision came not long before the battle on the Greasy Grass. In early June 1876, Sitting Bull called for a sun dance along Rosebud Creek, not far to the east of the Little Bighorn. After purifying himself in a sweat lodge, he sat leaning against the cottonwood pole as others danced around him. Above him hung bison robes as gifts to Wakantanka, but his primary offering was of his own body. Jumping Bull, an Assiniboin he had adopted as a brother and had given his father’s name, worked first on his left arm, then his right, raising the flesh with an awl before slicing off a piece the size of a wheat grain. He took 50 bits of flesh from each arm. Then, as the blood streamed down, Sitting Bull danced for many hours. Finally he fell unconscious.

When roused with cold water, he told his uncle, Black Moon, what he had seen. In the sky, just below the sun, soldiers rode down on an Indian camp, thick as locusts. But these soldiers were upside down, some losing their hats, as if tumbling and falling into the camp. As in his sun dance 20 years before, he heard a voice. Now it said: “I give you these because they have no ears.” The meaning was clear. Horseback bluecoats, heedless of danger, were coming to attack, but Sitting Bull’s people would prevail, and to a man the soldiers would die.

In fact, as Sitting Bull danced, the army was launching a three-pronged assault on the Lakotas. Soon afterward Sioux scouts spotted one column, led by General George Crook, coming from the south, and on June 17, they attacked and fought ferociously, forcing Crook to disengage from the campaign. Barely a week later came Custer’s attack, the one foreseen in the vision. His command, scouting for the second prong under General Alfred Terry, did indeed fall into the Lakota village. Its shattered remnant was found on June 26 by the third column under Colonel John Gibbon.

By some accounts, Sitting Bull’s vision included an instruction that his people should not plunder the bodies of the slain horseback bluecoats—a command they ignored. Perhaps it was retribution, then, that the crushing victory in June was followed by disaster. A humiliated U.S. Army hounded the dispersing Sioux and Cheyenne over the fall and winter. Some of the starving bands, including that of Crazy Horse, surrendered in the spring, but Sitting Bull and several hundred others fled across the border into Canada. The first winter was bitterly cold, with deep snow, and the Lakotas’ deplorable condition worsened even more. Sitting Bull took his last bit of dried venison as an offering, retired to a high place and chanted to the Great Mystery: “Father, pity me….Children with their mothers cry for food….The tribe and myself wish to live. Father, send the buffaloes back to us so we can live and not die.” Soon the weather broke and game returned.

In July 1881, however, official pressure and dwindling bison forced Sitting Bull and his followers to recross the border and turn themselves in. Eventually they were placed on South Dakota’s Standing Rock Reservation. The goal of reservations was to transform Indians into mainstream Americans, an effort that ran to the spiritual—the suppression of native religion and conversion to Christianity. How Sitting Bull responded to Christianity is not clear. Like many Indians, he likely looked to it for sources of power to add to the Lakotas’. By one account he recognized Mary as a human incarnation of a supreme Mother the Sioux venerated. Nothing, however, suggests that he budged on his fundamental beliefs, or that he faltered in using his gifts for his people’s needs.

His beliefs were tested again in 1890 with the arrival of the ghost dance, a religious movement inspired by a Paiute prophet in Nevada. It invoked the old appeals, as in this song from the Arapahos:

Father, have pity on me

I am crying for thirst

All is gone, I have nothing to eat.

Ghost dance practitioners promised that faithful adherence to the new teachings and rituals would prompt the Great Mystery to reverse the terrible losses that had come with Europeans. Many Sioux responded enthusiastically, including those around Sitting Bull near his birthplace along the Grand River. He never took part in the dances, nor apparently gave them his blessing, but neither did he discourage them. Perhaps he saw a chance to shore up his standing, which had sagged among the Hunkpapas since his return from Canada. Probably he probed the ghost dance, as he did Christianity, for possible powers.

The rattled government agent at Standing Rock, however, believed that Sitting Bull was plotting trouble, and in December 1890, he sent Sioux police to arrest him. When he resisted, they shot and killed him. Thus Sitting Bull died, at age 58, at the hands of some of those whose good he had pursued with his considerable gifts, singing to woodpeckers, calling upon lightning and rain, glimpsing what was to come and speaking to sacred stones, calling out in his “Dreamy Cry” to “guard us against all misfortunes or calamities.” The irony was not wholly unexpected. Not long before, Sitting Bull had been walking to his horses in the early morning, as in that naming story when as a young boy he had met the sitting bull and had given him his respect. He heard a voice nearby say, “Dakotas [Sioux] will kill you.” Looking around, he saw who had spoken. It was a meadowlark.

Elliott West, author of several books on Western and American Indian history, is Alumni Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Arkansas.

Originally published in the August 2011 issue of American History.