Conceived to combat Germany’s high-altitude bombers, the Westland Welkin arrived on the scene too late to fulfill its mission

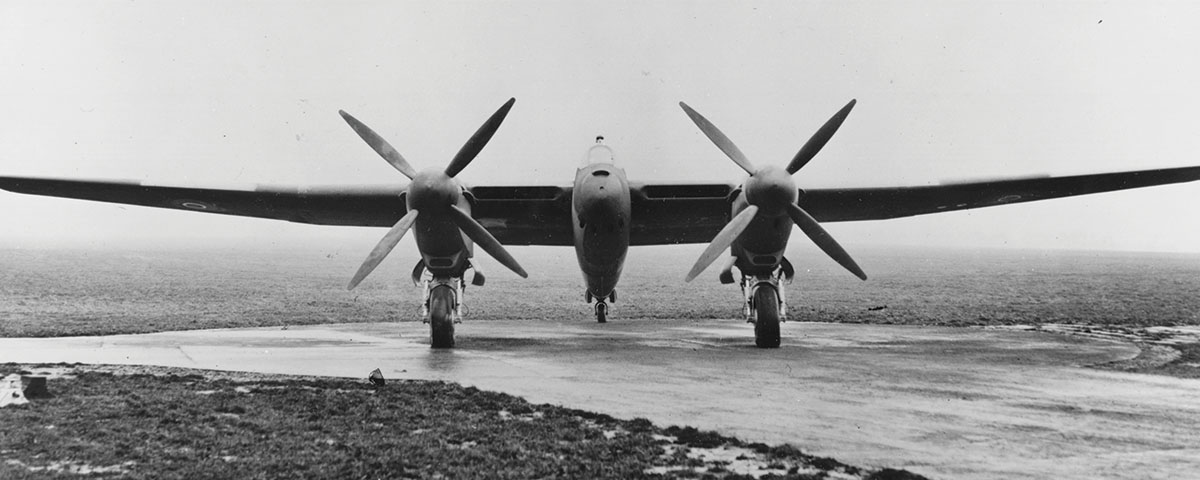

Aircraft don’t come much more extreme looking than the Westland Welkin. With its glider-like high-aspect-ratio wings, big engine nacelles and stubby nose, the Welkin was designed for a highly specialized mission: very-high-altitude interception. Although it proved capable of successfully fulfilling that role for the RAF, the interceptor was built in limited numbers because, by the time it became operational, the threat it was intended to thwart had disappeared.

Prior to World War II, few aircraft were called upon to operate much above 25,000 feet. High-altitude flight subjected aircrews to extreme cold and lack of oxygen, which necessitated heated pressure suits or cabin pressurization. The air was so thin that special wings were required to provide sufficient lift. Internal combustion engines could not run efficiently in the thin air either, unless they were equipped with superchargers to compress the air prior to combining it with fuel in the cylinders. Even the U.S. Army Air Forces’ Boeing B-17 and Consolidated B-24, as well as the pressurized Boeing B-29 that arrived late in the war, seldom ventured much above 30,000 feet. As a result, few fighters existed that were capable of operating above that altitude.

All that changed in 1940, when the Luftwaffe began deploying the Junkers Ju-86P. A radical redesign of an obsolete prewar medium bomber, the Ju-86P featured longer wings, a pressurized cabin and supercharged Junkers Jumo 207 diesel engines. It could operate at altitudes in excess of 39,000 feet, out of the reach of any production fighters of the day. Like the Lockheed U-2 of the 1950s, the Ju-86P could conduct strategic reconnaissance missions over enemy territory with impunity, simply by virtue of its extreme high-altitude performance.

It became obvious to the RAF that if enemy reconnaissance planes could fly higher than its fighters, then high-altitude bombers wouldn’t be far behind. An immediate request went out to the Air Ministry for a fighter capable of reaching altitudes far higher than any previously contemplated. Rolls-Royce responded by developing an improved version of its famous Merlin engine with a two-stage supercharger for better high-altitude performance, while Vickers and Westland began designing specialized fighters to utilize it.

The Vickers 432, which looked a bit like a modified de Havilland Mosquito, ended up losing out to its Westland competitor. Westland’s Welkin resembled its smaller predecessor, the Whirlwind, modified with a longer fuselage, wings and tail surfaces. There was much more to the new fighter than that, though. In place of the Whirlwind’s less-than-satisfactory 885-hp Rolls-Royce Peregrine engines, the Welkin was fitted with a 1,233-hp Merlin 76 and a 77, each equipped with a two-stage supercharger. The most important feature of the new interceptor, however, and the one that took the most time to develop, was its pressurized cockpit. The Welkin had a sealed, bulletproof sliding canopy constructed of a double layer of perspex, with hot air fed between the layers to prevent condensation from interfering with the pilot’s view at high altitude. All control and electrical conduits had to be sealed to maintain cabin pressurization, and the entire cockpit was armored to protect against depressurization in the event of battle damage.

The Welkin was huge for a single-seat fighter, with a length of 41½ feet and a whopping wingspan of 70 feet. By contrast, the Whirlwind was 32 feet long, with a span of only 45 feet. Both fighters were armed with four 20mm cannons, and the Welkin’s top speed of 385 mph wasn’t much higher than its predecessor’s 360 mph. The Whirlwind, however, had a service ceiling of only 31,000 feet, whereas the Welkin could operate at 44,000 feet.

The Welkin made its first flight on November 1, 1942, only two years after it had been ordered, a commendably short time for the development of a new fighter. Like many new aircraft, it had handling problems—some endemic to the design—that needed to be addressed. Not the least of these was its very small flight envelope (flyable speed range) at the lofty altitudes where it typically operated. Due to its long, thick wings, the Welkin was also susceptible to compressibility stall in a high-speed dive.

The war didn’t wait for the Welkin to become fully developed. On August 24, 1942, the Luftwaffe commenced very-high-altitude bombing attacks on Britain with the new Junkers Ju-86R, capable of reaching the then-phenomenal altitude of 45,000 feet. Although each bomber could carry only a single 500-pound bomb at that height, the fact that the new Junkers could operate in British airspace without fear of being shot down gave it a powerful potential impact on morale.

Fortunately for Britain, the RAF hadn’t pinned its hopes entirely on the Welkin. Specially modified Supermarine Spitfire Mark IXs proved capable of reaching the high-flying Junkers, with the first such interception taking place on September 12, 1942. In what would become the highest air combat recorded during WWII, Flying Officer Emanuel Galitzine attacked a Ju-86R at 44,000 feet. Galitzine’s attack was unsuccessful because his left wing-mounted cannon jammed, causing the Spitfire to yaw to the right when he fired the other one, throwing off his aim. But the German crew’s lucky escape worked in the RAF’s favor. Realizing that Spitfires were capable of intercepting its supposedly invulnerable bomber, the Luftwaffe high command reconsidered its feasibility, and the program was discontinued.

By the time the Welkin was ready for production in August 1943, the Ju-86s had been withdrawn, and there simply weren’t any more high-altitude enemy bombers to intercept. As a result only 75 Welkins were completed, and none was issued to an operational squadron. During 1944 Fighter Command flew two Welkins to formulate high-altitude fighter interception tactics—as close as the type ever came to operational service. A two-seat night fighter version, the Welkin Mark II, had also been planned but was scrapped because the de Havilland Mosquito could handle that mission.

It’s perhaps unfair to dismiss the Welkin as a failure. There’s no doubt that Westland’s height-climber was fully capable of fulfilling the highly specialized mission for which it was intended, even though that mission had disappeared by the time it was ready for combat. In addition, the design work that went into the Welkin’s cockpit would pay dividends down the road in the development of pressurized jet fighters.

Originally published in the September 2012 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.