For full article, subscribe to MHQ or purchase MHQ, Spring 2011.

The musketry and artillery fire had died away with nightfall on May 31, 1862. For most of that day, the fighting had raged in the woodlots and clearings around Seven Pines and Fair Oaks Station, several miles outside Richmond, Virginia. The combat’s fury and the bloodletting surpassed anything in the experience of those trapped within it. The day had not gone as planned by the attacking Confederates. Muddy roads and flooded bottomlands from the previous night’s thunderstorms, misunderstood orders, and piecemeal assaults had hampered the Southern operations. Consequently, the error-plagued offensive had not gone forward until early afternoon, hours behind schedule. The attackers had a few successes, overrunning a Union redoubt and wrecking the enemy’s front line. But Federal resistance stiffened, and reinforcements blunted a final Rebel thrust.

Lee sought annihilation on the battlefield, hoping to deliver a killing blow to the enemy

The Confederate commander, General Joseph E. Johnston, rode out from his headquarters late in the day to inspect the terrain and the army’s lines. Johnston had spent the entire morning and most of the afternoon waiting anxiously for word of the attack at Seven Pines. It was not until nearly 3 p.m. that the commander received a dispatch reporting on the action. Now, as he ventured forth to get a firsthand look, a piece of artillery shell struck Johnston in the chest, breaking some ribs. Staff officers secured a litter, and the painfully wounded general was carried to the rear.

Confederate president Jefferson Davis and Brigadier General Robert E. Lee met the litter party. Relations between Davis and Johnston had been strained for months; both men were proud and thin skinned, and they had disagreed over military policy. Davis, however, spoke kindly to the wounded general, expressing hope that Johnston would soon be able to return to duty.

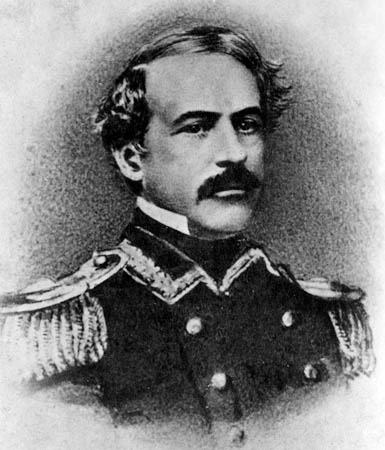

The president started back toward Richmond, accompanied by Lee. Since March, Lee had served as Davis’s military adviser, and the two had developed a mutual trust. At some point, as they rode, Davis asked Lee to assume command of the army. It was to be a temporary assignment. At the time, newspapers called the general “Granny Lee” for his perceived indecisiveness and even timidity. Unlike Johnston, however, Lee had the confidence of Davis. And with a crisis at hand, Davis had no one else.

The magnitude of the crisis extended far beyond the lines at Seven Pines and Fair Oaks. For months, a foreboding shadow had settled across the Confederacy. Defeat had followed defeat—Forts Henry and Donelson, Nashville, Shiloh, New Orleans, and Roanoke Island. Finally, with the Union Army of the Potomac at the outskirts of Richmond, the Confederacy seemed to be a short-lived dream. In words unspoken, Lee had been asked to stay the darkness. Over the next year, he would build an army and craft a strategy of maneuver and aggression that would offer the Confederacy its best hope of victory.

Full article adapted from A Glorious Army, by Jeffry D. Wert. Copyright © 2011. Published by arrangement with Simon & Schuster, Inc.

This post from MHQ Spring 2011 is only a snippet. Please purchase the Spring 2011 issue of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History to read the entire article.