I have never quite decided whether I should consider myself a Vietnam veteran or not. On those occasions when I dress up, I proudly wear a miniature Combat Infantry Badge in my lapel. I did spend 22 months in Vietnam, but the two are not related. It was nearly 30 years earlier, in Burma, that I earned the badge, as a machine gunner with the 475th Infantry Regiment of the Mars Task Force. In Vietnam, I was a CIA officer stationed in Saigon after the war was officially over.

To begin at the beginning, in early 1973 I had been with the agency for 23 years, more than half of that overseas in South Asia, the Middle East and Africa. In 1971, I gave up a branch chief job to attend the Naval War College at Newport, R.I. The class consisted of 100 senior Navy officers and 100 Army, Air Force and Marine officers, along with a dozen civilian intelligence officers from the State Department, the CIA, the Defense Intelligence Agency and the National Security Agency.

When I came back to Langley, I was killing time as a special assistant, waiting impatiently for an appropriate opening in Africa, when I was offered a job in Saigon. I had followed events in Vietnam, but had never considered volunteering. My wife and two children had always accompanied me on previous tours, and I discussed it with them. Unlike the standard military tour of one year in Vietnam, the usual overseas posting for the Foreign Service, the CIA and several other agencies was two years, without any home leave. Vietnam during the war was an exception for civilians: The tour was still two years, but families could not accompany the men, who were at least in theory given a couple of weeks’ leave every six months.

That policy now had been modified. The leave policy for men stayed the same, but wives could accompany their husbands, whereas children could not. Even if the wife accompanied him, the husband was still permitted to visit his children periodically but the wife could not, at least not at government expense. I had assumed that my wife would stay with the children, but she considered that out of the question. The kids were miffed but agreed to share an apartment. We had to promise they could visit, even though it would be at our expense.

My wife and I arrived in Saigon on June 16, 1973. The agency had its own transient facility in Saigon, the Duc Hotel. It had a dining room and a small swimming pool on the roof. A few single people lived there full time, but the primary function was temporary housing for arriving and departing employees, and for employees from the outlying bases coming in for consultation or a bit of R&R and shopping.

Anxious to get out of our tiny room over a busy street, we first accepted a two-bedroom apartment on the third floor of a six-unit building. Unfortunately, the building was located at the intersection of two major thoroughfares, and from 6 a.m. until curfew at midnight the traffic noise was overwhelming. After a couple of months, we moved to a house that was smaller than the apartment and in bad condition, but was located on a cul de sac with a high wall around it. My wife supervised a crew of Vietnamese workmen in the restoration process.

The CIA head office in Vietnam was the “station,” in the embassy building. There were five subordinate “bases” in the appropriate military regions (MRs), now called administrative regions: Da Nang for MR I, Nha Trang for MR II, Bien Hoa for MR III, Can Tho for MR IV and the Saigon base for the Saigon–Gia Dinh district. There were also subbases scattered around the country.

The Saigon base was located behind the embassy in what was called the Norodom Complex. That complex housed the consulate, the military attachés and the Saigon base. It had its own gate, and a Marine guard in a booth controlled access.

I was assigned to the Saigon base. The base had two branches, designated Liaison Operations and Internal Operations. ‘Bill J.,’ the chief of base (COB), wanted me to head up a new external branch focused on a target of opportunity, the Hungarian and Polish members of the International Commission for Control and Supervision (ICCS).

At the time the peace treaty was signed in January 1973, the ICCS was established to monitor the truce, with two Communist delegations and two neutral delegations. When I arrived, the neutral delegations were Iranians and Indonesians. Each delegation consisted of about 200 members, all supposedly military officers and enlisted men.

It seemed like an excellent opportunity to recruit some defectors in place, prepared to report back to the agency after they returned home to Hungary and Poland. We were not looking for outright defections, and in fact refused more than one.

I had five full-time case officers, and we began collecting biographic data immediately. We also began briefing other base, station and State Department officers to act as’spotters’ for us, thus expanding our reach considerably. I also visited the bases at Nha Trang, Da Nang and Bien Hoa to brief the officers there. For some reason I never did get to Can Tho.

One of our better points of informal contact with our targets was on Sundays at the 50-meter, above-ground swimming pool at Tan Son Nhut, which became a gathering place for the ICCS officers. On one occasion at the pool I had a heated argument with a Hungarian major, whom we had already identified as a member of the AVH, equivalent to the Soviet KGB. One of the more absurd claims of Communist propaganda asserted, ‘There are 10,000 U.S. troops at a hidden camp in the Delta, ready to come out and help the ARVN if they get into difficulty.’ When the Hungarian major started spouting that line, I blew up. I said it was no doubt possible for the VC or NVA to impose that kind of discipline on their people, but asked him: Did he seriously think American troops could be so concealed? Would Hungarian troops be able to tolerate the kind of isolation it presupposed? Where were the heavy-lift supply planes? How about swimming pools, commissaries, PXs, etc.? In any case, since the ICCS had freedom to travel anywhere in South Vietnam, why did his delegation not expose this alleged violation of the peace treaty?

I got no answer except sputters, but the general in charge of the Hungarian delegation complained to Tom Polgar, the chief of station (COS), about me. When Tom mentioned it, I told him the story with no apologies. He agreed that the Hungarian deserved it, and we dropped the matter.

Which brings me to a point I should have made earlier. Why would the Hungarians complain to Tom Polgar, who probably everyone in Vietnam knew was the senior CIA man in the country? They just assumed I worked for Polgar, since our cover was paper thin. Oddly enough, no one ever came out and accused us of being CIA. I guess that was the quid pro quo for not pointing out the AVH officers we had identified.

I can sum up my one year in that job by saying that those of us not previously exposed to the Poles discovered how lightly the mantle of communism rested on their shoulders. We had so many volunteers that we had to turn some away and could afford to be selective. The Hungarians were a different matter. We eventually did have some limited success, but I have to say those boys were for the most part dedicated Communists. I have often wondered how they are fitting into the new post-Soviet reality.

All of my previous overseas experience had been as a COB, COS or deputy chief of station (DCOS) — and in each case the office was small, with a couple of case officers and a secretary — so the sheer size of our presence in Vietnam, the largest in the world, took some getting used to. Bases were usually run by a COB, a deputy COB and a chief of operations. With the Saigon base, the third man on the totem pole was the executive officer (XO). At the end of my first year, the man holding that position completed his tour, and Bill J. asked me to take over as XO.

Once the last of our POWs were released in March 1973 and all but 50 U.S. military attachés had been withdrawn, Vietnam became old news. Americans seemed oblivious to the fact that the ARVN lost an average of 1,000 troops per month in skirmishes with the VC in 1973 and 1974. We would occasionally have dinner on the roof of the Caravelle Hotel. From there, you could watch the artillery duels going on out in the countryside.

When our son visited in the summer of 1974, we flew to Nha Trang to go snorkeling. Just as we drove up to the consulate guest house, a half-dozen VC B-40 rockets landed in the town. One of them came down in the street about 50 yards away, leaving a hole a foot deep and 2 feet across. Our son commented mildly that he thought the war was supposed to be over. A friend was stationed at one of the subbases in the Central Highlands, together with a young case officer. One morning the young man went out to fuel up their jeep. The jerrycan he picked up had been booby-trapped with a grenade. There were frequent incidents of that sort.

In December 1974, the NVA made their first serious probe, invading Phuoc Loc province from Cambodia, and by January 7, 1975, they had captured the provincial capital of Phuoc Binh, 100 miles from Saigon. Everyone on our side protested, but nothing else happened.

At about the same time, something occurred that astonished us completely. The embassy had been guarded by a platoon of Marines, under a captain. Now that guard force was reduced to a squad, under a gunnery sergeant.

Next to go, on March 10, was Ban Me Thuot, the capital of Darlac province, in the middle of MR II. The NVA were thus in a position to cut the South in two. Now the NVA tanks came surging down Highway 1, heading for Hue. The 1st Infantry Division, South Vietnam’s best, was well dug in around Hue. President Nguyen Van Thieu panicked and ordered it to retreat to Da Nang. Before the ARVN troops got there, Thieu changed his mind and ordered them back to Hue, but it was too late. They were caught in the open and torn to pieces.

Thieu next ordered a withdrawal from the key Central Highlands city of Pleiku, the headquarters of MR II. The commander was General Pham Van Phu, an incompetent, corrupt and cowardly man who held his position because of his support of President Thieu. Phu withdrew, all right: He loaded his family, even his household furniture, onto helicopters and took off for Nha Trang.

His senior subordinates followed suit. The now-leaderless troops fled in panic down bad roads toward the coast, submerged in a flood of refugees, and were cut to pieces by NVA artillery. There were half a million troops and refugees on this route, and only one in four made it to the coast. General Phu then decamped for Saigon. Just before the fall of the country, he committed suicide.

Since this is my story, I will interrupt this sad tale to explain what I was doing. I was having a really bad feeling about the situation. It seemed to me that the top brass in the embassy were far too sanguine about it. I started to arrange early departure orders for my wife, using the excuse that she wished to rejoin our children in northern Virginia.

Hue fell on March 25, and Da Nang, Vietnam’s second largest city, fell on April 2. The South Vietnamese who escaped always claimed they could have held out if the United States had provided them with more equipment. I have a copy of Stars and Stripes dated April 1, 1975, that lists the equipment abandoned just at Hue and Da Nang: 60 M-48 tanks, 255 armored personnel carriers, 150 105mm howitzers, 60 155mm howitzers, 600 trucks and hundreds of M-16s, machine guns and submachine guns. The total cost of equipment abandoned in MR I and MR II was put at $1 billion and included half the Northrop F-5s, other aircraft and helicopters available to South Vietnam.

In the meantime, my wife’s travel orders had been approved, but by then the embassy was encouraging dependents to leave and was issuing tickets on the spot. She left, protesting, on a Pan American Airways flight on April 3. That evening I received a telephone query: The Air Force was providing a Lockheed C-5A to evacuate as many Vietnamese orphans as possible, and would my wife be willing to act as one of the escorts? Fortunately, she was gone already.

The C-5A took off the next day loaded with 230 orphans plus three dozen American women, mostly Defense Attaché Office secretaries and embassy dependents. Over the South China Sea the rear cargo doors blew open at 23,000 feet, damaging the rear control surfaces. Over the South China Sea the rear cargo doors blew open at 23,000 feet, damaging the rear control surfaces. The pilot headed back for Tan Son Nhut, but had to crash-land before he got there. The plane bellied into a rice paddy, then skipped over a river before coming to a stop. The rescue operation was not helped when ARVN troops, who got there first, spent more time looting than assisting. The death toll was put at 206, including the four American secretaries from the Defense Attach Office next door to the Saigon base. I knew all four of them well.

The next bit of excitement happened on Tuesday, April 8, when a VNAF F-5E fighter-bomber blasted down the street outside our office and dropped two 500-pound bombs in front of the nearby presidential palace. Realizing he had missed, the pilot came around again, which gave me time to get outside for a cautious look at what was going on. He came boring down the street at about 50 feet and dropped his last two 500-pound bombs through the roof of the palace. The pilot’s objective was to kill President Thieu, but his early miss gave Thieu time to reach a bomb shelter.

For 25 years I was under the impression that the pilot was simply fed up with the incompetence of President Thieu. I recently learned that Lieutenant Nguyen Thanh Trung was in fact a North Vietnamese mole who had trained at Kessler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Miss. His orders from the VC were to drop the first two bombs on the palace and the next two on our embassy. The embassy building was pretty sturdy, but the front building of the Saigon base was a prefab, with the structural integrity of a matchbox. At the time we did not know how lucky we were. Trung subsequently led the April 28 raid on Tan Son Nhut by five captured Cessna A-37 Dragonflys (jet trainers converted to light bombers). As of this writing, Trung is a senior pilot with Vietnamese National Airways.

Old hands used to joke about the time General William Westmoreland issued an unclassified order that civilians were not to carry weapons. They felt as if Westy had painted a bull’s-eye on their backs, and the order was pretty widely ignored. During my time in Saigon, most of us did not carry pistols, though I tucked my .38-caliber snub-nosed Smith & Wesson into a belt holster under my bush shirt when I had an agent meeting in some place like Cholon.

The Tet Offensive of 1968 was always hovering in the back of our minds, reinforced by Radio Hanoi referring to a ‘popular uprising.’ As the NVA surged south, we thought about the possibility of a repeat performance. After my wife left, I started carrying the .38 and extra ammo all the time. I had a .45 in my car, an M-2 carbine at home, and more pistols and submachine guns in a safe drawer in the office. Feeling a little embarrassed about this, on the first morning I walked into Bill J.’s office and lifted my shirttail to display the gun. Bill laughed and stood up, pulling a 9mm Browning Hi-Power from his pocket.

Even stranger: I was the main point of contact with the half-dozen Army, Navy and Air Force attachés who worked out of the office across the courtyard from us. The Army attaché came to see me and asked if I could arrange for them to obtain some .45s. They were moving all over the Saigon–Gia Din district to keep on top of the situation, and were uncomfortable without some personal protection. I found it hard to believe, but their main office out at Tan Son Nhut had no weapons to give them. I passed the request up to the COS, who got the ambassador’s permission. Then I took the attachés down the hall to our office of security, where they signed for the required number of .45s and plenty of ammo.

The last two weeks I was there are a bit of a blur, so I will not attempt to put exact dates on what took place. The only battle the ARVN won in the whole wretched affair was 40 miles up the road from Saigon at Xuan Loc. It was a hollow and short-lived victory, as the troops would have been better employed in defending the outskirts of Saigon. They held off the NVA and VC for 10 days, and then the NVA simply bypassed them. Cut off, the ARVN 18th Division plus 3,000 rangers and paratroopers — one-half the strategic reserve for Saigon — were slowly destroyed.

Back at the base, with the approval of the COB, I put out an order that all files were to be either destroyed (shredded and burned) or immediately shipped out to Langley. Every case officer could keep one file folder no more than 1 inch thick for the most essential documents he needed to keep doing his job. There were howls of protest, but I knew most case officers were pack rats, and there were a couple of instances of African stations or bases being overrun during civil wars and the safes left full of classified material. Back in the 1950s, we had thermite grenades on hand in case of such an emergency, but that seemed to have gone out of style. I was determined that if the NVA overran Saigon, they would not find any Saigon base files.

Most of the case officers complied, but on Sunday, April 13, one of them squealed on another one. The guilty party was a police intelligence liaison officer. I opened his safe, and the entire top drawer was full. His files were as well organized as any I had ever seen, but they had to go. I got the man on the phone and told him that if he had not destroyed or shipped them by the next morning I would burn them myself. He did.

When the time came to leave, the Saigon base was swept clean. Unfortunately, the same was not true of other repositories, particularly the embassy. The ambassador would not let his staff clean out their safes, since he was still living in a dream world, hoping that some accommodation could be reached with the Communists. Even more important, the South Vietnamese government’s police and intelligence files were abandoned for the North Vietnamese to find. But that’s another story.

The Saigon base had more than 50 people, and in early April we began to thin out the ranks. Every evening, Bill J., his deputy Monty L. and I would have a meeting and decide who should be sent home next. It was then my job to call them into my office the next day and tell them it was time to go. Of course, most of the secretaries were among the first.

I had a problem with some of the case officers, who came up with all sorts of excuses as to why they could not leave right away. My answer was always pretty much the same: I said I had no faith in the embassy evacuation plan, which called for civilian chartered airplanes out of Tan Son Nhut. I had been at Tan Son Nhut the day an NVA missile shot down a VNAF Douglas AC-47 gunship minutes after it took off, so it seemed to me likely that we would be going out in helicopters, and I did not want one of the case officers to be sitting in my seat. Very few of them could argue with that reasoning, since they felt the same way. They went.

At about the same time, all base and station personnel living in outlying areas were asked to move closer to the embassy. There were a number of small apartments now available that had previously been occupied by secretaries. Another officer and I moved into a two-bedroom, one-bath unit directly across the street from the back gate of the embassy.

I drove my car across the street the next morning and was greeted at the gate by a Marine clad in fatigues and toting an M-16. He stopped me, came to port arms and asked, very formally, ‘Sir, are you carrying any photographic or recording equipment, or any firearms?’ He looked about 15 years old, and I thought if I mentioned my mini-arsenal he might flip out, so I lied. I then asked where he had come from, since I knew all the regulars, at least by sight. It turned out that a full platoon of Marines had flown in the night before from Okinawa. Better late than never.

At this time a lot of the CIA people who had evacuated Da Nang, Nha Trang and other points to the north were gathered in Saigon, and I knew that many of them were carrying M-16s, Swedish K 9mm submachine guns, etc. As soon as I parked, I hotfooted it to our office of security and told them what had happened to me at the gate. The security officer swore, then ran out to find the embassy security officer and get the Marines to stand down.

Finally, on the evening of April 21, the Saigon base was down to 15 people. Bill J. looked at me and said: ‘OK, Dick, it’s your turn. We have too many chiefs and not enough Indians. You leave tomorrow.’

I almost objected, then laughed instead. In response to Bill and Monty’s raised eyebrows, I reminded them of the objections I had been getting for two weeks, and that I had been on the verge of doing the same thing. I said OK, wished them luck and went home to pack my one small suitcase.

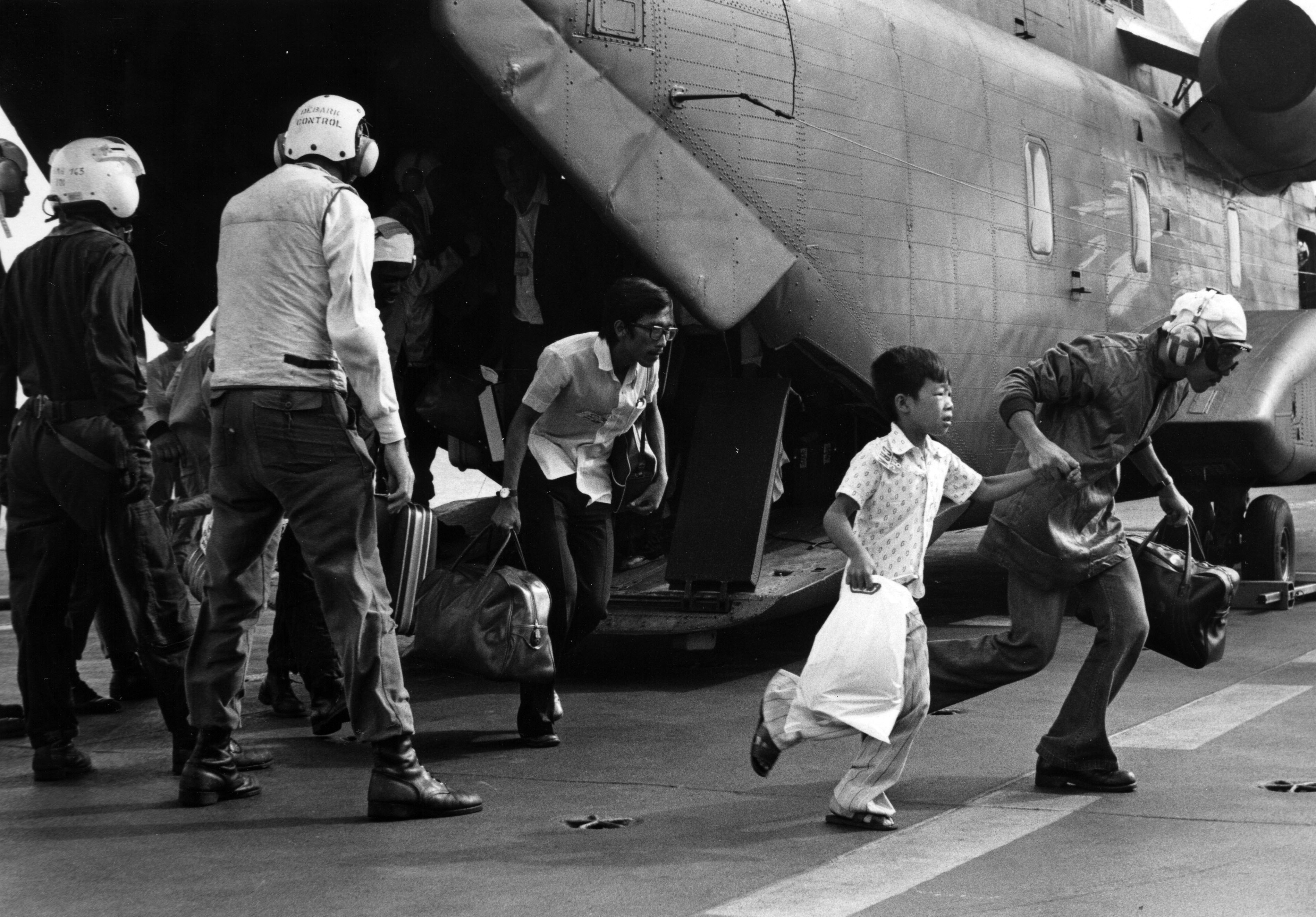

So, despite my harping on the possibility of helicopter evacuation, the next morning one of the last remaining secretaries, a case officer and I were driven out to Tan Son Nhut by the secretary’s husband. We carried our .45s in a brown paper bag, just in case. When we got to the airport we handed the bag to our chauffeur and wished him luck. The three of us then caught the last China Airlines flight out of Tan Son Nhut. The secretary was beside herself with worry about her husband, but he came out safely on one of the helicopters.

I spent two days in Hong Kong, bringing friends at the consulate general up to date, then flew on to Honolulu, where our son was enrolled in college. I waited there on the remote chance that the situation in Vietnam would indeed stabilize, in which case I intended to turn around and fly back. When Saigon fell, I sadly continued my journey to Washington.

This article was written by Richard W. Hale and originally published in the June 2003 issue of Vietnam Magazine.

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Vietnam Magazine today!