Black April, by George J. Veith, Encounter Books, 2012

Black April, by George J. Veith, Encounter Books, 2012

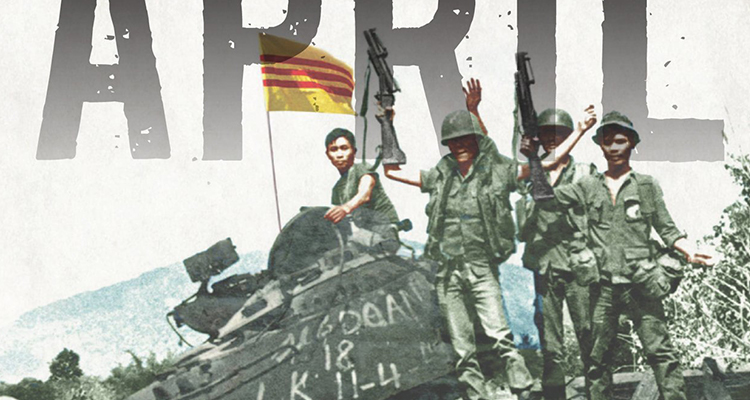

George Veith’s illuminating examination of South Vietnam’s fall is based on two premises: The Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) was better than the Western impression of it as a corrupt, ineffectual fighting force; and the U.S. political system—Congress—was largely responsible for the lion’s share of the ARVN defeat by refusing to send aid.

Veith’s work, unlike Alan Dawson’s contemporaneous 1977 account, 55 Days: The Fall of South Vietnam, depicts President Nguyen Van Thieu in a more even light—as a shrewd, Machiavellian politico versus Dawson’s quintessentially corrupt leader. Veith details events that accelerated the inevitable Greek tragedy of capitulation. The 1973 Yom Kippur War drew down American reserve war stocks for an Israeli ally perceived to be more durable than the Vietnamese. The Arab oil embargo hampered the Vietnamese air force and spurred a worldwide recession. Finally there was the political destruction of President Richard Nixon, the last commander in chief with the will and commitment to continue support.

Watergate ran amok in the summer of 1973, six months after the Paris Peace Accords. The secret bombing of Cambodia led an angry Congress to pass the Case-Church Amendment in June, barring U.S. air attacks in Cambodia and prohibiting the reintroduction of combat forces in Indochina without Congressional approval. This led to the War Powers Resolution that fall, aligning the Congressional attitude with the war protesters and the far left proponents of cutting all ties to Vietnam.

These actions and events backdrop a Peoples’ Army of Vietnam (PAVN), seasoned by the Tet defeats in 1968 and the 1972 Easter Offensive, employing in the spring of 1975 an immutable military axiom—the principle of mass—by stripping the North of combat units and pushing them south with a new sense of purpose and flexibility. Black April skillfully describes the staggering logistics required for this effort.

North Vietnam’s previous dogmatic adherence to plans and centralized command and control, which prevented junior commanders’ from exploiting tactical advantages on the battlefield, had been its Achilles’ heel. Now, speed and flexibility, necessary to ensure the destruction of the regime in the South, were emphasized by Vo Nyugen Giap and other Politburo members.

Strategically, the PAVN’s strike into II Corps’ Central Highlands undermined the vertically deployed combat power of the ARVN, which was strung from the I Corps in the north to the Delta’s southernmost IV Corps. The PAVN’s push into the Highlands was akin to cutting the country in half.

Veith skillfully depicts the Politburo’s personalities and egos and the alliances that required diplomatic navigation by PAVN field commanders. Despite this, the unanimity of the PAVN leadership contrasts sharply with Thieu’s closely held leadership aimed primarily at defeating political rivals.

Veith gives a fair and balanced assessment of the South’s fighting forces by describing instances of heroic action as well as wholesale panic. Ranger, Airborne and regular ARVN battalion and brigade commanders largely stood with their troops until overwhelmed, while more senior staff officers frequently escaped.

Black April is part one of a two-volume treatment of the war’s conclusion and is a tremendous addition to the history of the conflict. The second volume will examine the political and diplomatic efforts to implement the Paris Peace Accords and efforts to arrange the cease-fire in April 1975.

—Review by Bill Jordan