So observed Theodore Roosevelt after the shoot-out in Las Guásimas in Cuba. His first experience of combat was almost his last.

Private Charles Johnson Post of the 71st New York Volunteers sat on the berm of his muddy trench on “Misery Hill,” peered through the darkness at Santiago, and thought about mutton chops and ice-cold beer. His regiment had participated in the V Army Corps’s costly assault on the San Juan Heights on July 1, 1898. Almost immediately, heavy rains had gridlocked the narrow supply trail from Siboney on the coast. Malarial fevers and dysentery had struck the army. There was little food, no medicine, and–worse yet–no tobacco. The troops were soaked by morning rains, boiled by the afternoon sun, haunted by the absence of dead comrades.

Post heard the clink of a glass bottle against a tin mess cup. Artillery Captain Allyn K. Capron’s dog tent was pitched just behind him. Capron drank at night, murmuring to himself and sobbing. “I’ll get ’em, Allyn, I’ll get ’em, goddamn ’em.” He would repeat himself, over and over, slurring the words, and then fade off to sleep.

Post and the other troops in the trench sympathized with the old man. Caprons had fought in every war since the Revolution. Now Allyn Capron, Jr., the captain’s son, was dead, killed two weeks earlier at a little hamlet called Las Guásimas.

Named after the hognut trees that grew at the junction of two jungle trails, Las Guásimas is today an all but forgotten scrap, overshadowed by the battle for the San Juan Heights a week later and the destruction of the Spanish fleet along the shores west of Santiago on July 3. It probably involved no more than 3,000 men and lasted just over an hour. But it committed Major General William Rufus Shafter to a course of attack that brought near disaster to the V Army Corps; featured an all-star cast that included Leonard Wood, Theodore Roosevelt, John J. Pershing, Stephen Crane, and Richard Harding Davis; typified the rambunctious nature of the American fighting in the war with Spain; and almost killed the man who would become–thanks in part to the battle itself–the 26th president of the United States.

Roosevelt had reached Las Guásimas by a circuitous route. In April 1897, President William McKinley had appointed him assistant secretary of the navy. Lamenting Spain’s “murderous oppression” of a Cuban uprising that had been going on for two years, he began to ready the navy for war. Then, on February 15, 1898, the battleship Maine blew up in Havana Harbor. A month later, a naval court of inquiry fixed the blame on a mine. In April, the United States declared war. Roosevelt, who had no intention of sitting out the conflict in Washington as an armchair jingo, immediately resigned his navy post, secured an army commission with the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, and ordered a lieutenant colonel’s uniform from Brooks Brothers.

Secretary of the Navy John Long thought it an act of folly. He wrote in his diary that Roosevelt would end up on the Florida sands swatting mosquitoes. Still, “how absurd all this will sound if, by some turn of fortune, he should accomplish some great thing and strike a very high mark.”

The commander of the regiment was Colonel Leonard Wood, recently White House physician to McKinley, and before that a dogged Indian fighter who had won the Medal of Honor campaigning against the Apache rebel leader Geronimo, For a while the press tabbed the regiment, largely composed of cowboys and marksmen from Texas and the Arizona, New Mexico, and Indian territories, “Wood’s Wild Westerners.” The name didn’t stick. “Roosevelt’s Rough Riders” soon became the favored sobriquet.

At the last minute, a number of what Roosevelt called “gentleman rankers,” Ivy League graduates with formidable sports credentials, qualified for the regiment. As Stephen Crane, reporting for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, wrote, “Lean slit-eyed plainsmen with names like Cherokee Bill and Rattlesnake Pete served beside men from Boston’s Somerset Club and the Knickerbocker Club of New York.”

Wood and Roosevelt assembled the frontiersmen and blue bloods in San Antonio for cavalry training. They were soon honed to a fighting edge. Roosevelt was confident they could have whipped Caesar’s Tenth Legion. At the end of May, they entrained for Tampa, Florida, where General Shafter, at 300 pounds perhaps the most corpulent man in the army, struggled ineffectually amidst a bedlam of incoming troops and war matériel to ready the V Army Corps for embarkation.

There were inevitable delays, but on June 14 some 17,000 men finally departed for Cuba in a hastily improvised gaggle of army transports. At the last moment, Wood was advised there was room for only eight of his 12 troops, about 90 to 100 men each, and horses only for the officers. The Rough Riders would have to fight on foot.

The army, which had originally planned to assault Havana, instead went to Santiago on the southeastern coast, because Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete’s squadron of cruisers was there. The capture or destruction of his fleet was the key to a swift ending of the war; the city itself, four miles north of the harbor entrance, was of little military consequence. When Shafter arrived off Santiago on June 20, Rear Admiral William Thomas Sampson urged him to assault the poorly defended heights of Morro and Socapa, guarding Santiago Bay. That done, Sampson could remove the mines and the log and chain booms at the entrance, steam his ships in, and engage Cervera’s fleet.

Shafter had seen the imposing heights guarding the harbor entrance. He had little stomach for a direct assault-even if, as reported, they were armed with 18th-century cannon. While he had been ordered to cooperate earnestly with Sampson “in destroying the Spanish fleet,” he had also been given tactical latitude. He advised Sampson that he would land at Daiquirí, a town some 18 miles southeast of Santiago. Sampson, confused, agreed to assist the landing but still assumed Shafter would move troops westward down the railway line that hugged the coast, under the protection of the fleet’s guns, and hit the Morro bastion from the flank.

The landing at Daiquirí began on Wednesday morning, June 22. Lighters, lifeboats, and launches brought the troops through heavy swells and tried to land them on a single decrepit dock or on the beach through dangerous surf. Horses and mules were simply pushed overboard. “We disembarked,” Roosevelt reported, “higgledy-piggledy.” Fortunately, there was no Spanish resistance. By evening, Shafter had gotten 6,000 men ashore and Brigadier General Henry W. Lawton started two brigades of his 2nd Infantry Division westward along the seven-mile road to a town called Siboney.

Shafter, still headquartered offshore on the Seguranca, had ordered Lawton, or the “senior officer at the front,” to occupy Siboney, digin, and cover subsequent landing operations. Lawton camped on the road for the night and took the undefended town around nine o’clock on Thursday morning. Brigadier General Jacob Ford Kent’s 1st Infantry Division followed.

At the time, the Rough Riders and the other regiments in the Cavalry Division were still encamped at Daiquirí. The commander, Major General Joseph (“Fighting Joe”) Wheeler, was not used to bringing up the rear-dismounted or otherwise. A frail, 61-year-old Alabamian, barely over five feet tall, white-haired and white-bearded, Wheeler had achieved the rank of lieutenant general in the Confederate army at the age of 28. When McKinley, seeking to heal old wounds, asked him to serve, Wheeler agreed. He had no qualms about putting on a Union uniform; if he had to greet Robert E. Lee at the heavenly gates dressed in blue, so be it.

Fighting Joe finally got some of his cavalry going on Thursday, June 23, and the troopers reached Siboney early that afternoon. Wheeler promptly set up his headquarters, conferred with Cuban general Demetrio Castillo, whose insurgents had sparred with Spanish troops that day, and made a short reconnaissance up the trail that led to Las Guásimas. On his return, he met with his brigade commander, Brigadier General Samuel B. Young, who proposed a reconnaissance in force.

Without question, Wheeler was eager to steal a march on the infantry. The order to entrench along a miasmic coastal strip less than four miles from a large Spanish force struck him as unwise. He spotted a loophole in Shafter’s order delegating command ashore to Lawton or the senior officer at the front. Almost certainly, that meant the senior officer in Lawton’s absence. But Lawton was not absent; moreover, the intent of the directive clearly was to take up defensive positions. Major General Wheeler, however, outranked any officer ashore. He quickly approved Young’s request.

The Rough Riders barely made the escapade. They had landed on Wednesday, helped to unload the transports, entrenched, then set out at a forced march down the grandly named Camino Real (Royal Road) to Siboney on Thursday in the murderous midafternoon heat. The narrow, tortuous, hilly trail took its toll; the regiment scrambled into the town long after nightfall, shuffled past Lawton’s entrenched infantry, and camped at what Roosevelt called “the extreme front” of the American line. Soon afterward, a tropical downpour drenched the campsite. When the rain finally stopped, the troopers fired up hardtack and tried to dry out. By the flickering light, Roosevelt looked over at Captain Allyn K. Capron, Jr.–whose 27th birthday was only minutes away. Roosevelt thought him perhaps the best soldier in the regiment. Wood was telling Capron of Wheeler’s plan. “Well,” said Capron, “tomorrow at this time the long sleep will be on many of us.”

It was after midnight when they finally turned in. Reveille was set for 3:15 am. Exhausted as they were, it was hard to sleep. Richard Harding Davis–”Richard the Lion-Harding,” as fellow reporters and New York society called the impeccably dressed New York Herald correspondent, who had modeled for the escort to Charles Dana Gibson’s “girl”–recorded the Surrealistic nighttime scene as additional troops came ashore from transports off Siboney in the glare of searchlights: “It was a pandemonium of noises. . . . The men already on shore were dancing naked around the camp-fires on the beach . . . shouting with delight . . . and those in the launches as they were pitched headfirst at the soil of Cuba, signalized their arrival by howls of triumph.” Three miles to the north, General Antero Rubin’s Spanish troops felled trees in the jungle to improve the defenses on the ridge overlooking Las Guásimas.

Two paths led northward from Siboney to the crossroads at Las Guásimas. The Camino Real, the eastern route, led up a marshy valley between two ranges of hills. It was, for the most part, wide enough for wagons. The path to the west, little more than a trail, followed a ridge line roughly parallel to the road, The two routes were never more than about a mile apart, but jungle vegetation made it impossible to see one from the other.

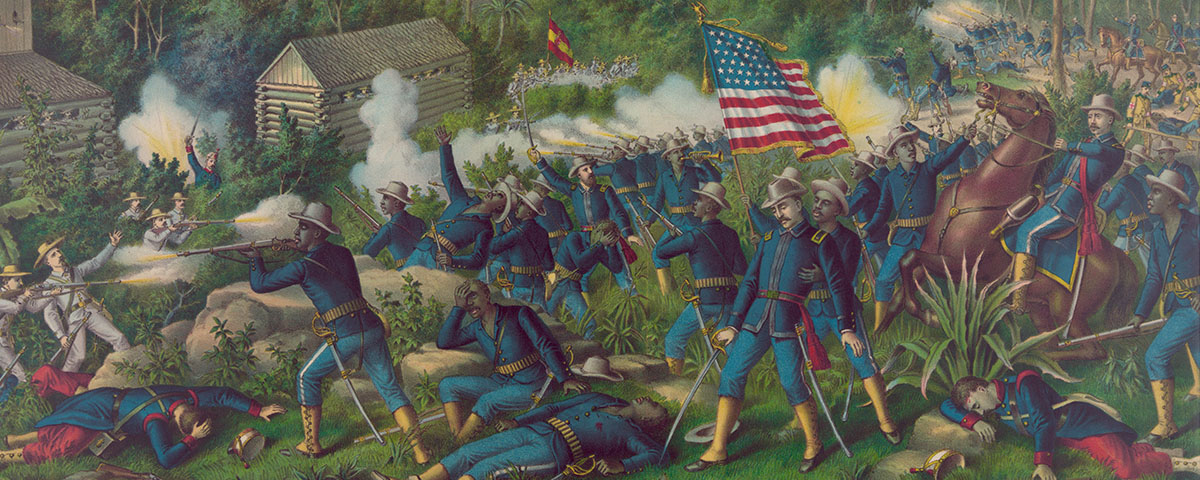

Wheeler’s plan called for Young to lead four troops of the 1st Regular Cavalry and four more of the 10th Regular Cavalry (a regiment of black soldiers), with two Hotchkiss mountain guns, down the Royal Road. Wood would take his eight troops up the more difficult ridge trail. General Castillo had promised to support them with 800 insurgents; only a handful of scouts materialized. Half a dozen correspondents did, too, including Davis and Stephen Crane. Altogether, Wheeler’s force numbered fewer than 1,000 men.

The early reveille on Friday, June 24, was particularly hard on the Rough Riders. Correspondent Edward Marshall of Hearst’s New York Journal observed that even Wood looked haggard. Young got his better rested troops down the valley road at 5:45 am. The Rough Riders started up the steep trail above Siboney promptly at 6:00. A regular army major looked at the casual volunteers with disdain. “Goddam it–they haven’t even got a point out”

The regulars tramped easily down the valley road, but the hillside at Siboney took its toll on “Wood’s Weary Walkers.” Kennett Harris of the Chicago Record pictured “Capron’s tall figure striding over the boulders in the steep ascent.” For many of the dismounted cavalry, however, it was a tough scramble. Crane, who had landed at Siboney from a dispatch boat just as the troopers crested the hill, struggled to catch up. To him, the jungle “seemed almost upon the point of crackling into a blaze under the rays of the furious Cuban sun.”

Davis, dressed in a blue jacket, white shirt, and felt hat banded with a white puggaree, had attached himself to the Rough Riders. Riding along with Roosevelt toward the front of the column, he took a casual view of the mornings expedition: “I doubted that there were any Spaniards nearer than Santiago.” Roosevelt grumbled a bit at the pace Wood was setting but found the tropical forest beautiful and peaceful.

Crane confessed that he knew little about war–his 1895 novel The Red Badge of Courage was an imagined drama–but he had landed with the marines at Guantánamo on June 7 and endured the fierce fighting there for a week. Obviously, the Spanish had picked up elements of guerrilla warfare from the Cubans. As he pushed along the narrow path leading through the jungle, the jovial babbling of the volunteers terrified him.

By now Wood had established points: first, two Cuban scouts; behind them, five trailers under Sergeant Hamilton Fish; then young Allyn Capron’s troop of 60 men. Wood and the rest of the regiment followed. But it was impossible to put out flankers; Davis observed that “the dense undergrowth and the tangle of vines that stretched from the branches of the trees to the bushes below made it a physical impossibility for man or beast to move forward except along the beaten trail.”

To the east, shortly before 7:30, Young paused in an open glade to regroup. Captain A.L. Mills and two troopers advanced about 150 yards toward the ruins of an old building with a sundial on its side. There, several hundred yards to the north, they spotted breastworks. The Spanish line appeared to be in the shape of an obtuse triangle, with the salient jutting toward the space between the advancing American forces. Young, alerted to the situation, deployed the 1st Cavalry to both sides of the road while holding the 10th in reserve. General Wheeler joined him, and Young pointed to the straw hats jutting up from the breastworks.

Up on the ridge, Wood’s advance scouts came across the body of a dead soldier–whether Spanish or Cuban was not clear–that Castillo had reported to be only a few hundred yards from the Spanish lines. Capron gave the news to Wood, who ordered silence in the ranks. Crane, still thinking that “this silly brave force was wandering placidly into a great deal of trouble,” heard a sergeant bawling, “Ah say, can’t ye stop talkin’?”

Wood ordered Roosevelt to deploy three troops to the right of the trail while Major Alexander Brodie took two more off to the left. Roosevelt later recalled that parade-ground etiquette called for the men to be deployed into a line of squads and then the order given: “As skirmishers, by the right and left flanks, at six yards, take intervals, march.” What actually came out was “Scatter out to the right there, quick, you! Look alive!”

Across a ravine that ran northwest past the Spanish salient, Wheeler proposed to Young that they fire a round from one of the Hotchkiss one-pounders at the straw-hatted troops at their front. As the shell whined off, Captain William D. Beach, chief engineer of the Cavalry Division, pulled out his notebook and jotted down the time: 8:15 am. Then his hand jerked as a terrifying volley of rifle fire erupted from the breastworks. Wheeler, too, was staggered by the volume of fire–it seemed greater than anything he had experienced in the Civil War. Nearby, an enlisted man and several officers crumpled to the ground.

Over on the hill trail, as the Rough Riders deployed, a fusillade of bullets ripped through the air. Crane knew the sound of the Spanish rifles: “The Mauser says ‘Pop!’–plainly and frankly pop like a soda water bottle being opened close to the ear.”

“Everyone went down in a lump without cries,” Edward Marshall noted, but the chug “of bullets striking flesh is nearly always audible.”

In the first minutes of the battle on the left, the point men went first. Sergeant Hamilton Fish, grandson of Ulysses S. Grant’s secretary of state, was hit by a slug that entered his left side, tore out his right, and slammed into the chest of Private Ed Culver, who was part Cherokee. Fish had time only to gasp, “That bullet hit both of us,” before he died. Culver gazed blankly at Fish, then crawled back along the trail. Private Tom Isbell, another Cherokee on point, thought he saw a Spaniard and fired at him. His shot triggered a vicious volley from the underbrush. Isbell was severely wounded by seven bullets, three in the neck. In just three minutes, Davis estimated, “nine men were lying on their backs helpless.”

Wood had ordered Roosevelt to try to connect with the regulars. “In theory this was excellent, but as the jungle was very dense the first troop that deployed to the right vanished forthwith, and I never saw it again until the fight was over,” Roosevelt later observed. “I managed to keep possession of the last platoon. One learns fast in a fight.”

Roosevelt was astonished by the smokeless Mausers; the enemy was “entirely invisible.” Fortunately, the Rough Riders were equipped with the .30-caliber Krag-Jorgensen carbine, which also fired a smokeless cartridge. Roosevelt had faced down an old-line supply corps officer in Washington who wanted to provide his men with black-powder Springfields, on the theory that the smoke would conceal them from the enemy.

Davis had followed Roosevelt into the underbrush to the right of the trail. He and Roosevelt came to an outcropping that jutted out over a ravine. Beyond was a ridge. Davis, on his stomach, was scanning the ridge with his binoculars when he suddenly spotted the conical hats of the Spanish troops. “There they are, Colonel. Look over there!”

In turn, Roosevelt pointed them out to the men around him, got more troopers up on the line, and ordered quick firing. Flushed from their cover, the Spanish retreated up the ridgeline. Apparently they were hurt, and the Rough Riders, dodging behind bushes and trees, went after them. As Roosevelt hunkered down behind a large palm and cautiously peered out to one side, “a bullet passed through the palm, filling my left eye and ear with the dust and splinters.” Roosevelt later made light of his brush with death, noting only that it was “fortunate” his head was not behind the tree.

The firing was now less intense, and Roosevelt’s troopers continued to deploy to the right. Soon they saw soldiers in the valley beyond the ravine. They appeared to be American, but their first action was to fire off a volley at the Rough Riders. Sergeant Joseph Jenkins Lee, one of Roosevelt’s gentleman rankers, scrambled up a tree and flogged the air with his red-and-white banner. The guidon of the 10th waved back. Then skirmishers from both regiments fanned out to connect the line, securing Wood’s right wing.

Feeling he was not doing enough fighting “to justify his existence,” Roosevelt thought it time to rejoin the regiment near the trail where the firing was now heaviest. He began trotting back to the left. In the thick growth, his sword got between his legs and tripped him up. The refrain of an old fox-hunting song kept jingling through his head: “Here’s to every friend who struggled to the end.” Finally he found Wood, who told him to take command of the left wing, since Major Brodie had been wounded.

Davis followed, passing dead men, and came to a dressing station at the point where the cavalrymen had first stopped. He noticed “a tall, gaunt young man with a cross on his arm approaching . . . carrying a wounded man much heavier than himself across his shoulders.” He realized he had seen the doctor before at “another time of excitement and rush and heat.”

William Randolph Hearst had paid Davis richly to cover the Yale-Princeton football game in 1895, and suddenly Davis remembered: “He had been covered with blood and dirt and perspiration as he was now, only then he wore a canvas jacket and the man he carried was trying to hold him back from a whitewashed line. And I recognized the young doctor . . . as ‘Bob’ Church, of Princeton.” Church had won the approval of his college peers that day; on this one, he would win something more–the Medal of Honor.

To Davis, it sounded as though the firing had moved half a mile forward; the Spaniards had been driven back. He trotted down the trail toward the front, despondently noting the horrors of war. “The rocks on either side were spattered with blood and the rank grass was matted with it.” Through the whining of bullets he heard “the clatter of the land-crabs, those hideous orchid-colored monsters that haunt the places of the dead.” Later he would see the corpse of a trooper whose eyes were torn out and lips ripped off.

He came across Lieutenant John R. Thomas, Jr., lying on a blanket, half-naked, soaked in blood from a wound in his leg. He was raving deliriously, ordering attending medics to carry him to the front. “You said you would! They’ve killed my captain–do you understand? They’ve killed Captain Capron. The–Mexicans! They’ve killed my captain.”

Capron was lying only 50 feet away, a big black open spot on his chest. Davis plodded on, his boots slipping over loose stones and Mauser shell casings.

Edward Marshall, conspicuous in a white coat, was also hit. He carried a revolver and, correspondent or not, had been firing away “cheerfully.” Suddenly there was a chug, and Marshall fell wounded in the long grass.

Crane was not far behind him. A passing soldier told him, “There’s a correspondent up there all shot to hell.” He led Crane to the spot where his friend and rival was lying. “Hello, Crane,” Marshall said.

“Hello, Marshall. In hard luck, old man?” “Yes, I’m done for.” He asked if Crane would file his dispatches–not ahead of his own, “but just file ’em if you find it handy.”

Crane got some soldiers to carry Marshall on tent canvas to a dressing station. Then he trudged wearily back toward Siboney to file his own dispatches for Pulitzer’s World and Marshall’s for Hearst’s Journal. In the fierce battle for circulation between Hearst and Pulitzer, there was no room for compassion. Crane’s act of perceived betrayal cost him his job when he returned to the United States in July. Hearst promptly offered him employment.

Meanwhile, down in the valley, Captain Beach listened nervously to the Spanish volleys. The advance had stalled, and casualties were piling up. All the troopers were now on the line; there were no reserves. He turned to Wheeler and reminded him there were nine regiments of infantry at Siboney, only a few miles back up the road. “Let me send to Lawton for some of them and close this action up.”

Wheeler hesitated. The idea had been to steal a march on the infantry, not call on them for rescue. The vision of a Spanish counterattack rolling up his exhausted cavalry and surging down to the valley to strike the jumble of troops on the beachhead may have made up his mind. He nodded. “All right!” Beach called for an orderly and sent him off to Siboney at a gallop.

By the time Crane approached Siboney, bugles were sounding urgently. “The heroic rumor arose, soared, screamed above the bush,” he wrote.” Everybody was wounded. Everybody was dead.” He watched the 9th Regular Cavalry and the 71st New York Volunteers dash into formation. There was no roll call, Private Post of the 71st remembered. Just ” ‘Fall in–fall in! Count off. . . . Fours right!’ And we were off.”

At the field dressing station, surrounded by wounded troopers, Edward Marshall, his spine shattered by the Spanish bullet, heard a man quietly begin to sing:

My country tis of thee,

Sweet land of liberty . . .

Most of the men joined in. Marshall remembered that “the quivering, quavering chorus, punctuated by groans and made spasmodic by pain, trembled up from that little group of wounded Americans in the midst of the Cuban solitude.” Shortly afterward, Marshall was carried to Siboney by other Hearst reporters and placed on a hospital ship. Though crippled by his wound, he survived.

At the front, Davis continued down the trail, carrying a carbine. He could see Roosevelt on a slight upward slope, rushing his men forward toward an old ranch house that anchored the Spanish right.

Roosevelt took a rifle from a wounded man and fired a few experimental shots at the red-tiled ranch buildings. “Then we heard cheering on the right, and I supposed this meant a charge on the part of Wood’s men, so I sprang up and ordered the men to rush the buildings ahead of us.”

The charge erupted all up and down the American line. On Wood’s right, the black troopers of Young’s 10th Cavalry surged up the hill. One of their white officers, Lieutenant John J. Pershing (known as “Black Jack” to white soldiers because of his admiration for the black troopers), noted that the 10th “opened a disastrous enfilading fire upon the Spanish . . . thus relieving the Rough Riders from the volleys that were being poured into them.”

In amazement and admiration, Davis watched the exhausted Rough Riders scramble up the hill. “It was called “Wood’s bluff afterwards,” he wrote, “for he had nothing to back it up with. . . . The Spaniards naturally could not believe that this thin line. . .was the entire fighting force against it. . . . As we knew it was only a bluff, the first cheer was wavering, but the sound of our own voices was so comforting that the second cheer was a howl of triumph.”

The Spanish fired a few volleys, then broke and ran. Without thinking, Joe Wheeler launched a cry he had not shouted in more than 30 years: “Come on, boys, we’ve got the damn Yankees on the run!”

“When we arrived at the buildings,” Roosevelt recalled, “panting and out of breath, they contained nothing but heaps of empty cartridge-shells and two dead Spaniards, shot through the head.” It was all over. On the right wing, the punctilious Captain Beach checked his watch. It showed 9:20. In disbelief, he put it to his ear. The timepiece was ticking. The battle had in fact lasted just over an hour.

The infantrymen coming up to support the Rough Riders were forming up for action, Post wrote, when “the popping grew fainter; then there were no shots at all. We realized that the fight was over.” One of the 71st hailed a wounded Rough Rider along the trail. “Yeah, we knocked hell out of them’ was the response.”

In fact, eight Rough Riders were dead and 34 wounded. Young’s force had also suffered eight deaths, and 18 had been wounded. (Spanish losses were officially recorded as 10 killed and 25 wounded, but they were probably greater.) The first press accounts, written in Siboney by correspondents who had not made it to the front, reported that the Rough Riders had rushed blindly and recklessly into a trap. Crane’s dispatch for the World called the foray “a gallant blunder.”

Davis, who had thought the prospect of battle remote as he rode down the jungle trail, wrote to his family, “We were caught in a clear case of ambush.” On reflection, he modified his stand: “There is a vast difference between blundering into an ambuscade and setting out with the full knowledge that you will find the enemy in ambush.” Roosevelt asserted that “there was no surprise; we struck the Spaniards exactly where we had expected.”

In fact, ambushed or not, and whether or not the Spanish had planned to withdraw all along, as one of their accounts later had it, the Rough Riders and Youngs troopers had shown extraordinary courage in driving back a superior enemy force, variously estimated at from 1,200 to 4,000 men, well entrenched, well armed, and hidden from view on the jungle heights above the trails. A Spanish soldier later explained, “The Americans were beaten, but persisted in fighting.”

As to Wheeler’s precipitate advance, Roosevelt observed trenchantly that “war means fighting; and the soldier’s cardinal sin is timidity.” Wheeler was “a man with ‘the fighting edge.’ ” The Rough Riders were “children of the dragon’s blood.”

Lawton reportedly wagged a finger at Wheeler and told him that he, Lawton, was in charge of the advance until Shafter came ashore, and that Wheeler should corral his venturesome cavalry. Shafter congratulated Wheeler but firmly warned him to hold his position “until all the troops are well in hand.”

Later, Shafter claimed he had always intended to attack Santiago directly by way of the inland route rather than assault the Morro and Socapa fortifications at the harbor entrance, but this was not the impression he had given Admiral Sampson and others. Whatever his intent when he landed at Daiquirí, Shafter, with Las Guásimas in hand, was now committed to the perilous overland route that shattered the V Army Corps in the bungled, chaotic attack on El Caney and the San Juan Heights a week later.

By the time that was over, Shafter’s army had taken 1,200 casualties in its blunt thrust toward Santiago, his men were strung out along the heights in vulnerable positions, and he still had not seized the Morro bastion or the Socapa batteries guarding the harbor entrance. Even Roosevelt felt, “We are within measurable distance of a terrible military disaster.” Shafter strongly considered retreat and plaintively asked Admiral Sampson to force the heavily guarded harbor entrance. Sampson demurred.

Then, on July 3, Admiral Cervera made a courageous but doomed attempt to escape the American blockade. The total destruction of the Spanish squadron firmed up Shafter’s resolve, and he demanded the surrender of Santiago and all the Spanish troops in the region. Two weeks later, even as malarial forces prostrated his V Corps, he got it.

As for Roosevelt, he thought the fight at Las Guásimas “really a capital thing for me, for practically all the men had served under my actual command, and thenceforth felt enthusiastic belief that I would lead them aright.” And when the second batch of press reports, notably those of Davis and the dispatches Crane filed for Marshall, lauded the courage of “Roosevelt’s” Rough Riders and the importance of their victory, a group of independent Republicans announced that it would run him for governor of New York in the fall.

Thus, with Las Guásimas, Roosevelt began his charge into history as the hero of Kettle and San Juan hills on the heights, governor, vice president, and, on McKinley’s assassination, president. As historian Walter Millis noted, the “hurried hour in the bush above Siboney was largely instrumental in giving us our next President of the United States.”

MICHAEL BLOW, a free-lance writer, is the author of A Ship to Remember: The “Maine” and the Spanish American War (William Morrow, 1992).

[hr]

This article originally appeared in the Summer 1995 issue (Vol. 7, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: “One Learns Fast in a Fight”

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!