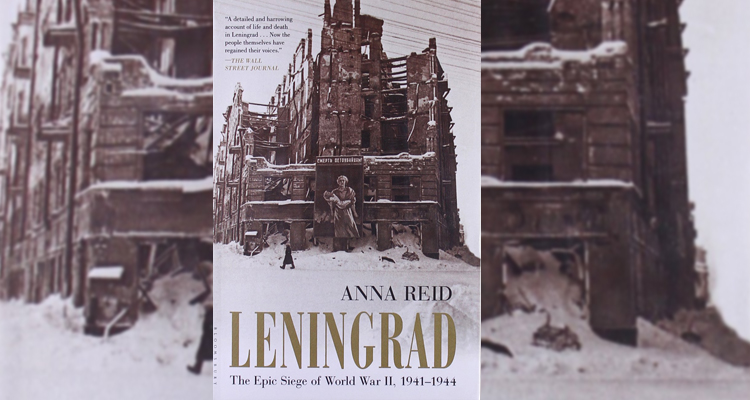

Leningrad

The Epic Siege of World War II, 1941–1944

By Anna Reid. 512 pp. Walker & Company, 2011. $30.

Reviewed by Robert M. Citino

All wars are horrible. Even the grandest victory generates suffering and death, maimed and mutilated bodies, wrecked lives and families. The tale Anna Reid tells here fully earns its place in this hall of horrors. Imagine a city of three million—Chicago, let’s say—cut off from the outside world for almost three years. No one gets out, no supplies get in. Imagine how soon the shelves at the grocery store go bare. Imagine burning your furniture a chair leg at a time to heat your home. Imagine watching your children starve to death.

Leningrad is a tough read, certainly, but perhaps that is all the more reason why we should read it

That is precisely what happened to Leningrad in World War II. Cut off from the rest of Soviet Russia by the onrushing Wehrmacht in the opening months of Operation Barbarossa, Leningrad (formerly and currently known as St. Petersburg) was left to its own devices, and they turned out to be grossly inadequate. Food disappeared and so did fuel. The dead piled up in the street, and there were many incidents, now substantiated, of cannibalism—corpses eaten for food and people killed so that they could be eaten. In that first horrible winter of the siege, about 500,000 civilians starved to death.

Leningrad is a tough read, certainly, but perhaps that is all the more reason why we should read it. Reid has plumbed a huge mass of material, especially the memoir literature from siege participants and survivors. You get to know these people, many of them highly literate cosmopolitans, and you are at their side as they “fall down the funnel” in late 1941.

Some days they got a ration of only 125 grams of bread—three thin slices, often adulterated with God knows what. Some days they ate joiner’s glue, made from the remains of slaughtered animals. Some days they ate cold cream and industrial casein. Too often, they ate nothing at all.

After the war, the siege of Leningrad became a victim of memory politics. In a land where the government did nothing but lie, there was at first denial that anything bad had happened. Admitting it would have meant admitting official incompetence. In the 1980s, functionaries of Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev made a cult of the Great Patriotic War. While they admitted everything, they also made heroes of the victims. No one grumbled, the new account went, no one despaired, no one stole. Only since the collapse of the Soviet Union have more truthful and balanced views come to the fore.

Reid’s verdict? The Soviet government botched its handling of Leningrad from the start. No one drew up evacuation plans, although food was running out within weeks of the invasion. Belatedly, the authorities decided to evacuate the children and disperse them to towns around Leningrad—some into the very path of the German advance. By the time the Soviets ordered a general evacuation, it was too late: The roads were closed. All the while, the regime spent a great deal of energy doing what it did best: rounding up and shooting “grumblers” and “defeatists,” virtually all of whom were innocent of any crime.

The Wehrmacht was ultimately responsible for this human catastrophe, of course, but Reid is certainly correct when she avers that a more competent regime would have prepared the city better, evacuated it more promptly, and saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of people.

Robert M. Citino is a professor of history at the University of North Texas and blogs for World War II magazine at www.WorldWarII.com.