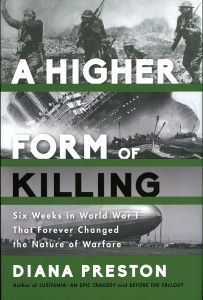

A Higher Form of Killing

A Higher Form of Killing

Six Weeks in World War I That Forever Changed the Nature of Warfare

By Diana Preston, 352 pages.

Bloomsbury, 2015. $28.

Reviewed by Anthony Brandt

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION. The phrase dates to the Spanish Civil War but the reality dates to World War I, when in a six-week period in spring 1915, the German U-20 torpedoed the SS Lusitania, Zeppelins attacked London from the air, and poison gas was used by the Germans for the first time on the battlefield. Those six weeks, and their aftermath, are the subject of British historian Diana Preston’s fascinating, and horrifying, new book.

In the case of the Lusitania—the subject of one of Preston’s previous books—the sinking broke internationally accepted “cruiser rules” against attacking civilian passenger ships. More than a thousand people died. The Zeppelins killed an equal number of British civilians, including women and children; the dirigibles also dropped incendiary bombs in an attempt to set London afire. After the Allies gained control of the skies, the firebombing of entire cities became common. As for poison gas, it was released from canisters when the wind was right to blow it over enemy trenches. Yet using poison gas in the trenches was an uncertain gamble, as the wind could change, and sometimes did, blowing the gas back over the very troops who had released it. During the course of the war, Germany first developed chlorine gas, then phosgene, and finally the deadliest, mustard gas, forcing Britain, France, and later, the United States, to develop their own chemical weapons.

Preston is an excellent historian who has written a good deal of military history, and she tells the stories behind the new weapons with great skill and detail. As an example, the wife of Fritz Haber, the German chemist who developed the poison gases, hated what her husband was doing, fought to get him to change his mind, and, when she failed to do that, took his pistol and shot herself. Haber did not attend her funeral.

As to the Zeppelin raids, although Londoners panicked and piled into cellars or any safe spot they could find, they were also fascinated by the giant machines floating above them like pink cigars. Wrote the Guardian: “One of the blackest of the many crimes with which Germany has stained herself this past year is that she has introduced this inevitably haphazard murder into warfare.”

Near the end of the war, the Germans were building large bombers with enormous wingspans to bring heavier and heavier bombs to England, while the United States was working “on sixty-five gas projects including one gas that would leave soil barren for seven years and a few drops of which would cause a tree ‘to wither in an hour.’” Germany had opened Pandora’s box. Evil would flow out of it for half a century or more.

Anthony Brandt is a frequent contributor to MHQ. His most recent book is The Man Who Ate His Boots: The Tragic History of the Search for the Northwest Passage.

.jpg)