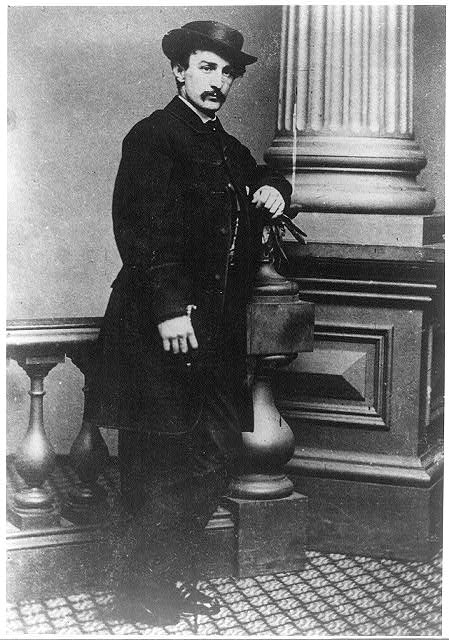

Facts, information and articles about John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of Abraham Lincoln

John Wilkes Booth Facts

Born

May 10, 1838, near Bel Air, Maryland

Died

April 26, 1865, near Port Royal, Virginia

Occupation

Actor

John Wilkes Booth Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about John Wilkes Booth

» See all John Wilkes Booth Articles

John Wilkes Booth summary: John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor, was a staunch supporter of slavery and the Southern Confederacy during America’s Civil War. On the night of April 14, 1865, he entered Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C., and assassinated Abraham Lincoln, 16th president of the United States. Although rumors claim President Zachary Taylor was assassinated with poison, the killing of Lincoln was the first presidential assassination known to have occurred in America’s history.

John Wilkes Booth Childhood

John Wilkes Booth was the ninth of ten children born to Junius Brutus Booth, a famous actor noted for his talent, his eccentric—some have said mentally unbalanced—nature, and his love of alcohol. The boy grew up in Baltimore and on a farm his father owned near Bel Air, Maryland, which was operated with slave labor. Like others of his family, John Wilkes Booth followed his father into the theatrical profession, making his stage debut in Baltimore at the age of 17. Joining a Shakespearian acting company based in Richmond, Virginia, some of his most respected performances were in the plays of Shakespeare.

When the fanatical abolitionist John Brown seized the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry in hopes of instigating a slave revolt in 1859, Booth joined the Richmond Grays, a militia unit sent to aid in his capture. He witnessed Brown’ execution for treason against Virginia a few weeks later.

The Election of Abraham Lincoln

The election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency in 1860 and the success of the anti-slavery Republican Party in the Northern states in that election were anathema to the actor. He later told his sister Asia Booth Clarke, “So help me holy God! my soul, life, and possessions are for the South.”

In November 1864, he wrote to a brother-in-law, “This country was formed for the white not for the black man. And looking upon African slavery from the same stand-point, as held by those noble framers of our Constitution, I for one, have ever considered it, one of the greatest blessings (both for themselves and us) that God ever bestowed upon a favored nation.”

Booth’s Thoughts Turn Bloody

He may have formed his first plot against Lincoln in 1861, planning to kidnap him before he could be inaugurated, but if so, a change in the president’s travel schedule thwarted the plan.

Booth’s acting career began to take off in 1860, and he continued in his profession during the war. Although not a great actor, his appearance would have garnered fans, especially among female theatergoers. He stood five feet, nine inches tall and was considered quite handsome with his curly raven hair and an ivory complexion. He, his brother Edwin and their father starred together in a standing-room only performance of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar—John played Marc Anthony, who came “not to praise Caesar, but to bury him”—in New York in 1864. Critics said he was good in the play, but not the equal of his father or brother.

On the night of November 9, 1863, he was performing in The Marble Heart , a popular melodramatic tragedy, on the stage at Ford’s Theater in Washington. Watching the play from the Presidential Box was Abraham Lincoln.

One of the women watching the play with the Lincolns was Mary B. Clay, daughter of the Kentucky abolitionist and minister to Russia Cassius Clay. She later wrote, “Twice Booth in uttering disagreeable threats in the play came very near and put his finger close to Mr. Lincoln’s face; when he came a third time I was impressed by it, and said, ‘Mr. Lincoln, he looks as if he meant that for you.’ ‘Well,’ he said, ‘he does look pretty sharp at me, doesn’t he?'”

Those words were written after Lincoln’s assassination, however, and tricks of memory may have embellished the events in her mind. The story first appeared in the Lexington, Kentucky, Herald and was quoted in The True Story of Mary, Wife of Lincoln, written by Katherine Helm, a niece of Mary Todd Lincoln. Helm said the events described took place in 1865; the November 1863 date is actually when Lincoln saw Booth in The Marble Heart.

During Lincoln’s second inaugural on April 11, 1865, Booth was present. A now-famous photograph of that gathering purportedly shows the actor in the crowd; if so, it was a remarkable piece of photographic serendipity, a photograph of Abraham Lincoln and John Wilkes Booth together in the same place, days before the assassination.

During his speech, Lincoln called for limited Negro suffrage—giving the right to vote to those who had served in the military during the war, for example. Hearing those words, Booth muttered to companions, “That means n—— citizenship. That is the last speech he will ever make.” He tried to convince one of those companions to shoot the president then and there.

Booth had become connected with the Confederate secret service, often meeting with other agents in Canada, Boston, and Maryland. In 1864, he had returned to the notion of kidnapping Lincoln, planning to hold him hostage in Richmond to exchange for thousands of Confederate prisoners of war.

He organized a group of co-conspirators to aid in his plans. Not everyone he asked to join him agreed to do so, but none seem to have reported his approaches to the authorities; Booth would only have chosen those who shared his views. He had come to the attention of authorities in 1862, however, when he was arrested in St. Louis and taken before the city’s provost marshal for making anti-government statements.

Lee Surrenders

On April 9, 1865, Robert E. Lee surrendered the largest Confederate army to Ulysses S. Grant, ending any remaining hopes for Southern victory and mooting Booth’s kidnapping plot. Instead, he and his companions would kill the president, vice president, cabinet members and perhaps Grant as well.

The Night Of Lincoln’s Assassination

When newspapers announced Lincoln and Grant would both attend Ford’s Theater on the night of April 14, Booth decided to strike. He had played Ford’s Theater for the second time just the previous month, and at any rate he was well known; his presence there did not arouse suspicion. Showing his card to a White House footman, he obtained entry to the box where Abraham and Mary Lincoln were enjoying the comedy Our American Cousin. Grant wasn’t there, only Major Henry R. Rathbone and his fiancé, Clara, seated on the far side of the box from where Booth entered around 10 pm. Booth almost certainly ascertained this before entering, by peering through a hole in the door that had been drilled so guards could check on the president without interrupting him. After entering, he secured the door with a wooden bar.

Absorbed in the evening’s entertainment, Lincoln was leaning forward and was unaware of Booth’s approach. The assassin shot him from behind, the bullet entering the left side of his head and lodging beneath an eye; Lincoln would linger through the night, dying a little before 7:30 the next morning. Rathbone leapt to seize Booth, who cut a deep slice in the major’s arm with a large knife before vaulting over the flag-draped rail of the box to the stage below. One foot caught on the flag, and he broke his leg when he landed. Most witnesses say he shouted the motto of Virginia, “Sic semper tyrannis” (“Thus always to tyrants”); others claim he said, “The South is avenged.” He may have shouted both before making his leg-dragging escape through a read door.

Booth On The Run

Doctor Samuel Mudd set the broken leg, and Booth avoided detection in Virginia for two weeks before a cavalry detachment cornered him and co-conspirator David E. Harold in a tobacco shed on the farm of Richard H. Garrett near Port Royal. Garrett’s son claimed his father had been afraid of the men when he acquiesced to their demands for a place to stay that night.

Harold surrendered, but Booth refused. The troopers set the shed on fire, a shot rang out, and Booth fell, mortally wounded. Whether he committed suicide or was shot by Sergeant Boston Corbett is uncertain. Most of those accused of conspiring with him were tried by a military tribunal and hanged, including Mary Surratt, who owned the boarding house where Booth stayed and met with his confederates in the days leading up to the assassination.

Booth had expected to be hailed as a hero of the South and was surprised to find his actions almost universally condemned. While their public expressions of regret were more muted than those of the North, Southerners feared Northern retaliation and dreaded the ascension of Vice President Andrew Johnson of Tennessee to the presidency, a man known to have no love for the Southern plantation class. John Wilkes Booth’s last public role had been a tragedy all around.

Afterthought: Booth’s Son Meets Lincoln’s Son

A footnote to the Booth-Lincoln story is often cited as one of the great ironies of American history. In 1863 or 1864, the Lincolns’ eldest son, Robert, on his way to Washington, was accidently crowded off a train platform in Jersey City, New Jersey. He was trapped in the narrow space between the platform and a train pulling out of the station when a hand grabbed his coat collar and pulled him to safety. Robert recognized his rescuer as one of the most prominent actors of the time—Edwin Booth. At the time of Lincoln’s assassination, Edwin was performing in Cincinnati, Ohio, and had to flee a mob.

A less-well known incident involving Robert Todd Lincoln and the Booths was related in Jason Emerson’s Giant in the Shadows: The Life of Robert T. Lincoln. In January 1869, attorney Robert Lincoln traveled to Escanaba, Michigan, in an attempt to resolve a debt owed to a client. In Escanaba, Robert stayed with the family of Eli P. Royce. A young nurse was also staying there, carrying for an invalid sister of Royce. When the nurse was asked to wait table at dinner and learned the guest was Lincoln’s son, she declared she would do it with a pistol in her hand. She was a niece of John Wilkes Booth. Her services with the family were immediately terminated.

Articles Featuring John Wilkes Booth From History Net Magazines

Featured Article

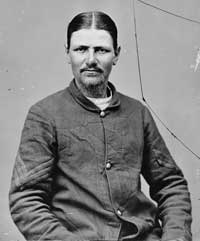

Crazy Boston Corbett Killed John Wilkes Booth

By Eric Niderost

Mad as a Hatter –

John Wilkes Booth’s killer achieved instant fame—but folks soon realized he was just plain crazy

John Wilkes Booth grimaced in agony as he staggered around inside a tobacco barn near Port Royal, Virginia, on April 26, 1865. His accomplice, David Herold, had already surrendered to troopers of the 16th New York Cavalry surrounding the barn, but the handsome actor who had shot President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre 12 days earlier refused to give up despite the pain of a fractured leg. For Booth and his pursuers, it was a desperate moment.

John Wilkes Booth grimaced in agony as he staggered around inside a tobacco barn near Port Royal, Virginia, on April 26, 1865. His accomplice, David Herold, had already surrendered to troopers of the 16th New York Cavalry surrounding the barn, but the handsome actor who had shot President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre 12 days earlier refused to give up despite the pain of a fractured leg. For Booth and his pursuers, it was a desperate moment.

Detectives Luther Baker and Everton Conger, accompanying the 16th NY, wanted to set fire to the barn to smoke out the assassin. But 1st Lt. Edward Doherty, commander of the New York detachment, was reluctant to do so, preferring to rush the barn in the morning. Then a small, wiry sergeant known as Boston Corbett came to Doherty and asked if he could enter the barn alone. The lieutenant refused, and Conger went ahead with his plan, setting fire to some hay piled against the barn’s rear. Even after flames engulfed the structure, Booth still refused to come out.

Watching him through a crack, the sergeant noticed that Booth seemed to be limping toward a door. Corbett later testified that he saw Booth aiming his carbine. “My mind was upon him attentively,” Corbett insisted, “to see that he did no harm….I took steady aim on my arm, and shot him though a large crack in the barn.” Booth pitched over, mortally wounded in the neck. He died two hours later.

Corbett’s steady aim would transform him into a celebrity—the man who had rid the world of Lincoln’s assassin. In the weeks that followed, the sergeant drew admiring crowds wherever he went. It quickly became apparent, however, that there was something odd about the Union cavalryman. Instead of signing his name when asked for his autograph, Corbett often penned lengthy passages about the Almighty. And while at first he modestly claimed that he was just a soldier doing his job during Booth’s pursuit, Corbett began telling people that God had made him “the agent of His swift retribution on the assassin of our beloved President, Abraham Lincoln.”

His strange behavior became more noticeable when he discovered the downside of his new celebrity. Many people worshipped him, but he also encountered detractors. Crank letters began arriving, some of them from Booth admirers. The volume of hate mail increased, occasionally accompanied by death threats. Corbett’s fears eventually blossomed into full-blown paranoia, and he took to pointing his gun at autograph seekers. More of his admirers began falling away as unsavory facts emerged about Lincoln’s avenger.

Drunken Hatter Mends His Ways

Thomas Corbett had been born in London in 1832, but his family emigrated to New York City when he was 7. He grew up there, becoming a hat-maker. Soon after he married, his wife died during childbirth along with their infant. Devastated, he moved to Boston and began drinking heavily. One night the drunken hatter encountered a street preacher whose message apparently filtered into his befuddled brain, instantly transforming him into a religious zealot. Corbett grew his hair long, in imitation of Jesus, and thereafter called himself “Boston,” after the city where he had been converted.

His newfound religious fervor quickly flowered into full-blown fanaticism. He upset fellow Methodists with his loud shouts of “Glory to God!” He also adopted some bizarre affectations—adding “er” to all his words in prayers and supplications, for example. “Oh Lord-er,” Corbett would yell, “Hear-er our prayer-er!”

The young hatter’s zeal reached new heights on the night of July 16, 1858, after he spied two prostitutes walking down the street. Feeling guilty that they inspired lust in him, he returned home and read Mark 19:12, which quotes Christ as saying “they have made themselves eunuchs for the Kingdom of God’s sake.” That was all Corbett needed to see. He got a pair of scissors and calmly cut an opening on his scrotum, pulled out the testes and cut them off. Unfazed, he then attended a prayer meeting and took a walk before having a hearty meal.

By the time Corbett finally sought medical help, an enormous amount of blood had collected in the swollen, blackened scrotum. The doctor drained the wound, and within a few weeks the hatter had fully recovered.

Corbett now became a part-time preacher, roaming the Boston dockyards and sermonizing burly Irish stevedores and longshoremen. Many let him know that they resented his advice. When one angry Irishman knocked him off his impromptu “pulpit” Corbett was unfazed. “You may bring all Ireland with you,” he exclaimed, “and it won’t frighten me in the least.” By this time he was having trouble holding down a job. He insisted his employers must be what he considered “godly” at all times, and he would stop working whenever he heard any cursing, then fall to his knees and pray for the offender.

Eunuch Joins the Union Army

When the Civil War broke out, Corbett was faced with a decision: Should he become a pacifist, or join the Union Army? After much prayer, he chose to become a soldier, fighting for what he had decided was the Union’s righteous cause against the traitorous South. But he would follow a formula whenever he fired on the enemy—he’d first say, “God have mercy on your souls.”

Nor surprisingly, Corbett was in hot water almost from the first day he joined the army. He became his regiment’s self-appointed moral guardian. During a review, for example, when the colonel roundly cursed the men as they stood at attention, Corbett stepped out of the ranks to reprimand his commanding officer. He spent some time in the guardhouse after that.

Another infraction nearly got the former hatter executed. When he abandoned his post one night, insisting that his enlistment was up at midnight, the army disagreed. He was quickly arrested, tried, convicted and sentenced to be shot. For a time his life hung in the balance, but in the end the Army simply expelled him.

Corbett didn’t stay a civilian for long, however, next enlisting as a trooper in the 16th New York Cavalry. He got his first real chance at combat in 1864, when his unit had a brush with Confederate raiders under John Singleton Mosby. Cut off from his comrades, Corbett continued to fight even though the odds were against him. True to form, Corbett shouted, “Amen! Glory to God!” each time his bullets found their mark. He reportedly killed seven enemies before he ran out of ammunition. Only then did he surrender.

Sent to Andersonville, Corbett later claimed, “There God was good to me, sparing my life.” He also recalled “a score of souls were converted, right on the spot where I lay for three months without any shelter.” Yet he was reduced to a near-skeleton before he was lucky enough to be released from the prison, and had to spend several weeks in a Maryland hospital before rejoining the Army as a sergeant in Company L, 16th New York Cavalry.

From God’s Avenger to Kansas Farmer

April 14, 1865, found Boston Corbett in Washington, D.C., praying that God would allow him to be an instrument of his wrath and avenge the president’s assassination. As we’ve seen, his prayer was answered. But after the novelty of his newfound fame began to wear off, the cavalry sergeant sought an early release from the Army. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton refused.

Corbett invested a lot of time trying to get his share of the reward that the government had offered for bringing Lincoln’s killer to justice. It was a slow process, complicated by the fact that others—particularly detective Luther Baker—sought to discredit the little sergeant, claiming that the 16th’s troopers had specific orders not to shoot, since the plan was to take Booth alive. Yet Baker and Conger would later testify under oath that there had been no specific orders to shoot or not shoot. Eventually the cavalryman did receive a share of the reward money, altogether $1,653.84.

He started making hats again after mustering out, but his mental problems apparently worsened. Quick to anger and increasingly paranoid, he now slept with a loaded pistol under his pillow. It was said he feared assassination, and also kept a wary eye out for Booth’s ghost.

Corbett became a full-time minister for the Camden, N.J., Siloam Methodist Episcopal Mission in 1869. But he still couldn’t seem to find any peace, so in the spring of 1878 he pulled up stakes and moved to Concordia, the county seat of Cloud County, Kan., rolling into town on a buckboard pulled by a black horse named “Billy.” Albert T. Reed, a resident who remembered Corbett’s arrival, recalled seeing “a small, insignificant looking man, with a thin, scraggly beard, and he wore an old army cap….” Reed recalled that Corbett, who had hair that “hung to his shoulders,” was armed with two pistols.

The ex-hatter filed a claim on 80 acres about seven miles south of town, where he quickly established a reputation as a recluse—though he didn’t try to conceal his identity. When word spread that he was famous, locals invited him to give a lecture on the Booth affair and his experiences at Andersonville. To everyone’s surprise he accepted. But when Corbett showed up, he refused to say a word about Booth or Andersonville, instead haranguing the crowd at length about the need to repent.

For the most part, Corbett remained aloof from his new neighbors. At first he hired four men to work his land. They planted some corn, but he himself never appeared in the fields until the evening. Eventually he gave up farming by proxy and took to raising chickens and a few head of livestock. The source of Corbett’s funds soon became a topic of speculation. He paid for everything in cash, yet he never worked, spending most of his time either wandering on the plains or holed up inside his sparsely furnished dugout, answering his mail.

He had slightly more contact with one neighbor, a Mrs. Randall who sold him milk and butter, than with anyone else. To her he confided that he wanted to be buried on his own property, and he showed her and another woman a grave he had already dug near his dugout. He also showed them a blanket, saying that he wanted to be wrapped in it when his time came. Corbett was only in his late 40s at the time and in seemingly good health, but phantom assassins clearly lurked in his troubled mind.

Then a violent incident strained relations between Corbett and his neighbors. What would be known as the “baseball incident” took place on a Sunday morning, when some local boys were playing baseball. Reading scripture while driving past in his buckboard, Corbett became incensed that his neighbors were indulging in what he saw as a “profane” game on the Sabbath. Stopping his horse, he took a pistol from his belt and shouted, “It’s wicked to play baseball on the Lord’s Day!” brandishing his weapon. The frightened youngsters and bystanders quickly scattered.

The next day a warrant was sworn out for Corbett, who was summoned to appear in the office of Concordia’s Justice of the Peace to stand trial. Practically the whole town had turned out to see the “entertainment.” Corbett showed up fully armed, though at first he seemed placid enough. But as a series of witnesses took the stand to testify about his violent outburst, the little hatter grew more grim. When the adults who had been watching the baseball game related how Corbett had pointed his pistol at them, threatening to shoot, the former hatter erupted in a torrent of vehement denials, pointing his pistol at the witnesses. “That’s a lie, lie, lie!” he shrilled. “I’ll shoot any man who says such things against me!” Ironically the fiery little man had proved the prosecution’s case against him—though nobody was prepared to sit around pondering the fine points of the law at that juncture. “I can tell you there was scattering,” a witness remembered, adding that “they trampled each other getting to the doors and windows.” Somehow the officials managed to calm Corbett, who left the office unmolested. All thought of further legal action against the former hatter was shelved. The Kansans realized he was not exactly normal, and was perhaps even insane—but still felt great sympathy for him.

Madman Goes Missing for Good

After the baseball incident, a local politician managed to get Corbett a job as a doorkeeper in the Kansas State Legislature at Topeka. It was a well-meaning gesture that ignored Corbett’s history of irrational outbursts. For a month all went well; Corbett stuck to his duties and became something of a tourist attraction, since folks were still curious to see the man who had killed John Wilkes Booth. But the hatter once again went off the rails on February 15, 1887.

There are several versions of what happened to set him off this time. According to one account, he overheard blasphemous remarks being made during a legislative session’s opening prayer. Or perhaps there was no real reason, and the personal demons he had battled for so long finally got the better of him. In any case, Corbett started running around the capitol corridors raving, waving a revolver as the legislators ran for cover. After officials subdued and examined him, he was sent to the Kansas State Insane Asylum.

Corbett’s stay there seems to have exacerbated his problems. He had hallucinations that assassins were stalking the hallways or lying in wait for him. A month into his incarceration he stole a knife and assaulted an attendant, apparently in the course of an escape attempt.

On May 26, 1888, while Corbett and others were outside exercising, the wily former cavalryman spotted a horse tethered nearby and tried again. When their attendant was momentarily distracted, Corbett galloped away. Fliers were circulated advertising his escape and warning that he was a dangerous man. A few days later a livery stable owner reported that a man had dropped off a horse, asking that the asylum be notified of its whereabouts. It was vintage Corbett—he was concerned that his horse “borrowing” might be construed as theft.

After that he sought refuge in Neodesha, Kan., at the home of Irwin DeFord, the son of Captain Harvey DeFord, who had spent time as a POW with him. The younger DeFord hid Corbett in a barn for a few days, and when the fugitive decided to move on he was given a horse, a blanket and some money—and told never to come back. Corbett readily agreed, telling DeFord that he was “heading to Mexico.” Upon leaving, he autographed DeFord’s wife’s memory book on June 1, 1888. It would be the last documented appearance of Boston Corbett.

The strange little man who had leapt to fame in 1865 now returned to obscurity. All sorts of stories followed in his wake, including sightings all over the country. Some believe that Corbett settled in the forests of Hinckley, Minn., and died in the great Hinckley fire of 1894. The truth will likely never be known.

Eric Niderost won the 2005 Army Historical Foundation Distinguished Writing Award.

Article originally published in the October 2010 issue of Civil War Times.