In the early morning hours of the first day of 1945, Allied pilots in northwest Europe might have expected to see pink elephants before they saw Nazi aircraft. Since the Normandy invasion, Royal Air Force and U.S. Army Air Forces fighters had largely driven the Luftwaffe from the skies. Poor late-December weather had hindered efforts to counter the German ground offensive in the Ardennes—the Battle of the Bulge—but with the new year dawning cold and clear, all that prevented a renewed Allied aerial assault was aircrew hangovers.

“The first hours of 1945 were spent letting in the New Year, wishing each other all the best and having a few beers,” recalled Leading Aircraftsman Desmond Shepherd, an armorer with RAF No. 137 Squadron at Eindhoven, Netherlands. “After breakfast I was crossing the runway, going toward the armory…At that moment I heard gunfire. Looking up the runway I saw what looked like a Me-262 jet go streaking above my head. This was closely followed by several Fw-190s, and coming in the other direction were several Me-109s. I threw myself down onto the grass at the side of the runway.”

Sergeant Peter Crowest, an RAF air controller at Ursel, Belgium, reported for duty at 0900 hours. “We barely had time to judge the extent of our hangovers from the ‘night before’ when we heard and saw a squadron of low-flying fighters approaching. An enquiry from my CO as to whether we were expecting Spitfires was answered when I said they were not Spitfires but Focke Wulf 190s. Moments later I was firmly gripping the ground!”

With German fighters raking his field at Knokke, Belgium, Squadron Leader G. Dickinson made an urgent call to headquarters, only to be told, “This is January 1st, old boy, not April 1st.” Then he heard, “My God, the bastards are here!” and the line went dead.

Anyone receiving the multiple reports of simultaneous attacks across northwest Europe might have thought the Luftwaffe was attacking all at once, and would very nearly have been right. It was not, however, the same Luftwaffe that had blitzed through the Low Countries in 1940. Germany had no shortage of fighter aircraft, but possessed little fuel and few veterans left to fly them. As 176-victory ace Colonel Johannes “Macky” Steinhoff put it: “We were assigned young pilots who were timid, inexperienced and scared…[and] not yet ready for combat. It was hard enough leading and keeping a large formation of experienced fighter pilots; with youngsters it was hopeless.” Colonel Günther Lützow noted, “Our young pilots survive a maximum of two or three Reich Defense missions before they’re killed.”

General of Fighters Adolf Galland had long seen the futility of battling fighters while bombers devastated German cities. He wanted to concentrate his forces beyond enemy escorts’ reach and attack the bombers all at once: a Grosser Schlag, or Great Blow. New long-range Allied fighters, however, left no place for such a blow to be struck. By October 1944, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, feeling Adolf Hitler’s wrath, blamed everything on his fighter pilots and their general in particular. “Mustangs are practically doing training flights over Bavaria,” he railed, tearing off Galland’s medals in front of all his men. “I’ll put them back on when your damned fighter pilots start shooting planes down again.”

Galland’s Great Blow was handed over to Brig. Gen. Dietrich Peltz. What Galland was to fighters, Peltz was to bombers: an experienced Junkers Ju-87 Stuka and Ju-88 ground-attack expert. Plus, at just 30 years old, he was ambitious and loyal, and obsequious where Galland was obstreperous. Instead of a Great Blow in the air, Peltz wanted to destroy Allied fighters before they ever took off. Code-named Bodenplatte (baseplate), his operation—10 Jagdgeschwader (fighter wings) attacking 16 airfields of the British Second and U.S. Ninth Tactical air forces in Holland, Belgium and France—originally was supposed to be flown in support of Hitler’s December offensive, but whenever the Ardennes sky cleared it was full of Allied fighters. The Luftwaffe had lost more than 600 aircraft and almost 350 pilots by New Year’s Eve, when a coded “go” signal went out to fighter bases across northern Germany: The Great Blow was on for the next morning. “Maintaining complete radio silence up to the moment of attack, all Geschwader will fly low over the frontier simultaneously in the early hours of the morning, to take the enemy air forces by surprise and catch them on the ground.”

Recommended for you

Timed less for enemy inebriation than sunny skies, Bodenplatte would nevertheless be remembered as the “Hangover Raid.” In contrast to the festivities on the Allied side, celebrations and alcohol were verboten that night to German pilots, who mostly went to bed early, slept if they could and rose in the wee hours. Ground crews worked all night to ready every plane. Nineteen-year-old pilot Sergeant Werner Molge never forgot his arrival at base: “When we turned in at the field, a fantastic sight spread out in front of our eyes. The aircraft of all the Staffeln had been taxied from their dispersals by the ground crews and were lined up at the field, as if for parade inspection. Fifty Fw-190D-9s in the last light of the moon.”

At this point few Germans dared to fly over formerly occupied countries in daylight, let alone before dawn; it was doubtful they could even find targets on their own. Ju-88 and Ju-188 night fighters took off first as pathfinders, dropping flares for them to follow. According to Peltz’s plan, all would arrive over their targets at the same time: 9:20 a.m.—at those latitudes in midwinter, just after dawn.

Before the sun rose on 1945 an ominous roar echoed over the Arnhem Salient. The Allies had been launching thousand- plane raids for years, but these were headed the other way: more than a thousand German fighters crossing the lines just 150 feet off the ground, beneath Allied radar. Corporal Geoffrey Coucke, a radar technician manning the top of the lighthouse on Walcheren Island in the Scheldt River, was caught completely off guard by “hordes of [German] planes flying towards the Belgian coast. They passed on both sides and many were nearer the ground than my perch. I shall always remember that grandstand view of the last major effort of the Luftwaffe.”

Such low flying, however, made the German fighters easy prey for anti-aircraft gunners on both sides. Orders had been passed to German flak crews to expect large formations of friendly aircraft, but many never got the word. Sergeant Erich Heider, flying a pathfinder Ju-88 for Jagdgeschwader 26 (JG.26), was forced to take evasive action near the Ijssel River. “This was German, our own flak!” he later exclaimed. “Only shouts of anger were our answer. What a mess, and this following several weeks of preparation. The operational plan was no good.”

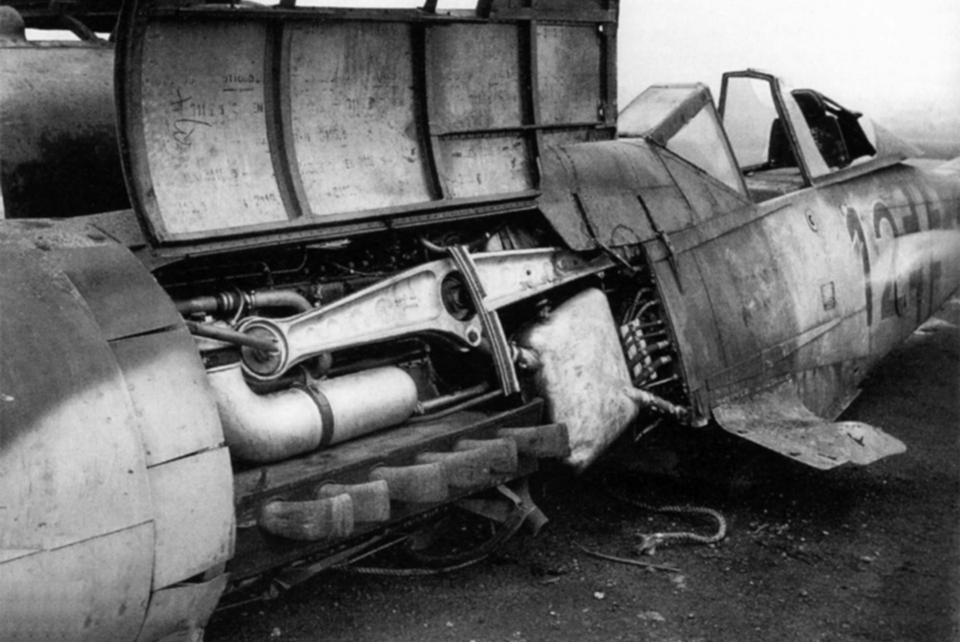

Bad planning extended to target selection as well. JG.26 split up. Half found the field at Grimbergen, Belgium, deserted; 132 Wing RAF had recently moved up to Woensdrecht, Netherlands, which escaped attack completely. The half-dozen aircraft remaining, however, were protected by a full contingent of flak crews. To destroy a few B-17s, a Lancaster, Mustang and Spitfire, JG.26 traded 21 planes and 17 pilots lost.

The rest of the wing attacked Brussels-Evere, one of the busiest fields in Belgium. Lieutenant Günther Bloemertz recalled their arrival: “Hundreds of bombers and fighters were standing drawn up on all sides of the field. Our bursts smacked into the parade. At that moment a few Spitfires were taking off—they moved right into the deadly hail, overturned, crashed or burst into flames.” Headquarters rang the Evere flight office to warn there were German fighters reported in the area. “You’re too late,” Fight Lt. Frank Morton replied. “If I stick this phone outside you’ll hear their bloody cannons!”

A sky-blue Beechcraft belonging to Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands and Air Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham’s new luxury Douglas Dakota transport came in for particular pastings. Coningham, the Second Tactical Air Force commander, arrived from Brussels to find his ride burning and most of his bleary-eyed men still returning from a night on the town. “The Air Marshal was a bit taken aback at the state of the officers and aircrew,” his driver recalled afterward. “He was not at all pleased (afterwards the rules of staying over all night were reviewed).”

Not all the Allies were as hungover as the Germans might have hoped. Many bases had already launched dawn missions, some of which were even on the return run. Flight Lieutenant R.C. Smith’s Spitfire had fuel issues; he had aborted his flight and arrived back at Eindhoven at the same time as JG.3. One against 40, Smith plunged to the attack, scoring a Messerschmitt and attacking nine others before running out of ammo. But Eindhoven’s rocket-firing Hawker Typhoons, which had run amok over German tank columns for six months, now found themselves on the receiving end. Three squadrons were taxiing for takeoff when the Germans swept in low from the southwest, with Lt. Col. Heinrich Bär, one of the war’s highest-scoring aces, in the lead. He caught a pair of “Tiffies” taking off. Flight Lieutenant Peter Wilson, on his first mission as leader of 438 Squadron, veered off the runway and climbed out to die minutes later of stomach wounds. His wingman, Flying Officer Ross Keller, barely got airborne when Bär shot him down; he was later found in the burned wreckage of his Typhoon. JG.3 destroyed almost 30 enemy planes, damaged another 30 and lost about 30 of their own. If the entire operation had gone the way of Eindhoven, Bodenplatte would have been deemed a success.

For the most part, however, the German pilots’ inexperience showed. Rather than hit and run low and fast, they popped up to circle back for more, giving AA crews a second or third go at them. Flight Lieutenant Ronnie Sheward, acting CO of 263 Squadron at Antwerp-Deurne, remembered “standing on a bank with my pilots and yelling at the Germans, ‘Weave, you stupid bastards!’ They were flying straight and level and being shot at by the ground forces….AA got 9, Mustangs 2.” Group Captain Denys Gillam of 146 Wing concurred: “If any of my boys put on a show like that I’d tear them off a strip.”

Asch, Belgium, was home to the P-47 “Hun Hunters” of the Ninth Air Force’s 366th Fighter Group and blue-nosed P-51s of the 352nd, on loan from the Eighth. The Thunderbolts were returning from a morning raid on German tanks near St. Vith when they spotted 50 inbound fighters of JG.11. First Lieutenant Melvyn Paisley of Red Flight, 390th Squadron, piloting his P-47 La Mort, downed four of them, one with an unconventional attack. “Instead of using my guns, I chose to initiate my attack with the rockets I was carrying,” he said. “I missed him with the first two, but got him with the third.” Landing, he called for his ground crew to rearm his “Jug” for another go. “The field was still under attack and they were not about to reload….My flying was over for the day.”

Lieutenant Colonel John C. Meyer’s Mustangs were scheduled for a bomber escort mission that afternoon, but he’d wangled permission for an early-morning combat air patrol and had just started his takeoff roll. “Immediately upon getting my wheels up I spotted 15-plus 190s headed toward the field from the east,” he reported. “I attacked one getting a two-second burst at 300 yards, 30-degree deflection, getting good hits on the fuselage and wing roots.” The Focke Wulf, flown by Private Gerhard Böhm, half-rolled, caught a wingtip and cartwheeled across the field. “I then selected another 190,” Meyer reported. “I attacked but periodically had to break off because of intense friendly ground fire….On the last attack the E/A [enemy aircraft] started smoking profusely and then crashed into the ground.” Meyer’s score came to 24 by war’s end.

“We had a runway-side position at the damnedest dogfight!” remembered an Asch ground crewman, one of many who gathered below to pop off a few rounds from their Colt .45s and watch the Germans pepper an abandoned Flying Fortress. “It was a hulk, had been cannibalized of everything that could be used….Nine or ten Jerries would go for the B-17 and try to get a big victory, but it had no fuel or anything to catch fire, so it just sat there and absorbed their gunfire like a large sponge!”

One of Meyer’s section leaders, Captain William T. Whisner, got a 190 immediately after takeoff, but his Mustang was hit in the wings and oil cooler. “Being over friendly territory,” he reported, “I could see no reason for landing immediately so turned toward a big dogfight.” In the melee he scored another 190 and a 109. “By this time I saw fifteen or twenty fires from crashed planes….I saw a 109 strafe the NE end of the strip. I started after him, and he turned into me. We made two head-on passes, and on the second I hit in the nose and wings. He crashed and burned east of the strip.” Four kills made “Whiz” another of the Allies’ top scorers for the day. He went on to score a total of 15½ victories in Europe and 5½ over Korea (see “The Magnificent Seven,” November 2014 issue). Altogether the Americans at Asch knocked down 32 enemy planes—40 percent of JG.11. “We hope at least one of their pilots got back to tell the story,” said 366th commander Colonel H. Norman Holt. “They’d think twice before trying it again.”

By noon Bodenplatte was finished. The surviving Germans fled in ones and twos back toward Germany, leaving smoking airfields in their wake. Results were mixed at best. Evere lost 34 aircraft destroyed, 29 damaged; Melsbroek, Belgium, 35 destroyed, nine damaged. Others, like Heesch in the Netherlands and Le Culot in Belgium, got off virtually unscathed. Altogether the Luftwaffe destroyed about 250 Allied planes and damaged 150, but lost more than 200 pilots killed or captured (including three wing commodores, five group commanders and 14 squadron leaders). Nearly half fell to flak, too much of which was their own. It can only be speculated whether Germany would have achieved more, or lost more, in Galland’s aerial Grosser Schlag. One of the Luftwaffe’s largest single-day missions, Bodenplatte was also its largest single-day loss.

Sergeant Stefan Kohl, downed by flak at Metz-Frescaty (where JG.53 suffered a 48-percent loss rate), put a brave face on things, refusing to have his photo taken by his captors until he had combed his hair and polished his boots. He spoke fluent English, and under interrogation by 386th Fighter Squadron CO Major George Brooking answered by pointing out a window at wrecked Thunderbolts smoldering on the field. “What do you think of that?”

Brooking gave his reply a few days later, before Kohl was shipped off to POW camp. A fleet of shiny new replacement P-47s had already arrived from Paris. It was as if Bodenplatte had never happened, and Brooking asked, “What do you think of that?”

“That,” the German nodded ruefully, “is what is beating us.”

For the German view of Bodenplatte, frequent contributor Don Hollway recommends Bodenplatte: The Luftwaffe’s Last Hope, by John Manhro and Ron Pütz. For the American side, try Danny S. Parker’s To Win the Winter Sky: Air War Over the Ardennes, 1944- 1945. For more photos and video, visit donhollway.com/bodenplatte.

Originally published in the March 2015 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.