It was a Monday morning in Dallas, Texas, July 28, 1913. In a small real estate office at 110 Field Street 32-year-old stenographer Florence T. Brown was alone and busy preparing for the day’s work. Fellow employee S.B. Cuthbertson had headed over to the courthouse at 8:20 a.m., leaving her in charge of the office. Within minutes a man she knew only slightly showed up. Murder, not property, was on his mind. He delivered several hammer blows to Florence’s head and then cut her throat from ear to ear with a sharp knife or razor, nearly decapitating her. Scratches and fingernail marks on her face, neck and upper torso, teeth marks on her arm and wrist and deep cuts to her fingers showed she had put up a desperate fight for her life. The killer left her body in a pool of blood and washed up in a nearby sink, leaving it full of bloody water, before making his escape into the busy street. About 8:50 a.m. Cuthbertson returned from the courthouse, but he noticed nothing wrong and sat down to begin his work. Two other employees—junior partner W.R. Styron and rentals manager G.W. Swor—soon arrived. Within a minute or two Swor discovered Brown’s body and raised the alarm.

‘Psychopaths can affect normal human emotions and morals when it benefits them. Flashing his disarming smile, Jones seemed harmless to casual observers’

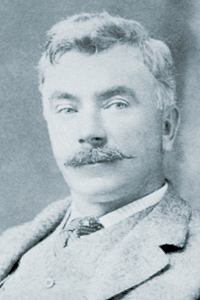

The killer was Felix Robert Jones. It was neither his first murder nor his last. But it was typical of his work, exhibiting brazen risk-taking, unspeakable brutality and cool deliberation. Records document three other murders by Jones, and there were perhaps more as yet unknown, for he was a professional killer in the mold of infamous fellow Texan James B. “Killin’ Jim” Miller. Born on March 1, 1875, on a farm along Owl Creek in southeast Coryell County, Felix had five siblings (including brother Wesley, two years his senior) and three half-siblings. He was the only badman in the family.

Thomas A. Morrison, born in 1852 on Owl Creek within 20 miles of the Jones farm, became a close associate of both paid assassin Miller, who was born in October 1861 and raised in Coryell County, and Jones. At Jones’ 1918 trial for the murder of cattle baron Thomas Lyons, Morrison testified he had known the accused all his life. Miller was 13 when Jones was born, and when Miller killed his first man in July 1884 in Coryell County, Jones was 9. Most everyone in Coryell County knew of Miller. He was a man one did not anger, as that might well be a lethal mistake, with retribution coming unexpectedly. Jones and Miller were both psychopaths, killing for convenience, revenge or money without a second thought.

There is little doubt Jones was well acquainted with Miller’s relatives, as the Joneses and the Bashams (Miller’s mother’s family) have intermarried. A third Coryell County family, the Evetts, also shares ties with the Jones and Basham families. The most notable Evetts family member, the late historian J. Evetts Haley, took a snapshot of Tom Morrison in 1931, and wrote on the back that Morrison was an old friend of the Evetts family. There is no proof Jones considered Miller (see “The Lynching of Assassin Jim Miller,” by Ellis Lindsey, in the October 2012 Wild West) a role model, but it is a possibility, and certainly Jones eventually followed in Killin’ Jim’s deadly footsteps, working closely with Miller’s partners in crime.

At age 19 Felix married Virginia “Virgie” Dixon, born in Coryell County exactly one day after Felix. In 1900, according to census records, they were living on East Leon Street in Gatesville, the Coryell County seat, with two young daughters. Felix is listed as a barber. By 1907 they had moved to Merkel, in Taylor County, where T.J. Coggin, an associate of Jim Miller, also lived. Merkel, 17 miles west of Abilene, was on the Texas & Pacific Railway, which connected Fort Worth, Dallas, El Paso and points beyond.

It was in association with Coggin that Jones began his career as a killer for hire in December 1909, some eight months after a lynch mob strung up Miller in Ada, Okla. Over an eight-year stretch Jones would kill four people, either on contract or to prevent his arrest, in each case assisted or commissioned by Miller’s former associates. Two days after his fourth murder he participated in a planning session with Morrison in Colorado City, Texas, for hits on banker Bill Johnson of Snyder, Texas, and Johnson’s son-in-law Frank A. Hamer, the Texas Ranger who later hunted down Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow. And murder wasn’t Jones’ only game. In 1915, in a further demonstration of his ruthlessness, he cold-bloodedly put fellow passengers in peril when he arranged the derailment of a train on which he was riding in order to sue the railroad company.

Here is a look at the four known murders committed by Jones.

Alf Cogdell Murder

On December 22, 1909, in Abilene, Texas, Felix Jones shot a man in an upstairs room of a building in the downtown business district. One other person was present during the shooting, T. Earl Baldwin, who didn’t actually see the seven rapid-fire shots Jones delivered to the neck and upper torso of Alf Cogdell, but he said he heard them and saw Cogdell and Jones in an argument and a struggle just before the shooting. Jones pumped all seven rounds from a .45-caliber Colt Model 1905 semiautomatic pistol into Cogdell at point-blank range. The shots rang out just after the two men left the room Baldwin was in. Jones then walked out of the building and calmly surrendered to Sheriff T.C. Weir.

T.J. Coggin bonded Jones out of jail. The next day a letter extolling Jones’ peaceful nature, signed by 26 citizens of Merkel, appeared in the Abilene Daily Reporter. Jones hired Abilene defense attorney J.F. Cunningham and pleaded self-defense. Several questionable defense witnesses testified they had heard Cogdell threaten to kill Jones the day of the shooting, though none provided a reason for the threats. One such witness was barber Gene Petty, whose name didn’t appear in reports of the killing until he testified at the trial more than three months later. According to Petty, Cogdell had told him he would take Jones’ gun away from him and beat him to death.

During the trial it came to light that Baldwin was under indictment for attempted murder in Fort Worth. Police there had possession of his .44 Colt six-shooter, and he now carried a rented .32 semiautomatic pistol. He testified he had known Jones about 18 months in Merkel and Abilene.

The prosecution asserted Jones and Baldwin had gotten Cogdell drunk and then lured him up to the office where Jones killed him. The day before, Cogdell had sold his share of the Palace of Sweets confectionery shop, and he was planning to move away from Abilene within a few days. He was carrying about $400 and the buyer’s note for $1,750 before his murder, but the cash and note were not on the body. The prosecutor suggested Jones had taken them. Considerable credible testimony supported his theory, but in Texas self-defense was a powerful legal argument if you could marshal sufficient testimony to the peaceful nature of the shooter, provide witnesses testifying to threats made by the deceased against the defendant and pack the courtroom with partisans—all signatures of Miller and Jones trials.

The trial convened in the Big Bend town of Alpine, the Brewster County seat, with a population of about 600. On the third and last morning, April 13, 1910, the courtroom was overflowing with 500 mostly partisan spectators. Jury members deliberated for 18 hours and then told the judge they were deadlocked 10-to-2. The judge sent them back to continue deliberations. They returned six hours later, at 3:30 p.m. on April 15, and delivered a verdict of not guilty.

But that wasn’t the end of the matter. In the last week of August 1912 the Taylor County grand jury in Abilene indicted Jones’ principal witness, Baldwin, for Cogdell’s murder. Authorities arrested Baldwin in Springfield, Mo., and brought him to Abilene for trial. Jones and attorney Cunningham met with the accused as soon as he arrived in town. The trial was set for September 16. Cunningham paid Baldwin’s bond and estimated the case would take no more than two days.

Just what new evidence justified Baldwin’s indictment was not reported, but the defense and the prosecution each had one new witness. The trial was delayed until March 13, 1913, and a jury returned a verdict of not guilty on March 15. No details of the arguments were published. Why Baldwin was in Missouri when indicted is not known, but, curiously, Jones was running a real estate scam in that area at the time. That ended the Alf Cogdell murder case. No one was ever convicted of the crime. Jones, the killer, was free to take on his next project, the murder of Florence Brown.

Florence Brown Murder

Sometime in 1911 Felix Jones met T.H. Vinson, a real estate trader in Abilene, and they began to collect land abstracts on west Texas properties in preparation for a planned “business” trip back East. In 1912–13 Vinson and Jones traveled to Iowa and Missouri, seeking fraudulent real estate transactions with dealers there.

Something went wrong in these transactions, and Florence Brown, a stenographer with the Robinson and Styron realty firm in downtown Dallas, came into possession of fraudulent deeds Jones had created on the company’s printed forms. Jones found out about it. Lee Starling, a Dallas attorney who knew Florence, saw her speaking with a man and woman he did not know on Main Street on the evening of July 27, 1913 (the evening before Brown’s murder). Starling interrupted their conversation to speak briefly with Florence. The couple turned their backs and feigned interest in a display window. After Starling and Brown finished their chat, Florence and the couple resumed their conversation and walked away. Starling would positively identify the man as Felix Jones after the latter’s arrest in El Paso.

The next morning, the 28th, someone entered the real estate office and brutally murdered Brown, as described earlier. The three male employees who arrived later moved the body before the police arrived, tracking blood about the office. The company vault was locked, its contents intact.

Brown’s uncle, J.D. Robinson, hired Bill McDonald, U.S. marshal for the Northern District of Texas and a former Texas Ranger captain, as a private investigator in the case. McDonald worked the case independently until the Thomas Lyons murder in 1917. His previous investigations into the crimes of Jim Miller and his ever-present associates gave him an edge over Dallas police.

Jones was a suspect early on, but when interrogated in August 1913 he told Dallas authorities he’d been in Abilene at the time of the murder and could produce at least “100 prominent citizens” to testify to that fact. The case went nowhere until October 1913 when a painter named Fetner came forward. Fetner testified that shortly before the July 28 killing Jones had told him he was going to Dallas to retrieve some documents from Brown. “I am going to get them peaceably if I can,” the painter quoted Jones as saying. “If I can’t, I’m going to get them.” Fetner also told authorities Jones had approached him just a few days before his testimony, reminded him of the earlier conversation and said, “For God’s sake, forget it!” Still, in the absence of hard evidence, no indictment was forthcoming. The case stagnated until June 1917.

After Jones’ June 1917 arrest in connection with the murder of Lyons in El Paso, Dallas authorities investigating Brown’s murder obtained a warrant to search the Fort Worth rental house at 1319 Washington Ave., where Jones had moved with his family in 1916 or early 1917. There authorities found the forged deeds in a trunk. That evidence and news that Lyons had received crushing blows to the skull with a blunt object—much in the manner of Florence Brown’s fatal wounds—brought a quick indictment of Jones by a Dallas grand jury on June 30, though the case didn’t go to trial until May 1919.

In 1918 District Attorney J. Willis Pierson interviewed Vinson in connection with the Brown murder. The transcript of his interview reveals interesting details about the real estate scam Jones was running and its connection to Brown’s murder. Vinson had been dealing in real estate in Abilene before linking up with Jones and may have been the mastermind behind the scam. Vinson testified he and Jones had traveled to Iowa and Missouri in April or May 1913, and the two of them had been jailed for a short time in Kansas City in connection with one of “the deals” they did. Still, Vinson claimed ignorance of fraud in any of the deals in which he participated. He also told Pierson he was afraid of Jones.

When asked by Pierson whom he thought had murdered Brown, Vinson replied that if Jones hadn’t done it, then he believed the killer was likely barber Gene Petty. Vinson said he had known Jones and Petty in Abilene, and Jones had tried to get him to sign Petty’s bond on a bootlegging charge there. The sheriff in Abilene had warned Vinson not to sign the bond, as Petty was a “mean fellow, and he is hard to catch.” If he signed the bond, the sheriff warned, Petty would likely flee, and Vinson would forfeit his bond. Vinson declined to sign.

Jones’ defense attorney in the Brown case was El Paso Judge L.A. Dale (who also served as Jones’ lead defense attorney in his February 1918 trial for the Lyons murder). Attorney Starling, a critical prosecution witness, was absent when the case was called for trial on May 7, 1919; he may have had a conflicting court appearance. District Attorney Pierson consequently requested dismissal of the charges against Jones. Felix and wife Virgie were ecstatic. The district attorney said he had no further plans concerning the murder, and the case was closed.

The Florence Brown killing remains one of the most egregious unsolved murders in Dallas history. U.S. Marshal McDonald had insisted his private retention by Robinson be kept secret, so his findings were not part of the official case file until Jones came up on charges four years after the crime. District attorneys had come and gone over the period, and by then there was little public pressure to convict Jones. McDonald died the month before the trial, and Jones had already been convicted of the Lyons murder and was facing a 25-year prison sentence.

Frank Battle Murder

At 9:30 p.m. on August 20, 1913, just 23 days after Florence Brown’s murder, someone waylaid Frank J. Battle in Gatesville and shot him four times with a .41-caliber revolver. The shooter had been waiting in the dark at the rear of Battle’s bakery/grocery store on the east side of the square in Gatesville. The assailant fired three shots into the victim’s back as Battle was entering through the rear door. One of the slugs exited in the center of Battle’s chest. The shooter then fired a fourth shot that grazed Battle’s forehead. About an hour later, after a doctor had given the mortally wounded storeowner pain medication, Battle told the district attorney he hadn’t seen the shooter and could think of no reason for the crime. Battle died at 4 o’clock the next morning.

An investigation revealed Felix Jones had sent a telegram from Abilene to Battle’s father-in-law on August 2, 1913, and 10 days later had sent a registered letter containing $400 from Gatesville to the Fort Worth Trading Co. Jones, who had arrived in Gatesville from Abilene 10 days to two weeks before the August 20 shooting and left two days after it, became a suspect. Coryell County Sheriff E.B. McMordie and McClennan County (Waco) Deputy Sheriff Lee Jenkins left Gatesville on the morning of August 26 after receiving a tip Jones was in Fort Worth, and they arrested him that night as he prepared to board a train. Jones was carrying a loaded .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver and an extra supply of cartridges in a grip. He refused to discuss the murder and seemed cool and self-possessed when arrested. After a grand jury indicted Jones on August 27, authorities released him on $7,500 bond. His defense attorney was again J.F. Cunningham of Abilene.

That evening W.W. Hammack, Battle’s father-in-law, was found unconscious in his front yard and died soon after. “I am a persecuted man,” his suicide note read. “I cannot stand the publicity any longer.” A coroner determined the cause of death to be strychnine poisoning. Hammack had been summoned to testify before the grand jury the next day. According to a Hammack family genealogist, the family suspects Hammack had hired the assassin Jones, as Hammack disapproved of his daughter’s marriage to Battle, an Italian and Roman Catholic.

The trial was held at the U.S. District Court in Gatesville. The ubiquitous Gene Petty was a defense witness. The jury debated for 2½ days and reported a 6-to-6 deadlock before the judge sent them back to debate some more. The jury ultimately reached a verdict of not guilty on February 16, 1914. The case was closed, and no one was ever convicted of Battle’s murder.

Although it didn’t involve murder, Jones’ callous disregard for human life was on exhibit the night of December 13, 1915, when he and accomplice W.G. Clark removed spikes and a stabilizing bar from the outer rail of the Wichita Valley Railway tracks on a curve 2 miles north of Abilene. The next morning Jones boarded the four-coach daily train at 6:30 and braced himself in the toilet of the smoking car near the engine. Just before 7 a.m. the train hit the damaged section of track. There was a 7-foot drop on the outside of the curve, and though neither of the first two coaches went off the crossties as the rail slipped outward, the intense shaking splintered the crossties like so much kindling. The last two coaches fared worse, the fourth coach coming to a stop with its back end hanging over the embankment and its front end still coupled to the coach ahead. Had the coupling failed, the last car would have overturned, almost certainly wounding or killing passengers, many of whom were women and children.

As it happened, the only person to claim injury was Jones. His plan was to sue the railway company for $50,000 in damages. The lawsuit failed, and Jones and Clark were indicted. The case against Jones was dismissed at trial in August 1918, as he had already been convicted and sentenced in the Lyons murder case. Clark, however, received a six-year sentence at the Texas State Penitentiary in Huntsville.

Thomas Lyons Murder

Felix Jones seemed untouchable when it came to getting away with murder—that is, until his 1918 conviction in the Thomas Lyons slaying netted him a 25-year prison sentence. The murder was a contract hit, arranged by T.J. Coggin and Tom Morrison and executed in El Paso on May 17, 1917. Felix had used a hammer to smash in Lyons’ skull. The case drew the largest crowd of spectators in El Paso history to date. It was all quite bizarre and complex, the conspiracy beginning in late April 1917, and the trial ending with Jones’ conviction on February 21, 1918.

The key witness in the Lyons case was none other than W.G. Clark, whose previous association with Felix was not revealed during the trial. Clark’s testimony included details of a conversation he had had with Jones, Morrison and a third man, Gee McMeans, two days after the Lyons murder, in which the men discussed plans to kill banker Bill Johnson and lawman Frank Hamer. On October 1, 1917, McMeans ambushed Hamer in Sweetwater, Texas. In the ensuing shootout Hamer, despite leg and shoulder wounds, killed his assailant.

Two El Paso newspapers published some 140 articles about the Lyons case, invariably representing Coggin and Morrison as well-to-do cattlemen, while failing to disclose their criminal history. Morrison, clearly a conspirator in the murder, was never indicted, and T.J. and brother Millard Coggin, though indicted for conspiracy, saw their cases dismissed. Jones was the only one convicted. After sentence was pronounced, a cheerful Jones remarked to a nearby reporter, “I dusted the gallows that time.” The comment has a detached, analytical quality about it, worthy of a psychopath.

The inevitable appeal, decided on June 25, 1919, failed, and on July 1 Jones was transferred from the El Paso County Jail to the Texas State Penitentiary in Huntsville. In November 1926 Texas Governor Miriam “Ma” Ferguson granted Jones a pardon, and Huntsville authorities released him. The pardon was later announced in a December 16 Associated Press article. Governor Ferguson’s explanation for the pardon was specious and inconsistent with records in the Texas State Archives. Over her two nonconsecutive terms she averaged about 100 pardons per month, ostensibly to relieve overcrowding conditions in the prisons, though she and her husband—the previous governor, who had been impeached and removed from office—were suspected of selling pardons for campaign contributions.

Jones returned to Fort Worth after his pardon and spent the next quarter-century working in real estate and as a sometime barber. Although he never again saw the inside of a prison, you can bet Frank Hamer kept him in mind as a potential suspect. Felix and Virgie bought the house at 1323 Washington Ave., next door to the house they had rented before his conviction for Lyons’ murder, and they lived out their lives there. She died on November 5, 1948, he on October 25, 1951. They are buried beside each other in Fort Worth’s Shannon Rose Hill Cemetery.

Psychopaths can affect normal human emotions and morals when it benefits them. Flashing his disarming smile, Jones seemed harmless to casual observers. His neighbors in Fort Worth were shocked in 1917 when they learned he was under indictment for murder. They told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram that while he was seldom home, “when he appeared, he always wore a genial smile and had a most pleasant address.”

In 2012 Jones’ great-grandniece Jane Evetts Cartwright told me she too was shocked to learn the truth about her ancestor. She recalled him as an avuncular, kind, smiling visitor with a sack of gumballs when she was 5 and met him at her aunt’s home in 1948. She immediately recognized him and his straw fedora, striking a pose with his siblings in a photo she found online. B.R. Jones, Felix’s great-grandnephew, was 10 years old when he heard stories about his ancestor at a family gathering in Coryell County. He later asked his grandfather, Henry Clay Jones, “Was Uncle Felix really that mean?” The answer spoke volumes: “He would have killed his mother for a dime.” WW

Originally published in the June 2015 issue of Wild West. Retired R&D physicist Jerry J. Lobdill thanks Rhonda Mohler, a relative of Felix Jones through marriage, for her assistance. See Lobdill’s Last Train to El Paso (www.LastTrain2ElPaso.com) and Triumph and Tragedy: A History of Thomas Lyons and the LCs, by Ida Foster Campbell and Alice Foster Hill.