Every culture has its trained fighting forces, and within those services are elite units that train and perform at a much higher level. In Polynesian Hawaii, the ali’i, the ruling class, had the na ali’i koa, or chiefly warriors.

To fully appreciate the role the latter played in the history of the islands, particularly with regard to their unification, one needs to understand a bit about the archipelago’s history and culture.

Historians speculate the first settlers of the Hawaiian Islands were Polynesians who arrived sometime prior to the 13th century from the Marquesas Islands, some 2,400 miles to the south across open ocean. Using the sun, stars and sea to guide them, the Marquesans made the voyage in double-hulled sailing canoes loaded with crops such as taro and breadfruit, as well as pigs and chickens. These voyagers were not just exploring but looking for new lands to settle, which meant they had to be prepared for anything.

By the early 13th century, another wave of Polynesian voyagers, this time from Tahiti, had reached the Hawaiian Islands. Landing at South Point on the Big Island of Hawaii, they soon spread across all the islands, setting up independent kingdoms on each.

The kingdoms often warred with one another, thus diminishing the chance for Hawaii to become a unified nation. It was the Tahitians who established the kapu (taboo) system, forbidding certain acts, foods, etc. in an effort to keep order. The code also established the sacred supremacy of the ali’i ruling class.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

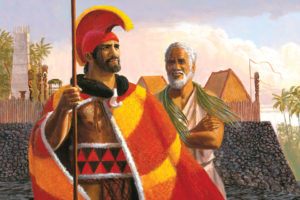

As the islands became increasingly populous, conflict erupted between the competing ali’i. The advent of the kapu system and the rise of the ali’i created a need for a specialized fighting force to protect the ali’i and act as a vanguard in actual combat. The na ali’i koa constituted a highly trained, disciplined and well-organized full-time unit of lesser ali’i, in contrast to the na koa, an army of commoners called into action during wartime.

Kamehameha, the ali’i who would unify the islands under his own rule, entered training as a na ali’i koa in the 1840s when he was 7 or 8 years old.

The training usually fell to personal tutors and included a great deal of hand-to-hand combat known as lua — a bone-breaking form of wrestling — as well as the use of an assortment of deadly handheld weapons. These included the pahoa, a long, double-edged hardwood dagger, sometimes fitted with shark’s teeth; the niho ’oki, a curved wooden knife with a single shark’s-tooth blade; and the ma’a, a sling fashioned of braided fiber from the inner bark of the hau (coastal hibiscus) tree, a coconut husk or even human hair.

Other weapons used by the na ali’i koa included the pohaku newa, a war club comprising a carved stone head lashed to a wooden handle with a fiber cord, and the ku’ia, a quarter staff about 6 feet long and sharpened at both ends. Spears were also common. Shorter versions, like the javelinlike ihe, were meant to be thrown, while longer spears, such as the pololu, were meant to be used like European pikes. The latter was very long and heavy, requiring a warrior of great strength and skill to effectively wield it. Another common weapon was the ko’i pahoa, or stone adze, employed much like the battle-axes used by the Vikings and other European warriors. Na ali’i koa later trained to use firearms. Petroglyphs at Kaloko-Honokohau National Historical Park on the Big Island include depictions of muskets alongside men. Historians believe the area likely served as a training ground for the na ali’i koa.

Kamehameha rises to power

Kamehameha was the son of Keoua, a high-ranking ali’i on the Big Island. He was born sometime around 1736, a time of constant power struggles among the archipelago’s ali’i. As Keoua died when Kamehameha was still a boy, he was raised in the court of his uncle, Kalani’ opu’u. While there, Kamehameha began training with his uncle’s na ali’i koa. He learned the skills quickly and was reportedly an expert warrior by young adulthood.

On Kalani’opu’u’s death in 1782, Kamehameha rose to prominence. Kalani’opu’u’s son Kiwala’o inherited the kingdom and gave his cousin Kamehameha control of the Waipio Valley, to the north, as well as symbolic guardianship of the Hawaiian god of war, Kuka’ilimoku. The relationship between the cousins was strained at best, and soon after the funeral, when Kamehameha made a dedication to the gods instead of paying homage to Kiwala’o, the scene was set for conflict.

That same year Kiwala’o’s half-brother Keoua Ku’ahu’ula, who had inherited no property after his father’s death, went into a jealous rage, felling coconut trees in Kamehameha’s district and killing some of his men. Adding insult to injury, Keoua offered their bodies as a sacrifice to Kiwala’o, who accepted the offering. Kamehameha had no choice but to defend his honor. Recognizing the omens, women and children from both sides fled to Pu’uhonua O Honaunau, a place of refuge on the west coast where they would be safe no matter the outcome.

The resulting Battle of Moku’ohai (a grove to the south of Kealakehua Bay) was fought on land and sea, with both ali’i fielding their na ali’i koa as shock troops in forward echelons. It was a fierce battle, and one of Kamehameha’s chief supporters, Kame’eiamoku, was among the first seriously wounded when tripped up by a pololu and stabbed. Kiwala’o saw him fall and dashed in for the kill, but before he could deliver a fatal blow, a sling stone knocked him down. The injured Kame’eiamoku then slit Kiwala’o’s throat with a shark-toothed pahoa. The king’s abrupt death left the battlefield to Kamehameha and his warriors, and they took over the northern and western districts of the Big Island. But Kamehameha set his sights far higher.

cook’s fateful visits to hawaii

Though no firearms were reportedly used at the 1782 Battle of Moku’ohai, the Hawaiian ali’i were broadly aware of European weaponry as early as 1778. That year British explorer Captain James Cook and his contingent of sailors and marines aboard HMS Resolution anchored off the coast of Kauai, becoming the first Europeans to visit the remote islands. He collectively dubbed them the Sandwich Islands, after his patron John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich (and, yes, reputed progenitor of that sandwich).

Though relations between the British sailors and Hawaiians were initially cordial, tensions quickly exacerbated. On Cook’s visit to the Big Island early the next year, Hawaiians stole one of Resolution’s launches. On Feb. 14, 1779, the 50-year-old captain led an armed landing party ashore at Kealakekua Bay in a failed attempt to seize Kalani’opu’u, Kamehameha’s royal uncle, and exchange him for the stolen boat.

As Cook sought to reboard one of the launches, indignant warriors clubbed and stabbed him to death. In the ensuing skirmishes, the British sailors and marines killed scores of islanders with musket and cannon fire.

Kamehameha witnessed much of what transpired and was intrigued by the power of the European firearms. He understood that mastering such weapons would enable him not only to defeat his enemies but also to be a deterrent to outsiders seeking to conquer the islands. In 1789, the ambitious ali’i persuaded Scottish-born fur trader Captain William Douglas, who was wintering in the islands aboard the merchantman Iphigenia, to give him muskets, ammunition and a swivel gun, ostensibly to protect the Big Island from enemies supplied with weapons by Douglas’ rivals.

Kamehameha’s desire for firearms only grew.

In 1790, American trader Simon Metcalfe, captain of the brig Eleanora, arrived off the Big Island and immediately overstayed his welcome by having Kamehameha’s trusted counselor Kame’eiamoku flogged for some offense. Moving on to Maui, Metcalf and crew soon found themselves in a more serious skirmish with islanders and used their cannons and muskets to great effect against the attackers. Meanwhile, Eleanora’s sister ship, Fair American, captained by Metcalfe’s son Thomas, dropped anchor off the Big Island. Unaware of the family ties between the captains, but having sworn revenge against the next Western ship to visit, Kame’eia-moku directed his men to attack Fair American. They killed all aboard but wounded seaman Isaac Davis, whom Kamehameha ordered into protective custody. In the wake of that incident, Kamehameha detained Eleanora’s boatswain, John Young, who had come ashore to ask after Fair American’s missing crew. Treated well, the two American sailors soon became trusted advisers and, later, ’ohana (family) through marriage to the ali’i’s family members. They also instructed Kamehameha’s warriors in the use, maintenance and repair of firearms, training that forever changed Hawaiian combat tactics.

By then, the Sandwich Islands had become a popular stop-off on the Pacific trade route between the Americas and China. Subsequent British and American traders, always eager to turn a profit, were more than willing to trade firearms and gunpowder with the Hawaiian ali’i.

Kamehameha proved even more resourceful, soon obtaining the formula to make his own gunpowder. Its ingredients—sulfur, potassium nitrate and charcoal—were plentiful in the islands, and with traders regularly bringing lead, the ali’i soon stored up all the ammunition he needed.

Though the Westerners traded freely with Kamehameha, they also provided firearms and ammunition to the other ali’i, some of whom openly opposed Kamehameha. It was the latter’s leadership and ability to earn the trust and loyalty of his people, particularly the na ali’i koa, that made him successful. The addition of Western weaponry was icing on the cake.

Kamehameha takes fight to other ali’i

After securing victory at Moku’ohai, Kamehameha began his quest to unify the islands. He first had to gain complete control of the Big Island. Between 1783 and ’90, he led repeated assaults against Keoua’s stronghold in the southern Kau district. But the latter’s forces had allied themselves with the ali’i of Maui, bolstering their ability to resist, thus in 1790 Kamehameha resolved to first subdue Maui. To do so, he had to risk fighting on two fronts. If the gamble paid off, he would win big — if not, he stood to lose everything. Leading the charge on both fronts were Kamehameha’s na ali’i koa.

With most of its best warriors deployed to Hawaii in support of Keoua, Maui was left lightly defended, and Kamehameha’s men ravaged the island. But word that Keoua was raiding his territory back on the Big Island forced Kamehameha to turn back before he could consolidate his gains.

Later that year, Kamehameha moved against Puna, in the southeastern Big Island, coming up against forces led by Keawema’uhili, an ali’i loyal to Keoua. Though both armies were equipped with firearms, the battle was mainly fought using traditional Polynesian weapons and tactics — at which Kamehameha’s na ali’i koa excelled. Kamehameha led by example, moving among his warriors and reportedly shouting, “I mua, e na poki’i, a inu ’i ka wai ’awa’awa!” (“Forward, young brothers, and drink the bitter water!”). The sight of their leader dodging spears and grappling with the enemy motivated his warriors to rally — enough to carry the day.

With Kamehameha engaged in Puna, Keoua sensed an opportunity and led an uprising. It was ultimately unsuccessful, and as Keoua retreated toward Kau, an eruption of Kilauea killed many of his men. It was a bad omen from Pele, the goddess of fire, and within months warriors allied with Kamehameha lured Keoua and his na ali’i koa into an ambush and slew them to a man.

With his rivals on the Big Island subdued or dead, Kamehameha became the undisputed ali’i nui, or high chief, of Hawaii. Contesting his efforts to subdue the remaining islands, the respective ali’i of Kauai, Maui and Oahu joined forces against him in 1791. After amassing a great fleet of war canoes, they set sail for the northwestern coast of Hawaii, where they fought Kamehameha in the Battle of the Red Mouth Gun.

It was a unique fight, both for the scale of the naval battle and the numbers of muskets and cannons used. Until that engagement, most fights at sea around Hawaii had been little more than clashes of canoes in which combatants threw or thrusted with spears. But on that day, the opponents employed canoes fitted with small, swivel-mounted guns, whose fire inflicted significant casualties and destroyed many vessels. Kamehameha watched from the deck of Fair American as his well-trained warriors — under the watchful tutelage of Young and Davis — laid waste to the enemy fleet.

The long war had taken its toll on the ali’i and warriors of all islands, and over the next four years of relative peace, the combatants licked their wounds and regained strength. During the respite, Kamehameha continued training his forces, especially the na ali’i koa, and in 1795, he was ready to resume his quest to claim sole control of the islands.

The decisive, bloodiest battle

By early 1795, Kamehameha had amassed upward of 1,000 war canoes and an army of more than 10,000 men to move against his enemies. His first objectives were Maui and Molokai, whose combined forces he defeated at the Battle of Kawela on the latter island. From there, he moved against Oahu, where he confronted the warriors of that island and Kauai.

Fought that May, the Battle of Nu’uanu was the largest and bloodiest engagement of Kamehameha’s quest to rule the islands. The armies met on the southeastern side of Oahu, near present-day Honolulu. On landing at Waialae and Waikiki, Kamehameha’s forces fought a 6-mile running battle, pushing the defenders northward into the Nu’uanu Valley. Kamehameha failed to notice his enemy had carved gun emplacements into the high ground and had been drawing the attackers into a deadly trap.

Despite heavy cannon fire from the heights, however, Kamehameha’s forces continued to press the enemy into retreat. Realizing he had to silence the enemy’s guns, Kamehameha ordered two groups of na ali’i koa to scale the cliffs of Nu’uanu Pali and get behind the guns. The elite warriors did so, surprising the enemy gunners and seizing control of the ridge. With the cannons silenced, the fighting turned to bloody hand-to-hand combat.

Through a series of skirmishes, Kamehameha’s warriors eventually forced their enemy, whose strength had dwindled to 800 men, to the razor’s edge of the pali for a last stand. Rather than be captured and face enslavement or ritual sacrifice, most defenders fought to the death, many literally being driven over the edge of the 1,000-foot cliff at their backs.

Though Kamehameha had yet to bring Kauai and Niihau under his dominion, Nu’uanu proved the deciding battle of the war. Finally, in 1810 Kaumuali’i, the last independent ruler of Kauai, relinquished control of that island and Niihau to Kamehameha, making the latter ali’i nui of all the Hawaiian Islands. His victory in the long fight for unification was due in large part to the skill, dedication and loyalty of his na ali’i koa.

U.S. Army veteran Dana Benner holds a degree in history and a master’s in heritage studies. He teaches history, political science and sociology at the university level. For further reading he recommends A Brief History of the Hawaiian People, by William De Witt Alexander, and Captive Paradise: A History of Hawaii, by James L. Haley.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.