“He didn’t have to go on the patrol, but once committed, he had a premonition that he would get killed”.

War stories, as the adage goes, are all true and all false. The survivors of one patrol had been telling a mostly false version of this story for 31 years—not deliberately, but because each man’s personal survival strategy had repressed large parts of the traumatic memory. One thing that helped unlock those memories was a celebrity’s published account of the loss of his stepson, who had been one of their teammates (see end of story for a letter written by Jimmy Stewart about the loss of his son).

When America first landed on the moon in July 1969, the world knew about it. But the previous month in Vietnam, when a U.S. Marine Corps reconnaissance patrol code-named “American Beauty” fought for its life, nobody knew the whole story of the Marines’ bravery. And none of the survivors could tell it themselves.

On June 8, 1969, those Marines were trapped in an ambush that claimed the life of actor Jimmy Stewart’s stepson, Marine 1st Lt. Ron McLean. The remaining five were pinned down for 24 hours by a dug-in NVA platoon. The resulting onslaught of automatic-weapons fire, grenades and 12 hours of close air support should have killed the team many times over.

“We all expected to die on the hill,” said Bob Lake of Aitkin, Minn., who at 19 had been the assistant patrol leader. “We were in no man’s land, unknowingly dropped into a [1,200-member] enemy battalion, and [helicopter extraction from] the hilltop was the only way out.”

The Marine Corps’ record of that patrol consists of a 29-line entry found in a July 10, 1969, command chronology. Although that history relates an account of the patrol by Major Charles W. Cobb Jr., the American Beauty survivors could not recognize their experience in his narrative. For the military, perhaps it was just another patrol that went bad. Recon, with a 40 percent casualty rate, is dangerous business.

In January 1998, I tracked down Bob Lake, a Minnesota high school teacher, who had been one of the recon team members who walked out of the DMZ with me 29 years earlier. Lake provided the names of Roger See, Joe “Doc” Sheriff, Jimmy Sessums and Bunn, the Vietnamese Montagnard scout. The patrol leader, See, was the most difficult to locate, as he was living a nearly underground existence.

According to Sheriff, of Booneville, Ky., who had been the patrol corpsman: “Roger’s cool and even-headedness kept us alive. This was my first patrol. I thought, ‘God! If this is what it’s like out here, what are my chances of surviving?’” Sheriff went on to do 14 more recon patrols, with no casualties.

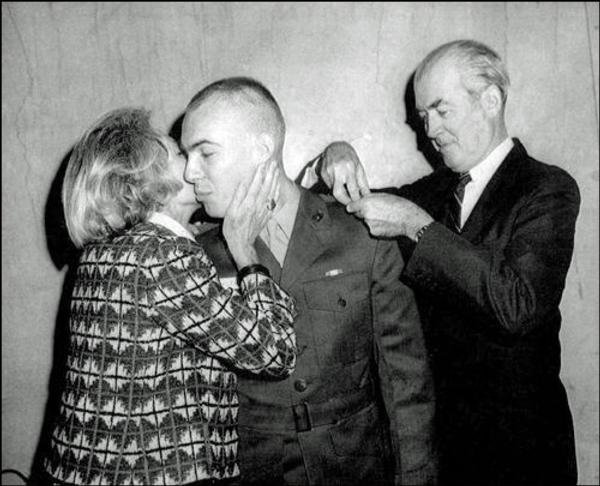

Lieutenant McLean had had infantry experience but had only been in recon a couple of weeks before he was killed. Officers seldom went on recon patrols, and this would be McLean’s first. Navy Lieutenant Martin Glasser was the battalion surgeon for the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion in June 1969. He said that because he and Lieutenant McLean, 24, were both from California, they quickly became friends.

Glasser, now a medical director with a managed-care organization in Phoenix, Ariz., remembered that an order had come down from division headquarters to have recon teams inserted into the DMZ to confirm enemy presence there. He also recalled that a priority for the mission was to bring back a POW. He said it was already known that there was an NVA battalion there, and the recon commander, a lieutenant colonel, refused the order, realizing that to drop lightly armed teams in the middle of it would be suicidal. That battalion commander, according to Glasser, was replaced by another who carried out the order.

Glasser said that McLean had heard the same intelligence briefings and was well aware that DMZ patrolling would be highly risky. He wasn’t going to ask his men to do something he wouldn’t do himself. “He didn’t have to go on the patrol,” Glasser said, “but once committed, he had a premonition that he would get killed.”

In reconnaissance units the person with the most experience is the team leader, and that was Corporal See. McLean, although an officer, accompanied the team as another rifleman. “I was not comfortable with McLean on the patrol,” said See. “He didn’t know his way around yet. I didn’t want to go into the DMZ with another new guy.”

Sessums, Lake and Sheriff each recalled the premonition that McLean had voiced in the first days of the patrol. “I didn’t even know he was Stewart’s son,” said Sheriff. “I’m a 19-year-old corpsman and this lieutenant is seeing himself getting killed. I wasn’t prepared for that or anything else that happened.”

The team went in early on June 6 with orders to patrol an area four kilometers square. Two other reconnaissance teams were given similar missions, and all three would be operating in parallel quadrants across the DMZ. After a 35-minute helicopter flight from Quang Tri in northern I Corps, American Beauty was dropped on the same hilltop they would later fight on with every bit of firepower they had to save themselves. To allow the helicopter landing, American jets had blown away the hilltop foliage, and it was still smoldering when the team went in.

The NVA had to have seen the helicopter insertion. As the Marines raced into the jungle, the enemy had occupied the landing zone and dug in. The NVA had 54 hours to fortify their position. Late that afternoon the team observed a bunker complex with NVA soldiers periodically poking their heads out of holes. American Beauty, from an undetected observation point, called in 72 rounds of artillery.

By June 7, a day before American Beauty had its own fight, the recon team to the east had had an eyeball-to-eyeball encounter with the NVA, reporting two dead and several wounded. Four helicopters were shot down attempting their rescue.

“We were monitoring their radio frequency,” said Lake, “and could hear all the gunfire, and suddenly their radio went dead. Our fear factor shot off the scale. We thought they were wiped out.” (In fact, the reason American Beauty lost contact at that point was that the other team changed its radio frequency.)

“I knew from what was happening to [the recon unit to the east] that this was going to happen to us if we didn’t get out of there,” said See. “I spent all day on the radio trying to get us out before it happened.”

“Request denied,” came the reply. “Continue mission.”

The patrol spent the second night on a mountain precipice to minimize its exposure. “I had my feet wrapped around a tree so I wouldn’t roll off when I was sleeping,” said Lake. “We had movement 20 meters from where we were.”

Late on the morning of June 8 the team had moved only a short distance from its night position. “We had movement all around us,” said See, “and I was slowly moving us in the direction of the hilltop.”

Sessums remembered McLean being the rear security and recalled that every time he came forward he was reporting movement. “Were we watching them or they watching us? I don’t know,” said Sessums.

The official chronology records that at 1130 hours on June 8 the team fired on approaching enemy troops with unknown results. Team members deny that happened, saying that up to that point their position had not been compromised. The team still did not have permission to move to the LZ, but See headed that way, figuring that orders would have to come. For four hours they zigzagged through the bush, stopping frequently to listen. At about 1630 they stopped to eat, hoping to receive word that they were to be pulled out.

They were sitting slightly off a trail with the men back-to-back, observing, listening and ready to eat. Lake remembered Corporal See looking back to the east, the direction he thought any attack would come from. “We were stupid being right on the trail,” said Lake.

“We were bewildered. We knew there were [NVA] all around us.”

They had no way of avoiding what came next. “I’d just opened a can of meatballs and spaghetti,” said Lake, “and as I looked in the direction we were headed, I saw two jungle hats coming down the trail. They were only 15 meters away. I shot four rounds and…the whole team opened up….We killed one and wounded the other.”

Sessums, of Paragould, Ark., radioed back that they had a POW. “The POW was our ticket out,” said Lake. “With the POW our mission was over. The helicopters were on their way.”

But now they had the prospect of NVA coming at them from two sides. If not for the prisoner, the team could have gone into hiding to wait for a safer time to move. Having secured the POW, however, they were radioed their orders to get to the landing zone. A Marine observation aircraft was in the area, and the pilot monitored the team’s frequency. He radioed, “Be advised you are being attacked from the west.”

The team suddenly had to lay down a defense for what the pilot estimated was a platoon-size unit. Corporal See ordered the patrol to get on line and quickly string together Claymore mines. Expecting to be overrun, Sheriff and Lake did little more than stretch out their arms to place the Claymores facing the attackers.

“The Claymores were no more than six feet ahead of me when the observation pilot called to let it rip,” said Lake. “Both Doc and myself were blown through the air by the back blast.”

By this time there were fixed-wing aircraft overhead, and the area was raked with bombs. Sheriff remembered the jets and helicopter gunships pounding the hill for more than an hour while the team waited for its green light to move out. “This hilltop was only 30 yards wide and 20 across. We didn’t expect anything could survive the bombing.”

The team moved out with the hilltop as its objective. As the Marines came off the trail and into a clearing at about 1745, the LZ was to the left. The hill had about a 35-degree grade that made distance visibility nearly impossible. The Montagnard scout Bunn was up the hill first, followed by Lake and Sheriff. Sessums, McLean and See provided cover from behind a fallen tree.

“I was with the prisoner, trying to get him to move uphill,” said See, “when the NVA opened up, and a bullet got me in the leg. McLean moved over to help with the bandage.” McLean was sitting up when machine gun fire erupted, and a round caught him in the chest.

See yelled for Doc Sheriff. As Sheriff ran down, the NVA positions exploded with automatic-weapons fire. Bullets were right at Sheriff’s heels, and a dust cloud engulfed him as he reached McLean. Sheriff’s running to McLean remained Sessums’ most vivid memory: “Bullets came from everywhere. He should have been killed.”

Reaching the body, Sheriff declared McLean dead. This was Roger See’s second tour in Vietnam, and as the leader of more than 60 patrols, he had not lost a team member. McLean was his first.

The patrol had walked into a beehive, and now the prisoner was a handicap. There was no way they could move forward with him. Sessums and Sheriff watched as See took aim at the prisoner’s head and shot him.

Years later, See remained troubled about killing the prisoner. “I should have tied him up,” he said. “That was my mistake.”

See told Sheriff to get back uphill. “I was going up the hill hunched low,” said Sheriff. “I was one foot from a hole where an NVA was curled up. If he had been able to get his AK-47 aimed lower, he would’ve had me. But because his weapon was elevated, all the rounds went into the air and the muzzle blast threw me back, leaving burn marks on my face.”

Startled, Sheriff fired his own unaimed automatic volley. Sessums, watching from below, assumed Sheriff had been killed and radioed back that they now had two KIA. That transmission was negated when Sheriff signaled he was okay. With their POW dead, McLean dead, and Bunn, Lake and Sheriff on the hillside, See and Sessums left McLean’s body and moved ahead.

Sheriff knew that the guy with the AK-47 was still in his hole. Both Sheriff and See believed this was the one who had killed McLean. Sheriff motioned to See to throw a grenade. Standing above the hole, See pulled the pin and waited several seconds before dropping the grenade. The blast neutralized that threat, but the other dug-in NVA soldiers kept the Marines pinned to the ground.

Each of the Marines had a story of an enemy grenade that didn’t go off. Which were the same story told through another’s eyes and which were individual incidents can’t be discerned, but while it was still daylight, one landed just feet from See’s head. “I told myself ‘I’m a goner,’” he said, “but the grenade didn’t go off.”

“We were told to get to the top—secure the high ground,” said Lake. “This is crazy, but Doc and I started singing ‘From the Halls of Montezuma.’ I grabbed a grenade and tried to throw it uphill, but my backpack interfered with the throw and it only went about 10 meters before rolling down, exploding very close to Doc Sheriff. He yelled, ‘What the f— are you doing?’”

The team had no way of estimating enemy strength. The treeless hillside was clear only to the north. Had there been any NVA in the distant tree line, they could have picked off the exposed Marines one at a time. McLean’s body was 35 meters behind them.

The Marines had been unable to move for 21⁄2 hours. On top of the hill was an A-frame bunker, reinforced with logs and dirt and with sightlines to anything that approached the top. “The jets started dropping 100-pound bombs on top of that thing,” said Lake. Helicopters also hammered the hill with machine guns. “They knocked the crap out of everything, but apparently not the bunker,” he said.

Sheriff, who earlier had escaped the short grenade toss of Lake, now caught a piece of shrapnel in his hand. Shrapnel also blew a hole in the plastic stock of his M-16 rifle. The NVA were in their holes, not returning fire.

Late that day 1st Lt. Frank Cuddy, a Marine helicopter pilot who was later awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his support of American Beauty, was flying back from Laos with his helicopter gunship team when he saw the McDonnell F-4 Phantoms and learned that a recon team was in real trouble.

The aerial observer was short of fuel and wanted Cuddy to take charge. At 1930, believing the pounding air support had neutralized the hilltop, they attempted a helicopter extraction. Cuddy’s team would supply covering fire for the Boeing-Vertol CH-46s that would try to lift the team out.

“As the choppers approached we were ready to make our run,” said Lake. “But as they came to hover, the NVA opened up and forced them off.”

Cuddy’s two Bell UH-1 Huey gunships remained on station while new teams of CH-46 pilots made two more extraction attempts. Each time, the NVA delivered crushing fire. The helicopters limped back to Vandegrift combat base.

“We carried enough fuel to stay on station for two hours,” said Cuddy. “When we left to refuel and rearm it was dark, and we would be leaving [American Beauty] all alone. I promised them I’d be back.”

As darkness fell, the team had been able to crawl together behind some fallen trees where they could take cover. “The NVA didn’t know where we were,” said Lake, “and they didn’t come out of their holes to look. Nothing moved.”

Sessums remembered hearing the distinct thud of a metal object hitting the tree they were behind, and then a sulfurlike smell and a hissing sound. Another dud NVA grenade. In the dark, moonless night, a Lockheed AC-130 dropped illumination flares. When a gunship did arrive, the pilot needed the exact location of American Beauty before he could deliver his ordnance.

“We carried a strobe light,” said See. “I put it in a hat and threw it away from us…the NVA tossed a bunch of chicoms at it. We took a compass reading to the strobe light to mark our position and gave it to the pilot. His machine guns started smoking.”

“The trees sounded like a chain saw was chewing them up,” said Sessums.

Cuddy thought that after this pounding the CH-46s would attempt another rescue, but he learned that the division commander had ordered a cessation of rescue attempts. Too many helicopters had already been hit. Ground forces would be used instead.

And yet, there was an honored tradition to consider. “In the Marine Corps it’s ingrained that you don’t leave dead and wounded,” said Cuddy. “To leave them out there was to let them die.”

Cuddy’s team returned on station with a plan to get the patrol out. Huey gunships carried about 1,600 pounds of fuel. Cuddy intended to get the fuel down to 200 pounds, just enough for the 20-minute flight to Vandegrift. The crews jettisoned tool boxes and extra machine-gun barrels to gain more lift capacity. Stripped down, they thought they could carry two men on one helicopter and three on the other.

“The NVA knew our plan,” said Cuddy. “They kept their heads down as we shot up our ammo….We thought maybe we got them all.” At about 0130—and against orders—Cuddy came in for the extraction. An illumination flare was dropped, and the team was told to be ready.

“I was no more than three, four feet off the ground,” said Cuddy, “when all of a sudden 15 to 20 NVA were out of their holes firing at us. We were blinded by the muzzle flashes. One came right out of the A-frame and was face to face with me, firing. I stuck my M-16 out the helicopter and emptied a magazine on full automatic.”

Lance Corporal Lake, who would have been first on Cuddy’s helicopter, saw it all. “If [the NVA] had been on our side he would have been awarded the Medal of Honor for his bravery,” said Lake. “Nothing got him.”

The co-pilot got hit and Cuddy was wounded in the face and leg. Plexiglas, shrapnel and bullets exploded in the cockpit. They had to break off the rescue attempt. Cuddy could barely control the aircraft. His radio was shot out and the hydraulic system partially shut down, but he kept it flying and landed at Vandegrift. The next day he counted 16 holes in his helicopter’s nose and cockpit area.

When Cuddy and his crews left the DMZ early on the morning of June 9, all the patrol had was the artillery battery firing illumination. The sounds of foot movement, groaning wounded NVA and bodies being dragged through the brush continued throughout the following night.

“I had been operating on adrenaline up to that point,” said Sheriff, “but now was the first time I really felt afraid. I remember saying to [See], ‘We’re not going to make it,’ and he came back, ‘Ah, Doc don’t worry, I’ve been through this stuff dozens of times, we’ll be fine.’ He was the toughest rascal I’ve ever met.”

If the aerial rescue had been successful, McLean’s body would have been left behind. Retrieving it would have required another recon insert or ground unit operation, with its own problematic consequences.

The illumination rounds were the first indication to the infantry company, four miles to the south, that an American unit was in trouble. Sometime that evening the company learned that it would move out at first light to get the team out. Bravo Company, 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, made it to the southern boundary of the DMZ around 0930, having traveled about three miles with some 90 troops. I was an artillery forward observer with that company. At a clearing 300 meters inside the DMZ, we established a patrol base. The plan was for the 3rd Platoon to make the rescue while the 1st and 2nd platoons remained in reserve.

In normal operations we avoided the trails, but in this case the terrain dictated we use them. Otherwise we would have easily added half a day to get to American Beauty. The NVA knew we were coming, and we never expected them to let us walk in. What we didn’t know was the size of the NVA force American Beauty had encountered. Two infantry platoons should have been sent in, one as a blocking force.

At 1100, Bravo Company came across a dead NVA, probably the one shot by the team the previous day. We were now walking into the battlefield. This sight caused the column to move more slowly. The point squad pulled into a clearing at about 1130. The first sight was McLean’s body sitting up, slightly hunched forward, behind a fallen tree. There was no movement.

The recon team expected the NVA to still be dug in on the hill, and See remembered trying to signal the Marines with a mirror, to let them know they were friendlies and to get them to be quiet. The first squad drew no enemy fire, and for the first time the recon team got up and moved around. Apparently the NVA had used the cover of night to make their exit. The collective guard came down, and survival instincts quickly subsided.

“When the Marines came in, I just started shaking,” said Lake. “I started crying. My team members were looking at one another, thinking, ‘Oh, boy, we are really tough sons of bitches.’”

The sun was high and the day already hot when we finished burying three NVA. It was humane of us to bury their dead, but risky to spend any more time exposed. McLean’s 200-pound body was rigged with two ponchos and a 12-foot wooden pole for a four-man carry. The grunts made the reconners carry their own.

The trail we came in on would have been the easiest way out, but now tactical wisdom argued for avoiding it. Instead we headed directly south through deep jungle mountain ravines. Pointmen used machetes to cut trail the entire 2,700-meter distance. By nightfall we had traveled only 1,000 meters and reached a dried stream bed where we set up our night position.

On June 10 we cut, climbed and carried our way for 16 hours before getting to the southern edge of the DMZ and joining with the rest of Bravo Company. It was dark when the helicopter came to transport McLean’s body. The following morning the American Beauty survivors, all with bullet or shrapnel wounds, walked back to Bravo’s original patrol base for their ride out.

Besides McLean, two other reconners from the team to the east were killed and at least 15 Marines were wounded in their efforts to verify NVA activity in the DMZ. Within two days the team was dissolved and designated “combat inoperative,” due to combat stress. Lake was sent to scuba school in the Philippines and Sheriff to another unit. Sessums and See later got paired together at a mountaintop radio relay station. The four have never been together since January 1998, when I began researching the patrol, there have been many phone conversations between the members. In addition, Bob Lake has met personally with each of the team members and Joe Sheriff has met with Roger See.“I saw Roger in the summer of 2000 in the Florida Keys,” said Sheriff, who was then 52. “Back then [in 1969] Roger was…keeping the rest of us alive. Last visit, I felt like I was able to help him.”

For his actions on the American Beauty patrol, See was awarded the Navy Cross. Both Sessums and Sheriff were awarded the Bronze Star, and McLean the Silver Star posthumously. All earned the Purple Heart. Bob Lake’s Purple Heart was only approved by the Marine Corps on April 4, 2001, and was presented to him on Memorial Day before a hometown crowd.

Bob Lake remembered his anxiety about Vietnam surfacing in February 1985, after he read an article in Good Housekeeping in which Jimmy Stewart was interviewed about his stepson’s death in Vietnam. Lake’s sense from the article was that Stewart really didn’t know what had happened, so he wrote the family a letter. In order to do that, Lake had to get in touch with a memory he had been repressing. His letter to the Stewart family drew the following response, whose brevity spoke to how privately the family had dealt with their loss.

March 19, 1985

Dear Robert Lake,

My wife Gloria and I wanted you to know that we are grateful to you for your kind and thoughtful letter. We are so grateful to you for telling us about our son, who died in Vietnam. To tell you the truth, you are the only Marine who served directly with our son that we have heard from….

Best wishes,

James Stewart

Jeffrey Grosscup was a Marine Corps artillery officer with the infantry company that rescued the American Beauty reconnaissance team. For additional reading, see: Never Without Heroes, by Lawrence C. Vetter Jr.; and First Recon—Second to None, by Paul R. Young.

Jimmy Stewart had his own close call in Vietnam, during the last bombing mission of his career. Click here to read the article.