The vast open seas and multitude of small islands over which World War II was fought in the Pacific Ocean made both sides unwilling to rely exclusively on land-based or even carrier-based aircraft. Consequently, the Pacific War saw the last widespread use of floatplanes and flying boats, which could operate from lagoons and sheltered bays where airfields might not be within easy reach.

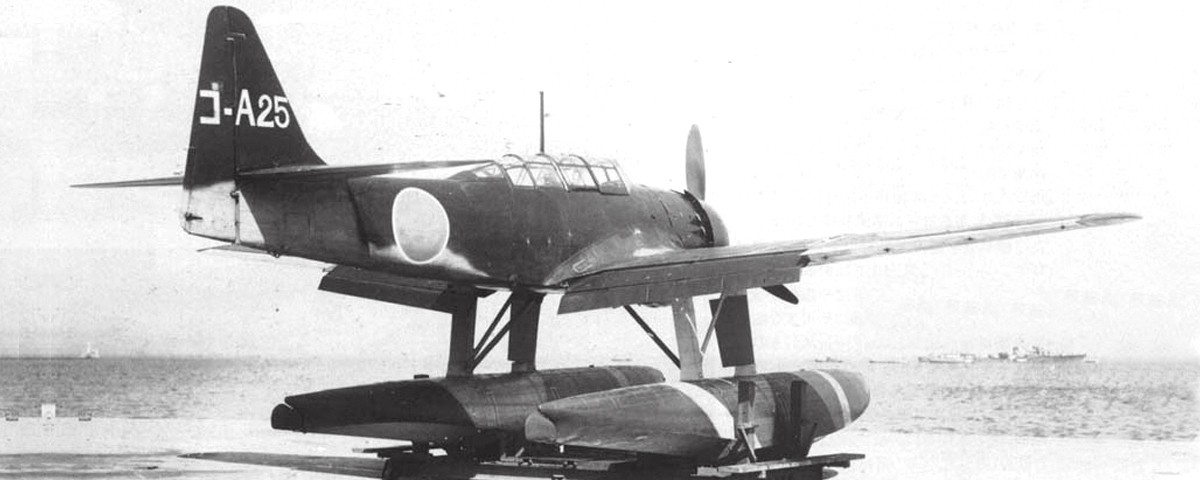

Of all the combatants, Japan made the most imaginative use of its waterborne air assets. Its Kawanishi H8K2 (code -named “Emily” by the Allies) was among the best flying boats of the war. The fast, long-range Aichi E13A1 (“Jake”) became a scouting mainstay for the Imperial fleet. The shorter-range Mitsubishi F1M2 (“Pete”) two-seat biplane was sometimes flown as aggressively as a fighter. The Japanese even produced a floatplane version of Mitsubishi’s famed Zero fighter, the Nakajima A6M2-N (“Rufe”), as well as a floatplane fighter built from scratch, the Kawanishi N1K1 (“Rex”). The Yokosuka E14Y1 (“Glen”) could be flown from submarines, and at the end of the war a submarine-launched floatplane bomber, the unique Aichi M6A1 Seiran, was slated to attack the Panama Canal.

With so many specialized roles assigned to an aircraft type that most other countries used only for reconnaissance and bombing targets of opportunity, it’s not surprising the Japanese developed a floatplane dive bomber. And it should also come as no surprise that Aichi, designer of the superb E13A1 floatplane and D3A1 “Val” carrier-based dive bomber, was responsible for its development.

The E13A1 had barely been accepted for production in 1940 when Aichi’s design team began work on a successor that October, under the company designation AM-22. As with its predecessor, this would be a twin-float monoplane, but sturdier, more powerful, faster and longer ranged. The E13A1’s puny defensive armament of one rear-mounted 7.7mm machine gun would be increased, with two 7.7mm Type 97 machine guns in the wings and a 7.7mm Type 92 weapon for the observer. With a view to the more aggressive role envisioned for the AM-22, hydraulically operated dive brakes were installed in the front float support struts, making it capable of dive bombing.

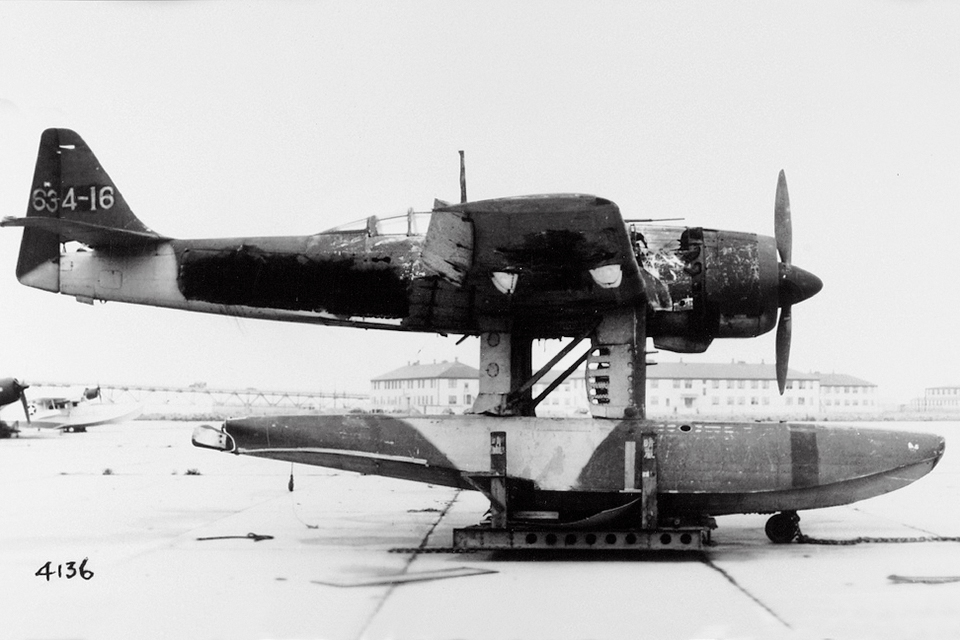

The Japanese navy, reflecting its satisfaction with the E13A1, drew up a new specification based on Aichi’s design early in 1941. Work proceeded apace, and in May 1942 the first of three prototypes made its maiden test flight. At that point, the AM-22 hit its first snag when its test pilot reported instability in flight and buffeting from the dive brakes. It took the Aichi team 15 months of redesigning to resolve those problems, but in August 1943 the navy finally accepted the plane for production as the E16A1 reconnaissance seaplane Model 11, nicknamed Zuiun, or “auspicious cloud.” The Allies code-named it “Paul.”

The E16A1 was all metal, save for the tail-plane and wingtips, which were made of wood, and fabric-covered control surfaces. In addition to the strut-mounted dive brakes— which were solid on early aircraft but perforated with multiple holes or quintuple slots in later models—the wings had conventional Fowler-type trailing-edge flaps and could be folded for shipboard storage. Each of the single-step floats featured a rudder.

The prototypes and early production Zuiuns were powered by a Mitsubishi MK8A Kinsei 51 14-cylinder, twin-row radial air-cooled engine, with a takeoff rating of 1,300 hp, driving a three-bladed, constant-speed metal propeller. The MH8D Kinsei 54 powered later production aircraft.

The E16A1’s secondary dive bomber role inspired Aichi to significantly upgrade the armament on production aircraft to two wing-mounted 20mm Type 99 cannons and a 13mm Type 2 machine gun for the observer. It could carry up to 250 kilograms (551 pounds) of bombs or depth charges under the wings. In spite of its improved ordnance and overall superior performance to that of the E13A1, veteran crews complained that the E16A1 was harder to fly and more fatiguing to handle than its predecessor, which they still preferred.

Aichi built 193 E16A1s at its Eitoku factory between January 1944 and August 1945, and an additional 59 were built by Nipon Hikoki K.K. at Tomioka from August 1944 to the end of the war. That grand total of 256 E16As (counting the three prototypes and a single experimental E16A2, powered by a 1,560-hp MK8P Kinsei 62 engine), compared with the 1,418 E13A1s built, showed how priorities for Japan’s increasingly beleaguered air industry were changing as the war turned against it.

Among the first units allotted E16A1s were the Yokosuka and 634th Kokutais (air groups). Formed on May 1, 1944, and commanded by Captain Takahisa Amagai, the 634th was attached to the Third Air Fleet and had a total of 130 aircraft, of which 24 were E16A1s. By then, however, the floatplane’s shipboard use had become as problematic as its dive brakes.

In an attempt to make up for the six aircraft carriers they had lost in 1942, the Japanese supplemented the new ones they were building by converting two seaplane tenders into light carriers and, in an even more drastic move, installing flight decks on the sterns of the battleships Ise and Hyuga. The latter, sometimes called “hermaphrodite battleships,” were intended to carry Yokosuka D4Y2 Suisei land-based dive bombers (Allied code-name “Judy”) and E16A1 Zuiuns. Both plane types would be catapult-launched, and after they had carried out their missions, the Suisei crews would fly to the nearest island air base or ditch and be rescued by accompanying destroyers. The Zuiuns, on the other hand, could land on the water and be retrieved by the battleships’ cranes. At least that was the theory.

But the October 23-26, 1944, Battle of Leyte Gulf ended in a crushing defeat that cost the Japanese 24 major warships. Thereafter, the 634th Kokutai flew its E16A1s from Cavite in the Philippines.

One Zuiun crew that distinguished itself at that time consisted of pilot Heijiro Miyamoto and observer Hiroshi Nakajima. The latter was awarded a rare medal for distinguished service while carrying out night bombing attacks on American-occupied Tacloban airfield on November 22 and 23. When the Japanese cruisers Ashigara and Oyodo, three destroyers and three escort vessels made a hitand-run attack on the American beachhead at Mindoro on the night of December 26, Miyamoto shot down a Fifth Air Force night fighter over San José airfield and bombed four patrol torpedo boats, damaging PT-77. He followed that exploit by damaging a medium transport with a 250-kilogram bomb on the 30th. For the most part, though, the E16A1’s effectiveness was limited by the air superiority the Americans had established over Leyte, and attrition was high. On January 8, 1945, what remained of the 634th was withdrawn from the Philippines and reorganized as a float reconnaissance unit.

As the Allies closed in on the Home Islands, and especially after the Americans landed at Okinawa on April 1, 1945, a desperate Japan found a new use for its Zuiuns. In this role their dive brakes were irrelevant, since kamikaze pilots were not expected to pull out of their dives. Even with a 273-mph speed and 20mm cannon armament, however, the float-encumbered suicide planes had scant chance of reaching the U.S. Fifth Fleet if they encountered defending fighters or the wall of anti-aircraft fire thrown up by the ships themselves. The only ace known to include a Paul in his score, Lt. j.g. Robert J. Humphrey of the carrier Hornet’s VF-17, was flying a Grumman F6F-5N night fighter when he spotted and shot down the floatplane 20 miles northwest of Tokumo Shima at 7:45 p.m. on May 24.

Heijiro Miyamoto of the 634th Kokutai continued to distinguish himself over Okinawa, being cited for dropping two 60- kilogram bombs on a “battleship” on March 29 (more likely the assault transport Wyandot, which suffered minor damage), hitting a destroyer with a 250-kg bomb on April 20 and sinking a transport on May 20. No Allied loss matches the destroyer Miyamoto claimed to have sunk on May 30, but during the attack anti-aircraft fire badly wounded his observer, Nakajima. Miyamoto’s own luck finally ran out on June 26, when his E16A1 failed to return from a patrol in the Okinawa area.

When not being expended on futile suicide missions, Zuiuns of the Yokosuka Kokutai served in the training role. Few Pauls remained when Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945, and although some were evaluated by the victorious Allies, none are known to exist intact today. In spite of its hopeful name, the cloud under which the Zuiun flew was less than auspicious.

Originally published in the November 2008 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.