FRANK D. HURLBUT |

| Lacking the two years of college necessary for an officer’s commission, Staff Sgt. Hurlbut received the special rank of flight officer. |

At 20, Frank D. Hurlbut became an ace in a war theater where the odds were heavily stacked against him. Frequently outnumbered by attacking enemy aircraft deep in their own territory, Hurlbut and other Lockheed P-38 Lightning pilots had as their first priority the protection of Allied bombers on missions to North Africa, Italy and Sicily in 1943. They had to remain with the bombers at all costs. Enemy aircraft could dive down from out of the sun and easily select a tail-end Charlie, a damaged aircraft or any unwary victim as a target.

In those circumstances, survival seemed chancy, a victory unlikely and becoming an ace downright miraculous. Yet Hurlbut’s final score was nine victories, one probable and four damaged in 50 missions. He became the second-highest ranking ace in the 82nd Fighter Group and the third ranking American ace in the North African theater of World War II. Mary Lou Colbert Neale recently interviewed Hurlbut for Aviation History Magazine.

Aviation History: I understand that you became an ace before you were 21. You must have had an early start.

Hurlbut: Actually I became an ace 10 days before my 21st birthday, during the invasion of Sicily. But yes, I did go into the service early. I joined the Utah National Guard at 17, serving in the 145th Field Artillery with the 40th Division for two years. That unit was federalized after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, but I was later able to transfer to the Army Air Forces as an aviation student, thus achieving my lifelong dream of flying. I graduated from Luke Air Force Base in Arizona, class of 42-H, as a staff sergeant pilot.

AH: Weren’t all graduating cadet pilots commissioned as officers?

Hurlbut: In those days you had to have two years of college to obtain the rank of second lieutenant out of cadet school. Not many had two years of college at my age, especially after being frozen by the federalization of the National Guard at age 19. Several of us held enlisted rank after we completed our three months of fighter training in a Bell P-39 Airacobra at Del Mabrey Field in Florida. We were sent to England in December 1942 aboard the liner Queen Mary. They decided to give us the rank of flight officers while we were in England. It confused everyone a bit, but it became even more confusing when we landed in North Africa shortly afterward before being commissioned. There was a shortage of pilots, and we had insisted we were eager for combat, so we were shipped out by convoy to Oran. But no one there seemed to know what to do with us or where we should be billeted, since we weren’t officers. We wandered around like lost souls, not getting any assignments. We named ourselves the ‘Sixty-seven Sad Sacks’ and had a sorrowful-looking cartoon logo made for our flying jackets. We were finally gathered up and flown to Casablanca in five Douglas C-47s to an abandoned airstrip that had a few buildings around it, making it a fighter plane and pilot pool base. All of the unassigned pilots and various aircraft–P-39s, Curtiss P-40 Warhawks and P-38 Lightnings–plus any trucks, jeeps, office equipment, beds and bedding that we found ‘loose’ at the shipping docks or needing a home, so to speak, were quickly assimilated into our unit. We had some rather beat-up planes and equipment, but at last we had a base. Before long, I joined the P-38-equipped 82nd Fighter Group and got going.

AH: I guess they were glad to have an experienced pilot.

Hurlbut: Experienced? Not really. The only fighter I had flown was the single-engine P-39, which had a tricycle landing gear. But they needed pilots so badly that they gave me a quick 28-hour twin-engine familiarization course. By April I was with the battle-seasoned 96th Fighter Squadron, flying the P-38.

AH: The P-38 was a great airplane.

Hurlbut: What an aircraft! It could take rough handling, so it could outmaneuver almost anything. And there were two engines to bring you home.

FRANK D. HURLBUT |

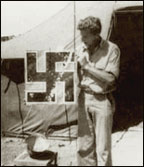

| Hurlbut shows off a souvenir cut from the tail of a downed Focke Wulf Fw-190, the same aircraft type he claimed for his second victory. |

AH: What type of missions were you assigned at that point?

Hurlbut: Our missions then were primarily long-range, low-level sorties escorting North American B-25s into enemy controlled areas of Italy, Sicily and Sardinia. We also were sent on search-and-destroy fighter missions, and we had to dive-bomb anti-aircraft emplacements, shipping and ports as well. When I first started combat in April 1943, it was really not unusual for our underequipped and understaffed unit to be flying with only 12 to 20 P-38s and be hit by more than 30 to 100 enemy fighters. Our losses were inescapable, but the enemy’s were even greater. The 82nd finally became the top P-38 fighter group in the European theater, with more than 500 enemy victories confirmed.

AH: What kind of mission were you flying when you had your first victory?

Hurlbut: It was a search-and-destroy mission on April 11. Intelligence had informed us that the Germans were trying to evacuate key personnel from Rommel’s retreating Africa Korps. So we were flying a sweep over the Mediterranean, looking for enemy transports. What intelligence did not know was that those big trimotor Junkers, the Ju-52/3ms, were heavily armed. We found the ‘Auntie Ju’ transports, as the Luftwaffe had nicknamed them, and got a big surprise. Not only was there a big cannon mounted on top of the aircraft’s fuselage just ahead of the tail, but from every porthole machine guns popped up and started firing. Our flight leader got one Ju-52 before going down. I got one and damaged another, but my own P-38 was heavily damaged. I had to return on one engine. I crash-landed at my base.

AH: Sounds like you had your hands full that day. Can you tell us more about what happened?

Hurlbut: Well, it took place late in the afternoon on a very foggy day. I was flying as the wingman to flight leader Lieutenant Bill ‘Hut-sut’ Rawson. He spotted them and said, ‘Let’s go get ’em!’ I remember dropping my tanks and flying through the Ju-52 formation, maintaining my No. 2 position and firing as we went. We were being fired on by the 20mm cannon gunners on top, and fire was also pouring at us from the side ports. Hut-sut set one on fire, and we pulled up and banked around for a second pass. While we were into it, he suddenly slowed down and fell behind me, his port engine pouring smoke. I had to continue my pass. I was hit several times. After pulling up, I saw that he had disappeared. My left engine was blowing smoke, so I feathered it. There was a cannon hole right under my left elbow, but I had not been injured. My right aileron was jammed in the up position, but that made it easier to fly level as I limped back toward Africa a few feet above the water. I saw that five or six Ju-52s were down there by then.

AH: And the record states that one was yours.

Hurlbut: Yes, Rawson and I each had one confirmed. We had damaged others. Our flight was the only one of our five flights to attack. Originally the other four had turned left, following the squadron leader. Well, it turned out that he had not seen the enemy, and his radio was out. When they realized that he was heading for home, they came back to try to join us in the attack. But it was too late. The fight was over. It was extremely foggy down near the water and getting dark, so it was hard to keep track of anyone. I found myself heading south alone. Gradually I was joined by others who fell in behind me. Like the blind leading the blind, I led them right into the well-fortified port of Bizerte, Tunisia, which was held by the Germans. Needless to say, they quickly abandoned my leadership. I hastily followed them.

AH: Did you make it to the base before crash-landing?

Hurlbut: Yes. But I ran into another problem. As I was making my straight-in approach, wheels and flaps down, fully committed at about 160 mph, two P-40s taxied out on the single runway and took off right as I was about to touch down. I pulled the gear up and gave it a try, but the P-38 continued to settle. So off the end of the strip I went, into a pool of water. Not exactly a heroic finish. However, the 82nd had done a great job on the April 11 mission and was now on its way to being the indisputable top-scoring fighter group in the Mediterranean, with 170 P-38 victories, thanks to our 96th action on that day. We were known as the ‘Fighting Jackrabbit’ squadron.

AH: Which could soon boast of having the two top-scoring aces in the entire 82nd, Lieutenant William ‘Dixie’ Sloan and Flying Officer Frank Hurlbut.

Hurlbut: Eventually, yes, but it took a while. There were a lot of missions that were limited to protecting the bombers, so pursuing an enemy fighter was not a choice. Plus the odds were never on our side, so often it was not advisable to tangle for too long. A favorite German tactic was to attack, do a split ‘S’–in which you invert the airplane and dive to recover level flight going in the opposite direction–and then depart. The first pilot would be followed by a replacement who repeated the same maneuver. They never seemed to run out of aircraft. I recall one briefing when the intelligence officer said, ‘Today you are lucky. Yesterday there were close to 800 enemy fighters out there. Today on this mission in the area of Rome not more than 450 will be flying.’

AH: Referring to the official list, I see that you had one Focke Wulf Fw-190 victory and a Messerschmitt Me-109 damaged on May 20, and an Italian Macchi M.C.202 damaged on May 24. Then on June 18 you were credited with an Me-109 and an Italian Reggiane Re.2001 destroyed and an Me-109 probable. That represents a lot of action to only bring your total victories up to four. Couldn’t some of those damaged planes or the probable have been judged as victories if there had been a follow-up verification?

Hurlbut: Quite possibly. But as I said, we fighter pilots were very busy in all the confusion and not free to pursue damaged aircraft. We rarely witnessed what others had finally done. This was in the days before the camera installation. I recall once when the 16 of us were jumped from above by 30 enemy planes–German 109s, some Italian M.C.202s and an Re.2001. We were circling at about 10,000 feet, waiting for our B-25 bombers to complete their run. The enemy came down on us time and again. I used up all of my .50-caliber ammunition and burned out four gun barrels in the fight.

AH: That must have been the June 18 mission when you got the Reggiane, your ace-making fifth. Then there was your ‘big day,’ covering the Allied invasion of Sicily, on July 10, 1943. What happened on that occasion?

Hurlbut: We were in a 20-minute fight, but I got two within the first five or six minutes. It was during the afternoon of invasion day. We had flown from our temporary base in Tripoli, joining the British to conduct a fighter sweep over the western end of Sicily, with the goal of keeping the enemy planes away from the invasion area. We could see hundreds of the invasion ships, with their tiny landing barges racing back and forth to the beaches. We flew over the Palermo area and found that we had the air to ourselves, so we circled around waiting for the enemy to show up. We didn’t have to wait long. Formations of Focke Wulfs began to take to the air from their bases around Palermo. They climbed to our altitude and the fight began. When the first Fw-190 banked in front of me, it was so close that I hardly had to use my gunsight. I set it on fire and saw it circle down to the left, but I did not have time to see it crash. Enemy fighters were all over the place, and I gave my attention to them, needless to say. Suddenly a Lufbery Circle developed. It was made up of German Focke Wulfs and American Lightnings in a single file, swinging around in a left banking turn, first climbing and then descending. Everyone was firing at the enemy in front of him, all at the same time. I was closing to the inside of an Fw-190 that was climbing. Right behind me was another P-38. But he had a Focke Wulf on his tail, who had a P-38 on his tail. It was like we were all playing follow-the-leader. I was very close to the Fw-190 and hit him with three quick bursts. He went over on one wing into a spin and crashed. All this time I had been worried about the friendly P-38 on my tail who was being pursued by the second Focke Wulf. I think I was the only one lucky enough to have the guy behind me on the same side. I recall that I would fire, then look back and yell over the radio to my friend to watch out for the fighter on his tail. But apparently that German plane was damaged, because he soon dropped out. Then we both went over to another area to look for more action.

AH: Obviously you found it. You were credited with those three victories and one damaged that day.

Hurlbut: I found my third one while coming down in a dive. I looked down and saw him skipping along close to the water, heading for Sicily. There was a P-38 chasing him from some distance back, but the German was pulling away. I had plenty of speed, so I dived down between them. My first burst got him, and he crashed into the sea. Another Fw-190 cut across in front of me from the right. I led him and fired, hitting him as he flew through my fire. But he kept on going. I claimed him as a damaged. Then we hung around for a while, but the enemy didn’t seem to want to play anymore. So we flew home. I only claimed the two planes I had seen crash, but I got credit for the first one, as other pilots in our group had seen it go down.

AH: Were any other missions as action-packed as that one?

Hurlbut: Well, that one was memorable all right, but the roughest battle of all my 50 missions was the one on September 2, 1943. It is indelibly printed in my memory, as I imagine it is for everyone who participated. I can even rattle off many of the statistics. They were repeated often enough at the time because of our winning the Presidential Unit Citation. What a mission! Seventy-four P-38s took off from Grumbalia, five returning early. We were flying cover for 72 B-25s. Twenty-four P-38s plus two spares from the 96th Fighter Squadron, furnishing top cover, were attacked by 30 enemy aircraft at 16,000 feet. The fight continued down to 6,000 feet. Several of the 95th squadron, covering the rear, flew in to assist the 96th, and an even larger fight started in at 2,000 feet, continuing down to the deck. It went on nonstop. No sooner did we think the fight was over than an additional 30 enemy aircraft dropped their belly fuel tanks and bored into the fray. At least 60 Me-109s, many M.C.202s, Fw-190s and Re.2001s were attacking us continually. Rocket projectiles were fired, bombs dropped, and you could see the puff and flash of cannons being fired every 100 yards or so. The enemy was composed of some of the finest fighter pilots Hermann Göring had to throw at us. Some aircraft had the painted yellow nose of the famous ‘Yo-Yo boys.’ They were German aces who we called that because of their bobbing up-and-down tactics. So we knew we were in for one heck of a battle. They came at us singly, in twos, and four abreast in a line. Or they went into Lufberys over our heads, then peeled down to attack–sometimes head-on, either as a single or as two together. This continuous reinforcement of fresh Me-109s with belly tanks not even dropped was something we had not seen before. They were easily running us out of fuel and ammunition. Since we were flying top cover, we ended up behind and to the rear after the bombers had completed their runs and were heading for the deck and home. We fought our way down to the water so they couldn’t hit us from below–only from the sides, rear and above. That gave us a little less to worry about. Suddenly I saw two Me-109s close astern of me dive down and pull up to the right. I broke into them after they came down only to find that I had been’suckered in’ away from my flight, which was continuing around to the left just above the water. Immediately the two attacked me from above. They were flying in line abreast and closing in. I could see their guns flashing when I looked back and up through the canopy. They were trying to box me in and get me farther away from the other P-38 formations. At this same time two new Me-109s, flying close together and firing as they came, were closing in from a 90-degree position directly above my canopy. There I was, with four enemy aircraft right on top of me and the water below, which was churning with cannon and machine-gun fire.

AH: How did you get out of that situation?

Hurlbut: Luck–luck and help from a friend. One thing I had learned and used in combat many times was to go into a violent banking maneuver by cross-controlling the aileron and rudder and even standing on the rudder while racking the aircraft into a turn. This causes the plane to slide sideways, flying in a somewhat different flight path from the direction it appears to be going. Such a rough technique saved me once again here, because I made it home. When I finally did I learned that, when I had broken to the right as the first two had suckered me away from the formation, a single Me-109 had come down from above and was right on my tail. One of my fellow pilots had literally blown him up, thus saving my aircraft and certainly, at that altitude, me.

AH: Sounds like one rough day, all right.

Hurlbut: There’s more. As I was trying to rejoin the other P-38s, another single Me-109 down at my level banked around to the left. He cut directly in front of me. I straightened out my aircraft and led him with my guns. As I started firing, he flew right through my line of fire and then simply peeled over and went into the sea. I was never sure whether he had gone in because of my fire or if he had been confused in the heat of battle and forgotten his altitude. It was chaos for everyone. It was definitely the most frustrating fight I had ever been in. Every time I started to fire at an enemy I had to stop right there to break into another aircraft because it was starting to shoot at me. I was breaking left and right continuously to fend off attacks, so it was extremely difficult to make any progress toward getting back home. This was soon going to make me run out of gas and ammunition. We had planned on a maximum of only 15 minutes of fuel consumption for fighting, and we had been in this mess about 80 miles southeast of Ischia for about 30 minutes. It was easy to trace our battle because every 1,000 to 2,000 yards an aircraft would go crashing down into the sea. I had never seen so many airplanes in the water at one time. When we did get home, I was very sad to learn that 10 pilots of our group–seven from my own squadron–had been lost. Most of those men were new to combat.

AH: Do you think the new men were extra nervous–and therefore more vulnerable?

Hurlbut: No, actually it could have meant they weren’t nervous enough. Better yet, call it unwary. There is usually, in the beginning, too much concentration on following practiced tactics. We had a saying that your chances of survival were better after six fights. The newcomer is so intent on staying in close formation as ordered that he fails to look around enough. With experience, you learn to be jittery. I was so often tail-end Charlie that I felt it when the enemy approached from the rear. Or maybe I just was always expecting him.

AH: Was it like a constant jitteriness?

Hurlbut: Well, I was always on alert. But I actually enjoyed it. I was too busy in a fight to be afraid. And although it grieved me deeply to lose a friend, I had that ‘it can’t happen to me’ philosophy. As mentioned, I was very young at the time. And dumb, as I would say now.

AH: After your 50 missions you went home. Were you ready to be out of the war?

Hurlbut: I wanted to go back for another 50 missions, but they ruled it out because I had a case of malaria that kept recurring. So I had to stay in the States and teach combat flying. I was shot down by a mosquito!

This article was written by Mary Lou Colbert Neale, a former Women’s Airforce Service Pilot who flew her share of P-38s, writes from Newhall, Calif. For additional reading, try: The Army Air Forces in World War II: Men and Planes, Volume VI, edited by W.F. Craven and J.L. Cate; and Adorimini (‘Up and at ‘Em!’): A History of the 82nd Fighter Group in World War II, by Steve Blake with John Stanaway.

This article was originally published in the January 2001 issue of Aviation History.

For more great articles to subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!