Since locating RMS Titanic on September 1, 1985, Dr. Robert Ballard has pinpointed the wrecks of the feared German battleship Bismarck, the American carrier USS Yorktown (lost at Midway) and Lieutenant John F. Kennedy’s PT-109. On his more than 120 expeditions, Ballard has explored the likes of Lusitania and Titanic’s sister ship Britannic; discovered primitive life on hydrothermal vents along the Galápagos Rift; and developed dozens of technological advances to help man explore the deep ocean. Less well known is his distinguished 30-year off-and-on career as a Cold War officer in the U.S. Navy, during which he honed the concept of underwater terrain warfare and pressed for advanced submarine technology. His relationship with the Navy would both inspire and enable Ballard’s storied career.

What risks face today’s submariners?

If you look at [commanders of] today’s fast-attack subs, and back to the Cold War, they think of themselves as fighter pilots. But they’re not fighter pilots. I always called them “blimp operators,” which they never liked. They’re operating at very low speeds with minimal maneuverability. And they’re extremely vulnerable to technology advances.

Recommended for you

So you suggested terrain warfare?

Right. An object in free open water doesn’t stand a chance in future warfare. Whereas an asset that’s involved in the bottom terrain can use that terrain to its tactical and strategic advantage.

How does multibeam sonar factor in?

Multibeam is a mapping sonar that gives you a complete three-dimensional characterization of the bottom. Maps of the battlefield of tomorrow.

What is the battlefield of tomorrow?

Imagine a battlefield of mountainous terrain and a choke point— the gap between Iceland, Greenland and Norway. That’s got a tremendous mountain range in it. It’s in a bedrock terrain. It’s in a reverberating chamber. It’s in highly magnetic rock. It’s got places to hide. You involve a submarine in there, good luck finding it.

Can subs operate in such rugged terrain?

The closest asset the Navy had was NR-1, which they’re going to lay up next year. So they’re actually, to me, going backward. NR-1 can dive to 3,000 feet. It’s the deepest diving nuclear submarine the Navy has. It has wheels—it can roll on the bottom. It has windows. Most subs avoid the bottom at all costs, whereas NR-1 can envelop itself in the terrain.

Does any sub match up to NR-1?

We did a series of studies with a group of naval officers up at MIT on a sub called NR-X—a tactically involved nuclear submarine that could enter the terrain, but had weapons systems, which the present NR-1 does not. NR-1 is a research submarine. The idea is that you would have a submarine that could be deployed to the battlefield.

How would that work?

In our scenario, we were taking a ballistic submarine that was coming off-line and turning it into a support platform for these terrain-involved submarines. Transporting them to and installing them in the battlefield—forward deploy. And then we would resupply them with the deep submergence rescue vehicles Avalon and Mystic and have them change out crews on NR-X. It wouldn’t need to be brought home.

Wouldn’t it be vulnerable on its own?

Submariners hate active sonar, but not if it’s not on ’em. NR-X goes in, lays cables and puts active sonars on the peaks like radar installations. It puts in captor mines. But instead of captor mines that are windup toys, you wire it and it becomes a SAM site. The submarine’s hidden, and you have to cross through this battlefield to get to it. Before you ever get near it, it’s going to pick you up with active and passive sonars, and it’s going to kill you with a captor mine.

What has been the Navy’s reaction to your proposals?

It was always interesting, because I was trained [in the ROTC] as an Army officer. I was trained in terrain analysis. I was a geologist. I was a tank commander. You don’t go into the battlefield without battle maps. You take the high ground. So when I came into the Navy, I tried to apply that mind-set and went on my sword. We still haven’t won that victory.

Yet the Navy funded your expedition to search for Titanic?

Well, the Navy knew I was looking for Titanic, but they wanted me to do two other missions: mapping Scorpion and Thresher.

Why revisit two sunken Cold War nuclear subs?

The Navy at the time was looking at disposing of nuclear containment vessels in the ocean. And the concern was, well, what would be the environmental impact of nuclear containment vessels if you placed them in a marine environment? They said: “Well, heck, we’ve got two submarines down there that are far worse than what we’re thinking of putting down there. They have reactors, and in the case of Scorpion, weapons. What have they done to the environment?” They first needed us to find the subs—show them where all the pieces were.

What did you find?

Both reactors scrammed and went into the bottom at high speed and are in sealed craters. They went in at impact when the ship fragmented. The reactor compartments are just very heavy objects, the heaviest. Both sites are deep-sea muds, and they drove into the bottom and closed the door.

Do they pose any hazard?

No. Researchers captured fish that were living in the wreckage and looked at their uptake of radioisotopes and their lipids. They measured and sampled, and there was very, very low-level background radiation.

In his book Scorpion Down, Ed Offley suggests a Soviet sub killed Scorpion.

There are all sorts of suppositions—that it was a hot run, that it was a battery explosion. I do not know the findings. I just collected the raw data and created the base maps, then they went in to the “fault” work…and did not share the results with me [laughs].

What did you learn on that mission?

How objects disintegrate and create debris trails. The heavy objects fall on a straight trajectory to the bottom, the lighter objects are carried as they fall.Just like separating the wheat from the chaff. Throw it all up in the air. The wind catches the light stuff, blows it away, and the kernels fall to the ground.

How did that help you find Titanic?

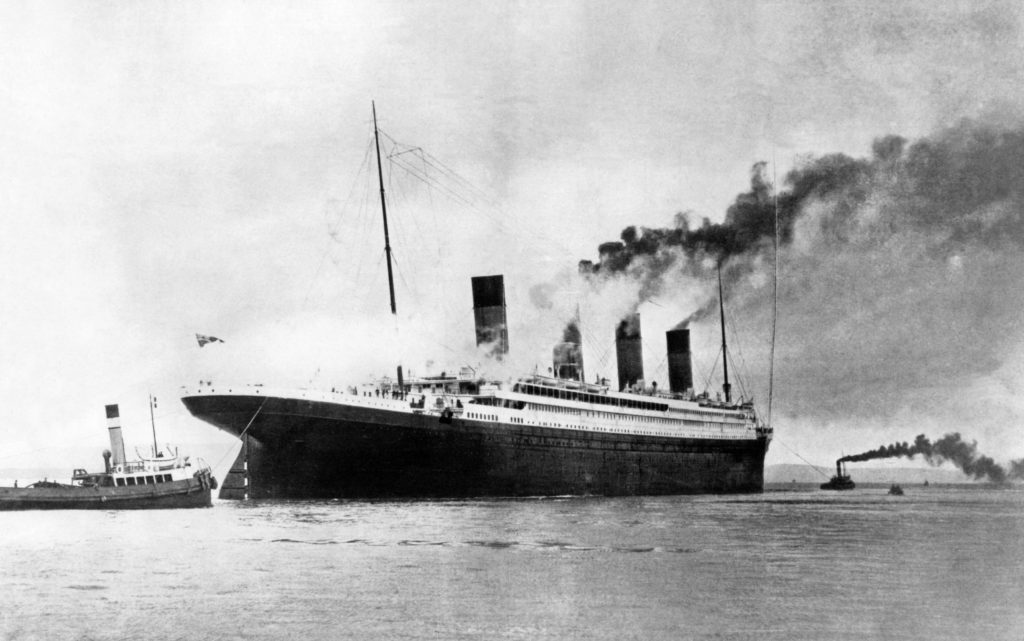

In 150 square miles of terrain, you can hide a lot of Titanics so sonars can’t see them. The other people who tried to find Titanic—Scripps, Lamont, the French—all failed using that approach. That’s when I said: “Well, let’s not look for Titanic. Let’s look for the debris.” The other guys had months. We found it on the eighth day. Picked up the debris field and then walked it in.

What was the mood aboard ship?

It was a very complex emotion. We had to be somber and respectful, but we were also happy. It was like winning the war, then looking at the battlefield the next day.

What prompted you to search for other wrecks?

Titanic was the first Pyramid of the Deep, and I wanted to go to other ones. So I did. I found Bismarck, and the swastikas were still on the deck. I went to Yorktown, and the name was still on the stern. I became amazed at the state of preservation— that the deep sea was a giant museum.

So why do you object to the retrieval of marine artifacts?

It’s silly to bring something out of the ocean. Historical context is more important. You don’t take belt buckles off Arizona. You don’t go to Gettysburg with a shovel. Access them. Visit them. In my lifetime, you’ll go into the den and the walls will come on. Ultimately you’ll be in a circular room, a miniature OMNIMAX theater in your house, and you will dial up and rent a robot from Hertz.

Do you plan to retire, or will you just drop from your horse in battle like Genghis Khan?

Just drop dead at the console…but not yet.

Originally published in the September 2007 issue of Military History. To subscribe, click here.