David Rodes and Norman Wenger step out of Wenger’s red Ford Explorer to look at an old farmhouse in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. “At the time of the Civil War, this place was owned by Abraham Heatwole,” Rodes says. “And he had a wife named Magdalenah and she was a pretty sassy lady.”

Rodes knows about Magdalenah’s sassiness because she was his great-great-great-grandmother and he grew up hearing stories about her. “She was always saying, ‘I told you so,’ ” he says. “And one day Abe came in and told her, ‘Maddy, the cow ate the millstone.’ And she said, ‘I told you she’d do that.’ And then she realized she’d been had.” He laughs. “That’s the kind of person she was.”

Rodes heard many family stories about Abe and Magdalenah, but he never heard that they smuggled draft dodgers and deserters out of the Confederacy through a secret pro-Union movement operating in Virginia during the Civil War. He didn’t learn about that until he and Wenger began researching their family histories at the National Archives and discovered, to their amazement, that they both had ancestors who were activists in the movement.

“My sympathies were altogether on the side of the Union from beginning to end,” Abraham Heatwole testified in one of the documents that Rodes and Wenger discovered. “My house was a sort of rendezvous for refugees and deserters from the rebel army making their escape from the Confederacy.”

“He kept at our house a great many refugees and helped them to escape,” Magdalenah Heatwole said in another document. “We were in constant danger from having so many come to our place for concealment and refuge while getting ready to go north.”

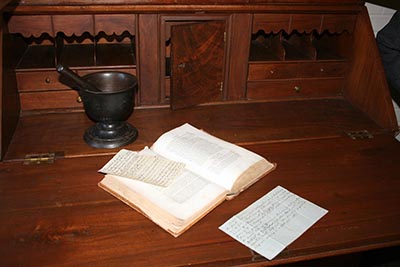

Now, standing in front of the Heatwole house, Norman Wenger flips through the pages of a book—one of the six volumes of documents that he and Rodes have published about the Unionist underground. He reads from the deposition of Abe’s brother-in-law, John Rodes: “His house was a kind of depot for refugees and deserters. He had a very good place for concealing them where they could not be found. It was one of the terminals of the Underground R.R., which was the means of conducting several thousand persons from the Confederacy during the war.”

Several thousand persons. When Rodes and Wenger read that, they realized they’d stumbled upon a story that was far bigger than family history. They’d discovered proof of a secret Virginia-based, pro-Union movement previously unknown even to Civil War historians.

“We started this to find out about our families,” Rodes says, “And then we started seeing this overall pattern about an underground railroad.”

“Family stories never mentioned that,” Wenger says, “but the documents prove it.”

Their search began in 1998, when Rodes and Wenger—who both grew up in Mennonite families in Rockingham County, Va.—read a slim volume called Mennonites in the Confederacy and spotted footnotes that hinted at untold stories about their ancestors. “There was a footnote in there about my great-grandfather Jacob Wenger,” says Wenger. “It quoted one of his neighbors testifying to his loyalty to the Union: ‘He seemed to rejoice at the approach of the Union Army and said we ought to go roasting turkeys for them.’ That caught my eye.”

Their search began in 1998, when Rodes and Wenger—who both grew up in Mennonite families in Rockingham County, Va.—read a slim volume called Mennonites in the Confederacy and spotted footnotes that hinted at untold stories about their ancestors. “There was a footnote in there about my great-grandfather Jacob Wenger,” says Wenger. “It quoted one of his neighbors testifying to his loyalty to the Union: ‘He seemed to rejoice at the approach of the Union Army and said we ought to go roasting turkeys for them.’ That caught my eye.”

Rodes noticed a footnote that quoted his great-great-great-grandmother, Fannie Bowman Rodes. “I’m going to use the language that she used, OK?” he says as he tells the story. “She quoted what the Confederates said about her family. She said, ‘They said we were lower than n——s.’ That caught my eye. To be lower than slaves—to be lower than property! Property had some value. We had no value.”

Intrigued by those footnotes, Wenger and Rodes decided to do more research. Neither man is a professional historian—Rodes, now 60, runs a gift shop and Wenger, 61, is the general manager of a farmers cooperative—but their curiosity propelled their search. The footnotes quoted documents from the Southern Claims Commission, so Wenger and Rodes traveled to the National Archives in Washington, D.C., to search through the commission’s records.

The Southern Claims Commission was established in 1871 to judge petitions filed by Southerners asking to be paid for their property—usually crops or livestock—that had allegedly been seized by Federal soldiers during the Civil War. Before paying any claim, the commission required that claimants prove two things—that they had remained loyal to the Union and that the U.S. Army had confiscated their property. Both propositions were difficult to prove, and consequently most of the 22,000 claims were denied. But every recorded claim, whether approved or not, illuminates what life was like for civilians in Civil War battle zones. “Sometimes we’d have tears in our eyes as we read those claims,” Rodes recalls.

First, Wenger and Rodes searched for claims filed by their ancestors, but they soon decided to dig up every claim filed by residents of Rockingham County. There were plenty of them because the county is located in the heart of the Shenandoah Valley—the breadbasket of the Confederacy—and General Phil Sheridan’s Union army systematically plundered and burned the Valley’s crops in the fall of 1864 in an effort to starve Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army.

During their 15 or 20 trips to the Archives, Wenger and Rodes photocopied 298 claims from Rockingham County—more than 12,000 pages of documents, some containing tales of murder, betrayal, hatred and heroism. Fascinated by the stories, they decided to publish all of the claims. Between 2003 and 2012—aided by grants from local historical groups and the expertise of Dr. Emmert F. Bittinger, a sociology professor at Bridgewater College in Virginia—they published the documents in the six-volume series Unionists and the Civil War Experience in the Shenandoah Valley. “Our mission was to preserve these documents,” Wenger says. “We haven’t made any money. It’s a labor of love.”

But not everyone in the Valley shares that love. Some folks don’t want to hear about local people who supported the Union during what they sometimes call “the War of Northern Aggression.”

“When Volume 1 came out, we gave a talk on our research and got a real chilly reception,” Wenger recalls. “I made the comment that if you were a third- or fourth-generation native of Rockingham County, chances are you had a relative who was a Unionist. And a guy got up and said, ‘I really resent that remark!’ ”

“And we found out later that one of his ancestors was involved in the underground railroad,” Rodes adds, smiling. “I called him to tell him that but he wouldn’t accept it.”

“I did all I could to assist refugees and deserters from the rebel army to escape from the Confederacy,” a farmer named John Brunk told the claims commission in 1875. “I am a Mennonite and had charge of a Mennonite church near my place where I concealed them.”

Roughly two-thirds of the claims uncovered by Rodes and Wenger were filed by Mennonites or by members of the Church of the Brethren, also known as “Dunkers.” These pacifist Christian sects opposed slavery, and their members—most of them farmers of German descent—were appalled at the South’s rush to secession after Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860.

“Secession means war; and war means tears and ashes and blood,” Elder John Kline, the leader of the Brethren in Rockingham County, wrote in his diary on January 1, 1861. “It means bonds and imprisonment and perhaps even death to many in our beloved Brotherhood, who I have the confidence to believe, will die rather than disobey God by taking up arms.”

Elder Kline’s ominous predictions soon proved true. On May 23, Virginia held a referendum to decide if the state should secede from the Union. The Rockingham Register urged a unanimous vote for secession, and local rebels visited the farms of Mennonites and Brethren to demand their support. “The day before the election, two men came to my place from Harrisonburg,” John Brunk testified, “and while talking about the election said if I voted for the Union I would be hung—and if I did not vote, I would be driven from the county and my property confiscated.”

The next day, armed secessionists, some carrying nooses, surrounded the polling places. Inside, voters learned that the ballot wasn’t secret: They had to announce their votes aloud. In the town of Mount Crawford, a man named Harrison defied the mob, voted for Union and then headed home. “This company of men went after him and got him and brought him back,” a farmer named Joel Garber told the claims commission, “and said they were going to hang him.”

Harrison agreed to change his vote, and Garber, who’d planned to cast a ballot for Union, instead voted to secede: “I was afraid for my life.” The threats worked. Of more than 2,000 votes cast in the county, only 22 favored staying in the Union.

Secession meant war, as Elder Kline had predicted, and soon Confederate recruiters interrupted services at Mennonite and Brethren churches to demand that all men between the ages of 18 and 45 report for service in the army. Some men complied, secretly vowing that they’d never fire their weapon at another human being. Others refused to serve and were imprisoned. And many fled through the mountains, heading north or west, pioneering what would soon become a well-organized stream of refugees.

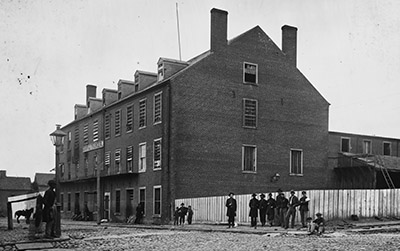

In March 1862, a group of about 70 men—most of them Mennonites or Brethren—were captured in the mountains and hauled to Richmond’s infamous Castle Thunder prison. Elder Kline and two other religious leaders were also arrested and sent to Castle Thunder. They were released about a month later, after the Confederate Congress passed a law permitting religious dissenters to avoid military service by paying a $500 fine. Some wealthy Mennonites and Brethren paid their fines and kept working their farms. But $500 was a huge sum in that era and many farmers couldn’t afford it. Those men also fled through the mountains, stopping to eat and rest at the farmhouses and churches that made up the underground railroad.

In March 1862, a group of about 70 men—most of them Mennonites or Brethren—were captured in the mountains and hauled to Richmond’s infamous Castle Thunder prison. Elder Kline and two other religious leaders were also arrested and sent to Castle Thunder. They were released about a month later, after the Confederate Congress passed a law permitting religious dissenters to avoid military service by paying a $500 fine. Some wealthy Mennonites and Brethren paid their fines and kept working their farms. But $500 was a huge sum in that era and many farmers couldn’t afford it. Those men also fled through the mountains, stopping to eat and rest at the farmhouses and churches that made up the underground railroad.

Elder Kline continued his ministry as a circuit-riding preacher, visiting Brethren churches in Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, Pennsylvania and Ohio. Some Rockingham County Confederates considered Kline’s trips to the North evidence that the pacifist preacher was a Yankee spy. On June 15, 1864, Kline was riding home after repairing a neighbor’s clock, when he passed two Confederate militiamen lying in ambush. One of them fired a bullet into Kline’s back. The preacher tumbled from his horse and lay gasping on the path. The soldier stepped forward, stood over the man who’d predicted that secession would kill some of his congregation, and delivered the coup de grâce: a single shot to Kline’s heart.

“This house looks pretty much like it did in the Civil War era,” Norman Wenger says, as he and Rodes stand in front of an old white house with a tin roof. During the Civil War, Jacob Miller owned this farmhouse. “Miller took over the leadership of the Brethren church when John Kline was killed,” he says. That was a terrifying job: Miller’s brother Daniel testified that Confederate soldiers threatened to kill Jacob shortly after Kline’s murder: “I heard them say he would be killed next and several more would be killed soon.”

Now, Wenger flips through Volume 2 of his Unionist books and reads from Miller’s deposition: “My name is Jacob Miller. I am 61 years old. I am a farmer and preacher in the Dunker church. . . . I aided and assisted a large number of refugees and deserters to escape from the Confederacy. I have kept them concealed or have fed them and sent them to other agents and guides. I have had them come to my house from distant counties in the night. My house was one of the Depots of the underground RR, as it was called.”

Wenger stops reading and looks up. “I was surprised to see people use the term ‘underground railroad’ in the depositions,” he says. “I thought that was a term people came up with a hundred years later. But they called it that themselves.” He adds that he and Rodes found no connection between the underground railroad in Rockingham County during the Civil War and the famous Underground Railroad that aided escaped slaves before the war.

Miller’s deposition is just one of dozens that mention Rockingham County’s underground railroad. Poring through thousands of pages, Wenger and Rodes pieced together a picture of how the operation worked. It was, they say, a “highly organized system,” run mainly by Mennonites and Brethren, and designed to guide men seeking to avoid Confederate service to safety behind Union lines. The underground devised its own code: A “refugee”—a draft dodger or deserter—would be taken to a “terminal” or “depot,” usually somebody’s farm, where groups of men would gather to wait for a “pilot” to guide them over obscure mountain paths to safety. The usual destination was New Creek, now known as Keyser, W.Va., the Union state on Rockingham’s border, where refugees could catch a B&O Railroad train to Northern towns.

Wenger and Rodes say they’ve identified more than 30 depots in Rockingham County. And they found references to 12 different pilots. “Mr. Keester and Mr. Ruderson were the principal pilots,” Andrew Lindsey, an active member of the underground, testified. “Mr. Keester told me he had taken about 2,000 men through [the mountains] during the last two years of the war.”

At first, most refugees were local Mennonites and Brethren, but by the end of the war, men came from farther south. “There are depositions that mention people coming from Georgia and North Carolina,” Wenger says. “I believe if you looked at all 22,000 claims in the National Archives, you’d find that this underground railroad was organized—loosely organized—in the entire South.”

Wenger’s speculation could well be true, says Dr. Victoria Bynum, professor emeritus of history at Texas State University and author of The Long Shadow of the Civil War, a study of pro-Union dissidents and guerrilla fighters in Confederate states.

“It is a reasonable supposition that a study of the Southern Claims Commission files would likely reveal other pockets of religious resistance to the Confederacy,” Bynum said in a recent e-mail interview. “There is evidence of secret networks of Unionists, and harboring of draft-age men, in other areas of the South. In North Carolina, the ‘Heroes of America,’ also known as the ‘red strings,’ are a perfect example. This [pro-Union] group had clear religious ties with Quakers, Wesleyan Methodists and perhaps the Moravians of central North Carolina.

“Southern Unionists,” she added, “are a vital topic of study among historians of the Civil War.”

Skeptics sometimes ask Wenger and Rodes the barbed question: How do you know that the people who filed these claims weren’t lying or exaggerating their pro-Union activities in order to convince the claims commission to give them money? It’s certainly possible that some people lied, the men respond, but highly unlikely that dozens of witnesses—including many who didn’t file claims—fabricated matching stories over nearly a decade about the underground railroad.

Skeptics sometimes ask Wenger and Rodes the barbed question: How do you know that the people who filed these claims weren’t lying or exaggerating their pro-Union activities in order to convince the claims commission to give them money? It’s certainly possible that some people lied, the men respond, but highly unlikely that dozens of witnesses—including many who didn’t file claims—fabricated matching stories over nearly a decade about the underground railroad.

“The stories fit,” says Rodes.

“I was a Depot Agent,” John Harshbarger testified. “We would harbor parties and feed them in our barn and in the woods until we could get a small company to our pilot.”

“I would prepare their rations and they would start for the mountains at night,” Margaret Rhodes told the commission. “We had a place under the floor under the house where we would conceal persons when necessary. It was entered by a trap door in my bedroom and covered by a carpet so no one would suspect anything.”

“When the refugees would come in for food, my brothers would watch for the coming of rebels while the refugees were eating,” Mary Gangwer testified. “We had a closet with a trap door to a large place behind a chimney where we concealed them.”

Despite the best efforts of the Unionist underground, not all the refugees reached the North. “Others were captured by the [Confederate] scouts, and their orders were to shoot them,” John F. Lewis, who later served as a United States senator from Virginia, told the commission. “Whenever a man was caught attempting to make his escape through the lines, they shot him.”

But the Confederate Army wasn’t the only danger to the Valley Unionists. The Union Army was also a threat. When General Sheridan rode through the Valley in the fall of 1864 with orders to destroy crops in the Confederacy’s breadbasket, his soldiers didn’t care about the political views of individual farmers. They stole the livestock and burned the barns of secessionists and Unionists alike.

Rodes’ great-great-great-grandparents, Abraham and Magdalenah Heatwole, operated one of the most active depots on the underground railroad, but that didn’t stop Sheridan’s soldiers from confiscating five of their horses, two saddles, 75 pounds of butter, 10 gallons of molasses, 40 gallons of apple butter, two barrels of flour and three bushels of sweet potatoes, according to Abe Heatwole’s deposition. They also stole, killed and butchered two sheep, two hogs and two cows outside the family barn. “I got a piece of one of the sheep and of one of the hogs,” Magdalenah testified, “and cooked it for our own family.” Her cooking must have smelled good: When she finished, the soldiers confiscated that meat, too.

Seven years later, in 1871, Abraham Heatwole filed a claim requesting $996.25 to pay for his losses. He and his wife told the commission about their role in the underground railroad, but they also admitted that Abe was so terrified by the mob outside the polling place in 1861 that he voted for secession. His claim was denied. “We regard the vote for a dissolution of the Union as the highest kind of disloyalty,” the commissioners wrote. “We therefore reject the claim.”

David Rodes stops the car again, this time in front of an old two-story brick house near the tiny town of Linville. Green ivy crawls up the house’s red brick columns. During the Civil War, the house belonged to Jacob Geil and his wife, Mary Wenger Geil.

“Mary Geil, she’s a sister of Jacob Wenger, so she would be my great-grand-aunt,” says Norman Wenger. He’s standing outside the old house, thumbing through another of his books until he finds Mary Geil’s deposition. “She says, ‘During the war we had at our house a great many refugees, which my husband kept and fed and harbored until the guides would come and take them to the mountains.’ ”

Mary’s husband stayed home on the day of the secession vote, which no doubt helped him with the claims commission. Geil requested $761 to pay for the horse, cattle, oats and hay seized by Sheridan’s soldiers. In 1877, the commission awarded him $480.

That’s interesting information but it’s not what Norman Wenger is looking for right now. He wants to find a phrase that Mary used in her deposition—a phrase that has become a running joke between Wenger and Rodes. He finds it a few lines down the page: “Our place was called by the secessionists as a ‘damned Union hole.’ ”

“A damned Union hole,” Rodes repeats, laughing.

Wenger says he never heard that story when he was growing up. “Most of these stories were never passed down,” he says, “because in the generation after the war, they didn’t want to talk about these things.”

In fact, some people still don’t want to talk about them. And Rodes eagerly tells a story about that. “I was interviewed by the newspaper, and I quoted Mary Geil saying the Confederates called this place a ‘damned Union hole,’ ” he says. “And a woman came into my gift shop and yelled across the room—15 people probably heard it—‘How dare you call my precious ancestor’s home a damn Union hole!’ And I said, ‘Ma’am, I didn’t call it that, but your great-great-grandmother did.” He bursts out laughing. “And if you’ve got a problem with that, you’ll have to talk to her.” n

Peter Carlson is a regular contributor to American History. His most recent book is Junius and Albert’s Adventures in the Confederacy: A Civil War Odyssey (PublicAffairs).