A bold rebel cavalry raid falls short at a mountain crossroads.

On August 1, 1864, war arrived with a vengeance in the western Maryland town of Cumberland. Days earlier, Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early had ordered nearby communities ransomed—and had burned Chambersburg, Pa., when the town refused to pay up. Now Cumberland, a rich but well-defended target about 100 miles southwest of Gettysburg, was next in his sights.

What began as the outpost Fort Cumberland in 1754—the last stronghold for British General Edward Braddock in his ill-fated 1755 expedition against French and Indian forces—had become the thriving hub of three major transport routes: the National Road, also known as the Baltimore Pike; the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal; and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. By 1860, it boasted a population of 7,302.

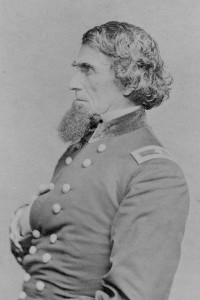

Since the start of the Civil War, there had been a strong Union presence in the town. In August 1861, the District of Grafton was established, with Cumberland placed under federal martial law and the authority of Brig. Gen. Benjamin F. Kelley. Union troops stationed in town varied in strength from 3,000 to as many as 8,000—more than the civilian populace.

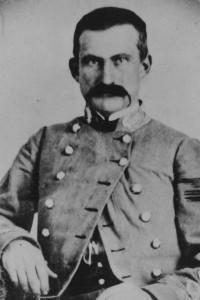

During the summer of 1864, Early retaliated on two occasions for Northern depredations in Virginia. In May and June, Union Maj. Gen. David Hunter had stormed through the Shenandoah Valley destroying food and supplies, levying fines on uncooperative towns, fending off guerrillas and burning the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington. At first Early headed for Washington. Early’s Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, reinforced with local units and renamed the Army of the Valley, staged a counterinvasion that reached the outskirts of Washington, D.C., on July 11. Facing Union forces, Early withdrew the next day. Then in late July, he regrouped for a second incursion, this time starting in Pennsylvania. On July 30, Brig. Gens. John McCausland Jr. and Bradley T. Johnson demanded $600,000 from Chambersburg residents. When that ransom wasn’t paid, approximately 500 of the town’s structures were burned. McCausland and his column then plundered McConnellsburg, 20 miles to the west, before heading southwest for Hancock, pursued by Brig. Gen. William W. Averell’s Union cavalry.

On the morning of August 1, McCausland reached Hancock, where his “request” for $30,000 nearly caused a mutiny from his own Marylanders—including his second in command, Johnson. Then Averell’s cavalry arrived and fighting broke out in the main street. And at that point McCausland received orders from Early to set out for the more lucrative target of Cumberland, 38 miles away, where he was to destroy railyards, bridges and coal pits. Early also instructed him to exact a ransom from the town’s citizens, threatening them with the same fate as

Chambersburg. Disengaging from Averell, McCausland pulled out of Hancock and headed west along the Baltimore Pike.

Anticipating the threat, Cumberland’s mayor, Dr. Charles H. Ohr, had all roads leading in and out of town barricaded and picketed by General Kelley’s troops. He also called for a home militia to be raised. Townsmen took up an assortment of arms ranging from rifles to shotguns, and shopkeepers hid their goods. Meanwhile the railroad companies sent their trains westward, beyond the Rebels’ reach. But many townsfolk gathered on the city heights to observe the coming confrontation.

The first shots were fired around noon near Flintstone, 12 miles northeast of town. Responding to a telegraph message received in New Creek, Lieutenant Tappan W. Kelley, General Kelley’s son, led a small detachment of the 11th West Virginia Infantry to reconnoiter and was soon skirmishing with McCausland’s scouts.

Meanwhile, 2½ miles east of Cumberland near John Folck’s mill, some of Kelley’s troops had positioned themselves along the Baltimore Pike and placed two sections of Battery L, 1st Illinois Light Artillery, at George Hinkle’s house on a hill. The balance of Kelley’s command—consisting of the 152nd and 156th Ohio Infantry (100-day men whose enlistment was due to expire within a few days) along with four companies of the 11th West Virginia; one company of the 6th West Virginia Infantry; and several hundred survivors of the Second Battle of Kernstown, fought a week earlier—entrenched on the city’s outskirts.

Aligned on Kelley’s right flank were the 200-man volunteer militia led by Brig. Gen. Charles Mynn Thruston, a West Point graduate and Cumberland resident. The 153rd Ohio Infantry, under Colonel Israel Stough, had been sent to Oldtown, Md., to secure the Potomac River crossing there in case the enemy tried to take Cumberland by a circuitous route, coming up from the south through Virginia, or to block his retreat if need be. Of the roughly 1,000 men on hand to defend Cumberland, the only battle-tested men were the 6th and 11th West Virginia, the three sections of Illinois and Maryland artillery and the stragglers from Kernstown—hardly a match for the 2,800 seasoned veterans descending on them.

At 3 p.m. a squadron of McCausland’s cavalry was crossing the covered bridge over Evitt’s Creek near Folck’s Mill when Federal artillery and skirmishers opened fire. Scrambling for cover around the Folck house, barn, grist and saw mills, and cooper shop, the troopers returned fire while McCausland brought the four guns of Captain John H. McClanahan’s battery into line and committed the remainder of his force.

During a three-hour exchange, McClanahan’s guns were well handled but proved to be largely ineffective against the Northern artillery emplaced on higher ground. Folck’s Mill sustained considerable damage, with one shot starting a fire in the barn that destroyed it.

The Confederates made several assaults, nearly succeeding in seizing ground on the Federal left flank before being driven back. At 6 p.m. McCausland and Johnson held a conference. Neither side had made any headway, but the Confederates, who were in unfamiliar territory facing what they (wrongly) believed to be numerically superior Federal forces, knew time was not on their side. As his troops disengaged and withdrew from Folck’s Mill, McCausland sent Major Harry Gilmor and his cavalry ahead to scout out an escape route.

Across the Baltimore Pike, Cumberland’s defenders established a field hospital at George Hinkle’s house. General Kelley reported that the engagement, which would be variously referred to as the Battle of Folck’s Mill, the Battle of Pleasant Mills or the Battle of Cumberland, had cost him one man killed and one wounded, though the number of wounded actually came to four. The Confederates left behind eight dead and 30 wounded, along with two caissons, carriages, a large amount of ammunition and some of their plunder from Chambersburg.

At 11 p.m. the Confederates began withdrawing from Cumberland’s outskirts, leaving their campfires burning as a ruse. Elements of the 153rd Ohio Infantry that were deployed on a narrow spit between the C&O Canal and the Potomac made it necessary for the Confederates to fight their way across the river, but they ultimately succeeded. After riding into Springfield, W.Va., they got a chance to rest on August 4 before setting out for New Creek to resume raids on the B&O Railroad.

On August 3, Cumberland’s Mayor Ohr and his council adopted the following resolution: “Whereas on Monday, the 1st of August, the peace and safety of our city was endangered by an invading enemy, and the military authorities called on the citizens for voluntary aid, therefore Be it resolved by the Mayor and Councilmen, That the thanks of the Mayor and Council of the City of Cumberland…are hereby tendered to those citizens and others who, at the call of the authorities, volunteered in the defense of the city by taking up arms and marching out to meet and repel the invading foe.”

On August 5, the council issued another resolution expressing their gratitude to General Kelley for saving the town and protecting them from “dreadful calamity, similar to that lately inflicted upon the people of Chambersburg.” And on that same day President Abraham Lincoln promoted Kelley to brevet major general. Cumberland held a grand review on August 11, honoring Kelley’s troops as well as citizen soldiers.

Never again would Cumberland face a significant threat from the Confederates, although raids continued on the B&O railroad. And in February 1865, Confederate partisan raider Jesse McNeill managed to reach the town undetected at night and capture General Kelley and Maj. Gen. George Crook. Both Union commanders were exchanged soon thereafter.

Debra Topinka, a reenactor and living historian of the Civil War for the past 15-plus years, writes from Bedford, Pa.