Editor’s note: This article differs from those that MHQ normally publishes. We expect our historians to answer the questions who, what, where, and when — as well as to provide readers with how and why. For reasons that will become apparent, however, Edward Drea’s treatment of the August 4, 1964, Gulf of Tonkin incident is by necessity more of an incomplete chronology than a history. Many of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s detractors have long claimed he escalated American participation in the Vietnam War through fraud by insisting that U.S. naval forces had been attacked on the night of August 4 when, in fact, they had not been fired upon. This event has been cited by a number of observers as the beginning of an age when Americans began to distrust the federal government. On the fortieth anniversary of the incident, it is time to update what we know about the event’s who, what, and when.

In the last several years, more information has been revealed through the declassification of some documents involving sensitive U.S. radio intercepts of North Vietnamese communications. We asked Ed Drea to write an article that would give our readers the flavor of the confusion during some of the most tense hours in U.S. history, when a shooting situation that occurred in one time zone sparked rapid-fire questions, analyses, and decisions in three other time zones. Drea is a contract historian at the Pentagon, hence the need to publish what MHQ has never before printed, the stock Department of Defense disclaimer: ‘The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

U.S. Naval Historical Center |

| At the time of the August 2 attack, USS Maddox was on an intelligence-gathering mission thirty miles off North Vietnam’s coast. |

Darkness was falling over the Gulf of Tonkin on August 4, 1964, when at 8:40 p.m. Saigon time (8:40 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time [EDT]) the destroyer USS Maddox, on patrol, issued a high-priority message, or critic report: Received information indicating attack by PGM/P-4 [North Vietnamese navy PT-boats, or Swatows]. Proceeding Southeast at best speed.

The source of the information was a U.S. field-site warning dispatched exactly one hour earlier, at 7:40 Saigon time, by flash precedence to Maddox, its fellow destroyer Turner Joy, and other addressees. Partially declassified in March 2003, the message reads: Haiphong informed Vessel T142 (Swatow Class) to make ready for military operations the night of 04 August. The sister ship, T-146 has also received similar orders. Message exchanges indicate that all efforts are being made to include MTB (Motor Torpedo Boat) T333 in this operation, as soon as additional oil can be obtained for that vessel.

Just three minutes later the same unit transmitted another warning to Maddox: At 0910Z [Zulu, or Greenwich Mean, time], Haiphong informed Vessel T142 of DeSoto destroyers location: Time 1345 (Golf [Hanoi time]) 106-19-30E/19-36-23N. Haiphong’s tracking was accurate.

Aboard Maddox, Captain John J. Herrick, commander of the two-destroyer task group CTG 72.1, and the destroyer’s skipper, Commander Herbert L. Ogier, had cause for alarm. Swatows were Chinese-manufactured motor gunboats capable of making twenty-eight knots. The eighty-three-foot-long vessels carried a crew of thirty men armed with 37mm and 14.5mm guns, as well as surface search radar and depth charges. P-4s were Soviet-built motor torpedo boats that could exceed fifty knots. Though smaller and with an eleven-man crew, the P-4 carried two torpedoes with a range of forty-five hundred yards. The warning was all the more ominous because one of the North Vietnamese navy vessels identified in the message — T-333, assigned to Division 3 of PT Squadron 135 — had attacked Maddox thirty miles off the North Vietnamese coast two days earlier.

Just after 4 p.m. on August 2, the three P-4 PT-boats had closed on Maddox at speeds approaching fifty knots. The first boat launched a torpedo, then broke off as the two other vessels bore in on their target. One PT-boat fired two torpedoes at Maddox, but was hit by the destroyer’s return fire. Meanwhile the first boat reengaged the destroyer, maneuvering to within two thousand yards while launching a torpedo and firing its 14.5mm guns at the U.S. ship. Maddox‘s guns heavily damaged the boat and killed its commanding officer. Around 4:30 p.m. the North Vietnamese turned toward shore. Shortly afterward, U.S. Navy planes from the aircraft carrier Ticonderoga attacked the withdrawing boats, leaving one dead in the water. During the fighting, T-333 suffered damage to an auxiliary engine that left it with a low lubrication oil pressure reading but otherwise fit for action. Only a single round of North Vietnamese fire hit the destroyer. Anti-aircraft fire from the P-4s, however, hit one U.S. Navy plane, forcing it to divert to Da Nang. There could be no doubt about an attack launched in broad daylight that had inflicted damage on both sides.

What happened in the Gulf of Tonkin on August 4, however, remains shrouded in controversy. Did North Vietnamese patrol boats attack Maddox and Turner Joy? Did a naval battle occur that night, or was it rather the case, as President Lyndon B. Johnson told Under Secretary of State George Ball a few days later, that those dumb, stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish? The issue is more than one of historical curiosity, because on the basis of the second attack Johnson ordered retaliatory airstrikes against North Vietnamese targets and secured from Congress the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which he thereafter used to validate his decisions to escalate the American role in the war in Southeast Asia.

North Vietnamese authorities, including no less a figure than General Vo Nguyen Giap, vice premier for defense in 1964, have consistently denied an attack took place on August 4; an official North Vietnamese military history of the conflict labels the engagement a U.S. fabrication. Perhaps of greater importance, at the time of the incident several U.S. senators disputed the administration’s account, and hearings before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in February 1968 aired serious doubts that a second attack had actually occurred. In 1972 Dr. Louis Tordella, then deputy director of the National Security Agency, concluded that certain of the intercepted North Vietnamese messages referred to events of August 2, not August 4, a view endorsed in 1984 by Ray S. Cline, the CIA’s deputy director for intelligence at the time of the action. Even former secretary of defense Robert S. McNamara, the chief architect of U.S. military escalation in Vietnam during 1965, appears to have changed his mind. As late as 1995 he believed that the attack seemed probable but not certain, but in 1999 McNamara wrote that there was no second attack. First-person accounts of what happened differ as well. Carrier pilots defending Maddox the night of August 4 strafed the waters where the enemy boats were reported, but most, including Medal of Honor recipient Commander James Stockdale, did not see any hostile craft. According to the debriefing report sent to Washington, another pilot, the commanding officer of the attack squadron, flying between seven hundred and fifteen hundred feet over the destroyers, spotted gun flashes and light anti-aircraft bursts at his altitude as well as a snakey high-speed wake 1 1/2 miles ahead of Maddox. The command pilot himself only recalled a short debriefing in which he had answered no when asked if he had observed enemy PT-boats. On the other hand, several crew members aboard the destroyers saw torpedo wakes, ships’ running lights, searchlights, and gunfire flashes.

Amid these allegations and counterclaims, exactly what happened on the night of August 4, 1964, in the Gulf of Tonkin will likely remain unresolved until the United States and Vietnam completely open their archival material on the incident. There is little chance of that happening in the immediate future, but based on the incomplete but recently expanded record, a chronological review of participants’ actions — from the deck of Maddox to the Cabinet Room of the White House — will at least provide a better picture of what U.S. civilian and military leaders thought was happening.

Shortly after assuming the presidency in November 1963, Johnson instructed his senior policymakers to devise covert missions targeting North Vietnam in order to discourage the regime’s support of Viet Cong operations against the U.S.–backed Saigon government. Their answer was OPLAN (Operations Plan) 34-A, a series of commando raids beginning in January 1964 against selected targets in North Vietnam, including raids on coastal areas by high-speed patrol boats. Following an early March 1964 trip to South Vietnam, Secretary of Defense McNamara recommended stepped-up retaliatory measures against North Vietnam, which were adopted on March 17 as National Secu-rity Action Memorandum No. 288.

As U.S.–directed covert operations conducted by South Vietnamese boat crews and raiders intensified in the late spring and early summer of 1964, North Vietnam’s Politburo of the Party Central Committee instructed the country’s armed forces in June to destroy any enemy violating their territory. On July 6, the North Vietnamese navy went on wartime status, and to counter the OPLAN 34-A raids along the coast, naval headquarters established a forward headquarters under Nguyen Ba Phat, deputy commander of the navy, near Quang Khe, a PT base located between Vinh and Dong Hoi, the area hardest hit by South Vietnamese commandos. Naval units were placed on high alert, sailors and cadre were recalled from leave, and torpedo boats conducted familiarization and operational training. The general staff and navy headquarters ordered the 135th Torpedo Boat Squadron, stationed at Ben Thuy and Quang Khe, to attack any enemy vessel invading territorial waters.

Concerned that the North Vietnamese buildup would make future commando raids ashore prohibitively expensive, on July 24 McNamara asked his military advisers if offshore bombardment might serve the same purpose. In the early morning hours of July 31, four OPLAN 34-A vessels shelled Hon Me and Hon Nieu, islands north of Vinh. The two boats bombarding Hon Me were in turn attacked by North Vietnamese gunboats and pursued unsuccessfully by Swatow T-142.

Simultaneously, the U.S. Navy was running electronic intelligence collection sweeps, code-named Desoto, along North Vietnam’s coast. On July 15, Admiral U.S. Grant Sharp, commander in chief, Pacific (CINCPAC), requested a Desoto patrol. Washington approved it, and two days later Maddox received its mission orders. The destroyer entered the Gulf of Tonkin on July 31 and proceeded to its designated patrol track parallel to the North Vietnamese coastline. As McNamara has pointed out, the Desoto patrols sailed only in international waters conducting electronic reconnaissance and were substantially different from the OPLAN 34-A combat operations that routinely violated North Vietnamese territorial waters. While the missions of the two were unlike in nature, both involved enemy warships transiting the Gulf of Tonkin and approaching the North Vietnamese coast. Hanoi could understandably regard a U.S. destroyer’s presence, in some cases only eight nautical miles offshore, as a backup should the smaller OPLAN 34-A vessels find themselves in trouble. Thus, early on August 2, North Vietnamese naval headquarters reinforced Hon Me with three P-4s and ordered preparations for battle. That afternoon the P-4s attacked Maddox.

U.S. Naval Historical Center |

| Maddox‘s executive officer, Lt. Cmdr. Dempster M. Jackson, kneels next to the only damage the destroyer sustained in that attack: a machine gun bullet hole. |

U.S. Naval Historical Center |

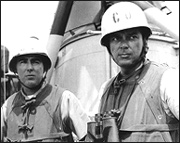

|

Captain John J. Herrick (left), standing next to Maddox captain Commander Herbert Ogier, was in charge of a two-destroyer task group during the alleged August 4 attack.

|

North Vietnamese authorities have since claimed that their local naval commanders acted on their own initiative during the Gulf of Tonkin incidents. But the presence of the deputy commander of the navy on scene, as well as intercepted messages that indicate a higher headquarters in Haiphong was routinely passing orders and maintaining a communications link with the forward PT-boat bases, suggests that control was more highly centralized than believed then or now. On August 2, 1964, for example, Lyndon Johnson also concluded that an overeager North Vietnamese boat commander or a local shore station, rather than a senior commander, might have miscalculated in ordering the attack and so decided against any retaliation. As LBJ reported to the American people the following day, however, he did double the strength of the Desoto patrol, provide it with air cover, and order the commanders of the two destroyers and combat aircraft not only to defend against patrol boat attacks but also to counter attack and destroy any force attempting to repeat the attacks.

On the night of August 3, two OPLAN 34-A PT-boats fired more than seven hundred rounds of 57mm and 40mm ammunition at a North Vietnamese radar site near Vinh Son while another boat shelled a security post at the mouth of the Ron River. North Vietnamese ashore returned fire on the single boat, and a North Vietnamese navy patrol boat pursued it in vain. The same night, the commander of the Seventh Fleet, Vice Adm. Roy L. Johnson, recommended to Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, commander in chief, Pacific Fleet, that the Desoto patrols be ended after the August 4 mission. Moorer disagreed, contending that terminating the patrol two days after the attack would indicate a lack of American resolve. The president, after all, had publicly announced that the ongoing patrol would continue, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) had already cabled Admiral Sharp to continue the patrol, reinforced by Turner Joy, and avoid approaches to the North Vietnamese coast while OPLAN 34-A operations were underway.

On the morning of August 4, while preparing for the day’s mission, Herrick informed Admiral Johnson that various intelligence sources suggested the North Vietnamese directly linked the OPLAN raids and the Desoto patrols and would consequently treat the United States as an enemy. Nevertheless, higher headquarters and the White House seemed to accept the risk of another attack, and the patrol continued. Given these circumstances, Herrick took the field unit’s warning of impending North Vietnamese action very seriously.

The field site’s 7:40 p.m. Saigon time warning to Maddox of indications of an imminent attack reached the Defense Intelligence Agency Indications Center in the Pentagon by phone at 8:13 a.m. on August 4. While the watch officer was on the phone, the message itself arrived from a field unit stating there were imminent plans of DRV [Democratic Republic of Vietnam] naval action possibly against DeSoto mission. Around 9 a.m., the Indications Center team chief briefed General Earle G. Wheeler, chairman of the JCS, and Secretary McNamara. Wheeler was to attend a meeting in New York City with the New York Times editorial board that morning, and he and McNamara agreed that he should keep the appointment because a sudden cancellation might result in speculation that a military crisis was brewing.

Twelve minutes later, McNamara phoned President Johnson to tell him that Maddox was again on alert, reporting the presence of hostile ships and based on U.S. intercepts of North Vietnamese communications…suspected that an attack seemed imminent. Meanwhile, at 8:36 p.m. Saigon time USS Ticonderoga had reported that Maddox, then sixty-five miles from the nearest land, had radar fixes on two unidentified surface vessels (skunks) and three unidentified aircraft (bogies). (This report took almost two hours to reach the National Military Command Center, arriving at 10:30 a.m. EDT.) In the dark, moonless night in the Gulf of Tonkin, low clouds and thunderstorms further restricted visibility, leaving Maddox dependent on its radar and sonar arrays for data throughout most of the action that followed.

After receiving the destroyer’s message about radar contacts, Ticonderoga had launched fighter aircraft to protect Maddox from possible attack. Thirty-two minutes later, at 10:08 Saigon time, a message relayed from Maddox reported that the bogies had dropped off the radar screen and the surface contacts were maintaining a twenty-seven-mile distance without attempting to close on the ship. At 10:34 Rear Adm. Robert B. Moore, commander of Carrier Task Force 77, aboard Ticonderoga, signaled: The two original Skunks opened to 40 miles. Three new Skunks contacted at 13 miles. Closed to 11 miles. Evaluated as hostile. CAP (Combat Air Patrol)/STRIKE/PHOTO [attack aircraft/reconnaissance aircraft] overhead under control of Maddox. Six minutes later Maddox flashed, Commenced fire on closing PT boats.

While these events were transpiring in the Gulf, McNamara, Deputy Secretary of Defense Cyrus R. Vance, Lt. Gen. David A. Burchinal (director of the Joint Staff, JCS), and other military officers had been meeting at the Pentagon since 9:25 a.m. to discuss possible options should the North Vietnamese again attack a U.S. Navy ship in international waters. At 9:43 the president returned from his breakfast meeting with congressional leaders and phoned the secretary of defense for more details of events in the Gulf of Tonkin. McNamara informed him that Admiral Sharp had recommended that the task force commander move closer to shore and be authorized to pursue and destroy any attackers, including airstrikes against naval bases. McNamara thought that a bad idea because it forfeited Washington’s ability to control a measured response to North Vietnamese aggression.

President Johnson worried that allowing North Vietnam to shoot first made the United States appear reactive, and he thought we not only ought to shoot at them, but almost simultaneously pull one of these things that you’ve been doing — on one of their bridges, or something. McNamara quickly agreed, but still rejected Sharp’s wholesale approach. Johnson concurred, but added that he wished there were targets already picked out so planes could just hit three of them damn quick and go right after them. We will have that, McNamara assured the president. In fact he had just told Special Presidential Assistant McGeorge Bundy that they should have a retaliation move against North Vietnam ready for the president in the event this attack takes place within the next six to nine hours. Johnson and McNamara decided to discuss those options at a scheduled White House lunch that afternoon.

McNamara then huddled with JCS representatives and Vance at the Pentagon to examine incoming reports of the rapidly developing situation and discuss possible alternative methods of retaliation, such as air attacks against naval bases, airfields, bridges, and POL (petroleum, oil, and lubricant) installations, or the mining of one or more important North Vietnamese ports.

During the meeting, McNamara was repeatedly called away to the phone. At 9:55 he told Secretary of State Dean Rusk that he was inclined to do much more than go after the boats as Rusk had suggested, and that the president agreed with the tougher position. At 10:19 McNamara phoned Admiral Sharp in Honolulu (where it was 4:19 a.m.) about a possible attack on Maddox and was emphatic that the navy could use whatever force it needed to destroy the attacking craft. When Sharp said four aircraft were launched until an attack happens, McNamara interrupted, Oh, yes, surely, I understand that, but after the attack happens, you wouldn’t feel limited to 8 or 10 or anything like that.

At 10:33 McNamara signed JCS message 7700 to Sharp, which changed the rules of engagement by authorizing U.S. aircraft, previously restricted to operations during daylight hours seaward of the destroyers, to pursue any attackers to within three nautical miles of the North Vietnamese coastline. The same message confirmed earlier verbal orders to the carrier Constellation to join Ticonderoga in the Gulf.

Twenty minutes later, McNamara again phoned the president to update him based on Ticonderoga‘s 041236Z (8:36 p.m. Saigon time) message about Maddox detecting unidentified planes and ships on its radar and the carrier launching fighter aircraft to protect the destroyer from possible attack. He reassured Johnson that there were ample forces available in the Gulf to retaliate, and explained that for good measure only two hours earlier he had ordered Constellation to move down toward South Vietnam. McNamara also promised to give the president a list of targets when he arrived at the White House for their noon meeting. By this time the Pentagon conferees had narrowed potential targets to four options: airstrikes against PT-boats and their bases, against POL targets, against bridges, and against prestige targets, such as steel mills. General Burchinal also informed McNamara that retaliatory attacks could be made at first light in North Vietnam, or around 7 p.m. Washington time.

Meanwhile Burchinal had also been on the phone with CINCPAC headquarters, alerting Sharp to the changed rules of engagement and evaluating possible reprisal targets. Toward the end of their 10:59 conversation, Sharp said he just got a report saying that DESOTO Patrol is under continuous torpedo attack. Burchinal had not yet received that message, but promptly told McNamara, who notified the president two minutes later. The defense secretary asked the president’s permission to get Rusk and Bundy to the Pentagon to go over these retaliatory actions. With little other information available on the fighting in the Gulf, Johnson agreed. McNamara then phoned Rusk, informed him of developments, and asked him to come to the Pentagon.

McGeorge Bundy joined Rusk at the 11:40 meeting in the Secretary’s Dining Room in the Pentagon. McNamara briefed them on target options, discussed retaliatory measures, and with Bundy thrashed out the pros and cons of limited airstrikes and mining the North Vietnamese coast. McNamara also told General Curtis LeMay, sitting in for the absent Wheeler, that the JCS should prepare recommendations for immediate action as well as proposals for the next 2 1/2 days. Burchinal had again contacted Sharp at 11:18 and told him in circumlocutory language over an open phone line that contemplated actions involved something more severe than going right in and picking up secondaries. The two officers agreed strikes at first light were preferable.

>

|

At 12:04 the meeting broke up. McNamara continued discussions with Vance, Bundy, and Rusk in his office while the JCS resumed deliberations in the Secretary’s Dining Room. The chiefs had narrowed alternatives to three: sharp air attacks against a variety of targets, continuing pressure by mining the coast, or a combination of both. At 12:20 McNamara, Rusk, and Bundy departed for the White House while Vance went to ask the chiefs whether it would make any difference if retaliatory strikes were conducted at first light. After learning from them that it would make no difference, Vance left for the White House at 12:25. The JCS continued meeting until 1:49 and directed Burchinal to call McNamara at the White House to recommend their option first.

At 12:22 Sharp had updated Burchinal by phone that the North Vietnamese had fired at least nine torpedoes and lost two boats in the attack and that Constellation had launched several aircraft, which were at the scene of the action. During their conversation, Sharp was handed another message confirming two enemy craft sunk, ten torpedoes fired, U.S. aircraft overhead, and no U.S. casualties. Based on the number of torpedoes, Sharp suspected that more than three boats were involved in the attack.

Eighteen minutes later, McNamara’s group arrived at the White House from the Pentagon and interrupted a National Security Council (NSC) meeting about the situation in Cyprus, where fighting had broken out between Greeks and Turks. McNamara briefed participants on what was known about developments in the Gulf of Tonkin, and Rusk informed them that he, McNamara, and the JCS were preparing alternatives for response, but these were not yet ready. Following the NSC meeting, at 1:04 Rusk, McNamara, Bundy, Vance, and Central Intelligence Agency Director John McCone joined President Johnson for lunch.

After another twenty minutes, McNamara phoned General Burchinal for an update on the unfolding situation. The general reported the chiefs’ unanimous recommendation that three PT bases south of the 20th parallel and POL facilities at Vinh and Phuc Loi be attacked. He then added that another intercept claimed an enemy boat wounded and an enemy plane falling from the sky. The decryption, recently declassified, read: At 041154Z Swatow Class PGM T-142 reported to My Duc (19-52-45N 105-57E) that an enemy aircraft was observed falling into the sea. Enemy vessel perhaps wounded.

Alarmed about the reported shootdown, McNamara told Burchinal to contact Sharp for an up-to-the-minute account of the engagement and call him back. He then informed the president of the latest intelligence.

During the general and admiral’s conversation, Sharp could add nothing for Burchinal except some indication that a U.S. aircraft might have been hit by enemy fire. He was aware of the intercept and promised to call back with further details. About half an hour later, Sharp phoned Burchinal only to say that he was unable to contact the task force by voice. The steady stream of flash precedence messages up and down the chain of command by this time had overloaded the military communications circuit, forcing Sharp to prohibit CINCPAC from sending further messages at flash precedence. Even so, communications throughout the day were consistently slower than McNamara and Sharp expected, with repeated delays caused by clarifying events, transmitting orders, and making decisions.

To further complicate the situation, Sharp also told Burchinal that the latest report from Herrick, commander of the destroyer task force, questioned the reported contacts and number of torpedoes fired because Maddox had no visual sightings of North Vietnamese patrol boats. The message, sent from Maddox at 1:27 p.m. EDT read: Review of action makes many reported contacts and torpedoes fired appear doubtful. Freak weather effects on radar and overeager sonarmen may have accounted for many reports. No actual visual sightings by Maddox. Suggest complete evaluation before any further action taken. Burchinal said he would pass on Herrick’s doubts to McNamara.

At 2:08 p.m. EDT, Sharp again called Burchinal to relay Rear Adm. Moore’s latest situation report. Moore, then aboard Ticonderoga, claimed in a message sent thirty-six minutes earlier that three PT-boats had been sunk. Sharp acknowledged that excited sonarmen had probably overestimated the number of torpedoes fired at Maddox. Asked if he was pretty sure there was a torpedo attack, Sharp replied, No doubt about that, I think.

One more significant piece of intelligence reached McNamara at the White House early that afternoon. An intercepted message, again from PGM T-142, reported shooting at two enemy planes and damaging at least one. We sacrificed two comrades but all are brave and recognize our obligation, stated the message. According to Lyndon Johnson’s recollections, experts said this meant either two men or two boats in the attack group were lost. Certain from this evidence that the North Vietnamese were again attacking U.S. ships on the high seas, the president agreed on a sharp retaliatory strike against four PT-boat bases and the Vinh oil complex. He ruled out an attack on Haiphong and mining operations.

Asked by Johnson how long it would take to execute the strike, McNamara estimated from the information he had received that an attack could be launched in about four hours, at 7 p.m. EDT, which was first light at 7 a.m. August 5, Saigon time. The president suggested McNamara call the JCS to confirm the time, but the defense secretary indicated his preference to work out the details after his return to the Pentagon. At the close of the meeting, Johnson ordered the full NSC to convene at 6:15 to review his decision and a meeting of congressional leaders at 6:45 so he might inform them of his decision.

Upon his return to the Pentagon at 3, McNamara and Vance immediately joined the JCS, who were meeting in the Tank. McNamara told them that the President wants the strikes to take place at 7:00 PM Washington time, if possible, and identified the likely targets. They agreed with the objectives and the schedule. While the JCS drafted the execute message for transmission to CINCPAC, doubts about what had actually happened in the Gulf of Tonkin continued to emerge.

With Herrick’s 1:27 message in hand and following Johnson’s instructions, McNamara phoned Sharp at 4:08 for clarification. Was there a possibility, he asked, that there had been no attack? Sharp, citing an updated summary of Herrick’s later 2:48 EDT situation report, acknowledged there was a slight possibility because of freak radar echoes, inexperienced sonarmen, and no visual sightings of torpedo wakes.

Herrick’s 2:48 message read:

Certain that original ambush was bonafide. Details of action following present a confusing picture. Have interviewed witnesses who made positive visual sightings of cockpit lights or similar passing near Maddox. Several reported torpedoes were probably boats themselves which were observed to make several close passes on Maddox. Own ship screw noises on rudders may have accounted for some. At present cannot even estimate number of boats involved. Turner Joy reports two torpedoes passed near her.

Sharp was at that moment trying to learn more from CINCPAC Fleet and expected an answer within an hour. That said, McNamara complicated Washington’s timing because, he said, We don’t want to release news of what happened without saying what we are going to do; we don’t want to say what we are going to do before we do it. The reports had to be reconciled because We obviously don’t want to do it until we are damn sure what happened. Sharp then suggested holding the execute order until he confirmed the incident. With the strikes scheduled for 7, that gave him two hours, leaving one hour for notification to the carriers. Sharp still thought a 7 o’clock launch was possible, if tight, and told Burchinal at 4:40 p.m. EDT that a recent message indicated the North Vietnamese ambush was bonafide, although exact details were still confusing.

With this information in hand, McNamara, Vance, and the JCS met at 4:47 to determine whether an attack had actually taken place. They decided one had, based on five factors:

1. Turner Joy was illuminated when fired on by automatic weapons.

2. One of the destroyers observed cockpit lights.

3. PGM T-142 fired at two U.S. aircraft.

4. The North Vietnamese navy had announced that two of its boats were sacrificed.

5. Sharp’s determination that an attack had occurred.

Despite Lyndon Johnson’s effort to keep the lid on the latest incident, at 5:09 McNamara phoned the president to inform him that The Associated Press and United Press International were carrying reports of the latest PT-boat attack on their news tickers. He suggested, and Johnson approved, a noncommittal statement confirming the attacks but providing no further details.

|

At 5:23 Sharp again phoned Burchinal, asking if he had seen the intercept that described the sacrifice of two ships. The general had, but could not tell if it referred to the earlier action of August 2 or the August 4 incident. Sharp was certain it related to the recently concluded fighting and claimed the intercept pins it down better than anything so far. Burchinal assured Sharp that McNamara too was satisfied with the evidence. Six minutes later the JCS transmitted the execute order to CINCPAC directing that by 7 p.m. EDT the carriers launch a one-time maximum effort attack against the five PT bases (the northernmost was later canceled because of weather) and the Vinh oil installation.

During their 5:23 phone conversation, Sharp had informed Burchinal that the airstrikes could not be launched until 8 p.m. Washington time because the carriers operated in a different time zone, one hour behind Saigon. The admiral had also told the carriers to use the extra hour to complete preparations for their attacks.

Throughout the day, Admiral Sharp and General Burchinal had repeatedly assured McNamara that it would be a simple matter to launch an airstrike at first light in the Gulf of Tonkin. When this turned out not to be the case, General Wheeler, who had just returned to Washington, instructed Burchinal to tell McNamara that the carriers could not meet the 7 p.m. launch time as promised because they were operating in the different time zone. Since the president intended to address the nation on the airstrikes at 7, McNamara had a serious problem.

At 6:07 EDT Sharp called Burchinal to confirm that the execute message was agreeable to McNamara, which Burchinal assured him it was. The admiral also acknowledged aircraft would be off target by 9 p.m. EDT. When making his calculations, Sharp apparently discounted the toll Ticonderoga‘s extensive night operations in support of the two destroyers had taken on flight and deck crews, which now had to ready the carrier for a maximum effort.

Eight minutes later, McNamara, along with the president and his other senior civilian advisers and General Wheeler, attended the 538th meeting of the NSC. McNamara briefed the members on the North Vietnamese attacks and told them the administration had decided on airstrikes against five targets. He outlined a four-point program involving airstrikes, sending reinforcements to the region to demonstrate resolve, a presidential announcement of these actions, and a joint congressional resolution in support of these and, if necessary, further actions. United States Information Agency Director Carl Rowan asked exactly what had happened and whether it was certain that an attack had occurred. McNamara answered that only highly classified information nails down the incident, and more would be known from incoming reports and in the morning. A draft joint resolution on Southeast Asia was revised, and the president would make it public as soon as U.S. planes were over their targets, which McNamara assumed would be 9 p.m.

At 6:45 the president met with congressional leaders, and McNamara again summarized what was planned. After briefings by Rusk and McCone, Johnson and his advisers answered a series of questions. The president then summarized his case for congressional concurrence with his decisions and reminded his audience that We can tuck our tails and run, but if we do these countries will feel all they have to do to scare us is to shoot at the American flag. The question is how do we retaliate. With expressions of support from all present, the president prepared for his 9 p.m. address to the nation. As the minutes ticked by without further word from CINCPAC that the planes were airborne, McNamara grew increasingly impatient. At 8:39 he phoned Sharp, told him it was forty minutes past the ordered time for takeoff, and instructed him to radio the carriers and find out what was happening. After all, the president expected to make an address to the American people, and I am holding him back from making it, but we’re forty minutes past the time I told him we would launch. Asked how long it would take the planes to reach their targets after launch, Sharp answered a little over an hour. Minutes passed, and the 9 o’clock airtime came and went.

At 9:09 McNamara again phoned Sharp, who told him the carriers would launch their planes in fifty minutes. Oh, my God, gasped McNamara. Sharp then said the planes would be over target at 11 p.m. EDT. The conversation became more and more confused as McNamara tried to pin Sharp down. Was it two hours to the closest target? Sharp assumed that this meant the last TOT (time over target). With a 10 p.m. EDT launch, what was the first TOT? Sharp had no idea. Could the president say at 10, the time of launch, that the air action was in progress against gunboats and their supporting facilities? That, said Sharp, was not a good idea because it would alert the North Vietnamese.

McNamara then phoned President Johnson with news of the delay and suggested that he postpone his address until 10 and leave out the passage about air action now in progress. What, Johnson wanted to know, had delayed the attack? Briefing crews on the mission and loading designated ordnance, McNamara replied. The last aircraft would be off target at about midnight, Washington time. Johnson worried that a premature announcement would leave him vulnerable to charges that he tipped off the enemy to the impending actions, and he would sure as hell hate to have some mother say, ‘You announced it and my boy got killed.’ McNamara assured him there was little danger that would happen, and asked how late Johnson would be willing to hold off his statement. The president replied the 11 o’clock news, but wondered if he even had to make a statement. McNamara was emphatic that something needed to be said. The president walked a tightrope over the timing of his address. He had to avoid alerting the North Vietnamese to the air attacks but at the same time precede any announcement by Hanoi of the raids.

With still no word of any launch, McNamara contacted Sharp at 9:22 urging him to get the aircraft off their carriers, but to no avail. Again at 10:06 McNamara called, and Sharp told him that although he had received no word, he was sure that one outfit went up at 10. But, he said, Constellation was not going to launch its propeller aircraft until 1 a.m. EDT August 5 and its jet fighters at 2:30 a.m. The launches were delayed because the carrier could not get into position. You got that, sir? Yes. My God, snapped McNamara, who told Sharp to get in touch with Ticonderoga and make damn sure she got off. Forty minutes later McNamara tried again, with the same result. Sharp still had no word on any launch. Could not Sharp ask in the clear if the 10 o’clock thing had happened? The president wanted to go on the air at 11:15, and he shouldn’t go on unless he has a confirmation of a launch. Sharp said he was needling them like mad but the circuit is a little jammed up or something.

Only ten minutes before the president was to go on national television, Sharp phoned McNamara to report that Ticonderoga had gotten its planes off fifty minutes earlier, at 10:30 EDT. They would be over target in one hour and fifty minutes. McNamara was confused. How could it take so long — 2 1/2 hours — to reach their targets? Sharp explained that the planes launched in two waves, slower ones first, and then formed up to make a coordinated attack. Still, the time interval between takeoff and attack surprised both Sharp and McNamara, who had assumed the time from first launch to actual strike would be about forty minutes to one hour. When McNamara phoned the White House at 11:25, the president was unable to take the call, so McNamara told McGeorge Bundy that the planes were airborne. Bundy replied that Johnson would speak in about ten minutes.

Sharp, however, had misunderstood the launch information. Only four propeller-driven A-1 Skyraiders had taken off, and they orbited the carrier until 11:15 before departing for their targets. Ticonderoga launched its jet aircraft between 12:16 and 12:23 August 5 — that is, after the president addressed the nation and while McNamara was telling reporters at the Pentagon that naval aircraft from both carriers have already conducted airstrikes against the North Vietnamese bases from which these PT-boats have operated. Constellation, as Sharp had told McNamara, launched its first aircraft at 1 a.m. on August 5, followed ninety minutes later by a second wave.

Ticonderoga‘s aircraft struck southern ports first, and three hours later Constellation‘s pilots attacked northern targets. During the later raids, North Vietnamese anti-aircraft gunners shot down two U.S. aircraft, an A-1 Skyraider over the Loc Chau PT-boat base and an A-4 Skyhawk at Hon Gay, northeast of Haiphong. The Skyraider airman was killed, while the A-4 pilot, Lt. j.g. Everett Alvarez Jr., parachuted from his damaged aircraft and spent the next 8 1/2 years in captivity in Hanoi.

Johnson had second thoughts about the two lost aircraft, but Bundy assured him there was no evidence that his public announcement had adversely affected the operations in any way. According to Bundy, North Vietnamese radar operators had picked up the carrier planes before Johnson spoke on national radio and television. Post-strike assessments, Bundy told Johnson, revealed there was no significant alert at the ports struck by the first attack from Ticonderoga. The loss of two planes occurred during Constellation‘s attacks, which were hours later, long after the North Vietnamese went to full alert following the first attack.

On August 4, 1964, amid confusion, uncertainty, misinformation, and painfully slow communications, senior administration officials had to make a critical decision. One might speculate on why they made the one they did. After the August 2 attack in the Gulf of Tonkin, from the decks of Maddox to the halls of the Pentagon, everyone was on edge about the possibility of another North Vietnamese attack. Official Washington was predisposed to strike back given any future provocation. With those preconceptions, it became less important to question the accuracy of events on the night of August 4 than to ready a retaliatory strike. In brief, most attention and energy went into responding to, not assessing, what had happened.

Time constraints placed further pressure on decision makers. Any retaliation, they believed, had to be carried out right away to demonstrate U.S. resolve to North Vietnam and had to be clearly linked to the provocation to justify the response. Waiting several days to sort out the last detail of the August 4 action would blur any linkage and raise questions about the propriety of attacking well after the fact instead of at the time of the provocation. Once U.S. wire services began reporting the new attacks of August 4, there seemed even more reason for Johnson to act quickly.

Neither Washington nor Hanoi had been willing to blink. The administration stepped up OPLAN 34-A operations, Hanoi reacted by reinforcing its coastal naval units in the southern panhandle, the United States ordered a Desoto patrol, OPLAN 34-A raids continued, and North Vietnamese PT-boats attacked Maddox on August 2. Several intercepted North Vietnamese messages were ambiguous. The one McNamara cited as proof positive that an attack occurred may be a recap of the August 2 action intercepted during retransmission to another recipient. But the intercept that got Herrick’s attention ordered North Vietnamese PT-boats and Swatows to make ready for military operations on the night of August 4. One may question whether military operations meant attack, but the August 4 reference left prudent commanders like Herrick and Ogier little choice but to expect trouble in the Gulf that night.

Tandem events, one after the other in rapid sequence, produced a cumulative effect that made any single one of the interrelated and often confusing episodes less consequential than the aggregate picture, which in Washington was one of clear-cut North Vietnamese aggression. That of course is hindsight, a commodity that the civilians and military leaders making decisions on the afternoon and evening of August 4, 1964, could not possess.

| Critical U.S. Military Communications Three important August 4, 1964, communications on the Gulf of Tonkin situation motivated the Johnson administration to begin planning retaliatory action against North Vietnam:

Note the more than two-hour delay between the USS Maddox report of radar fixes and the time President Johnson was informed. In 1964 the military communications and intelligence system in Southeast Asia and the surrounding waters was primitive in comparison to what it became only two years later. Furthermore, the communications system in Hawaii and the Pentagon was only partially automated. Handling of flash precedence messages required some time-consuming labor, time that added to a growing backlog of both flash messages and messages of importance but of lesser urgency. |

Edward J. Drea is a regular MHQ contributor and the author of In the Service of the Emperor: Essays on the Imperial Japanese Army (Bison Books, 2003).

This article was originally published in the Summer 2004 edition of MHQ.

For more great articles, subscribe to MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History today!