[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n a popular war, it was an unpopular decision.

In late 1941 Hollywood leading man Lew Ayres became the first prominent American to refuse to fight. A renowned actor best known for his role as a soldier, Ayres had developed strong pacifist views and stood by those principles despite fierce public and professional backlash. The situation, coming just as the United States was readying for war, put the government in a precarious position—forcing it to take an unfamiliar stance and even bend its own rules.

BORN IN MINNEAPOLIS on December 28, 1908, Ayres had dropped out of high school to work as a musician. Discovered by a talent scout while playing the banjo and guitar at the Cocoanut Grove nightclub in Hollywood, he soon landed a role in the 1929 film The Kiss, opposite Greta Garbo.

The next year’s widely acclaimed film, All Quiet on the Western Front, launched Ayres into stardom. He portrayed Paul Bäumer—a sensitive and doomed German infantryman increasingly disillusioned with the horrors of trench warfare—in an earnest performance that, said the New York Times, made a “riveting impression on the moviegoing public.” The film packed a strong antiwar punch, and the entertainment journal Variety proclaimed: “The League of Nations could make no better investment than to buy the master print, reproduce it in every language for every nation to be shown every year until the word War shall have been taken out of the dictionaries.”

As a box-office attraction, Ayres hit stride in the late 1930s with his role as Dr. James Kildare in nine “B movies” that sometimes earned more than the studio’s major productions. Playing an idealistic young physician, Ayres became what the Los Angeles Times called “a household symbol across the nation, embodying everything that was good and decent and upstanding—and American.”

Despite his screen popularity, the reserved Ayres was an outlier in Hollywood circles. He admitted he was “never a great one for mixing with people” and, despite his profession, felt that movies were trivial in the grand scheme of things. “He’s a strange man, very strange,” fan magazine Photoplay proclaimed. His interests, too, were not standard Hollywood fare. He spent his time at his mountain retreat near Laurel Canyon, reading philosophy and religion, composing and playing music, and dabbling in astronomy and meteorology.

Once an avid hunter, Ayres abandoned the sport and became a vegetarian after a trip to Catalina Island, where a sow’s dying screams deeply disturbed him. They sounded almost human, he recalled. That experience, coupled with his study of many philosophies, including Christianity and Buddhism, as well as what he called “profound thinking,” led him to pacifism. “To me, war was the greatest sin,” he said. “I couldn’t bring myself to kill other men.”

But in late 1941, with war looming on the horizon, Selective Service Board No. 246 in Beverly Hills called on Ayres. The actor was willing to serve, but only in a noncombat role, and so he sought classification as a conscientious objector (CO). Requesting to go into the Army Medical Corps, Ayres, a certified first-aid instructor and active with the American Red Cross, wanted to help heal the wounds of war. “Don’t think I am trying to save my neck,” Ayres told the draft board. “I would like to be of service to my country in a constructive way and not a destructive way.”

But a CO classification was no sure thing. Draft board members, often World War I veterans, were notoriously unsympathetic to these claims, and Ayres’s views did not fit neatly within the legal definition. A CO’s objections to war had to have a religious basis. The courts and the Selective Service agreed that objections to “the futility or stupidity of war or on grounds of a social or merely humanitarian character” did not suffice.

For Ayres, who belonged to no organized religion and had no formal religious training, the stakes were high. Without a CO classification, he could be drafted and assigned to combat duty. To remain true to his principles, he would have had no choice but to refuse induction and face a five-year prison term.

After months of official deliberation—during which time the United States entered the war—Board No. 246 finally approved Ayres’s application in early 1942. Impressed by his sincerity, board member A. H. Pier described him as “quite a philosopher” who had “a kind of religion of his own.”

The board then had to decide which CO category was right for Ayres. Those classified as “I-A-O” were eligible for noncombatant military service, which would include the Medical Corps role Ayres had requested. Instead, the board inexplicably classified him “IV-E”—meant for those who objected to all military service—and assigned him to a civilian work camp in Wyeth, Oregon.

The public did not learn of Ayres’s classification until March 30, 1942, the day before he left for Oregon. With Hollywood stars like Clark Gable, James Stewart, and Henry Fonda already in uniform or soon to be, and others like John Wayne flying below the radar with draft deferments, the Ayres story made front-page news. Although he told the press he had asked to go into the Army Medical Corps, people focused on the actor’s refusal to take up arms and his IV-E classification. The blowback was immediate and fierce.

Variety labeled Ayres “a disgrace to the industry,” and Nicholas Schenck, president of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, declared him “washed up.” More than 100 theaters in Illinois refused to show his films, while the Fox Theatre in Hacksensack, New Jersey, stopped showing them after dozens of calls from angry patrons threatened a boycott. The army banned his movies from military bases, stating that soldiers “were not particularly interested in seeing the current pictures in which Lew Ayres appears.”

The general public reacted just as harshly. “I have a son in the Army as a private. Can you tell me why a ‘yellow dog’ like Ayres is any better than my son?” asked one angry draftee’s father. Businessman G. W. Mingus seethed, saying that when compared with Ayres, “Benedict Arnold was a Sunday school teacher.” Even the German-born Erich Maria Remarque, combat veteran and author of All Quiet on the Western Front, weighed in, albeit reservedly, saying, “I think we all should fight against Hitlerism.”

Others took a more sympathetic or neutral view. Wrote Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper: “It took courage—far greater courage—to do what he did than to wheedle and pull strings to get an officer’s uniform, as many, without the courage and ability to measure up to it, have done.” Director John Huston and actors Humphrey Bogart and Olivia de Havilland took out an ad in Variety to deny that the film community was ashamed of Ayres—although they were careful to repudiate his pacifism by calling it “the sad result of a sadder misconception.” An editorial in the New York Times called the whole Ayres controversy overblown. Pacifism, it said, “is a doctrine for the other-worldly and for saints, and there will never be enough of those to interfere with our war efforts.”

Ironically, it was a soldier, Private Eugene B. Crowe, who offered the staunchest support in a letter to Time magazine, writing: “Lew Ayres, instead of being detrimental to our public good, is indicative of what the American people wrote into their Bill of Rights and what we fight our wars about—the right to freedom in a democracy.”

THIS PUBLICITY CAUSED A STIR in Washington because the local board had obviously erred badly with their IV-E classification. Since Ayres was willing to serve in the Medical Corps, he should have been stamped I-A-O and sent to the army. To Selective Service director Lewis B. Hershey, it was essential to properly classify COs: every objector inducted into uniform freed a non-CO for combat duty, while every erroneous IV-E classification did the opposite.

But if the government could play the story the right way—painting Ayres as a “good CO”— it could encourage other objectors to serve as I-A-O uniformed noncombatants instead of in IV-E civilian work camps. Hershey immediately ordered the California board to consider reclassifying Ayres, and his office told the local board that the “widest possible publicity by you would have great morale effect on nation.”

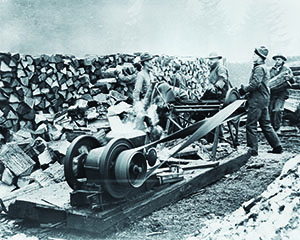

While the draft board reassessed his classification, Ayres reached the camp at Wyeth, Oregon, on April 1, 1942. Most of the 170 men in the camp did lumber work, clearing brush, felling trees, and cutting fire breaks. Ayres was assigned to first-aid work and was popular with the other men. The camp newsletter described him as “always friendly, often dogmatic, sometimes stagy,” while Chaplain Mark Schrock called Ayres “one of the boys.”

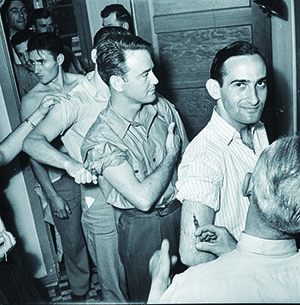

California Board No. 246 soon corrected its error and reclassified Ayres as I-A-O. On May 18, 1942, Ayres, “grinning and bronzed by the sun and wind,” as an AP story had it, was sworn in as a soldier in Portland, Oregon.

Like the Selective Service’s Hershey, the army recognized the publicity value of a celebrity CO serving in uniform and made sure the event got plenty of exposure and ink. Ayres told reporters that he was still a conscientious objector, but stressed that the Army Medical Corps was “the place I want to be—to be able to do some useful work.” Sent to Camp Barkley, Texas, for training, he told the press, “I hope they put me in a non-combat unit, but I can’t be sure they will.”

Actually, a Medical Corps assignment was a fait accompli, and Ayres knew it. The army could assign I-A-O soldiers to a variety of noncombatant jobs, not just medical ones. And although a soldier could not dictate where he would be assigned, Ayres had insisted that “the medical corps alone is the only branch of the service which could be commensurate with my ideas of conscientious approval.” With the government intent on selling him as the good CO, Ayres accepted his own brand of special celebrity treatment: a wink-and-nod assurance before induction that he would get the assignment he wanted.

Ayres finished his training on August 15, 1942, and the army gushed over him accordingly. Brigadier General Roy C. Helfebower, commander of the medical training center, called him an “excellent soldier” and said he felt confident Ayres would “render valuable service before his army career ends.” An unnamed officer added, “I wish I had a whole battalion of men just like him.”

Ayres, too, continued to play his part. “I have fallen in love with the medical department,” he said. “Everyone has been swell to me.” He was soon promoted to sergeant and made first-aid instructor at the camp. Army chow even added six pounds to his five-foot-10, 138-pound frame. But, growing restless with teaching and wanting to get his hands dirty, Ayres applied to go overseas. An opportunity arose that required a reduction in rank as a chaplain’s assistant; he took it.

In May 1944, Ayres landed in New Guinea. Assigned to an evacuation hospital, he counseled and comforted sick and wounded GIs. Two months later, Yank magazine reported finding a changed man. Sporting a mustache and graying hair, with his face lined and yellow from antimalarial medication, Ayres said that “it’s taken war to give me understanding of men and to find myself.”

His refusal to fight may have been a hot topic at home, but not overseas. “It was gratifying to have heard not one soldier say anything against what I chose to do,” Ayres said. His politeness, calmness, and willingness to help seemed to have won them over. Sam Dirienzo, a wounded GI with whom Ayres had worked, never forgot his kindness. “In your hour of need like that,” Dirienzo said, “it just reminded you so much of home.”

When American troops landed on Leyte in the Philippines on October 20, 1944, Ayres was with them and experienced the full horror of war. Leyte was a populated island, and civilian casualties were inevitable. The army set up an evacuation hospital in a centuries-old cathedral in Palo, near the site of the initial landings. The cathedral was soon flooded with wounded GIs and civilians. Cots for the injured reached as far as the altar rail; the baptistery became an operating room.

Ayres pitched in, and what he saw chilled him to the core. “I had imagined that war was a horrible thing. But it actually surpassed anything I’d dreamed of,” he said. “It’s bad enough in the field, where soldiers expect cruelty and death; but in cities, among helpless civilians, the picture is far worse.” He spoke of “what a bombed city looks like; or what it feels like to hold a child in your arms while it bleeds to death; or to stand by while kids watch their parents being dumped into a mass grave.” The most difficult task, he said, “is taking care of little kids with bullet holes in them.”

Ayres did his best, and he impressed all as “serious and helpful and friendly with everyone he meets,” a Life correspondent observed. “Everybody, including the Filipino children, calls him ‘Lew.’” Many Filipinos were avid moviegoers and were tickled to meet the “real Dr. Kildare.” Ayres got more of a thrill being recognized by the Filipinos than by people back home, he said.

When the fighting moved north to Luzon in January 1945, Ayres followed, but he contracted dengue fever, a serious tropical illness. His recovery was slow, and he finished the war as a staff announcer for the Armed Forces’ Radio Service station in Manila.

his wartime service

a changed man outside and in, but retained his pacifist views for the remainder of his life. (AP Photo)

IN THE FALL OF 1945, Ayres returned home to a public that was starkly different than it had been three years earlier. Americans were sick of war and its end was a relief to the country. The army’s favorable coverage of Ayres had likely had an impact, too; gone was the public vitriol of his refusal to take up arms. “Considerably thinner and much more mature in appearance,” noted the New York Times, Ayres “came back a hero in Hollywood’s eyes after meritorious service in the Pacific,” his more than three years in the army having “won the respect and admiration of his former detractors.”

Ayres, too, was changed. Military life had altered his world view. “I thought I could find my answer in books. The army changed that,” he said. “Mingling with men and seeing so much of reality, I got my head out of the clouds.”

He even developed a new appreciation for the power of cinema. “Why, I even became a fan myself,” he joked. Before the war, he had felt that filmmaking was “a silly business.” But while overseas, he saw the ability of movies to provide a distraction and even emotional support to war-torn minds; films could be a contribution, in their own way, to the war effort. “Stretch a screen across of couple of coconut palms, throw a picture upon it, and you get the whole gang out. That gave the boys what they needed—rest and a chance to get out of themselves. I think the same thing applies to the civilian world.”

Ayres returned to acting, but he never regained the leading-man status or box-office popularity he had enjoyed before the war. And he retained his antiwar views, but with a twist. Noting how much he learned “from associating with soldiers, of sharing a common lot and working toward a common end,” he felt that “other American youngsters might benefit in the same manner by serving a short hitch in a peacetime army.” He began to think that peacetime conscription might be a good idea.

“Fellowship among soldiers, with each man sharing his part of a common burden, is a wonderful thing to experience,” Ayres said. “Imagine what could be accomplished with such a singleness of mind and purpose in the civilian world.”

Lew Ayres died on December 30, 1996—best remembered for the soldier he played on screen and the one he refused to play in real life. ✯