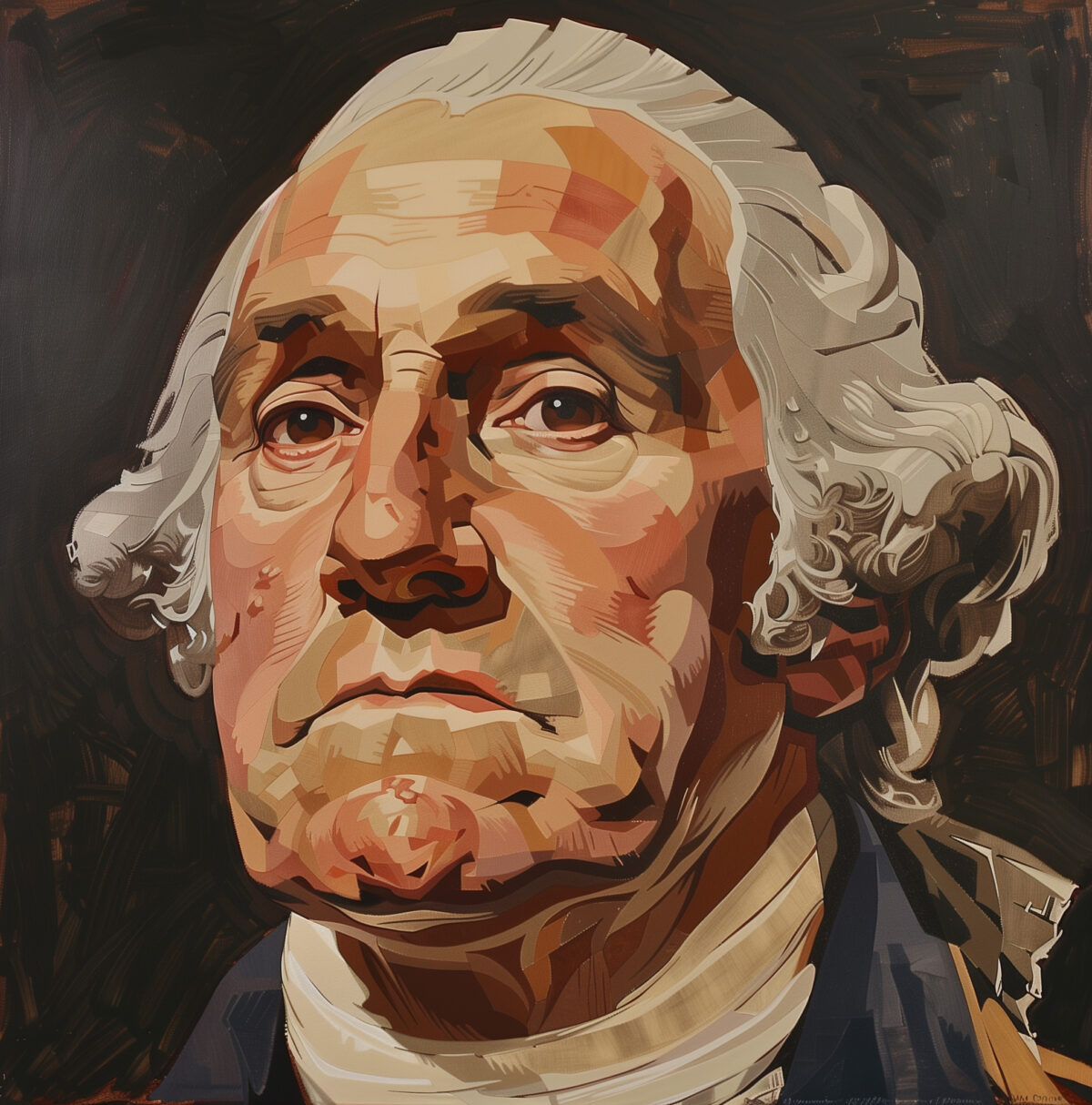

America’s greatest leader was its first. George Washington ran two start-ups, the army and the presidency, and chaired the most important committee meeting in history, the Constitutional Convention. His agribusiness and real estate portfolio made him rich. Men followed him into battle; women longed to dance with him; famous men, some of them smarter or better spoken, did what he told them to do.

What made Washington so great? He mastered the skill sets that every successful CEO, military commander or leader of the free world needs: problem-solving and organization.

1. When the world changes, change the world

Washington inherited Mount Vernon in 1761, and he expanded his acreage to grow the region’s most prized crop: tobacco. But his soil was poor, and Washington’s tobacco didn’t make the grade. Rather than sliding deeper into debt just to keep his coveted status as a Virginia tobacco planter, Washington diversified. He replaced tobacco with alfalfa, buckwheat, corn, flax and hemp. He began fishing the Potomac and exported the catches. Washington could have kept trying to wring new perfections out of an already perfected process. Instead, he tried a new world.

2. Understanding the power of the obvious

As commander in chief of the Continental Army, Washington ordered that camp latrines be dug and “frequently filled up to prevent their being offensive and unhealthy.” Obvious? Not to Washington’s soldiers, mostly rural men and boys accustomed to being casual about bodily functions. Washington decreed that inappropriate bowel movements were punishable by court-martial, and he kept a watchful eye on the battle for sanitation throughout the war. What is obvious to a leader may not be obvious to everybody; if it’s necessary for the health of your organization, then it’s necessary for you to keep after it.

3. Understanding the power of the un-obvious

Based on his previous military experience, Washington had a simple view of intelligence gathering: Send someone to observe the enemy and bring back the information. In 1776 Nathan Hale, a handsome young captain from Connecticut, volunteered to spy on the British in New York. He was arrested and executed within a week. Washington eventually authorized a network of agents who could spy while in the city on legitimate business. Only by unlearning his own experience and ignoring what seemed obvious to him did Washington become a skillful spymaster.

4. Delegate to innovate

Henry Knox, Washington’s artillery commander, had never fired a weapon in combat until the Battle of Bunker Hill. He’d dropped out of school at age 12, but became an expert on artillery from years of devouring military history. Washington trusted Knox’s abilities and sensed his potential. Knox soon proved himself an innovator. He added a company of artillery to every brigade of infantry to increase firepower. This also created all-weather infantry units: It was easier to keep cannons functioning in heavy rain or snow than muskets.

5. Control your flaws

Obstinacy is persisting beyond all reason. Washington lost New York in 1776 and spent the rest of the war plotting to win it back. By 1781 the fighting had shifted south, but Washington tried to convince his ally, the comte de Rochambeau, to take the city with a newly arrived French fleet. Rochambeau instead ordered his fleet to sail to Virginia. Once the new plan was in motion, Washington supported it with his usual energy and will to succeed. A few months later, he won the endgame at Yorktown. Washington was no less obstinate, but he could turn it off when the stakes were high enough.

6. Bringing out the best

In 1783, when his officer corps threatened to mutiny over a lack of pay, Washington turned a potential disaster into “the last stage of perfection to which human nature is capable of attaining.” He drew on their bond with him: You have known me all these years, and you should be as loyal as I have been. Men can make mistakes and choose wrong. They can also choose right. A leader must believe that there is some best to be brought out of a bad situation. Washington throws the burden of action on others and tells them that they can, and will, pick it up.

7. Working with troublemakers

Gouverneur Morris was a smart and accomplished aristocrat. He also was a pain in the neck. In 1792 Washington nominated Morris to be America’s ambassador to France but soon read him the riot act over charges of “levity and imprudence” and belittling those who disagreed with him. But Washington also praised his ambassador, expressing the “fullest confidence” in Morris’ ability to change. Morris promised to mend his ways, and he served well. A troublemaker who can be put to good use should be kept on. The gains can be worth it.

Originally published in the June 2008 issue of American History.