[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]They didn’t know what to make of him.[/quote]

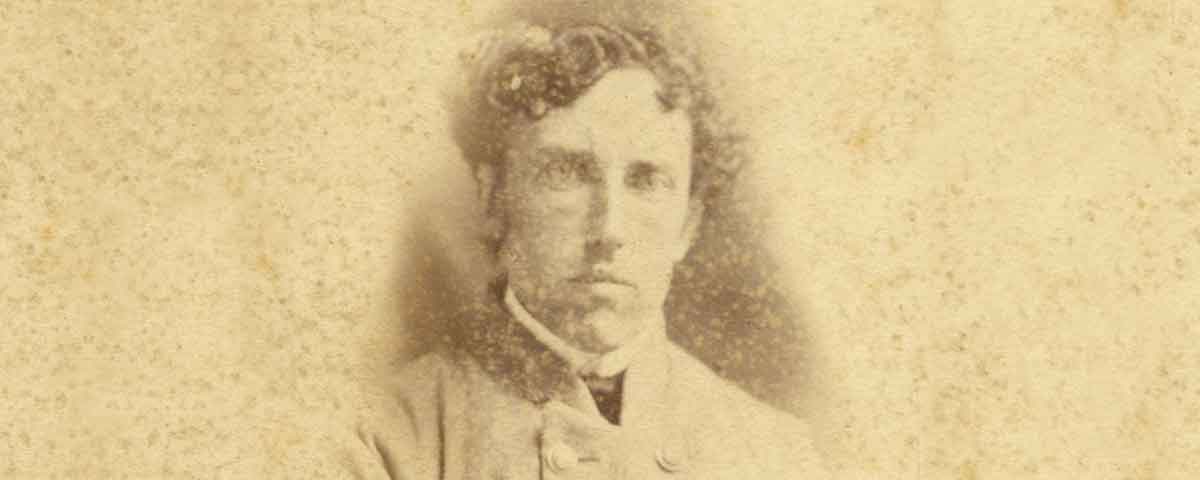

Unlike the other Confederate officers, this one had a European aristocratic bearing, something unfamiliar to these backwoods Texans. Even more intriguing was his name: Camille Armand Jules Marie, Prince de Polignac. Lacking fluency in French, the troops did not know how to pronounce his name, much less comprehend his noble origin. Instead of Polignac, they devised their own, less tongue-twisting sobriquet—Polecat, what they called a skunk. In jest, some of the soldiers held their noses in his presence. The prince took it all in good humor. After all, he knew prowess on the battlefield was what the Texans respected most. He wouldn’t disappoint them.

Before his arrival, Polignac’s command included some of the most undisciplined units from Texas. The 22nd, 31st, and 34th Cavalry regiments hailed from counties in northern Texas whose residents opposed secession before the war. Originally, their families had come to Texas from the nation’s border states. Most were wheat farmers with few slaves and little income to acquire them. Understandably, they were not enthused about the Confederate cause. Their mounts complemented their shabby appearance—unshod plow horses brought from home. Weaponry consisted of crude squirrel rifles unsuited for warfare.

On their first deployment to the Indian Territory, many of them were stricken with debilitating illnesses. Desertions increased accordingly, becoming a greater threat than the Union Army. The Confederate commander of the Indian Territory, Brig. Gen. Albert Pike, considered them a gross nuisance. He wrote, “I would have sent them over the Red River long ago, for part of them nearly crazed me.” During a heated exchange with one of their officers, he threatened to “shell them out of their camp.”

In Missouri, they saw action at Newtonia in September 1862, but that did little to help their reputation. Major General Thomas C. Hindman, commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, had finally lost patience with his unruly Texas cavalry; he took away their horses, forcing them to fight as infantry. In January 1863, a merger with the 15th Texas Infantry averted a mutiny at their Fort Smith camp. Now under the command of Colonel Joseph W. Speight, they were ordered back to the Indian Territory because of a lingering food shortage. Weakened by starvation, his men plodded through eight inches of snow, falling at an alarming rate along the way. Recalled Private Alfred T. Howell of the 34th Texas:

“By day, I limped along in my rundown boots, holes wearing into my feet. At night, my feet swelled and I could not stand. Men died every day. They laid themselves down. They would not move and they died. Men died on the wagons. From Fort Smith to the Mouth of the Kiamichi where we camped, our trail was a long graveyard.”

After a miserable winter camp near Doaksville, Speight’s frostbitten troops were ordered to Louisiana by Lt. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, named Trans-Mississippi commander in March 1863. Upon their arrival in Shreveport, Smith inspected his new brigade; his assessment was grimmer than Pike’s. Along with the continuing lack of discipline, a third of the Texans had no arms whatsoever. He wanted to completely dissolve the 22nd and 34th regiments and disperse them to more seasoned Texas regiments. Smith later changed his mind; he placed the two regiments in a drill camp established four miles from Shreveport by his aide de camp Colonel William R. Trader. Leaving two regiments behind, Speight led the 15th and 31st regiments south to reinforce the command of Maj. Gen. Richard Taylor. Teaming with Brig. Gen. Thomas Green’s First Texas Cavalry Brigade, they aided the capture of 453 Union troops at the September 1863 Battle of Stirling’s Plantation. But soon the troubled regiments received a new commander, Polignac, who would manage to bring out their best possible combat performance.

The Prince de Polignac was born to a noble French family on February 16, 1832, in Millemont, France. His father was a chief minister in the short-lived French court of Charles X. Young Polignac served as a lieutenant in the French army during the 1853-56 Crimean War. After his service, he traveled to Central America to study geography.

When the Civil War began, Polignac sided with the Confederacy, and served as a lieutenant colonel on the staffs of Generals P.G.T. Beauregard and Braxton Bragg. He saw action at the 1862 Siege of Corinth and at the Battle of Richmond, Ky., and was promoted to brigadier general in January 1863. In March, Polignac moved to the Trans-Mississippi Department, where Smith assigned him command of the brigade of unruly Texans. At first, they were not pleased with their new commander. Wrote Taylor:

“The Texans swore that a Frenchman, whose very name they could not pronounce, should never command them, and a mutiny was threatened. I went to their camp, assembled the officers, and pointed out the consequences of disobedience, for which I would hold them accountable; but promised that if they remained dissatisfied with their new commander, I would remove him.”

Polignac was fully briefed on the recurring deficiencies of his “problem brigade.” He immediately set about laboring diligently to improve the Texans’ morale and discipline. Their drilling complete, they followed him south to Simmesport, La. While there, they supported Confederate batteries shelling Union vessels on the Mississippi River. On February 7, 1864, the Texans tackled a more ambitious objective: a surprise attack on the Federal post at Vidalia. Brandishing his sword, Polignac exhorted his men, “Follow me! Follow me! You call me polecat, I will show you whether I am Polecat or Polignac!”

Federal gunboats fended off their attack, but not before Polignac’s men made off with 400 cattle, horses, and mules. More important, the Texans had gained a newfound respect for their General Polecat.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]‘follow me! Follow me! You call me polecat, I will show you whether I am polecat or polignac.’ -Camille Armand Jules Marie, Prince de Polignac[/quote]

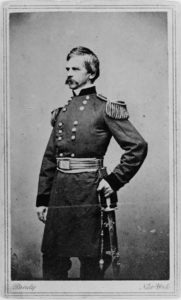

In March, Union Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks launched an ambitious offensive up the Red River, a key transportation route in the region. Supported by the ironclad fleet of Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter, 30,000 troops marched north from New Orleans or arrived south by steamboat from Vicksburg. Their objective was Shreveport, the headquarters of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department and a gateway to the valuable eastern Texas cotton fields. If Federal forces secured the region, cotton-

starved New England textile mills would again have access to an abundant source of the desperately needed raw material.

A combined naval and infantry assault forced the main Confederate Red River post, Fort de Russey, to surrender on March 14. Porter, along with Brig. Gen. A.J. Smith’s infantry, proceeded upriver to Alexandria, joining with Banks’ New Orleans troops. A second blow was dealt when Brig. Gen. Joseph Mower’s brigade surprised the campsite of the 2nd Louisiana Cavalry. About 250 cavalrymen were captured along with their horses. Fortune smiled but sprang a trick when Banks reached the village of Grand Ecore, La.

The river was too low for Porter’s fleet to proceed farther. Four days from Shreveport, Banks made the fateful decision to leave the protection of the fleet’s guns, advancing instead along a narrow, rutted stage road from Grand Ecore. The road wound through a dense pine forest with few clearings. To make matters worse, Banks encumbered his march with an immense supply train of 1,000 wagons. Timing was crucial; Shreveport had to be taken within a week or he would lose the services of Smith’s two veteran infantry corps, both on loan from Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s Army of the Tennessee. Upon reaching Natchitoches, Banks wrote confidently to Washington: “Our troops now occupy Natchitoches. We hope to be in Shreveport by the 10th of April. I do not fear concentration of the enemy at that point. My fear is that they may not be willing to meet me there.” All too familiar with Banks’ shortcomings, President Lincoln noted dryly upon learning of Banks’ communique from Chief of Staff Henry W. Halleck: “I am sorry to see this tone of confidence; the next news we shall hear from there will be of a defeat.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]‘Little Frenchman, I am going to fight banks here if he has a million men.’ -Maj. Gen. Richard Taylor[/quote]

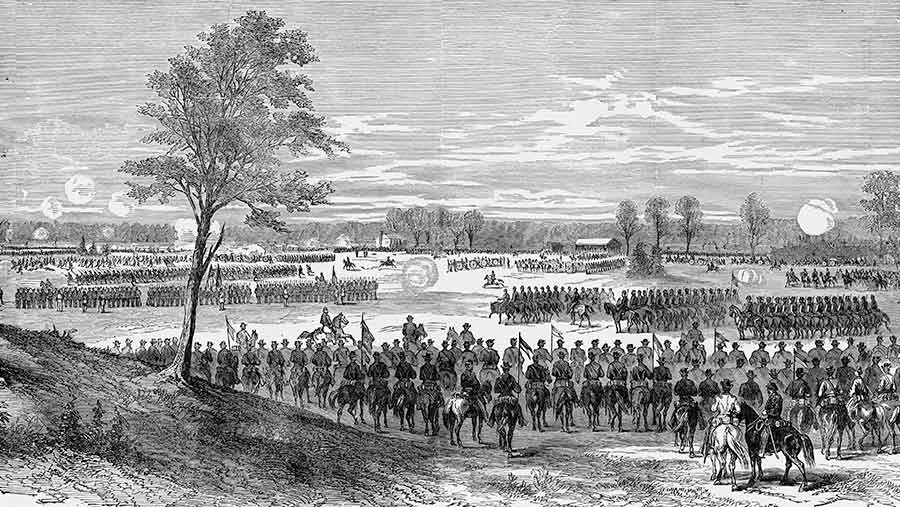

Meanwhile, Taylor retreated 200 miles in the face of Banks’ overwhelming numbers. Having learned tactics under Stonewall Jackson, he was anxious to go over to the offensive. He dispatched a note to Smith requesting permission to attack, later writing, “I would have fought a battle even against the heavy odds. It would have been better to lose the State after a defeat than to surrender it without a fight.” Even though he received no reply from Smith, Taylor decided to attack anyway. On April 8, he began forming his 5,300 troops at Mansfield, three miles south of Shreveport, in a line consisting of two divisions: Louisiana and Texas troops, under Brig. Gen. Alfred Mouton, on the left and Texans, under Maj. Gen. John G. Walker, on the right. Mouton’s Division, which included Polignac’s misfit Lone Star boys, would attack first. With the Yanks occupied, Walker was to follow with an attack on the left. Both divisions would act like a door hinge, crushing the Federals in between.

Banks’ dangerously extended column helped even the odds for Taylor. Out front was Brig. Gen. Albert L. Lee’s 3,500-man cavalry division, which soon came upon a Confederate force assembled in a clearing—much larger than Rebel units they had previously encountered. Lee requested reinforcements, and 13th Corps commander Brig. Gen. Thomas E.G. Ransom sent him two brigades. Under Colonel William J. Landram, they formed a line directly opposite Taylor. Alerted to the Rebel presence, the remainder of Banks’ force began marching toward Landram.

Tom Green’s Texas Cavalry Division slowed Banks with repeated attacks, buying precious time for Taylor to assemble and organize his men for the attack. Taylor told Polignac, “Little Frenchman, I am going to fight Banks here if he has a million men.” Yet he had only three hours of daylight left to attack. But better now, Taylor reasoned, while he still had a slim numerical edge. At 4 p.m., Mouton attacked Landram from the left. While smoking a cigar, Taylor calmly watched the action astride his horse. Advancing in echelon, Mouton’s regiments were met with a firestorm of musket and cannon fire. “The balls and grape shot crashing about us whistled terribly, and plowed into the ground and beat our soldiers down even as a storm tears down the trees of a forest,”one Louisiana soldier recalled.

A Rude Introduction

Two years before the Battle of Mansfield, Brig. Gen. Richard Taylor met Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks in battle in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. Commanding the Louisiana Brigade, Taylor served under the overall command of Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. The Louisianans were well known for their hard fighting and relentless marching. On May 25, 1862, Jackson’s troops forced Banks back to a defensive line just outside Winchester, Va., capturing so many wagons they referred to Banks as “Commissary Banks.” The Union right flank rested on Bower’s Hill just outside the town. Jackson ordered the hill be taken. With sword drawn, Taylor personally led his men on horseback. Watching the advance, Robert L. Dabney, Jackson’s chief of staff, wrote, “They marched up the hill in perfect order, not firing a shot! About half-way to the Yankees, in a loud and commanding voice that I am sure the Yankees heard, he gave the order to charge.” Taylor’s men took the hill, routing Banks from the field. Observing his soldiers fleeing through Winchester, Banks yelled out to them, “Stop men! Don’t you love your country?” A young private reportedly replied, “Yes, by God, and I’m trying to get back to it just as fast as I can!” Two months after his stunning success at the First Battle of Winchester, Taylor was promoted to major general and given command of the Department of Western Louisiana. –D.L.B.

By remaining mounted—and thereby offering irresistible targets to Union riflemen—Mouton and his senior officers were soon struck down, with Polignac assuming Mouton’s command. Walker had begun advancing on the right as the Federals battled Mouton’s assault. The Texans flanked the Union line, forcing a withdrawal. Three cannons were captured, then promptly turned on Landram’s men. The Union withdrawal quickly became a rout. Ransom was wounded in the knee and had to be carried from the field. Both of Landram’s brigade commanders were captured.

Landram’s fleeing troops plowed into a reinforcing column of 1,500 men under Brig. Gen. Robert A. Cameron. The 4th Division of the 13th Corps was swept away in the confused melee. Screaming the Rebel Yell, Taylor’s infantry was right on its heels. “Men found themselves swallowed up, as if it were in a hissing, seething, bubbling whirlpool of agitated men, who could not avoid the current,” wrote Private Frank M. Flinn of the 38th Massachusetts. “General Banks took off his hat and implored his men to remain…”

Unable to turn their wagons around on the narrow, tree-lined road, panic-stricken teamsters unhitched their horses and galloped away. Scores of prisoners, cannons, and abandoned wagons were scooped up in the wake of Taylor’s attack. At Pleasant Hill, Banks finally rallied his shattered column to hold off Taylor. Seeking the protection of Porter’s gunboats, he left the field the following day. Belatedly, Taylor finally got a reply from Smith on his earlier request to attack. Typically cautious, Smith urged him not to bring on a general engagement. Replied Taylor: “Too late, sir, the battle is won.” Thanks to the courage and fighting skills of Taylor’s force, notably Polignac’s Texans, Banks had been dealt a stunning defeat that led to a full withdrawal to Alexandria and an ignominious end to the Red River Campaign.

Fight Facts

Battle of Mansfield, LA. April 8, 1864

CAMPAIGN

Red River (March–May 1864)

Combined Union Army-Navy offensive up the Red River to capture Shreveport, La., headquarters of

the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department, and secure a gateway to eastern Texas cotton.

COMMANDERS

Confederate:

Maj. Gen. Richard Taylor (overall commander)

Maj. Gen. John G. Walker

Brig. Gen. Alfred Mouton

(replaced by Brig. Gen. Prince de Polignac after Mouton KIA)

Brig. Gen. Thomas Green

Union:

Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks (overall commander)

Brig. Gen. Thomas E.G. Ransom

Brig. Gen. Robert A. Cameron

Brig. Gen. Albert L. Lee

NUMBERS

Confederate:

5,000–14,000 infantry, cavalry, and artillery (disparity is due to large but unrecorded numbers of paroled Vicksburg Rebels joining the battle)

Union:

14,000 infantry, cavalry, and artillery

FORCES ENGAGED

Confederate:

Mouton’s Division (includes Polignac’s Texas Brigade)

Walker’s Division

Green’s Cavalry Division

Union:

4th Division, 13th Corps

3rd Division, 13th Corps

Lee’s Cavalry Division

ESTIMATED CASUALTIES

Confederate:

1,000 killed and wounded

Union:

694 killed and wounded

1,423 captured or missing

(Prisoners sent to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas)

OUTCOME

Confederate victory

Polignac’s unit suffered 213 casualties, and he was promoted to major general, effective June 1864. His grateful Texans, now under the command of Colonel James Harrison, presented their former commander with a fine horse. Polignac promised he would ride the “noble charger” across Texas after the war to visit them. In March 1865, however, he was sent back to France to drum up support from Emperor Napoleon III. The war ended before he could accomplish his mission.

Nevertheless, this was not Polignac’s last war. He remained overseas and rejoined the French army as a brigadier general. In the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War, he commanded a division in a losing effort that produced both a united Germany and the Third French Republic.

The Prince de Polignac died in Paris on November 15, 1913, aged 81. At the time of his death, he was the last surviving Confederate major general of the Civil War.

Donald L. Barnhart Jr., who writes from The Colony, Texas, is a regular contributor to America’s Civil War.