How CSS Stonewall became the Japanese Navy’s First Ironclad

Midshipman Alfred Thayer Mahan immediately recognized the ironclad ram he spotted entering Yokohama Bay in April 1868. He had seen it before, back when he was stationed at the Washington Navy Yard. It was the former CSS Stonewall, a French-built Confederate ironclad. Stonewall never fired a shot in anger during the Civil War, but had received a new lease on life as the first ironclad to serve in the Japanese navy.

“I have never known her subsequent fortunes in Japanese hands,” Mahan wrote in 1907, which is somewhat surprising. As a naval historian, Mahan later preached the vital effects of sea power. He would no doubt have been interested to learn that Stonewall, after being denied the chance to fight during America’s Civil War, played an important role in Japan’s.

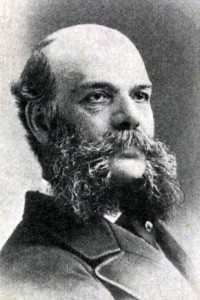

When James Dunwoody Bulloch was overseeing Stonewall’s creation, Japan was likely the farthest thing from his mind. As the Confederacy’s top naval agent in Europe, Bullock was determined to provide the South with ships. Born in Georgia in 1823, he joined the U.S. Navy in 1839 but resigned in 1853. In command of the U.S. mail steamer Bienville in New Orleans when war broke out in April 1861, Bulloch resisted pressure to surrender his vessel to the Confederacy and fulfilled his responsibility to its owners by sailing back to New York. Then he offered his services to the Confederacy and made his way to Montgomery, Ala., to meet with the secretary of the Confederate Navy, Stephen Mallory. The South lacked the resources to make warships, and Mallory asked Bulloch to oversee their construction in Europe. Agreeing to do so, Bulloch traveled to Canada and sailed to Liverpool, arriving on June 4, 1861.

But Britain had declared its neutrality in May and wasn’t about to allow the Confederacy to use it as an arsenal, especially with American minister Charles Adams quick to protest any perceived tilt toward the South. Bulloch’s main hurdle was Britain’s Foreign Enlistment Act, passed in 1819 to make it illegal for British subjects to build, arm or crew warships for belligerents in foreign wars. Guided by a Liverpool solicitor who, Bulloch said, “piloted me safely through the mazes of the Foreign Enlistment Act,” the Rebel agent stuck close to the letter of the law when he commissioned the vessels that would become Florida and Alabama, plus two armored rams from the Laird & Son shipyards of Birkenhead, across the Mersey River from Liverpool. The English shipbuilders ostensibly had no idea of their creations’ final destinations, and Bulloch arranged for the ships to receive arms and Confederate crews outside of Britain.

Adams knew perfectly well what was going on, however, and Bulloch’s activities brought additional scrutiny from private detectives. As pressures increased in England, Bulloch turned his eyes to France. That country had issued its own neutrality proclamation in June 1861, but Bulloch believed the French would follow the whims of Emperor Napoleon III, who appeared to favor the Confederacy. France craved Southern cotton, and a weakened United States would be less likely to interfere with Napoleon’s ambitions in Mexico.

In 1862 French officials, including the emperor himself, let Confederate diplomat John Slidell know that France would not interfere if the South built warships at its shipyards. Slidell communicated that welcome news to Bulloch. By March 1863, the Confederate government was on the verge of receiving a $14.6 million loan backed by the sale of cotton bonds in Europe, so Bulloch traveled to Paris that month to meet with Slidell and French shipbuilder Lucien Arman. Arman assured Bulloch that when the U.S. government made its inevitable protests to France, he would say the ships were designed for trade in the Pacific for either the Chinese or Japanese governments, and had been armed as protection against pirates.

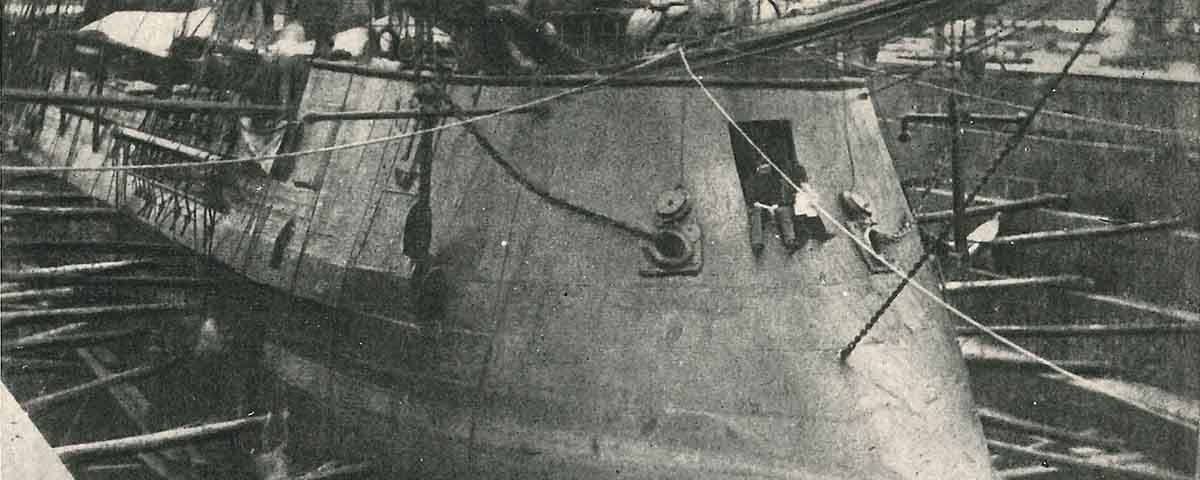

Bulloch placed an order for four 1,000-ton, steam-powered corvettes. On July 16, 1863, he commissioned construction of two ironclad steam-powered rams, each just under 172 feet in length, with a 300-pound turreted gun on the bow and two 6-inch rifled guns astern. Twin screws allowed for rapid turning. Projecting from each ship was an iron ram, which Bulloch hoped would wreak havoc on the Union ships blockading Southern ports. Since he wanted the rams to operate on the South’s coasts and rivers, the vessels would have a light draft, though that would limit their seaworthiness.

But the tides were already turning against the Confederacy, shaking French confidence in the Southern cause. Bulloch soon sensed a shift in the diplomatic winds. Construction of the ironclads—known as Cheops and Sphinx to underscore the fiction that Arman was making them for Egypt—had started at a good pace, but work appeared to be slowing.

Making matters worse for the Confederates, in the fall of 1863 William Dayton, U.S. minister to France, received stolen papers from the Nantes shipyard that was building two of the corvettes, providing incontrovertible evidence that the rams were intended for the Rebels. Dayton protested to the French, who notified the shipbuilders they must find new customers for the corvettes and the ironclads would not be allowed to leave France.

Bulloch remained hopeful that at least one ram would eventually serve the South. Arman advised the American that the sale of one ram to Sweden should ease U.S. suspicions, after which he could contrive to deliver the second ram to the Confederacy. Arman also said he would meet personally with the emperor within two weeks and discuss arrangements. Bulloch felt “a reasonable assurance of seeing one of our rams at work upon the enemy.”

That sense of assurance was soon dashed. Arman’s meeting with the emperor did not go well. Napoleon reportedly ordered the ships sold at once. Bulloch seethed over what he saw as French perfidy.

Peru bought two corvettes. Prussia bought the two Bordeaux corvettes and one of the rams. Denmark bought the other—the future CSS Stonewall—but that sale was delayed until Denmark’s ongoing war with Prussia ended. By then, however, the Danes were suffering from buyer’s remorse. Once the ram reached Copenhagen in November 1864, Arman had an agent ready to begin negotiations to sell the vessel to the Confederacy.

Bulloch, hoping to see his ironclad break the blockade of Wilmington, N.C., or perhaps attack General William T. Sherman’s supply depot at Port Royal, S.C., began recruiting a crew for the vessel, now called Olinde. For commander he picked Captain Thomas J. Page, who had come to Europe to command one of the Birkenhead rams and remained at loose ends after Britain seized those two ships in October 1863.

In London Bulloch hired a tender, renamed City of Richmond, and assigned Lieutenant Hunter Davidson to command it. In Paris Commodore Samuel Barron rounded up more officers, 17 of whom had previously served aboard Florida, and arranged to have them sail to England and join Davidson on City of Richmond for its rendezvous with their new ship. Bulloch worried the men would be detained in England, but British authorities made no moves to hold them.

On January 4, 1864, Bulloch wired to his Copenhagen agent, “Sail as soon as you can.” His plan called for the ram to steam to Niewe Diep, in the Netherlands, for coaling and then head for Quiberon Bay in Brittany to rendezvous with City of Richmond. Juggling all those complex arrangements was difficult enough, but now Bulloch also had to suffer the whims of nature. Almost as soon as the ironclad left port, a fierce storm forced the vessel’s crew to shelter at Elsinore, Denmark. City of Richmond left London on January 11 without incident, but a storm forced the little paddle-wheeler to seek refuge in Cherbourg, where it remained until January 18. City of Richmond finally made it to the rendezvous point on January 20. Four days later the ironclad—now officially named CSS Stonewall—finally hove into view, “to the rapturous delight of all who were in on the secret,” wrote Davidson. But the ship had suffered terribly from the ocean’s pounding. It was filthy and had developed a leak around its rudder casing.

On January 28, the two vessels left for San Miguel despite more severe weather. Davidson reported that “Stonewall would often ship immense seas…but yet she never seemed to be injuriously affected by them….” The leak, low stores of coal and an unhappy crew persuaded Page to head for Ferrol, in northern Spain. Meanwhile Davidson, aware that delays had already cost him one moonless window for running the blockade, opted to head out across the Atlantic. The two ships parted ways on January 30.

The Spanish authorities at Ferrol were willing to help—until Horatio J. Perry, the U.S. chargé d’affaires in Madrid, heard about Stonewall’s arrival. Perry reportedly felt “forced to use firm language” with the Spanish government to have all repairs halted. But the ship’s officers were also unhappy, complaining to Page about the vessel’s condition and the unlikelihood it would be able to make it across the Atlantic. The captain departed for Paris to meet with Bulloch and Commodore Samuel Barron to get advice. Bulloch promised to send an engineer to deal with the ship’s shortcomings.

More bad news arrived when the frigate USS Niagara, commanded by Commodore Thomas Craven, reached the area on February 10, soon joined by USS Sacramento. “The Stonewall is a much more formidable vessel than any of our monitors,” Craven reported on February 28. “In smooth water and open sea she would be more than a match for three such vessels as the Niagara. In rough weather, however, we might be able to annoy if not destroy her.”

Repairs completed, Stonewall finally steamed away from Ferrol on March 24. To make sure no fighting broke out until the belligerents were in neutral waters, a Spanish vessel escorted the ship to some distance, then returned to port. Steaming up and down across a perfectly smooth sea, Stonewall waited for battle, but the two American ships nearby at Coruna never weighed anchor. “This will doubtless seem as inexplicable to you as it is to me, and to all of us,” Page wrote to Bulloch. “To suppose that those two heavily armed men-of-war were afraid of the Stonewall is to me incredible, yet the fact of their conduct was such as I have stated to you.”

Craven viewed the situation differently. “With feelings that no one can appreciate, I was obliged to undergo the deep humiliation of knowing that she (the Stonewall) was there, steaming back and forth, flaunting her flags, and waiting for me to go out to the attack,” he wrote to Perry in Madrid. “I dared not do it! The condition of the sea was such that it would have been perfect madness for me to go out. We could not possibly have inflicted the slightest injury upon her, and should have exposed ourselves to almost instant destruction—a one-sided combat which I do not consider myself called upon to engage in.”

Unable to entice his adversaries into a fight, Page set course for Lisbon. There the Portuguese authorities made him feel “that he was the representative of a losing cause.” He refueled and continued to the Azores. From there, he first set course toward Bermuda, then Nassau and finally to Havana, where he learned of Robert E. Lee’s surrender.

Page then agreed to surrender his ship to Cuba if the authorities would pay $16,000 so he could pay off his crew. The Cubans wanted him to ask for more, knowing they would eventually be reimbursed by the Americans. On May 19, Page turned Stonewall over to Cuba, and it was subsequently handed over to the United States for $18,064.01, Page’s original figure plus expenses. After waiting out a yellow fever epidemic, an American crew sailed the ex-Confederate ship to Washington. On the way Stonewall collided with and sank a coal schooner in Chesapeake Bay.

Craven was also in Washington at the time, facing a court-martial for failing to destroy Stonewall. He was found “guilty of the charge in a less degree than charged” and sentenced to two years of paid leave. That displeased Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, who felt the decision was “an unsuccessful attempt at compromise” between those who believed Craven was guilty and those who didn’t. Welles set the proceedings aside and had Craven relieved from arrest.

Stonewall would have to steam to the other side of the world to fight. When Commodore Matthew C. Perry had visited Japan in 1853 and forced an American “open door” policy on the isolationist island nation, he set off a chain reaction that pushed Japan into the modern world. The Japanese were impressed by Perry’s modern tools of war and became determined to upgrade their own navy. When a Japanese purchasing mission toured Washington’s navy yard in 1867, the guide, Commander George Brown, pointed out Stonewall. The Japanese bought the vessel for $400,000 and hired Brown to pilot it back to Japan.

Stonewall made the journey via the Strait of Magellan and then up to Hawaii and across the Pacific to Yokohama. The ship reached Yokohama when Japan was near the end of its own Civil War, which had pitted the feudal lords of the Tokugawa Shogunate, who had ruled Japan since 1603, against the forces aligned with the emperor, Meiji Tenno. The emperor’s forces captured the capital of Edo (Tokyo) in 1868, but Admiral Takeaki Enomoto and his followers continued the struggle for the Shogunate from a naval base on the northern island of Hokkaido. The flagship of their rebel fleet was Fujiyama, a U.S.–built steam corvette that the Japanese had received in January 1866. The 207-foot, 1,000-ton vessel was powerful by Japanese standards, but it had a wooden hull.

The purchasing mission that had arranged to buy Stonewall had been dispatched by the Shogunate, but the U.S. government—professing official neutrality—initially refused to release the vessel to the Shogunate once it reached Japan. The American minister in Japan waited until January 1869 to release the ironclad to the Imperial forces, which renamed it Kotetsu. Two months later Admiral Enomoto, determined to capture the powerful ship for his Shogunate navy, dispatched a paddle-wheeler called Kaiten in an attempt to capture the enemy ironclad, but Kotetsu’s defenders managed to drive them back with a Gatling gun and killed Kaiten’s captain.

The emperor’s forces struck back on May 11 at the Battle of Hakodate. Led by Kotetsu, a squadron of Imperial ships swept away a rebel fleet and leveled the shore defenses with their guns. “The last rebels surrendered and the Meiji regime triumphed, with the former Confederate vessel a significant factor in the victory,” according to historian William L. Neumann.

The former Stonewall remained a formidable weapon for the forward-looking regime of the Meiji Restoration. As early as 1869, the American minister issued a warning that the Japanese, emboldened by their new naval strength, “perhaps entertained a conceit that they were strong enough to defy our government.” The former Confederate vessel would remain a part of the Japanese fleet until 1888.

Japan meanwhile continued to modernize its navy. Early in the next century Japanese forces succeeded in demolishing the Russian navy during the Russo-Japanese War. In one of history’s strange ironies, the peace treaty between Russia and Japan was brokered by President Theodore Roosevelt—the nephew of James Dunwoody Bulloch, whose work had inadvertently helped send Japan down the path to a modern navy.

Tom Huntington, former editor of American History and Historic Traveler magazines, is the author of Searching for George Gordon Meade: The Forgotten Victor of Gettysburg (2013).