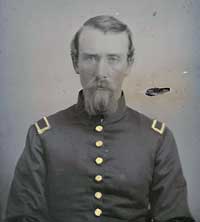

‘A Rebel Batery Unlimbered and Opened on Us’

Union Lieutenant William M. Reid recounts the Battle of Shiloh

On April 6, 1862, the first day of the Battle of Shiloh, William M. Reid of the 15th Illinois Infantry scrawled in his diary: “All day we fought the Rebels but had to give way; we disputed every inch of ground. Lost four killed and sixteen wounded out of company….” The entry gave little hint of what the second lieutenant had seen during one of the war’s great bloodbaths. Reid’s regiment had rushed to shore up the Union right flank collapsing under the pressure of a Confederate surprise attack. His regiment was constantly on the move for hours as the battle roared through the woodlots and hollows along the Tennessee River. Reid saw his regimental commanders, Lieutenant Colonel Edward Eliis and Major William Goddard, killed along with dozens of his comrades. During the desperate fighting, he picked up a musket and fought as a private. After the war, while his memory was still fresh, Reid detailed his harrowing wartime experiences in a journal now preserved along with his diary at the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. His account of Shiloh follows with minimal editing and added paragraph breaks. Spelling has been corrected in some places for clarity.

On April 6, 1862, the first day of the Battle of Shiloh, William M. Reid of the 15th Illinois Infantry scrawled in his diary: “All day we fought the Rebels but had to give way; we disputed every inch of ground. Lost four killed and sixteen wounded out of company….” The entry gave little hint of what the second lieutenant had seen during one of the war’s great bloodbaths. Reid’s regiment had rushed to shore up the Union right flank collapsing under the pressure of a Confederate surprise attack. His regiment was constantly on the move for hours as the battle roared through the woodlots and hollows along the Tennessee River. Reid saw his regimental commanders, Lieutenant Colonel Edward Eliis and Major William Goddard, killed along with dozens of his comrades. During the desperate fighting, he picked up a musket and fought as a private. After the war, while his memory was still fresh, Reid detailed his harrowing wartime experiences in a journal now preserved along with his diary at the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. His account of Shiloh follows with minimal editing and added paragraph breaks. Spelling has been corrected in some places for clarity.

On the way up the Tenesee River we passed the ruins of the Louisville & Nashville RR. Bridge, also that of a steamer the rebels burned after the surrender of Ft. Henry….many places we saw where the gunboats had battered down log houses, or cut off trees, undoubtedly when confederates had fired on our boats—We were truely in Dixie and geting where confederates lived.

As we aproached the landing at Pitsburg, the gunboats shelled the woods, and took every precaution against masked batteries. Then our regiment landed, and soon found ourselves in a densly wooded country interspersed with ravens, and scattered cotton fields; and small log houses here and there.

We marched about half a mile from the landing and pitched our tents, and made ourselves at home; others soon was destined to be one of the hotest battles of the war. I was, and had been for quite a time in command of the company.

Rogers being at St. Louis and Pratt being home sick. We drew new Sibly tents here, and were very comfortable.

From the time we landed on the 17th of March 1862 our cavalry were more or less engaged with the enemy and scarcely a day passed without some fatalities.

Troops continually arive and hospitals are being put in order; drill occur diely [daily], and all indication point to some important occurance in the near future—Andso the time drifted along until Friday the 4th of April, when our attack was made on a reconoitcing party, and we were sent to its support—But the enemy evidently only wanted to find out our strength, and where we were, and fell back after a slight skirmish.

The morning of April 6th Sunday, Dawned like a day in June at home. The trees were nearly in full leaf, and the woods were full of spring flowers. We had just got our breakfast, when our attention was atracted to a distant roar like the lake in a stormy November day. Knowing that we would be called on soon, our band struck up the long roll, and the companies fell into line in their company quarters, and marched out to the regimental line, and stood ready for orders; it came soon as an aid come riding with orders for Lt. Col. Ellis commanding.

We took the road behind Waterhouse’s Chicago Battery—and away we went to the front, where the roar of the action was now at its highth—Our brigade [Col. James C. Veatch commanding] had been sent to the support of Sherman, and to fill a breach on his right. Soon we got to our place across the main road to Corinth; the batery unlimbered; our regiment put on their bayonets, and laid down on their faces behind the battery. We had not long to wait; the battery in our front opened, firing over a raise, and to the front often varying their aim to the right or left, as they saw troops massing; soon the batery-men began to fall, shot by riflemen from the front.

A rebel batery apeared on their from the right and front, and shell and shot, flew over head like hail—It seemed to me as if the batery was being all cut to pieces, when sudenly four horses hitched to a cason [caisson] ran away and came down the road straight for my company. I spoke to the men and told them to give them the bayonet; they rose up presented the still [steel], and the frightened horses went around the right of the regiment. By this time too, batery had all gone to pieces, the men mostly killed. Then a regiment on our right broke and ran; this let the enemy into a space on our right; still the men laid firm. Mini[é] balls now began to come thick and fast, Lt. Col. Ellis fell, dead Major Goddard took his place to fall killed that moment as soon—Capt. Wapin went the same way. The confederates came over the brow of the bluffs about fifteen rods in our advanse, and planted their flag between two of the guns left by the baterymen.

Then we opened on them, we were firing them buck shot and an ounce ball to a charge, and at that short range proved very effectual. The southern men disappeared from our front, but those coming in on our right now began a cross fire, and soon the ground was covered with dead and dying.

One of our sargents got a ball in the forehead, and the blood flew all over me; he and I thought him dead, and did not know but that he was until I saw him some half hour afterwards, with a handkerchief around his head, fighting with the rest of the men—Seeing that we could no longer hold this ground, our officers commanded a retreat, and every man jumped for a tree. The firing now was something fearful, one could not see a rod away or hear eaven [even] a fiew [few] feet from ones his face. I got about eight of my men, and the U.S. Flag, and helping the wounded as much as I could got out of range. Some half a mile in the rear I found a line forming for another stand, and fell in with some men of the 17th and other regiments—Soon a rebel batery unlimbered and opened on us.

And here I must pause to describe one of the finest artilery duels I ever saw—This confederate batery was a long range rifle one, and rang like a crash of lightening every time it went off at the far end of the cotton field. Near us was a plain looking smooth bore twelve pound Union battery of all Germans. An aid came and ordered this Dutchman to silence the rebel batery. Does the local know I have only smooth bore guns? Asked the Dutchman. That is your orders said the aid, “Pal” said the Dutchie. I do the best I can. Then turning to his men he spoke German for about a moment.

Two guns of the German batery took each side of the field keeping close to the fence, while we infantrymen took the woods on either side to support them. Away went Dutchie’s at a galope, and soon were close onto the rebel batery, which had made so much smock [smoke] they did not see the Dutchman coming. Whirling his guns into position and double-shooting them with canisters he opened on the confederates; and in about four rounds each had completely torn the rebel batery to pieces. It seemed to me that there was not a man or horse left. Then limbering up the guns he flew back up the cotton lots, which we kept the infantry from following him. I have seen many fights since, but nothing to beat this.

All day long, on that eventful Sunday, did we fall back from our line to another, until we found ourselves, a mere squad in what is known as the hornets nest, when all the afternoon we was in the smock of the battle, hungry, thirsty, and tired almost to death.

How often they charged our position! How often we repulsed them! Until Albert Sidney Johnson fell late on Sunday afternoon; then [Union General W.H.L.] Wallace fell and his brave Iowa boys, (and they were mostly boys) fell back, until at five o’clock we were but a mere remnant around Webster’s heavy guns at the river bank, near when we were camped in the morning. During the day I had been allmost the entire length of the line, and often in no command at all. I had seen colonels of cavalry, and Majors of Artilery, fighting as privates in infantry, with muskets and bayonets. I had myself, in the early forenoon picked up a Springfield rifle and cartridge box, and used it through the entire fight afterwards. Right closed with a desperate charge of the New Orleans Guard, and some assisting regiments, through our former camp they advansed with our flag, and being clothed in dark colors, got near our line before they threw down our flag and raised their own. The big guns opened on them, and the flanking infantry and they were repulsed, with fearful loss. In the malee our new sibley tents were completely ruined; being in the midst of this attack. They looked like sives after the fight. So closed the Sunday’s battle—

On Monday Buell took the advanse, and though we were often under fire, did not get into a very hot time, until Monday afternoon when Sherman’s regulars, had failed to dislodge the enemy from a position on our right. Gen. Grant seeing the repulse of the regulars headed a charge of the 14th & 15th and we carried the position—But I anticipate, with the close of Sunday’s fighting, and the coming of night

I crawled into a vacant tent, and got some sleep. The rain fell in torents; and came through the bullet holes in the tent, and I changed often to keep partly dry. The ground around the landing was filled covered with wounded, who had accumulated during the day, faster than the surgeon could attend to them; and their moaning caused many a tired soul to lay awake in sympathy. Our field officers had all been killed the day before; and so we had Lt. Col. Lealin of the 14th assigned to command us, and he did so all day on Monday. The confederates…by Monday night were in full retreat. I think I saw nearly the last of them about four o’clock Monday—I was out with a skirmish squad, and a man on a white horse, commanding a detachment of rear guard of the confederates was retreating up a long cotton field—I heard him give his commands, as plainly as our own officers—forward guide center march, we crowded to the fense and began firing at him; his artilery unlimbered, and gave us canister; when that did not stop us, he sent his cavalry after us. We rallied by sections and repulsed the cavalry, under cover of this movement the whole command of confederates disappeared into the woods. And so ended the great battle of Shiloh, great in its results; great in casulties of my regiment the regt. lost 255 killed 8 wounded and company. In our company we lost 6 killed and sixteen wounded, some of the wounded were terably so. We had fifty men in the morning of Sunday, and lost 22 killed or wounded. Among the officers of the regiment we only had 2 captains and four lieutenants capable of duty—Both the Capt’s had bullet wounds holes through their caps. We remained on the field until after dark on Monday, and then went back to camp—to find it full of dead and wounded confederates, left from the fatal charge they made on Sunday afternoon. We managed to get them out of the way so we could lay down, and slept quite well with the dead and wounded all around—I thought I had seen shocking sights at Donaldson [Donelson]; but it did not compare with that of Shiloh. The ground in many places for half a mile was so thick with dead men one could walk the entire distance and step from one to another. On Tuesday morning we gathered our dead together and buried them in a long trench close to the camp, Col. Ellis at the head; after him the officers according to rank, and the men in regimental order; just as they had marched out to battle that glorious Sunday morning only a fiew days before. I was detailed on Wednesday to take charge of a burial party to take care of the confederates, and it was a big job. We were not quite so careful of them—A long trench about twelve feet wide and five or six feet deep was dug; government waggons were hauling them to the place, while some men were packing them into the trench, until nearly full, then the dirt was rounded over them. The dead horses was next looked after; and there were hundreds of them. Wood was piled on them, and set fire; if a horse was pretty fat he would burn; but if lean he would only half burn. The balance would lay them, and soon, the whole country smelled like a tan yard.

I was glad when after a week or ten days we were ordered to move to the front on toward Corinth. One had but little idea of the amount, of wreckage there is left on a battle field. It took a week to pick up the abandoned arms, and cannons left at Shiloh, and I don’t know how many boats to take it north, we recaptured almost all the guns they got of us Sunday, and many of their own. I saw many cannons marked, captured from Army of Potomac at this or that battle—Also one that belonged to the Washington Artilery of it a captured by this organization them from Mexicans at Monte Ray [Monterrey]….You can immagine they would never have left it if possible to save it.

I want to say one word here as to the attack at Shiloh being a surprise. It might not have been so to the Generals; but it certainly was to the men whom I saw running to the landing carrying their pants in their hands; and many others in various disable condition, as late as when we were going out to take our place at the front—now began the advanse on Corinth. Every day there was fighting at the front; often amounting to small battles. That at Monte Ray being quite severe. Gen. Hallock had assumed command, and adopted a conservation policy, and made the men throw up fortification in the heavy timber at every move; and get up every morning before daylight, and stand to arms until he was satisfied the rebels was not going to attack him. all this time the Johnnie’s are falling back on Corinth and fooling the old men of the mountains. so we proceeded until we got where we could see that they were evacuating the place, and hear the whistle of the engines on the Memphis & Charleston RR. Pope was stationed on the left and could see the movement, and we could hear the thunder of his big guns, as he tried to stop the movement. It came to a day when I was out to the front with skirmishers, and lost a man from Company “B.” The confederates were very active, and seemed to have an extra amount of men at the front 15. The next day all had left the works, and I went into Corinth without opposition—Our old man Hallock had been outwited and Beauregard had gone back to fight in the eastern army. I don’t know of so punile a campaign as that from the Landing to Corinth. If they had let Grant alone, or given Sherman the command the confederate army under Beauregard never would have gone back east again. As it was Pope followed the remnants of the army south a ways, and then came back to look at one another.”

For another Union perspective, click here.

For a Confederate perspective, click here.

Article originally published in the April 2012 Civil War Times.