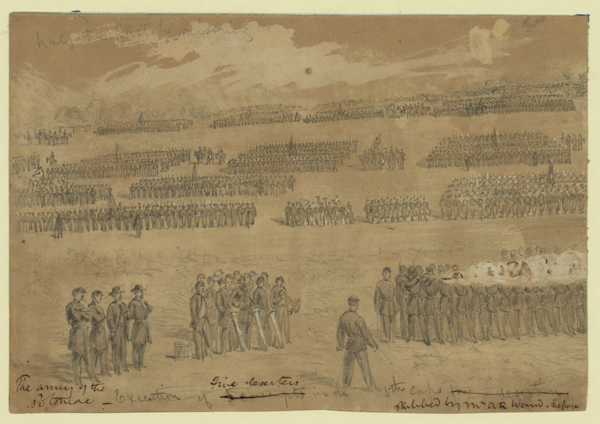

In his 1912 memoir War Stories, former Confederate soldier Berrien M. Zettler described witnessing the December 9, 1861, execution of two members of the Louisiana “Tiger Rifles”—two soldiers who had “overpowered” an officer and threatened to kill him, for which “they had been court-martialed and condemned to be shot.” According to Zettler, the execution attracted a crowd of roughly 15,000 men, so many in fact that “the sentinel threatened repeatedly to put his bayonet into those of us in front if we did not stand back.” It was a spectacle that most would not soon forget.

The prisoners arrived in the same wagon that carried their coffins. The crowd formed three sides of a hollow square, with the square’s open side containing two posts measuring about two feet above the ground, approximately 30 feet apart. The prisoners’ hands were tied behind them, and they were blindfolded and tied to the posts. A detail of 12 men then marched in front of the prisoners. The officer in charge raised his hand, signaling the detail to lower their weapons “to the position of aim.” Even after 60 years had passed, Zettler still recalled the execution that day as a “very sad sight and one that deeply impressed me.”

Zettler’s profound reaction is echoed in numerous letters, diaries and memoirs of soldiers, many of whom said that public executions seemed more horrific to them than the carnage they had witnessed on battlefields. Accounts of wartime executions, however, can tell us much more than how men reacted to seeing comrades publicly put to death. A closer look sheds light on a host of important questions, including the relationship between battlefield and home front, morale and nationalism.

The Articles of War enacted by Congress in 1806 were used by Federals and Confederates alike to govern behavior. Most cases of insubordination, such as drunkenness, were dealt with at the company or regimental level. General courts-martial at the brigade level or higher dealt with more serious crimes. But the ultimate punishment was death by execution.

Most of the executions described in this article were carried out as punishment for desertion, which constituted a serious threat to the overall cohesiveness and effectiveness of an army. They were often staged events—observed by hundreds and sometimes thousands of troops—intended as a warning to the offenders’ comrades in arms. In wartime letters, some Confederates provided detailed accounts, often relating particulars such as last words and final prayers. Such attention to detail attests to the emotional and psychological impact they had on their audiences, especially in the early stages of the war.

For those who witnessed the December 1861 execution of the Louisiana Tigers from Roberdeau Wheat’s battalion, the notable attention to detail in their accounts reflects the novelty of the event. Writing just a few days later, 1st Lt. William R. Elam of the 18th Virginia Infantry recalled the size of the crowd: “I was one of about fifteen thousand in number to witness a few days ago, the solemn sight of two “Soldier[s]” being shot.” Z. Lee of the 19th Virginia, who was also in attendance, recalled watching soldiers “moving on over the hills from sun up to 12 o’clock (the hour of execution). “Every hill…presented the appearance of a swarm of bees.” Elam also noticed that the “trees of the adjoining woods were crowded as if by wild Pigeons.”

Onlookers often commented on how condemned men arrived at an execution site, as well as the entourage accompanying them. While stationed at Fort Sumter in the summer of 1863, William Grimball devoted most of a letter to his sister on preparations for the execution for a soldier accused of attempting to desert to the Union Navy, stationed offshore:

The prisoner was brought in a procession, consisting of 1st the provost Marshall, Col. Peter Gailland, then the band playing a dead march, next the prisoner and Bishop Lynch, then the coffin, borne by four men, then the file of men to shoot him, one half with their muskets loaded with ball, the other half with blank cartridges so that no one might know who shot him[.] When the procession arrived at the Square, we commenced on the right and marched along the sides round the Square to the left. The band of the procession playing the dead march until it reached the left of the 1st regiment when it stopped and the band of that regiment took up the dirge and so it continued of each regiment playing and the prisoner arrived in front of them.

Accounts suggest that, even late in the war, soldiers acknowledged a qualitative difference between witnessing death on a battlefield and watching an execution. A North Carolinian suggested that witnessing one “is a much more shocking scene than a battle for in Battle the blood is up & men excited and as no one expects to be hit positively He feels a hope.” He went on to say, “But in these military executions, the blood is cool & the doom of the victim certain & it freezes the blood to witness it.” Watching a carefully choreographed death clearly not only “freezes the blood” but focuses attention in such a way that allows for mentally replaying the affair when it comes time to create a written account.

A condemned man generally spent his final moments fastened to a post, being counseled by a religious adviser and in close proximity to his own coffin. Next came the positioning of the firing squad, and then final orders. William Grimball recalled that once the procession halted, “the prisoner was carried to the post and some minutes were spent in religious exercise” before a “cartridge bag was drawn over his head.” There was generally heightened interest in how the condemned man behaved during those final moments. Facing imminent death provided a moral challenge for the soon-to-be-deceased; by some observers it was seen as a way in which a miscreant might possibly begin to balance out his transgressions, and could represent his first step toward achieving eternal peace.

Arthur Ford recalled that one condemned man “jerked open his shirt and bared his breast to the bullets” as the final commands were issued. “They met their fate without a sigh, without a murmur,” asserted another onlooker. Unlike on the chaotic battlefield, where troops could get through harrowing experiences fueled by an adrenaline rush, witnessing a staged execution allowed soldiers time to speculate on how they might conduct themselves in the same situation.

Executions were not simply designed to carry out punishments and maintain unit cohesion; they provided troops an opportunity to think about the kind of death they wanted for themselves. The pressing question was whether one wanted to die well—facing the end “like a man”—or was willing to be seen as having ended his life in shame and ignominy. Death in combat might be glorified after the fact, but there was no real way to see execution in a positive light, since such an end shamed not only the condemned man but also his family back home.

As witnesses to these final moments, onlookers played the role of the family in characterizing the condemned man’s moral conduct, which in the Civil War era indicated his worthiness of salvation. Indeed, one historian concluded that these final moments on earth offered a “glimpse of an unvarying perpetuity.” After one condemned man received permission for friends to sing a hymn during his execution, for example, a Confederate officer recounted that he spent his final moments praying “aloud that he might be received into that better land.” Evaluating the final moments of a man from the 14th Georgia and another from a North Carolina unit, Marion Fitzpatrick was pleased to learn that the Georgian had “expressed a willingness to die and said he had a hope in Christ.” But as for the North Carolinian, Fitzpatrick said, “He was a sorry looking man, and from what I can learn would talk to no one after he was condemned.”

Last words were seen as providing the clearest possible evidence that a condemned man had repented and was ready to meet his maker. Final statements could be counted on as truthful, since witnesses assumed that the victim had no earthly reason to lie and was aware of the consequences of such a lie beyond the material world. The hope of hearing the right words was made all the more desirable in light of the sharp transition that was about to take place. For Charles Quintard, who served as a chaplain for the 1st Tennessee Infantry, preparing a soldier for death and urging him to repent and offer final words was extremely important. One “poor fellow” under Quintard’s guidance urged him to “cut off a lock of his hair and preserved it for his wife.” Shortly thereafter, he stood up and addressed his comrades, declaring: “I am about to die. I hope I am going to a better world.” He also urged everyone looking on to “take warning by my fate.” As it happened, that soldier’s life was spared at the last moment.

As we’ve seen, not every soldier took advantage of the chance to offer a final statement. One Virginian from Page County responded simply, “No, nothing,” when asked whether he had anything to say. After the order to fire was given, he gasped, fell back and cried out, “O what will my poor wife do?”

Some observers attempted to record the emotions they felt as the final orders were carried out. Martin Coiner of the 52nd Virginia described the moment of execution as “one of the greatest sights that I ever want to behold again.” For James Pickens of the 5th Alabama, the orders to fire brought about “an indescribable & mixed sensation of sickness & horror at the sight.” After an October 1864 execution, another Alabamian, Captain John Hall, could only “pray I may never again be called upon to see” another, while Marion Fitzpatrick asserted, “I shall never forget the impression it made on me.”

The physical impact of the bullets also warranted comment from some. Roughly 60 years after the event, W.N. Wood recalled the execution of a comrade as the Army of Northern Virginia made its way into Maryland and Pennsylvania in June 1863. He had paid particular attention to the pattern of bullets—“four of them could have been covered with a half sheet of note paper, and the other two not far off.” Some observers did not shy away from sharing such disturbing details with loved ones back home. Marion Fitzpatrick explained to his wife the final movements of two condemned soldiers following the orders to fire: “He raised himself perpendicular fell forward and turned over on his back and died instantly. He was pierced through with six balls. The other was struck with only one ball. He turned to one side and was some time dying.”

For at least one Mississippi man, the gruesome details of an execution served to reinforce his role as disciplinarian while he was far away from his family. He used the deaths of the two Louisiana Tigers as examples of what happened to soldiers who “would not behave themselves,” describing each step of the ceremony and emphasizing that after the final orders were given, “these bad men that would not obey orders fell over dead.” In closing, he urged his sons to “Be good little boys.”

Even early in the war, some witnesses downplayed the impact of executions, given what they had seen during battle. Charles Thurston believed that he had “become hardened to any sight since we first stood on the plains of Manassas.” He added, “[T]hat day it was a common thing to have your head taken off while conversing with your neighbor.”

Accounts from later in the conflict suggest that soldiers had come to see executions as more commonplace. Some references seem to point to a kind of emotional numbness or perhaps psychological distancing on the part of witnesses. In the wake of the bloodshed at Gettysburg in July 1863, witnessing two executions in the span of 11 days may not have stood out for Samuel Pickens of the 5th Alabama. At the beginning of September, Pickens noted in passing that 10 deserters had been shot, adding almost casually, “some had to be shot several times.”

Although William Casey, who served in a Virginia artillery unit, might not have witnessed any executions by the beginning of 1864, he would have been well aware of the consequences of desertion. That did not stop him from requesting that his brother “try to catch a deserter and send me a certificate from the enrolling officers and I can get a fifteen days furlough on it.” Casey was clearly eager to spend a few weeks with his family—and unconcerned that his ticket home would be paid by a firing squad.

Despite the emotional toll of having to witness executions, evidence suggests that Confederates overwhelmingly supported the practice as a deterrent to desertion. While Arthur Ford, for example, acknowledged that “it seemed a sad thing that a really brave man should be sacrificed,” he was quick to point out that “it is necessary to deter others from playing the role of traitor.” Seeing deserters as traitors allowed Ford to more easily balance his emotions, and to justify executions as necessary to achieve the moral goal of Confederate independence. Captain Robert E. Park, who served with the 12th Alabama, commented that the latest execution was a “sad sight,” but balanced that with an assertion that “his death was necessary as a warning and lesson to his comrades.” Spencer Welch found it “unfortunate that this thing of shooting men for desertion was not begun sooner.” He speculated that “many men will now have to be shot before the trouble [desertion] can be stopped.”

Sympathy for fellow soldiers was rarely in short supply, and most men had little difficulty appreciating the kinds of pressures that might lead a soldier to desert. But that was not seen as negating a soldier’s responsibility to his unit as well as his role in bringing about an independent Confederate nation. Army chaplains reinforced these lessons by emphasizing the sinfulness of desertion and the relationship between carrying out God’s plan and Confederate independence. Shortly after witnessing an execution, Captain Robert Park recalled listening to the corps chaplain, Dr. Leonidas Rosser, “deliver an eloquent lecture to our Christian Association on ‘Patriotism, Benevolence and Religion.’” As part of a revival that swept through Confederate armies in the winter of 1863-64, an estimated 500 members of the 37th Virginia Infantry attended a meeting in which a resolution was passed supporting the use of firing squads for those “worthless” men convicted of desertion.

Reverend John Paris delivered a sermon following what was perhaps the largest mass execution of Confederate deserters during the war. On February 2, 1864, 53 North Carolinians dressed in Union uniforms were captured by Confederate forces from the brigade of Brig. Gen. Robert F. Hoke, which was under the command of Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett. Most of the captives were from the local area. Twenty-two were publicly hanged in Kinston, N.C., shortly after their capture. Reverend Paris then read a sermon in front of the entire brigade to drive home the importance of maintaining strict devotion to the Confederate cause. He compared deserters to Judas Iscariot and Benedict Arnold, suggesting that discontent within the army was caused by meetings where disaffected soldiers “talk more about their ‘rights’ than their duty and loyalty to their country” and by those who claimed “we are whipt!” “it is useless to fight any longer!” or “this is the rich man’s war and the poor man’s fight!” He also castigated clergymen who preached defeatist messages, and noted that newspapers and letters from home pushed some soldiers over the edge, so that “the young man of promise and of hope once, now becomes a deserter.”

The spiritual glue that chaplains offered as an incentive to soldiers to stay in the ranks doubtless competed with emotional appeals from their families back home. The pleas for help from loved ones only grew louder as the war dragged on, with no end in sight. For some hard-line clergymen like Paris, executions allowed the army to rid itself of those who had become corrupted by others and had lost sight of the goal of independence.

It is almost impossible to gauge the reaction of civilians to military executions, but numerous newspapers included accounts of firing squads, some of them quite graphic. Confederate Captain J.R. Rhodes’ execution in September 1863 was covered by both the Richmond Examiner and the Augusta Daily Chronicle & Sentinel. The primary goal of such accounts seems to have been to deter civilians from tempting soldiers to desert. The Chronicle editorialized: “What a sad warning to the living! Will any profit by it?” It went on to answer its own question, saying, “Some may; others will not.”

Wartime editorials also provide insight into how the public viewed executions. After an 1862 execution, the Richmond Daily Dispatch urged its readers to see desertion as a “crime” and executions as the only remedy, “unless we have determined to abandon the cause altogether.” Many readers surely sympathized with soldiers deserting for the sake of family, but the author reminded them that “All have been called to the service of the country at enormous sacrifice,” and that “What would be an excuse for one man would be an excuse for all.”

A military execution was even the subject of a play in Atlanta in 1862. The playwright, known to posterity only as “The Lady of Atlanta,” conceived her play as an appeal to fellow citizens not to take economic advantage of families with loved ones in the army. The Soldier’s Wife tells the heart-wrenching story of the Lee family. Act One opens with Mr. Lee about to leave for the army, encouraged by his wife. But when Mrs. Lee finds it difficult to find work due to illness and a lack of jobs, a local official in charge of financial relief, Mr. Thompson, refuses to help her, pocketing the money for himself. Meanwhile, on guard duty at the front, Mr. Lee has not received a letter from his wife for months, and fears that she is either dead or too impoverished to afford postage. He resolves to desert and return home. But before he arrives his family is evicted and ends up wandering through snow-covered woods, where they all die of exposure. Lee discovers them, then is arrested for desertion.

The final act of this tear-jerker begins with Lee in prison, waiting to be hanged for desertion, where he learns that members of the community have taken his example to heart, vowing never again to neglect a family in need. Even the hard-hearted Mr. Thompson swears to not betray members of his own community in times of trouble. An epilogue, in the form of a poem, begs the audience to reach out to the families of those who are fighting for their country.

From a modern perspective, The Soldier’s Wife is remarkable not simply for its overt message but also for what it does not address. Not once does a character question whether Lee should be executed for deserting out of concern for his family. Instead he is portrayed as a tragic figure whose death was unnecessary but for the selfish behavior of others. The play’s moral outlook places the individual and the community within a broader context of responsibility for families who were struggling to survive due to the absence of loved ones in the military. Within that framework, desertions and executions were seen as preventable through the aid of others—but punishment for desertion remained a morally justified necessity nevertheless.

The way in which Confederates justified the practice of military executions suggests that they acknowledged the importance of sacrifice—not simply for the sake of maintaining unit cohesion, but as a means of achieving the ultimate goal of independence. Even as late as 1864, when the war had taken a tremendous toll on Southern confidence, Confederates struggled to balance the pain of witnessing comrades shot by firing squads with the belief that it was necessary. Seeing their unfortunate comrades as traitors no doubt helped them to justify that course.

Regardless of the emotional difficulty involved in watching their comrades executed, Southerners overwhelmingly supported military executions as a deterrent for deserters. This is all the more interesting considering that many witnesses found it easy to sympathize with deserters—especially those who were motivated by concern for loved ones at home. The evidence suggests that identification with and sacrifice on behalf of the military and perhaps the nation as a whole was paramount. That Southerners in the army and on the home front were willing to accept executions also sheds light on the extent to which Confederates were willing to go to achieve independence.