Little did Lieutenant Milton H. Ashkins and Sergeant Raymond A. Roberts know when they took off from Ladd Field, Alaska, on June 16, 1941, that decades later the Douglas O-38F they were flying would become an important piece of history at what is now the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force (NMUSAF). The story of how the O-38 arrived at the museum is recalled in a letter from retired Brigadier General Ashkins to a colleague in 1968. Ashkins wrote, “My intent on that flight was to check on the welfare of an old prospector and friend to us all.” He added that after locating the miner from the air, “I came in on a low, slow pass (reduced throttle) to satisfy myself that the old gent was in fact alive and active.” After being assured that the fellow was indeed OK, Ashkins said, “I advanced the throttle and therein was the moment of truth—the tired old engine just coughed and quit.”

A few paragraphs earlier in the correspondence, the general indicated that because of sporadic maintenance, he believed the Pratt & Whitney R-1690 engine’s output had decreased from a maximum of 2,300 rpm to about 1,700, keeping the O-38 just above the cruising speed of 128 mph.

With the engine dead, Ashkins said he guided his biplane into a landing “as slowly as possible into the tree tops.” In fact, he recalled, “Our landing was very soft thanks to the shallow rooted fir trees.” It was 2:50 in the afternoon when the prospector they had come to check on looked up and saw the biplane settle into the trees.

After crawling unhurt from the wreck, the two airmen managed to string an antenna from the experimental Lear radio they had been carrying and called the Fairbanks civilian control tower. (At the time, the Ladd Field tower was not yet complete or operational.) The Fairbanks tower operator passed on Ashkins’ crash message to the military, and within a few hours a Douglas B-18 “Bolo” bomber was dispatched to drop survival gear, including Ashkins’ rifle, a two-man raft and several days of rations.

With the help of the old-timer, Lieutenant Ashkins and Sergeant Roberts spent their first days in the open country, fishing and hunting “and just plain loafing with our prospector friend.” He added that “it took 10 wonderful days to arrive at the pickup point on a highway that was located about 20 miles outside of town.” Both men returned to duty at Ladd Field and were eventually reassigned to separate locations. The O-38 was left in the wooded area near a hillside. It had been judged a total loss, and no effort was made to recover the airframe at the time.

The O-38F Ashkins was flying is believed to be the first military aircraft assigned to service in the Territory of Alaska. Army Air Corps pilots at Ladd Field flew the biplane as a “proficiency aircraft” while the base was under construction in 1941.

The Douglas O-38 series was one of the best-known observation aircraft built for the Army Air Corps between 1931 and 1934. A total of 156 O-38s were built, of which eight were “F” models. The aircraft had a wingspan of 40 feet and a length of 32 feet. Maximum takeoff weight was just over 5,400 pounds. Earlier models of the series carried two .30-caliber machine guns, one fixed forward and one in a flexible mount in the rear cockpit. None of the “F” models were armed.

The plane’s 9-cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-1690 Hornet engine was rated at 625 hp, which gave the aircraft a maximum speed of 152 mph. The O-38 cruised at 128 mph, had a range of 700 miles and a ceiling of 19,750 feet. The cost of one aircraft in the 1930s was $12,000.

The NMUSAF’s aircraft, serial no. 33-324, was manufactured under license by the Curtiss Aircraft Co. in Buffalo, N.Y., and was turned over to the U.S. Army Air Corps on May 16, 1933. After delivery, it was flown to Bolling Field in the District of Columbia. In October 1933, the aircraft was piloted to an assignment at Wright Field, Ohio. Between July 1934 and November 1936, No. 33-324 was assigned to Offutt Field, near Omaha, Neb., back to Bolling and then back to Offutt. It remained at Offutt until September 1938, when it was flown to the Fairfield Air Depot in Ohio.

In June 1939, the plane was transferred to the Middletown Air Depot in Pennsylvania. Less than a year later, in March 1940, the O-38 was taken to the West Coast and assigned to the Sacramento Air Depot. A month later, the aircraft went north to Alaska and the Air Corps Detachment at Ladd Field.

In March 1942, just short of a year after the crash, with 2,285.8 flying hours, the airframe was dropped from the military’s inventory. For almost 30 years it lay in the Alaskan wilderness. Over the years, the crash site was generally known to civilian and military aviators who traversed the area around Fairbanks and Eielson Air Force Base. The biplane’s remains were visible from the air, but no one seemed interested in it until 1967, when word of the vintage wreck filtered back to officials at the U.S. Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

In the fall of that year, Captain Robert Peterson, flying a Piasecki (Boeing-Vertol) H-21 Shawnee helicopter, landed at the crash site and took a closer look at what was left of the O-38. What he found was described in subsequent reports as “a recoverable aircraft” that showed little signs of deterioration. Peterson reported that the cloth coverings were “torn and shredded, and it [the airframe] had suffered some structural damage in the crash landing.” But he also pointed out that the mechanic’s tools that had lain for nearly three decades in some of the world’s coldest weather “showed barely a sign of rust.”

The pilot’s handbook, which was not even yellowed from age, was recovered in good condition as well and bore the penciled notation: “Cracked up June 16, 1941, 2:50 p.m. No injuries to self or mechanic—Lt. Milton Ashkins.”

In April 1968, Captain Peterson, along with Charles Gebhardt, who had formerly served as chief of the Aircraft Restoration Division at the U.S. Air Force Museum, returned to the crash site. Gebhardt’s inspection determined that the remains of the O-38 could be salvaged and restored.

At the time, Gebhardt called the 1930s vintage aircraft “a rare find” of considerable importance to the museum, because it had “very little representation from this period.” He added that this was the first observation plane of the period that had become available to restorers.

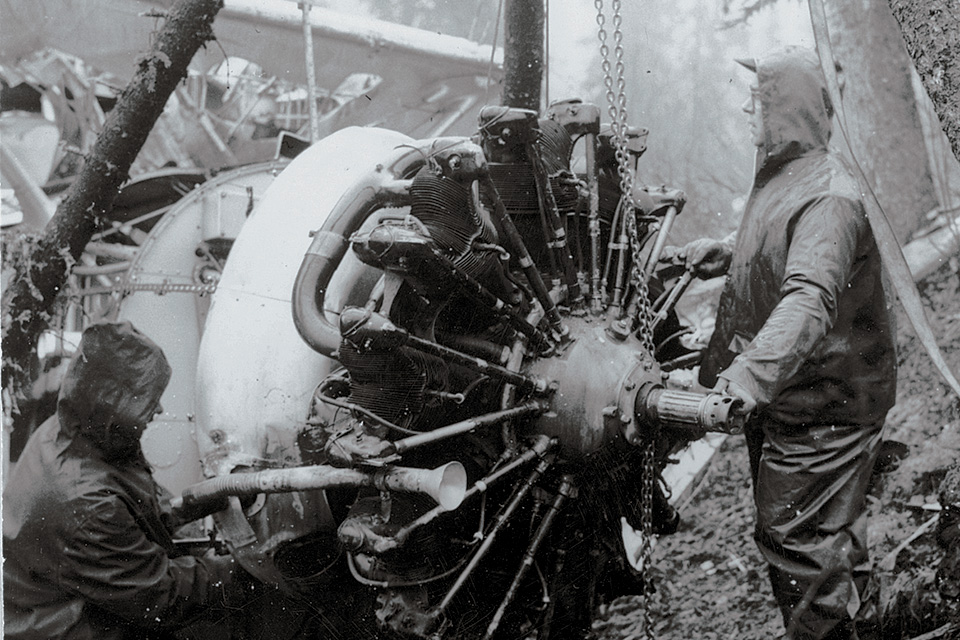

During the next two months, Peterson and Gebhardt devised a plan for the O-38’s recovery. On June 3, 1968, a crew of military specialists moved into the area, set up a camp and began the task of disassembling the aircraft in the wilderness. Extracting the O-38 from the backwoods of Alaska proved to be a daunting task. First, a number of trees had to be cut to reach the airframe. Then a path to a clearing had to be created to position the wreck for recovery by the helicopter. The engine mounts, which had been twisted in the crash, made removing the Pratt & Whitney Hornet extremely difficult and time consuming.

After several days of backbreaking work on the part of the ground crew, an Army Boeing-Vertol CH-47 Chinook arrived from Fort Greely, Alaska. The O-38’s engine, which weighed between 840 and 1,070 pounds, was freed from the fuselage and loaded inside the heavy-lift helicopter. The upper and lower starboard wings were detached and strapped to the sides of the fuselage. (These wing sections would later serve as patterns for new wings that would be constructed at the museum.) This bundle of recovered parts was then loaded into a sling, lifted into the air beneath the Chinook and hauled back to Eielson Air Force Base. The port wings were determined to be too badly damaged to salvage and were left at the site.

A Lockheed C-130 transported the disassembled biplane to Wright-Patterson on August 7, 1968, where it was placed at the museum’s restoration facility. After further disassembly, all parts were cleaned and inspected. Thanks to Lieutenant Ashkins’ “soft landing” in the trees, the landing gear did not suffer serious damage but had been pushed back into the fuselage underside. Museum craftsmen were able to repair some of the existing parts, while other parts had to be fabricated from aluminum sheet and stock.

The engine compartment was in the worst condition. The mounting assembly was badly twisted and had to be re-manufactured. This required the acquisition of special steel tubing that had to be cold-rolled into the proper shape and diameter. Custom dies produced in the metal shop were used to press complicated shapes into the steel ring that would eventually accept the engine mounting tabs.

The main section of the fuselage suffered little from the crash. The fuel and oil tanks were removed, cleaned and repainted. Amazingly enough, after nearly three decades in the Alaskan weather, the tanks were not corroded and passed pressure tests with no leaks.

The engine cooling shutters were cleaned, straightened and repaired, as was the inner cowling. Pieces of the aluminum fuselage that had been damaged in the mishap were straightened, repaired or replaced. The cockpit areas were so well preserved that the instrument panels, flooring and rudder pedals needed only a good scrubbing to return them to their original appearance. Even the engine primer hand pump was found to be functional after cleaning.

All the tail surfaces were in fairly good condition, with only the fabric on the horizontal stabilizer and rudder needing replacement. The fabric on the vertical stabilizer proved to be in excellent condition and still bore the manufacture date of “4-22-31.” This material was left as was.

The tail wheel, one of the seats and two sections of the canopy had been damaged by a brush fire while the plane lay in the woods. Enough of the tail wheel remained to serve as a pattern for making new parts, however. The lip of the seat that had been burned was removed and replaced. The broken sections of the canopy were replaced with new glass.

Other than the engine compartment, the most serious damage sustained by the O-38 was to the wings. Restorers in the wood shop obtained original wing rib and wing panel drawings from the Douglas Aircraft Company. With these in hand, they went to work, cutting spruce spars and ribs, and then forming them into shape and gluing them together. The new wings were covered with mercerized cotton and brushed with several coats of dope to draw the fabric tight over the ribs.

On Armed Forces Day weekend in 1970, the partially restored O-38 went on display at the museum along with a slide show that detailed the recovery process in the Alaskan interior. It was estimated that more than 50,000 people viewed the exhibit.

By 1974, the O-38 restoration was nearing its finish. To complete the project, the aircraft was painted with several coats of silver lacquer. Since the O-38 was being restored to the period when it served in snow-covered regions, the cowling, top of the upper wing, the vertical stabilizer and a fuselage band near the tail all received a coat of high-visibility orange paint.

After returning to Ladd Field following the crash of the observation plane, Lieutenant Ashkins continued his military service. During World War II he flew 59 combat missions, shooting down one enemy aircraft and reporting one probable victory. In 1965 Ashkins retired to Southern California with the rank of brigadier general, concluding a career that spanned 27 years.

Recalling his experiences after the crash of the O-38 in Alaska, the general wrote in later years, “It was the most enjoyable field trip I’ve ever been on.”

This feature originally appeared in the July 2006 issue of Aviation History. Don’t miss an issue, subscribe today!