AFTER HE SURRENDERED the demoralized remains of the Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant on April 9, 1865, Robert E. Lee stayed at Appomattox until the last of his troops had given up their arms and been paroled on April 12. Even then, Lee did not race the hundred miles home to Richmond. Along the way he spent one final evening at the camp of his top commander, Lieutenant General James Longstreet, and another night at his brother’s farm, where out of habit or solidarity with his dispersing army he slept outside in his tent. As he went he took in the war’s destruction, from burned-out farmhouses to downed bridges to animal carcasses in the road. His army had destroyed the two bridges over the James River into Richmond, so when Lee finally reached the former capital of the Confederacy on the afternoon of April 15, he crossed a pontoon bridge put up by his recent enemy.

With him were two of his three sons, some aides, black servants, and a seriously wounded Confederate officer. Two wagons accompanied this party, one of which bore an old quilt as a makeshift cover where the canvas had worn away. It had rained that morning, and both Lee and his beloved horse, Traveller, were spattered with mud. They first passed through the part of Richmond that burned when the Confederates had fled, the streets bisecting piles of charred rubble. When they reached beyond the fire line, word spread that Lee was back, and the people came out to greet him. As Douglas Southall Freeman puts it in his biography, “Along a ride of less than a mile to the residence at 707 East Franklin Street the crowd grew thicker with each block. Cheers broke out, in which the Federals joined heartily.” Lee acknowledged these displays of affection and respect by doffing his muddy hat. When he arrived at the rented brick house where Mrs. Lee was living, he had trouble getting down from Traveller, overcome either by the emotion of the moment or the weariness of the years of war. One woman who looked on felt that his body simply would not do what he asked of it. Once dismounted, Lee struggled through the well-wishers who surrounded him, shaking hands, and then entered the house and his new life as a civilian.

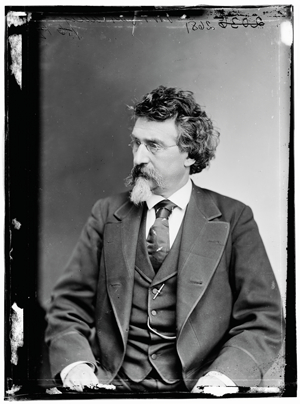

THE PHOTOGRAPHER MATHEW BRADY had been in Richmond for several days, making nearly 60 photographs of the ruined city. He got wind of Lee’s return and asked an old acquaintance, Confederate colonel Robert Ould, to appeal to the general to have his photograph taken. Ould, who had been a district attorney in Washington before the war and become the chief Confederate officer in charge of prisoner exchange, had been given something like diplomatic immunity by Grant. Brady said in a newspaper interview late in life that both Ould and Mrs. Lee had helped him persuade the general to submit to the camera, although as Brady put it, “It was supposed that after his defeat it would be preposterous to ask him to sit.” But, Brady continued, “I thought that to be the time for the historical picture.”

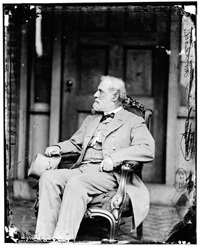

Apparently Lee, or perhaps Mrs. Lee, agreed, because it was arranged that Brady could come to the house and make his pictures. The next day, Easter Sunday, Brady took six photographs in all: four of Lee alone and two of him with his aide, Colonel Walter Taylor, and his oldest son, Major General Custis Lee, who had been captured only three days before the surrender. Brady posed the officers beneath the overhang of the back porch, on the basement level, because the light was best there.

LEE’S YOUNGEST SON, ROB, would write years later of his father: “I believe there were none of the little things in life so irksome to him as having his picture taken in any way.” But Lee had a fine sense of history, for instance wearing for his surrender his best uniform and a dark red silk sash—Grant says in his memoirs that “General Lee was dressed in a full uniform which was entirely new, and was wearing a sword of considerable value.” However much Lee disliked posing, on this Sunday morning he once again put on a clean uniform and wore well-shined black shoes, but he left aside the sash and the sword and the boots. Charles Bracelen Flood in his book Lee: The Last Years points out that this uniform also had “no braid on the sleeves.” Lee was acutely aware of his power to set an example for the South and had urged his former troops to swallow their anger and return home to rebuild their lives. Grant wrote in his memoirs that at Appomattox he had “suggested to General Lee that there was not a man in the Confederacy whose influence with the soldiery and the whole people was as great as his.” In the wake of Lincoln’s death the day before, and the charges that the South was responsible, Lee might also have chosen to pose in the domestic setting of his home—a leader still in his uniform, but sans sash, braid, sword, and boots, visibly morphing into a civilian—as a symbol of stability and responsibility in very dangerous and uncertain hours.

Lee was already a beloved figure, and not only in the South, as those applauding Union soldiers on the streets of Richmond attest. “The people of Virginia and of the entire South were continually giving evidence of their intense love for General Lee,” Rob Lee wrote. “From all nations, even from the Northern States, came to him marks of admiration and respect.” But these photographs—in which the physically and morally exhausted general, grizzled at age 58, summons the strength of his unusual personal dignity for Brady’s camera, showing no trace of the humiliation of defeat but only a self-possessed seriousness—gave the South a hero to cling to in those dark days after the war, and for decades to come. One photograph in particular became iconic. In it, the hatless general’s head is squarely centered in front of the crossed rails of a panel door, suggesting Christ on the cross to those for whom Lee would become a powerful symbol of the martyred South.

Brady’s images of Lee were widely distributed—Brady said later he sold them by the thousands—and even Mrs. Lee kept a store on hand for the many people who asked her for signed photographs of her husband. Rob Lee quotes a November 1865 letter from his father, then living in Lexington, Virginia, where he had taken up the presidency of Washington College, to his mother, who had not yet joined him there, saying that he had dutifully signed and returned a batch of photographs she had sent to him. In his years as president of the college he would sign thousands of card photographs for students to raise money for their organizations.

Who but Brady could have pulled off this photographic and journalistic coup? He said he had known Lee “since the Mexican war when [Lee] was upon Gen. Scott’s staff,” so “my request was not as from an intruder.” Brady had also quite likely met Lee in the 1850s, when the future general spent three years as superintendent of West Point. And Brady or his studio had taken portraits of every American general who had mattered at all, including many who had served with Lee in the U.S. Army before the Civil War. Finally there was Brady’s own reputation as a portraitist, upon which Lee could rely. The general chose well, because these images match their subject for dignity and seriousness, for a rich sense of the suffering Lee had overcome to place himself before the camera, and for a firm eye on the historical importance of what showed upside down as Brady or his operator peered through the lens in his last act as a wartime photographer.

Robert Wilson is the editor of The American Scholar. This story is adapted from his new book, Mathew Brady: Portraits of a Nation (Bloomsbury).