Staff Sgt. Jerry Auxier had been missing in action since a bomb explosion in July 1968

Midway between Hawaii and Japan on a flight across the Pacific Ocean, my thoughts as I drifted into sleep turned from the present, March 2, 2017, to the past and then to the present again. How did I get here? What was I doing on a plane to Vietnam? I remembered, of course. I was going back to July 29, 1968, when I was a rifleman with Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 46th Infantry Regiment, 198th Infantry Brigade, 23rd Infantry Division (Americal).

Midmorning that day we were hanging around the helicopter pad at Landing Zone Young in the northern part of South Vietnam, waiting for choppers. Helicopters carrying 1st Battalion’s Alpha Company would land so Alpha could replace Charlie Company on bunker guard duty at LZ Young. We would then board the chopper and replace Alpha tromping through the jungle in search for the enemy. We were airlifted to Que Son Valley, about 10 miles away.

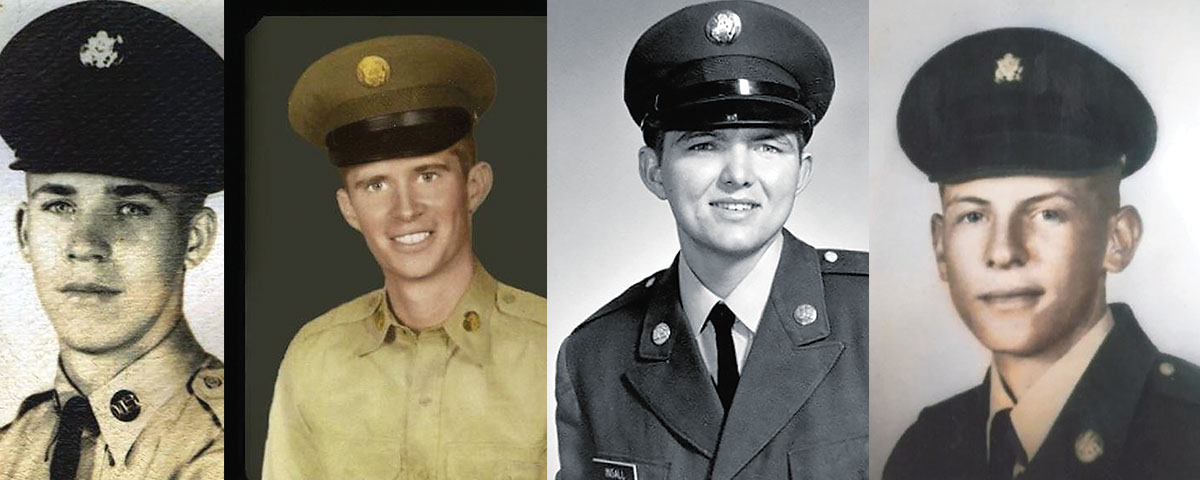

On the first day in the field, as we were setting up camp for the night on a hill, another chopper came in. Just before it landed, I heard a powerful explosion and saw the aircraft lying on its side. Earlier the Viet Cong had found an unexploded 500-pound American bomb and rigged it for remote detonation to bring down the chopper. The crewmen were beaten up but survived. The explosion, however, killed three members of Charlie Company who were on the ground—Spc. 6 Luther Sexton, Cpl. Donald Greene and Spc. 4 Billy Insall. Ten were wounded, and Staff Sgt. Jerry Auxier was missing in action.

Forty-nine years later, I was returning to Vietnam to meet a team from the Defense Department agency that tries to find and identify the remains of missing service members from all wars. We were going to Que Son to search for Auxier’s remains.

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency’s lead investigator for the mission, Ray Kern, met us at Da Nang International Airport and then we checked into a local hotel. At an early breakfast the next morning, Kern briefed me on the plan for the next several days, making me feel right at home and part of the overall project. An Army retiree with 12 years at DPAA, Kern had a plethora of information on how things worked, not only in Vietnam but in all of Southeast Asia.

Although I wanted to go right into the field and get to work, Kern explained that that the agency’s 10-man research investigation team was finishing its work at another site and wouldn’t be back in Da Nang for a couple of days. Basically he told me to relax, enjoy the sights and acclimate myself to the weather—sound advice for a man my age.

As promised, the team arrived in Da Nang on schedule. It was led by Sgt. 1st Class Marcus Taylor, an Army Ranger with 11 years in the military and seven deployments to Afghanistan and Iraq. When Taylor spoke, the team paid attention.

Each member came with his own distinct talents.

Sgt. 1st Class Christopher Varner, an 11-year Army veteran with multiple deployments to Afghanistan and Iraq, was the assistant team leader and a lead investigator. He had been with DPAA for almost a year. His natural leadership skills instilled pride and confidence in the entire team.

Sgt. 1st Class Kelvin Ngo and retired Navy man Khuong Vu, both born in Vietnam and now American citizens, were the team’s two linguists. Ngo, a veteran of the Iraq War, had been with DPAA for four years. Vu had worked there for 16 years. Without their expert language skills and knowledge of the local Vietnamese culture, the team’s efforts would have suffered greatly.

Any medical misfortunes were addressed by Petty Officer 1st Class Dennis Anderson, a hospital corpsman, and Army Col. John Vogel, who were always close by.

Dr. Joshua Peck, an anthropologist, and Dr. James Cloninger, a historian and archivist, were the “brains” of the team. They have years of experience throughout Southeast Asia and were the go-to guys whenever the team had questions related to history, anthropology or archeology.

Rex Hodges, an expert on all aircraft parts that have anything to do with sustaining the life of the pilot and crew, was the team’s “life support technician.” A small, innocuous-looking piece of metal or a seemingly unidentifiable bolt or clamp would be a mystery in the hands of a layman, but not in Hodges’ hands. He can immediately identify the part and tell you what type of aircraft it came from. Hodges, an Air Force veteran with DPAA for 17 years, has worked in Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Papua New Guinea and a few other countries he can’t mention.

Staff Sgt. Stephen Alvarez was the team’s “explosives ordnance disposal” guy. The nine-year Air Force veteran, who did tours in Afghanistan and Iraq, made sure the search site was clear of any explosive devices before our work began. He has an uncanny ability to detect small fragments of metal beneath the earth, a skill that helped the team again and again.

When we were ready to go into the field, all of us put our gear and personal belongings into the truck and headed south to the city of Tam Ky, where we would be spending the night before our trip into Que Son Valley. We rode in a convoy of four SUVs driven by local officials. Local regulations restricted us from driving the vehicles ourselves. In Tam Ky, we checked into a hotel near the city’s railroad station. Shortly afterward, our work began.

I sat down with Ngo, Vu, Cloninger and team leader Taylor in a private section of the hotel to go over the game plan for the following day. I also discussed my memories of that tragic event so many years ago. We sat there for several hours, scrutinizing maps, aerial photos, after-action reports, company and battalion logs, personal letters recounting memories of the explosion and anything else we thought might help our efforts the next morning. We worked hard on the details to be sure we searched the exact site where the helicopter went down. Being off a just a few feet could be the difference between success and failure. We concentrated on the hill, my position there and what happened that day in July 1968.

Spc. 6 Luther Sexton. (Soldiers: Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund)

I struggled to remember every little detail and present a concise version of my testimony. I realized it was crucial to rip apart and examine every detail, but pulling out those memories was an emotional roller coaster ride.

In the morning we piled into our vehicles and headed west into the mountains of the Que Son Valley. With us was a Vietnamese colonel in civilian clothes. My team told me that all MIA missions had to have a Vietnamese presence, including drivers, interpreters and laborers.

The drive was almost two hours long, starting on highly congested streets and ending on deeply rutted dirt roads. At the base of the hill we were met by members of the local government and workers who would help clear the area. We climbed the hill in a column formation with little difficulty. It was still only midmorning, but the temperature and humidity were already high. Anderson, our hospital corpsman, stayed close and kept reminding me to drink water. Indeed, every member of the team remained solicitous of my health throughout the day. “You OK, Mr. Cunningham?” “You need anything, sir?” “Are you drinking water, Mr. Cunningham?” were common inquiries during the entire day.

I constantly scanned the area as I climbed, and once I reached the top of the hill, Vu told me to walk around and try to familiarize myself with the surroundings. Meanwhile, he and the other investigators interviewed local residents and officials. The investigators were going to compare my thoughts, comments and recollections with others to see if our stories matched to help determine if this was indeed the hill of July 29, 1968.

I slowly walked around the top of the hill, gradually expanding my circle. I immediately saw the crater caused by the bomb explosion. I saw numerous foxholes on top of the hill, imagining these were dug by members of our command post. As I expanded my circle, I came upon holes along the perimeter. They were overgrown with vegetation and had partially collapsed over the last 49 years, but they were foxholes—all manned by my company, Charlie Company. About this time, I broke down. I collapsed and began weeping. I was totally overwhelmed by being back on this hill where so many suffered, so many years ago. My body trembled. I felt a comforting presence of others—the team members or someone else? I couldn’t tell. Reflecting on that moment, I was probably overwhelmed with the memories—but maybe not!

As I was sitting there, Vu interrupted my thoughts. I looked up, and he was smiling from ear to ear. After interviewing all the local witnesses—even members of the militia who were responsible for detonating the bomb—he was certain we were on the right hill. Vu told me the witness statements were virtually identical. I am sure he was relieved knowing we were on the right hill. I didn’t need reassurance from anyone. I felt it in my mind, in my soul, in every fiber of my body. I had returned.

Now that we knew we were at the site of the 1968 explosion, it was time to survey the area to collect physical evidence documenting our claim. Before we got started, we took a quick break for lunch, which consisted of a small Vietnamese bread roll (banh mi) stuffed with mostly lettuce and some kind of meat, followed by more water.

Just before the lunch break, villagers started to arrive at the top of the hill. I first saw a man and a little girl that I assumed to be his daughter. Then a woman showed up with her husband and son. Next an older man appeared with a couple of more kids. These were the cutest, most curious, children I had ever seen. Well-behaved, they just stared at us, wondering what we were doing. I realized this was probably the most entertainment they had had in a long time. Having many grandchildren myself, I was smitten by these little kids. I approached them with a big smile on my face and tried to talk with them in Vietnamese. They just stared at me. I think that after many attempts my butchered Vietnamese began to make at least a little sense to them because they started to relax and smile.

Eventually the children began to roam the hill, taking in everything we were doing. It was such a pleasure watching these kids enjoying themselves. After all, weren’t they part of the reason we went to Vietnam in the first place? I reached into my pockets and pulled out a fistful of Vietnamese money and distributed it to the kids. Luckily, I had quite a lot of 20,000 dong bills (20,000 dongs equal about $1 American). The kids were most appreciative, and every time they received a bill, they held their hands together and bowed. I noticed other members of the team were reaching into their rucksacks and giving out treats—candy bars, crackers, water. Those kids made some of America’s toughest fighters into a bunch of pussycats. I was proud of our veterans for being so kind and compassionate. The presence of those little kids on the hill brightened our day.

Another experience at the hilltop was spine-tingling. I met the two men responsible for placing and exploding the bomb that killed and wounded so many of my friends from Charlie Company. They were in the group of Vietnamese eyewitnesses that our linguists interviewed earlier that morning. When we met, emotions flowed. We had tried to kill each other 49 years ago; now we were shaking hands, smiling and hugging each other. I gave the man who actually exploded the bomb a hat from the 198th Light Infantry Brigade. He proudly took off his hat and put on the hat I had given him. We all smiled together and took pictures. Divine intervention was working overtime on that hill that day.

Following our break, the team, led by anthropologist Peck, began to survey the hill. Although the process is more complicated than I can comprehend, I will give you the layman’s version of how to survey a site. First, Peck laid out a roughly 50-foot tape measure north and south and then east and west. Once that was done, Alvarez, the explosives-disposal guy, began sweeping the hill with his metal detector using the tape as a guide. Every time Alvarez’s detector indicated a metal object, a team member stuck into the ground a small rod with a colored flag.

After the entire top of the hill was swept by the metal detector and the hits identified with flags, all of the team members grabbed a trowel, dropped to their knees and began digging. What we found was amazing. We verified with physical material the evidence of an explosion and a helicopter crash.

We unearthed and collected bomb fragments, pieces of the helicopter skin, a turbine blade from the engine, honeycombing from the main blade, M16 rifle and M60 machine gun rounds (spent and unspent). The mood of the entire team seemed to be uplifted. So many times a DPAA team will go to a site and find nothing. This time the team found everything. Except Auxier’s remains.

The afternoon was fast disappearing, and the day’s work was coming to an end. Hodges walked the entire area, documenting the site with countless pictures. All the flags had been collected and stowed in Peck’s backpack. We were ready to leave the hill, but there was one other thing I wanted to do.

I wanted a team picture with all of us holding an American flag I had packed in my rucksack. I asked Ngo if this was possible, and he shook his head in the negative. The Vietnamese colonel accompanying us would never allow it; he had never in the past, and Ngo knew he wouldn’t today. Even so, I asked Ngo if he would seek the colonel’s permission. He reluctantly said he would.

As I stood there waiting for Ngo to return, I reflected on the day’s activities. After 49 years, I had returned to this hill and successfully re-created the events of that tragic day so long ago. In my mind, this was a miracle. All of us on the team could all be proud of ourselves for never giving up. Our country, unlike many other countries, still searches for its POW/MIAs— something else to be proud of and reassuring to all our troops in the field.

Ngo returned shortly with an incredulous look on his face. The colonel gave us permission to take a team picture holding the American flag. In fact, he insisted in being in the picture! I immediately dug the flag out of my rucksack, and the team gathered together for the picture. We were a bunch of proud and thankful Americans, knowing we did all we could do to bring all our troops home, back to their loved ones.

As we slowly walked off the hill, following the same path we had come up earlier in the day, I stopped, stepped off the trail, looked back up the hill, and with tears flowing down my cheeks, gave a final salute to my fallen comrades. God bless them all!

What’s next? That was my question. After a successful investigation, documenting the site and providing substantial physical evidence, we nonetheless did not find Auxier’s remains to return to his family. Wasn’t that the primary purpose of the mission?

Kern addressed my questions in his usual candid, forthright, respectful manner. Yes, we did have positive results, but now we had to follow protocol. Kern and other DPAA officials would present the facts and findings to their superiors, then ask for permission, authority and, most important, the money, to initiate an excavation. We are still waiting for DPAA clearance.

Even if DPAA, with limited financial resources, provides funding for an excavation, we have to receive permission from the Vietnamese government to proceed. We will see what happens, but we are sure of one thing. The research investigation team members did their best to bring Auxier home. They can be proud of themselves for a job well done.

—Vietnam veteran Michael H. Cunningham is a retired U.S. Customs official. He is the author of Walking Point: An Infantryman’s Untold Story.

This article was published in the October 2018 issue of Vietnam.