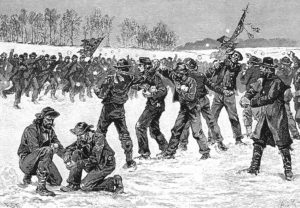

The Army of Northern Virginia went to war with itself in February 1863

Missiles filled the air, and Confederate troops soon began to falter under their blows. Rebel Yells echoed off the hillsides as desperate charges and countercharges swept the fields. But the missiles were made of snow, not deadly iron or lead, and both sides issued the Rebel Yell as Robert E. Lee’s troops fought each other in what was “probably the greatest snowball fight ever fought,” according to a veteran of the battle.

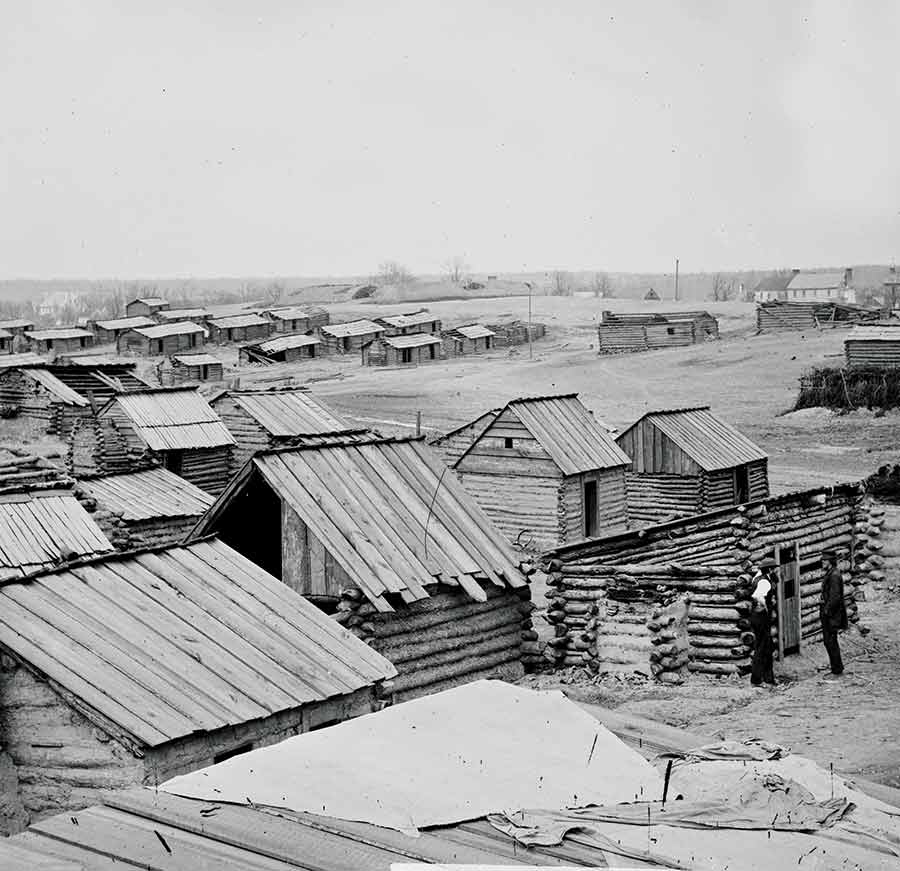

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]inter camp, while often free from actual combat, could still be brutal and boring for Civil War soldiers. Impassable, muddy roads and the constant inclement weather made active military operations impossible. Disease ran rampant, killing more men than battles. Soldiers suffered grievously when confined to close quarters with poor sanitary conditions that lacked the appropriate systems to provide clean water and clear away waste.

Boredom was also an ever-present problem and an insidious enemy. It was mandatory that officers keep their men moving and active during the winter months to try and stave off both psychological and physical maladies. Drilling was surely one form of activity, but the incessantly mundane and repetitive aspects of it numbed body and mind.

Historians have written that the experience of being in battle tended to exaggerate the aggressive aspects of the Southern male culture. Indeed, there was an obvious pride in one’s fighting ability, and the free time, the ongoing desire to prove themselves to one another, the absence of women, and the tension, anxiety, and angst about forthcoming battles, all meant that the soldiers took with them their combative and “fighting spirits” into their leisure time. When possible, the shared experience of team sports in camp helped unify the troops. These activities not only relieved the monotony of camp life, but also engendered a sense of community among the soldiers and gave them a shared purpose.

pair that belonged to a Union soldier, to troops

in winter camp. (Heritage Auctions, Dallas)

Commanding officers and soldiers alike sought to establish regular routines and work schedules to alleviate the boredom. Camp maintenance and upkeep, religious services, letter writing, card games, story-telling, musical, poetic, and dramatic presentations all became an integral part of camp life. Because the winter encampments were in essence solitary villages, complete with crisscrossing streets, there were makeshift churches and sutler shops. And despite the hardships, the winter months allowed the soldiers an opportunity to bond and enjoy their more permanent camps. They were always looking for the opportunity to have a little fun and break the tedium.

On a daily basis, from the first arrival of snow until the melting of the last flakes in the warmth of the spring, soldiers were eager to pelt each other with densely packed snowballs. No one, including officers, was spared. “I knew that I would have to be snow balled at some time,” recounted South Carolina Colonel C. Irvine Walker, “for the men did not let off any one in the brigade….So I thought it would be best to go down and take part in the fight and be snow balled….The men made however a regular Pandean frolic of it. All distinctions were levelled and the higher the officer the more snow balling he received.”

“As if unable to satisfy his martial urges by fighting Yankees with guns and sabers in regular season,” the eminent historian Bell Wiley wrote, “Johnny Reb now armed himself with snowballs, formed regiments and brigades from his own ranks, dubbed opposing comrades ‘the enemy,’ raised a yell, and charged with a realism that quickened the pulse of participants and spectators.” “Prisoners of war” were also captured in the sham battles, and sent to the rear to be paroled or exchanged in POW swaps. Once the bombardments began and battle formations were drawn, officers rode the lines exhorting their troops and barking out orders. The mounted figures made conspicuous targets and the men eagerly besieged them with snow. Soon the long-range artillery of snowballs yielded to hand-to-hand combat as the soldiers responded with resounding cheers and jeers.

On rare occasions the soldiers’ snowball battles even drew spectators. Visitors from nearby towns and from the neighboring countryside would happen by to observe the maneuvers. In at least one instance, the presence of females turned the tide in battle. “We all commenced snow balling,” a participant in the battle wrote home, “Gen Wright, his wife and daughters & other young ladies came to see the fight. We got whipped but the ladies were the cause [since] the boys all stopped to look at them and the other side fought so our party kept giving back until the others got the general and the girls prisoners.” That group of battle-tested Confederate veterans allowed victory to slip through their fingers due to the attendance of female onlookers.

The winter of 1862-63 in Virginia was quite cold, and the season came in like a lion. On February 22, Jefferson Davis’ clerk and diarist J.B. Jones wrote from the Confederate War Department in Richmond that “it was the ugliest day I ever saw. Snow fell all night and was falling fast all day, with a northwest wind howling furiously. The snow is nearly a foot deep and the weather very cold.” A soldier in the Confederate camps near Fredericksburg awakened to find that “about eight inches of snow had fallen and covered us during the night” and that some of the horses had died from exposure to the frigid conditions. “That winter in Virginia was one of the most severe known in many years,” wrote D. Augustus Dickert of Kershaw’s South Carolina Brigade, “but the soldiers had become accustomed to the cold of the North, and rather liked it otherwise, especially when the snow fell to the depth of twelve to sixteen inches, and remained for two to three weeks.”

All that snow prompted a major snowball fight on February 25 in the Army of Northern Virginia’s camps. In many respects it was a typical Civil War battle with common tactics. Confederate cavalry, infantry, and skirmishers moved quickly and stealthily along the white covered landscape, the dense snow muffling their approach as they sought to overtake their enemy’s camp. But this was a battle not quite like the countless others that occurred during the Civil War. The ammunition on this occasion was snowballs and the entire maneuver could be considered a great case of friendly fire. Some estimates put the number of participants in this great snowball fight at 10,000.

Brigadier General Robert F. Hoke’s North Carolina soldiers launched the attack, moving swiftly toward Colonel W.H. Stiles’ camp of Georgians. Dickert, one of the participants that day, provides the most comprehensive account of the battle. “The fiercest fight and the hardest run of my life,” Dickert wrote, “was when Kershaw’s Brigade under Colonel [William] Rutherford, of the Third challenged and fought Cobb’s Georgian’s….When the South Carolinians were against the Georgians, or the two Georgia brigades against Kershaw’s and the Mississippi brigades, then the blows would fall fast and furious.”

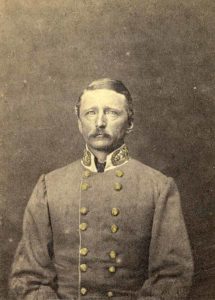

General Joseph Kershaw

commanded six South Carolina

units whose tenacity at winter war

belied their prewar inexperience

with snow. (The American Civil

War Museum)

Colonel Rutherford apparently loved such activities as snowball fights and he enjoyed the sport as much as his men. Dickert observed that Rutherford assembled his men for battle by the beating of drums and the sounding of the bugle. “Officers headed their companies, regiments formed, with flags flying,” recorded Dickert, “then when all was ready the troops marched down the hill, or rather half way down the hill, and formed [a] line of battle, there to await the coming of the Georgians.” As one author has written: “Despite the element of surprise, the attackers were pushed back, as their targeted brigade had been swiftly reinforced by nearby soldiers.”

Ammunition was stockpiled in great pyramids of snow built and organized to the rear of the newly formed battle line as the soldiers awaited the rapidly advancing enemy. The cheering was deafening and gave new meaning to the famed and feared Rebel Yell. Officers beseeched their men to stand fast and defend the honor of their states “while the officers on the other side besought their men to sweep all before them off the field.”

With all the adrenaline and anxiety of battle, Dickert describes his comrades in arms as standing “trembling with cold and emotion, and the officers with fear,” for the penalty of being captured was the fate of being whitewashed with snow. Rufus King Felder of the 5th Texas wrote home to his wife that “the boys had a fine time…fighting battles with snowballs…the storm of battle raged with the utmost fury.…When we got [them] in sight they had the long roll sounded and their officers leading them out in force. We did not succeed in effectually subduing them but held our ground. It is indeed a grand sight to see several thousand men drawn up in line of battle fighting with snow & with as much earnestness as if the fate of our country depended upon the contest….it is more interesting to look at these battles than a real one as there are no lives lost & but little blood shed.”

There were “head on assaults and flanking attacks, authentic generals, and colors, signal corps, fifers and drummers beating the long roll, couriers and cavalry,” wrote one participant, “and showed that ‘men are but children of larger growth….’ If all battles would terminate that way it should be a great improvement over the old slaughtering plan.”

The pandemonium and excitement was vividly described by a Georgia private in a letter home to his family. “Some time the hole brigade forms, and it looks like the sky and the hole elements was made of snow and a hole had broke right through the middle and it is no rare thing to see a Cpt or a Col with his hat nocked off and covered in snow. Gen Longstreet and his agitant took the regs the other day and had a fight with snow balls but the Gen charged him and took them prisners.”

When the Georgians approached, the command was given to fire. “Then shower after shower of the fleecy balls filled the air.” Dickert observed that “cheer after cheer went up from the assaulters and assaulted—now pressed back by the flying balls, then the assault again.” After several minutes of fierce fighting the Georgians broke through the Carolinians’ line. “The fierce looks of a tall, muscular, wild-eyed Georgian, who stood directly in my front,” Dickert wrote, “seemed to have singled me out

for sacrifice.”

Kershaw’s Brigade attempted to hold its ground, but eventually gave way. “I saw the only chance to save myself from the clutches of that wild-eyed Georgian was in continual and rapid flight.” Dickert, “a boy seventeen years old, and never yet tipped the beam at one hundred” recalled that “in the grasp of that monster, as he now began to look at me, gave me the horrors.” The Georgians pressed on and Kershaw’s Brigade came under heavy assault. It became an all-out fight to the finish as the “broad expanse that lay between the men and the camp was one flying surging mass, while the earth, or rather the snow, all around filled with men who had fallen or been overtaken, and now in the last throes of a desperate snow battle.” Having experienced the horrors of real battle, the cathartic enjoyment of fighting a battle where the injuries would be, for the most part, limited to black eyes, skinned heads, sprained ankles, and other minor injuries, completely engulfed the thousands of soldiers frolicking in what had become, for a fleeting few moments, the winter wonderland of Virginia.

“The men who had not fallen in the hands of the reckless Georgians had distanced me, Dickert recalled, “and the only energy that kept me to the race was the hope that some mishap might befall the wild–eyed man in my rear, otherwise I was gone.” Dickert’s Georgian pursuer followed him all the way into his tent, only to confess to Dickert that he “‘would rather have caught that d—n little Captain than to have killed the biggest man in the Yankee Army.’”

So important was this much needed, and even more enjoyed, event in the Rappahannock Valley that apparently it was witnessed by Robert E. Lee, who himself was struck by several snowballs, and by Stonewall Jackson and his staff. Jackson, however, refrained from participating in the merriment. One of Jackson’s senior staff officers remarked that he had very much wished that they had participated in the fight so he could have aimed snowballs at “the old faded uniforms.” With such excitement in winter camp, the Richmond newspapers even covered the battle by devoting several columns to the accounts of the fight, treating it as both the frolic that it was as well as an ersatz battle, with tongue in cheek, of some military importance.

Despite the seriousness and somberness with which the soldiers approached their snowball wars, the most important aspect was the respite it provided from winter camp life. And minor injuries notwithstanding, there was little lingering resentment from the day’s fighting. Thousands of men, from virtually every regiment in the army, participated in what surely was one of the largest snowball fights in history. Though the Confederates thoroughly enjoyed the merriment of February 1863, and additional snowball fights of major magnitude would occur again before the guns fell silent, what lay immediately ahead for the boys in gray were the bloody battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg; grisly reminders that their snow fight had been only a brief interlude between nightmarish acts of war.

Jason H. Silverman recently retired as the Ellison Capers Palmer, Jr. Professor of History at Winthrop University and grew up not far from the scene of the Rappahannock Valley snowball battles of 1863.

Don’t Pelt Old Pete

During the winter of 1862-63, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s wife came to visit him and stayed close to the First Corps camps. Because she did not stay in the military camp proper, Longstreet rode to see her every morning. Longstreet’s ride carried him through the huts of the famed “Texas Brigade.” Every day that there was snow, the men of the brigade lined the officer’s street, where they “saluted him with a shower of snow-balls.” At first “Old Pete” took it in stride. But after a number of these occasions, he grew tired of the barrages. After the next snowfall, Longstreet approached the camp and found the Lone Star troops ready to let fly with their icy bombs. Before the Texans could unleash their volleys, “he reined up his horse, and said to them very quietly: ‘Throw your snow-balls men, if you want to, as much as you please; but if one of them touches me, not a man in the brigade shall have a furlough this winter. Remember that!’” According to his aide, “there was no more snow-balling for General Longstreet’s benefit.” –Kristopher D. White