In 1877 Yellowstone National Park played host to the U.S. Army’s war against the Nez Perce.

FOR MUCH OF ITS FIRST TWO CENTURIES THE UNITED STATES was bent on conquering the wilderness. Cities rose from bare ground, forests were shorn for timber, open fields were subdued by plow, and indigenous peoples were pushed aside. But a dramatic reimagining of this philosophical course was signaled on March 1, 1872, when President Ulysses S. Grant signed “An Act to set apart a certain Tract of Land lying near the Head-waters of the Yellowstone River as a public Park,” shielding more than two million wilderness acres (most in northwest Wyoming) from development and creating the nation’s first national park. Such were its panoramic vistas, violently beautiful geysers, unique geological formations, and ominously bubbling hot springs that writers had dubbed it “Wonderland.” But just five years after its creation, Yellowstone National Park played host to a final stage of the last major military campaign pitting the U.S. Army against Native Americans: the Nez Perce War of 1877.

Until that time, the Nez Perce, writes historian Elliott West, “were arguably the nation’s strongest and most persistent ally in the Far West”; a contemporary declared them “the best type of Indians.” The Nez Perce—or Nimíipuu, as they called themselves—provided timely aid to Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and then tried to follow a path that preserved their tribal dignity while accepting but moderating white encroachment. Though often viewed as a homogeneous entity, the Nez Perce were a deeply fractured society whose differences would factor into the 1877 conflict.

Their homeland in the Columbia River Plateau of the Pacific Northwest put the Nez Perce somewhat off the main currents of settlers. Tribal clans living along the Clearwater River regularly traveled to the Great Plains to hunt buffalo, while others bordering the Salmon and Snake Rivers were stay-at-homes content to fish. Christian missionaries found a tolerant reception among “upper” Nez Perce living in the northern home country but encountered opposition from the “lower” Nez Perce. But the deepest split in the tribe was caused by a series of U.S. treaties.

THE FIRST OF THE TREATIES WAS NEGOTIATED IN 1855 by Isaac Stevens, the first governor of Washington Territory, who cleverly kept the Nez Perce areas intact while dispossessing weaker neighboring tribes, thus muting Nimíipuu opposition. A second treaty, prompted by a fleeting 1863 gold strike, slashed tribal areas to 10 percent of what they had been. Its U.S. negotiators chose to assume that one of the few Nez Perce who accepted the treaty (a man known as “Lawyer”) spoke for the rest of the tribe; they maintained that the resulting agreement applied to all. The Nez Perce were now divided into a Treaty faction (those already living inside the designated reservation) and a Non-treaty faction (outsiders wanting better terms). The dissidents remained on the contested land and hoped the problems created by what they called the “steal treaty” would vanish.

The Non-treaty faction was a loose end that the U.S. government was determined to tie up. After the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, the Non-treaty headmen were given short notice to relocate onto the government reservation by choice or force. Nimíipuu leaders grudgingly decided to move, and the five affected tribal bands readied themselves for resettlement. For an embittered few, the years of humiliations sparked a violent frenzy against white settlements along the Salmon River in northwest Idaho Territory, on June 14–16, 1877, that saw 18 settlers killed and at least one raped. If the Non-treaty leaders had doubts about whether the U.S. government would respond to these aggressions, they were put to rest on June 17, when a force of more than 100 cavalry and militia attacked their camps in White Bird Canyon. The poorly led cavalrymen were savaged by 65 Nez Perce warriors, who killed 34 of them. With indiscriminate retaliation inevitable, the Non-treaty tribes evacuated the area, beginning on June 18. The U.S. Army pursued, forging the basic dynamic of the 1877 Nez Perce War.

By August 23, the involuntarily nomadic Nimíipuu— about 700 men, women, and children, including some 150 warriors— passed through what is today Yellowstone National Park’s west entrance. They entered without any apprehensions, though according to a western traveler named C. W. Hatch, many whites believed that they had “a superstitious dread of this hot water country, and never go into it.” The tribal member with overall responsibility at the time was Lean Elk (a.k.a. “Poker Joe”), highlighting an often misunderstood aspect of Nez Perce leadership.

When multiple bands of Nez Perce acted together, leaders were chosen in the moment, based on the critical skills needed at the time. Lean Elk, who had been chosen in early August to lead the group, was selected to succeed a warrior chief because of his familiarity with the Montana region and the lack of any imminent military threat. Chief Joseph of the Wallowa band of Nez Perce was a civil leader—not the master commander proclaimed by later writers. In fact there were times, according to a warrior present, when Joseph was “hard to persuade to stay in the fight.”

The U.S. Army’s chains of command, brimming with former Civil War officers, guaranteed there would be a lot of chefs in the kitchen. General William Tecumseh Sherman insisted that the Nez Perce merited punishment “as a tribe,” including the hanging of captured headmen. Under Sherman were the leaders of the principal military regions engaged in the conflict: Lieutenant General Philip Sheridan of the Division of the Missouri and Major General Irvin McDowell of the Division of the Pacific. Brigadier General Oliver Otis Howard (reporting through McDowell) commanded the Department of the Columbia in Oregon, which included the Nez Perce lands. Howard directed the pursuit, and, to marshal the force needed, Sherman promptly authorized him to ignore jurisdictional boundaries. This proved a difficult asset to deploy since different departments, following priorities that had nothing to do with the Nez Perce, often based their units far from the Nimíipuu caravan. What’s more, the Nimíipuu regularly cut telegraph lines, breaking Howard’s direct contact with the east and forcing him to travel by horseback to find telegraph stations that could get his messages to their desired destinations.

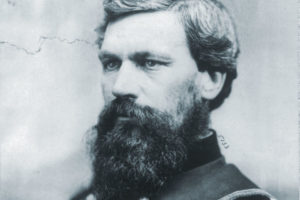

Howard was a Civil War veteran with a very mixed record. His poor flank security facilitated Lieutenant General Stonewall Jackson’s great success at Chancellorsville, but then his decision to hold the high ground south of Gettysburg secured the Union victory, for which Congress commended him. He was one of the wing commanders under Sherman during the famous marches through Georgia and the Carolinas. After the war he spent seven years running the Freedman’s Bureau, which Congress had established in 1865 to help millions of former black slaves and poor whites in the South, only to be hounded out by false charges of fiscal mismanagement. He returned to active military service in 1872, eager for professional redemption.

Negotiating with the Nez Perce was never an option for Howard, whose orders were to kill or capture them. He followed a tactical playbook that relied on superior firepower, requiring him to corner the Indians so that his arsenal, including light artillery and Gatling guns, could shred them into submission. But after the routing of U.S. forces at White Bird Canyon, it took Howard some time to concentrate a serious striking force, which allowed the Nez Perce to break contact and move off. The prospect of other tribes joining the Nez Perce was a constant worry for army leaders. Lacking any insightful intelligence about Nimíipuu politics, Howard authorized the detention of the Treaty warrior chief Looking Glass, a man of prestige and solid battle experience, solely on the assumption that he might defect. But the arresting party bungled the job, and the furious headman, who had been ready to sit this one out, joined the Non-treaty bands. With him came 60 warriors plus 16 gun hands from the nearby Palouse tribe.

The Nez Perce lingered in Yellowstone until September 6. Evidence suggests that during their sojourn they separated into two large groups and many smaller ones, mostly scouting, security, and hunting parties, moving in all directions. While their general course is mostly understood, firsthand accounts are spiked with ambiguous details. Only toward the end of their time in the park was there any urgency to their movements, because Howard’s pursuing column had virtually collapsed from exhaustion at Henrys Lake, 30 miles out from the park’s western entrance, on August 24.

HOW COULD A PROFESSIONAL MILITARY FORCE FALTER while the Nimíipuu men, women, and children pressed on? Part of the answer was certainly motivation. The soldiers were merely following orders, the Nez Perce fleeing for their lives. Just as important, the tribes were accustomed to navigating the challenging terrain, readily improvising to overcome wilderness obstacles; the army forces weren’t.

Howard’s need for firepower required wagons to carry the guns and ammunition, along with properly trained infantry. For long stretches of the chase, the soldiers had to carve roadways through areas one of his officers recollected as “a perfect sea of mountains, gullies, ravines, canyons.” Another remembered that the “slippery trail was almost impassable, filled with rugged rocks and fallen timber.” In contrast, the all-mounted Nez Perce, armed only with the weapons their warriors carried, easily traversed the familiar terrain and made better time. One tourist, Emma Cowan, described how they navigated a heavily timbered section of the park. “It was a feat few white people could have accomplished without axe or implements of some sort to cut the way,” she recalled. And when the pack animals got wedged between the trees, an old woman “would pound them on the head until they backed out.”

Cowan belonged to one of several tourist groups the Nez Perce encountered in Yellowstone. The Nimíipuu passage to this point had shown two faces. In settled areas they agreed to temporary truces that included formal purchases, while encounters with small civilian groups and individuals elsewhere often ended in killings for supplies, horses, and security. Once within the park the nearly three-mile Nez Perce column compacted, putting the conciliatory headmen in closer contact with the more aggressive scouting parties. It is estimated that eight or nine separate sightseeing groups, totaling at least 25 people, were in the park as the Nez Perce passed through.

of his people. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Although they had been warned that the Nez Perce were in the vicinity, the tourists refused to yield to what one of them termed “an old time Indian scare.” Two groups were overrun, one (seven men, two women) on August 24, the other (10 men) two days later. In neither case did the tourist groups offer resistance, though Emma Cowan’s husband, George, projected an overbearing posture that soured what had been a tense but peaceful encounter. The mixed-sex group of tourists was brought into one of the main columns already in motion through a rugged area and were forced to abandon their wagons and goods. Lean Elk warned them that some warriors were in a murderous mood because several Nimíipuu noncombatants had recently been killed. But that news didn’t stop two men in the party from escaping. A short time later, while the seven remaining tourists accompanied the caravan, several warriors rode over to shoot George Cowan and another man. Hit several times, Cowan fell with what seemed mortal wounds (he survived), but in the melee three more uninjured men fled into the brush and, like all tourist escapees, were not pursued. The warrior Yellow Wolf, in later acknowledging the incident, maintained that some Nimíipuu were “double minded” and blamed Cowan’s shooting on “the bad boys.” He also declared, “We did not want to kill those women.” They and the remaining male prisoner were eventually given broken-down horses, escorted to a safe area, and released. The other large tourist party the Nez Perce encountered was attacked without warning on August 26 and scattered. One person was killed, another wounded, and all had some fearful days in the wilderness before they reached safety.

In all, two tourists were dead, three were seriously wounded, and the rest scarred with nightmares. The Nez Perce encountered several nontourists in their security sweeps as well. Typically, army scouts and couriers were killed; civilians deemed useful were spared. One such survivor, a prospector named John Shively, was taken on August 23 and, according to his account, guided his captors along some obscure Yellowstone trails before he managed to escape on September 2. He was the source for the often repeated story that while in the park the Nez Perce were lost.

“We knew that park country, no difference what white people say!” insisted Yellow Wolf. What was true was that throughout the long marches, Nez Perce leaders constantly discussed the question Where are we going? Any hopes that the whites were not going to punish all Nez Perce were dashed after White Bird Canyon. The Nez Perce moved north and east to camp on the Clearwater River just within the official reservation boundary, where sympathetic Treaty Nimíipuu assisted them. The internal arguments seem to have been about whether to find a way to remain in the traditional homeland or continue to bison country to seek sanctuary with the historically friendly Crows.

CAMP SECURITY WAS UNCHARACTERISTICALLY LAX WHEN THE ARMY UNITS under Howard’s personal command attacked on July 11. Howard deployed his Gatling guns and 12-pounder howitzers, but to little effect as the warriors continually dispersed. “Killed today, there can be no fighting tomorrow,” declared one. They also adapted to their enemy, using infiltration tactics to neutralize one howitzer, and targeting officers when receiving attacks (the Nimíipuu proved excellent marksmen). The Clearwater combat extended into the next day, after which the Nez Perce, with their pony herd intact, moved off—buying time with a ruse negotiation. Army losses were 14 killed and 25 wounded; the Nez Perce had four dead and six wounded.

Thanks to Looking Glass’s fighting prowess, his counsel became paramount. The line of movement now extended east, with a majority agreeing to join the Crows, while a few still eyed the homeland. They maintained a solid lead on their pursuers and believed their Idaho-based nemesis would not follow, when, on August 8, they were struck at Big Hole, Montana Territory. The attacking force of 161 (under Colonel John Gibbon, assigned to Brigadier General Alfred Terry’s Department of Dakota) failed to capitalize on its initial success before the Nez Perce counterattacked. “Fight!” cried the warrior White Bird. “Shoot them down.” The end of this bloody day saw 34 U.S. soldiers dead and another 38 wounded, while 30 irreplaceable Nimíipuu warriors died with approximately 60 noncombatants. The exhausted U.S. Army force coiled protectively, while the Nimíipuu (pony herd intact) resumed their journey. They would engage in one more fight before they reached Yellowstone National Park, a partly successful spoiling attack on Howard’s camp on August 20 intended to scatter the army horses. Three days later the Nimíipuu entered the park, having learned from scouts that Howard’s pursuit had stalled. This allowed a relatively unhurried movement through the park to graze the pony herd and make good some of the wear and tear from the marching and combats—all buying time until the return of four emissaries sent to the Crows.

Howard left for Virginia City, Montana Territory (60 miles away), arriving on August 24. There he obtained much-needed supplies for his troops and used the town’s telegraph terminal to reconnect with his chain of command. (He was already smarting from local press coverage excoriating him for failing to close with the Nez Perce.) Howard contacted both McDowell and Sherman. Three days earlier he had sent a pessimistic update to McDowell complaining that his men were at the end of their tether and that he was not getting “prompt and energetic cooperation” from other commands. McDowell’s forwarded response was utterly unsympathetic. It was Howard’s responsibility to get the job done, he said, admonishing him to “be less dependent on what others at a distance may or may not do, and rely more on your own forces and your own plans.”

Howard advised Sherman that his column was “so much worn by overfatigue and jaded animals that I cannot push it much farther.” If he was hoping for a little understanding he got none. Sherman suggested that if matters were as described, Howard should “give the command to some young energetic officer” and let him direct the pursuit.

Howard shifted into full career-protection mode. “My duty shall be done fully and to the letter without complaint,” he assured McDowell. “I never flag,” he told Sherman. “It was the command, including the most energetic young officers, that were worn out and weary by a most extraordinary march.” (This didn’t prevent Sherman from dispatching an officer to relieve him, but the man chosen—actually older than Howard—got lost and never connected.)

Howard returned to Henrys Lake and on August 28 entered Yellowstone, securing some terrified tourists along the way. His supply and bureaucratic issues had given the Nez Perce six days of relief, though elements of his command—scouting parties of Native Americans under white command—remained, actively seeking the Nimíipuu. A small, vigorous force of Bannock tribesmen led by Stanton G. Fisher confirmed evidence of Nez Perce passage and even saw a distant camp readying to march, but they never got any closer than some outposts. The Bannocks, who were primarily motivated by an ancient enmity (they routinely slaughtered Nez Perce stragglers) and the promise of Nimíipuu plunder, eventually lost interest, reducing Fisher’s force from more than 50 to a dozen.

The failure of the scouting parties can be partially attributed to the difficulties of moving across the wilderness and to the intuitive skill of the Nez Perce in the art of misdirection. Centuries of internecine warfare made leaving false trails second nature to them, and they knew Howard could be fooled. Still, it would take one magnificent deception to get out of Yellowstone without confronting an army force positioned to block them.

The Nez Perce had three Yellowstone exit options: due north, through Mammoth Hot Springs; northeast, via Clark’s Fork; or due east, crossing the Stinking Water (now the Shoshone) River. The northern route was familiar; Nez Perce scouts, encountering army patrols there, had burned Baronett Bridge. The eastern route made sense only if the Crows were extending sanctuary. It’s unclear exactly when the Nimíipuu emissaries returned to report that the Crows would remain neutral, but historian Elliott West believes it was August 31. That left Clark’s Fork, opening the way to Canada. In all their movements the Nez Perce had made avoiding a fight their top priority, so the trick now was to make the army think their objective was the Stinking Water.

For the first time in the campaign a strong army unit would await them. With the Nez Perce columns entering his domain, Sheridan kept his telegraphers busy positioning units to block all exits from the park. About 360 men from the 7th Cavalry reached Clark’s Fork on September 1, even before the Nimíipuu began heading there. In command, reporting through Colonel Nelson A. Miles, was Colonel Samuel Sturgis, another Civil War veteran, who had performed well in the Antietam campaign but fumbled badly at Brice’s Cross Roads.

The Nez Perce, aiming to misdirect the enemy, allowed their column to be seen heading toward the Stinking Water crossing. After covertly reversing course, they milled their 2,000 ponies to obscure the critical breakaway point. An army patrol probing toward Stinking Water found a pair of recently killed courier scouts, suggesting that the two had encountered the main body. Another, across Clark’s Fork, declared the passage (just 20 feet wide in places) too narrow for large groups. Sturgis convinced himself he was blocking the wrong place and marched his command 20 miles south to Stinking Water, leaving no observers behind. So when the Nez Perce pushed their way down the passage to Clark’s Fork, there was no one to stop or even spot them. Afterward Sturgis reportedly exclaimed, “Poor as I am I would give $1,000 if I had not left this place.”

CANADA—AND SANCTUARY WITH THE SIOUX REFUGEES THERE—now appears to have been the Nimíipuu objective. This represented a doomsday scenario for army commanders, who believed that a Sioux horde was ready to swarm the border states to assist their Nez Perce brothers. (An exile Sioux council actually convened to consider such an action but refrained when informed that the Canadians would terminate their sanctuary if they did.)

The next 20 days of the Nez Perce exodus were marked by skirmishes with some of Sturgis’s pursuing army forces, who eventually gave up the chase, spent. Although the Nimíipuu escaped, they made a strategic error in dismissing Howard’s column. (They had derisively nicknamed its leader “General Day-After-Tomorrow.”) As long as it remained distant they felt relatively safe, so much so that the hard-driving Lean Elk was once again replaced as leader by the warrior chief Looking Glass, who maintained that Howard did not pose an immediate threat. On September 29 the Nez Perce made camp on Snake Creek near Bear Paw Mountain, intending to stay there a few days.

The instrument of their destruction was Miles, with 520 cavalry, infantry, and artillerymen. The ambitious colonel drove his force across plains and rivers, astutely located the Snake Creek encampment, and attacked on September 30. At the end of a hard day’s combat, Miles had (at high cost) effectively pinned the Nez Perce in place and, most important, scattered the pony herd. Many leading warriors, including Lean Elk and Looking Glass, died in the fighting. The bulk of the trapped party suffered greatly from the suddenly bitter weather, lack of supplies, and artillery. It was Chief Joseph who came forward to negotiate the October 5 surrender. His translated comments included the famous phrase: “I will fight no more forever.”

Miles’s cordon, however, was anything but airtight, as it allowed some 233 Nez Perce to find their way to Canada. (Some Crow extended kindnesses to them along the way, as, said one, “the Crow heart was Nez Perce.”) The Sioux welcomed them by providing food and clothing, but within a year most returned to the United States.

In 113 days the Nimíipuu had traveled 1,100 miles, crossed the Continental Divide three times, and ended up about 40 miles from Canada. A total of 418 Nez Perce shuffled into captivity. Miles and the late-arriving Howard (riding well ahead of his column) told them that they would eventually be returned to the official reservation, but Miles and Howard were overruled by Sherman, who was seconded by the War Department and subsequently walked back that promise. The mountain-loving Nez Perce were sent to an Oklahoma spot they called “the Hot Place,” where disease claimed more of them than Howard had. When they were finally allowed to settle on the approved reservation, the Treaty Nez Perce sometimes shunned them.

Chief Joseph came to symbolize the tribulations of his people, owing in large measure to Howard’s repeated references to him as their sole leader. His dignified bearing and commentary elicited much national sympathy and won some concessions for his people. But he was banned from his beloved Wallowa Valley and died in northeast Washington in 1904. Howard’s subsequent writings and memoirs of the campaign steadfastly shifted blame to inept subordinates and limp intradepartmental cooperation and claimed impossibly large enemy body counts. Most modern assessments conclude that he consistently underestimated both his opponent and his logistical requirements. Until his death he was rankled by contemporary news reporting that gave almost all credit for the final victory to Miles, who claimed the top army command in 1895.

The Yellowstone park sojourn came at an important moment in the Nez Perce odyssey. While the Nimíipuu kept a wary eye on Howard’s often immobile force, the real means of their downfall were being organized and facilitated via telegraph and railroads in a wholly different quadrant—technologies they never understood. Today a 1,170-mile National Park Service trail recognizes their journey.

Profound differences of culture, tactics, leadership, and outlook differentiated the Nez Perce from their U.S. Army pursuers. Yet in the greatest irony of the 1877 war, there was a shared sentiment of awe and reverence in the face of the raw power of “Wonderland.” An officer on Howard’s staff proclaimed that Yellowstone park held “truly the grandest scenery in America,” while a journalist along for the campaign doubted “if there is a place in all the world in which Nature is at once so mighty and so beautiful.” Even though, as Yellow Wolf recalled, “the hot smoking springs and the high-shooting water were nothing new,” one briefly held tourist never forgot the sight of the curious Nimíipuu “looking at the geysers in Fire Hole Basin.” MHQ

NOAH ANDRE TRUDEAU is the author of nine books, including, mostly recently, Lincoln’s Greatest Journey: Sixteen Days that Changed a Presidency, March 24–April 8, 1865 (Savas Beatie, 2016).

[hr]

This article appears in the Summer 2018 issue (Vol. 30, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Death and Decision in Wonderland

![]()