A mysterious woman of many names and dubious merit became a southern media celebrity

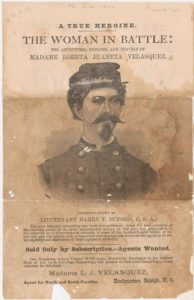

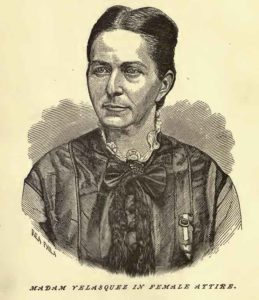

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]or 140 years, historians have puzzled over a book published in 1876 titled The Woman in Battle, the memoir of a woman calling herself Loreta Velasquez, one of her many names, who claimed to have dressed in a Confederate uniform, adopted the name Harry Buford, and fought in the ranks at First Manassas, Ball’s Bluff, Belmont, Fort Donelson, Shiloh, and more, until she put aside her uniform and spent the rest of the war as a Confederate blockade runner and spy in the North. Were her fantastic claims really true? The debate still goes on.

New evidence, much of it compiled from previously unexamined newspaper accounts, casts considerable light on this enigmatic woman’s real life. She reveals herself to be a prototype of the modern “media celebrity,” a master at manipulating the press to achieve publicity. Her real name at birth remains unknown. She used several aliases during her 80 years, first appearing on the record as Ann Williams in New Orleans in 1860, working as a teenaged prostitute. Just how or why she got the idea of posing as a Confederate soldier is unknown, but it is certain she deliberately courted discovery as a woman to attract attention and press coverage, which she probably hoped to parlay somehow into economic advantage.

She first did so in the fall of 1861 when she got off a train at Lynchburg, Va. Though she went by the name Mary Anne Keith at the time, she introduced herself as “Lieutenant Buford,” parading the city streets attracting attention as a woman in “uniform,” until she was arrested and sent to Richmond. Taken before Provost Marshal General John H. Winder for examination, she was soon released. She claimed to be a veteran of the First Battle of Manassas, fought that July.

She next showed up in New Orleans in April 1862, just before its capture by Federal forces, when she appeared before the mayor and voluntarily reported herself as Buford. After the Yankees occupied the city, she apparently returned to her old profession until the fall, when she conned a sympathetic couple into giving her lodging in their home. Shortly thereafter, she stole and pawned their jewelry and fled to the camp of the 13th Connecticut Infantry where she lived as the wife of a Private John Williams until she was arrested for larceny. Her day in court brought her renewed press attention in November 1862, and she expanded her Buford claims to include being wounded in battle at Shiloh serving the Confederacy. She was sentenced to six months in the Orleans Parish prison, where she identified herself as “Lauretta Clarke Williams,” born in Nassau, Bahamas.

Released in May 1863, she was ejected from New Orleans along with other suspected or undesirable people, and made her way to Jackson, Miss. She soon revealed that she had spent those months in prison crafting and honing a more detailed persona for herself and her Buford alias, as well as a plan on how to use her wits and experience to catapult herself into the spotlight as the Confederacy’s first media celebrity.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Velasquez was remarkably cavalier about omissions and contradictions as she retold her adventures[/quote]

The town of Jackson afforded Velasquez a good platform from which to reinvent and launch herself. Robert H. Purdom, a 25-year-old bachelor and member of the state legislature until he resigned in 1861, edited the Jackson Mississippian. She called on Purdom on June 4 or 5, and found him an eager listener. She emphasized that what she told him now was “a true account of her remarkable career.” First there was her name, which he wrote down as Mrs. Laura J. Williams, though she probably told him Lauretta. Gone were the other aliases.

She told Purdom that when the war broke out she was living in Arkansas, married to a man of Northern birth devoted to the Union, who left for his family’s home in Connecticut and, as she afterward learned, joined the Yankee army. That established her surname Williams as one by marriage and also refuted the claims in the New Orleans press that she had been sinfully cohabiting with John Williams of the 13th Connecticut. Outraged at her husband’s betrayal of her and the South, she vowed to “offer her life upon the altar of her country” and become a soldier. She explained to Purdom that was when she donned a Confederate uniform and assumed the name Buford. Now for the first time she gave her creation a given name, Harry, and implied that “he” was an officer.

As Buford—Purdom’s handwriting made the name look like “Benford,” and so it would appear in print—she went to Texas to raise an independent company of infantry that she subsequently took to Virginia. She said she led it in the engagement at Ball’s Bluff on October 21, as well as in other skirmishes, but when authorities attached her company to the 5th Texas Infantry, its surgeon discovered her sex and forced her to return to Arkansas. Purdom’s account contains no mention of any service at the First Battle of Manassas, service in western Kentucky, the fight at Belmont, or her experience as Mary Ann Keith, episodes that Velasquez would describe in her 1876 memoir The Woman in Battle.

Velasquez was remarkably cavalier about omissions and contradictions as she retold her adventures. Connecting herself with the 5th Texas, for instance, was probably just a random choice. In fact, there were no Texas units or independent companies at Ball’s Bluff, and the 5th Texas organized in Richmond on October 22, the day after that engagement.

Continuing to spin her story to Purdom, Velasquez said she stayed home in Arkansas until shortly before the Battle of Shiloh, April 6-7, 1862. That filled in the period from November 1861 to February 1862, which she had left blank in her earlier accounts of her war service. In the great battle at Shiloh, she told Purdom she saw her father, a Confederate soldier she did not name, on the battlefield but he did not recognize his daughter. A head wound, she claimed, sent her to the rear on April 7. After sending a note to her father, she went south to Grenada, Miss., to wait for him to come to her. Hearing nothing from him, she went on to New Orleans, where she fell ill and was still unwell when the Federals occupied the city.

Once recovered, she escaped the occupied city and went to the Louisiana coast, where she spent the ensuing months carrying letters in and out of the city for Confederate sympathizers and running drugs and uniform cloth through the Union naval blockade. After a black person informed on her, the Federals arrested her and took her to Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler. She appeared in woman’s attire but defiantly told him that she “gloried in being a rebel,” refused to take an oath of allegiance, and proudly declared that she “had fought side by side with Southern men for Southern rights” and would do so again. She told Purdom that Butler had denounced her as “the most incorrigible she-rebel he had ever met with” and sent her to prison for three months. Following her release, she kept corresponding with Confederates outside Federal lines, and again the Yankees arrested her. Butler sent her to a “dungeon” to languish a fortnight “on bread and water,” after which the Federals put her in the state prison as “a dangerous enemy.”

Coincidentally, the 13th Connecticut was in the city, and her Yankee husband, Williams, whom she now said was a lieutenant not a private, sent to ask if she would see him. She refused so long as he wore the hated blue, but he came to her cell nevertheless and insisted that she rejoin him, promising to secure her release if she would just take the oath. Then he said he would resign his commission and take her home to Connecticut. When she refused, he left her to her fate, and when Butler’s successor, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks, assumed command in New Orleans, he kept her in confinement until May 17, then he sent her away with other registered enemies.

Velasquez continued to create clouds to obscure the facts. In her trial for theft before the provost court in New Orleans in November 1862, she had put her name as Lauretta Williams on record and described her wholehearted support for the Union. At that time she represented her liaison with Private Williams as a respectable marriage and evidence of her Union patriotism, and the press had made note of it. To Purdom she spurned Williams as a Yankee brute, proving her Confederate solidarity. And she credited her arrest to her Confederate activities rather than to stealing. Thus, she separated herself from that traitorous Ann Williams imprisoned for larceny.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Velasquez continued to create clouds to obscure the facts[/quote]

As for those embarrassing six months in the parish prison, she cleverly changed the cause and made herself a martyr to Butler’s wrath, the bit about a bread and water diet being an inspired embellishment. Confederates universally demonized Butler after his famous general order in May 1862 that any New Orleans woman who behaved rudely to a soldier would be treated as a “woman of the town plying her avocation,” coded words for prostitution. Southerners had immediately dubbed him “Beast Butler,” and Velasquez shrewdly calculated her story of victimization by the “Beast” to gain even more credence and sympathy. She might present herself as a victim, but never as weak or helpless.

In closing her account, Velasquez told Purdom that on arriving in Jackson, she joined the surgeons’ staff of an infantry brigade and intended to “render all the assistance in her power” to Confederate wounded in the forthcoming struggle for Vicksburg. That meant acting as a nurse or caregiver, which implied that she would not resurrect Harry Buford in the immediate future. Purdom swallowed her story completely and offered it to his readers in the June 6, 1863, edition of the Mississippian.

He called her “a lady whose adventures place her in the ranks of the Mollie Pitchers of the present revolution,” and claimed “her whole soul was enlisted in the struggle for independence,” also admitting that he found her “good looking and in speech and manner a perfect lady.”

Purdom’s article was the first interview Velasquez gave directly to the press. If Lauretta hoped to get her own version on record, while countering damage done by the New Orleans papers covering her trial the past November, she estimated the press brilliantly. Disseminated through newspaper coverage, Velasquez’s creation was available to a quarter million or more Confederates either by reading or by word of mouth. It would gain even more circulation in 1864, when Felix G. DeFontaine published his Marginalia; or, Gleanings From an Army Note-book, a compilation of newspaper articles in which he included an edited version.

Velasquez and Harry Buford were soon back in public notice on a scale vastly larger than before, even though Purdom misprinted her alter ego’s name as Benford. Though she spent the next two weeks in Jackson, there is no evidence of any effort to become a nurse with the army. Her claim of caring for the wounded, like her protest of being persecuted by Butler, was just another calculated tug at the sympathy of potential benefactors. Rather, she had now framed a plan to capitalize on past publicity and the more fully realized story appearing in the papers. She hoped President Jefferson Davis would commission her as Lieutenant Buford, making her the first woman in American history to become a commissioned officer. She acquired gray fabric and shiny brass buttons, with which she made something approximating military pantaloons and perhaps a short uniform-style jacket.

Velasquez left Jackson as soon as she finished her “uniform,” probably with copies of the Mississippian article in hand to show, and traveled first east to Meridian, and then south by rail to Mobile, arriving on or before June 16, 1863. The Mississippian interview had appeared in the local press three days earlier, so the city was primed when she donned her gray suit and paraded its streets just as she had in Lynchburg in 1861, identifying herself the famed Lauretta Williams. For the rest of the summer she deliberately called attention to herself, proof enough that discovery was always her goal. She gained nothing if her masquerade succeeded but much attention if it did not.

From Mobile she wrote to the War Department in Richmond soliciting a commission and evolved her identity further by signing as “Mrs. Lauretta Jennett Williams.” She also mentioned that she already used the alias “H.T. Buford” and gave a return address in Mobile. She soon returned to Jackson, however, perhaps to inspire more press coverage in the Mississippian, but she left troubling questions behind. A woman dressed as a man aroused suspicion, and impersonating an officer was a serious matter. The local provost marshal felt uneasy about her, and shortly after she left Mobile he issued an order for her arrest and notified Richmond as well.

Unaware of the trouble brewing, Velasquez displayed herself and her new uniform back on Jackson’s streets on June 24. One local man described her that day on the sidewalks walking with “a very perceptible strut, and a trifle of a swagger,” and later that day called her “a rara avis,” adding that she was “a well made, but not pretty, Confederate lieutenant, of the genus femina.” He and everyone else in Jackson knew her story by now, and though it was certainly romantic, he for one did not like the imposture. “We admire angels in calico, but we never could see the charm of dressing up ‘the last and best gift of heaven’ in pantaloons, though the trowsers were of nice Confederate gray, with brass buttons thrown in,” he wrote. “It may be a splendid opportunity for showing a well turned ankle, but ‘while it makes the unthinking laugh, it cannot but make the judicious grieve.’”

Coincidentally, the next day the War Department in Richmond received her application, which immediately aroused suspicion, and a clerk docketed her letter with the notation “alias H.T. Buford Lt. C.S.A.” Within hours a telegram sped west ordering her detained and sent to Richmond for investigation. Thus, when she returned to Mobile, the provost marshal arrested her and put her on a train for Virginia, still in her uniform. They reached Richmond on the morning of July 1, when her guard took her immediately to the office of Brig. Gen. John H. Winder, who apparently did not connect her to the incident of 1861, when she had appeared before him as Mary Anne Keith, aka “Buford,” in military uniform.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Confederates read of “a female lieutenant” imprisoned in the capital[/quote]

The Mississippian story had appeared in Richmond’s city papers a dozen days earlier, so editors—and surely Winder’s office—ought to have known her as Laura J. Williams, but when notice of her arrival hit the press, the Richmond Enquirer misidentified her as Alice Williams. The rest of the capital newspapers copied the Enquirer’s mistake, and Velasquez apparently did nothing to correct them. Given her appetite for publicity, Velasquez may have allowed the erroneous Alice to stand when she saw how much press coverage she got.

With Winder, she again eschewed trying for sympathy and instead adopted what someone in the War Office regarded as “an independent air,” warning that if he tried to press charges against her, she would “claim foreign protection” as a British subject over whom Confederate authorities had no authority. Thus, for the moment at least, she persisted in her claim that she had been born in the Bahamas. The bluff failed, however, for Winder concluded that “there was something wrong about her” and ordered her sent to Castle Thunder, the city’s prison for suspected disloyal citizens, spies, and political prisoners. Meanwhile, the press learned of her arrival, not doubting that she was the Mississippian’s Laura J. Williams, as she claimed, for she seemed, in the Enquirer’s words, “not of the build to be frightened easily by either gun or goblin.”

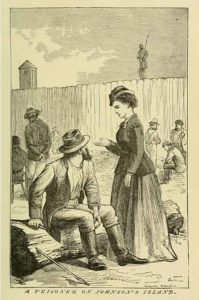

The next day, newspaper coverage of her stay in Richmond commenced unsympathetically with that same paper’s observation that she was “not quite as pretty as the romance of her case might admit.” Still, so far as anyone knew, no specific charges faced her other than posing as a man and officer. Within days Confederates read of “a female Lieutenant” imprisoned in the capital. The appellation began to stick.

“The female lieutenant” was soon out of prison, and became an object of curiosity to press and public alike. For a few more months she remained a Confederate celebrity before she married a man just as mysterious as she was, went north with him when he deserted to the Yankees, and developed entirely new adventures working in a Union ammunition factory, selling life insurance, and even trying to become a Union spy. When the war ended she still had almost 60 years ahead of her, years that she filled with entirely new masquerades and schemes that made her the most ambitious female con artist of her time, all the while enhancing and evolving her fictitious war history, even after her book The Woman in Battle appeared in 1876.

William C. Davis is a former editor of Civil War Times, a prolific Civil War scholar, and the former director of programs for the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Tech. This article is excerpted from his most recent book, Inventing Loreta Velasquez: Confederate Soldier Impersonator, Media Celebrity, and Con Artist, published in 2016 by Southern Illinois University Press, and here published by permission. Copyright © 2016 by William C. Davis.