The subtitle neatly summarizes this extraordinary book. To chronicle the Founding Fathers who served in the first Congress to function under the Constitution, award-winning historian Bordewich has availed himself of the First Federal Congress Project. That enterprise has cataloged nearly every diary, letter, and newspaper account relating to the proceedings of the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives of 1789-91, and Bordewich has mined those rich veins well. With fluid, fluent style he encapsulates the period’s sweep, punctuating his broader narrative with colorful detail, bringing acerbic debates into clear focus. History textbooks often gloss over that long-ago session’s key actions, such as the passage of the instrument that became known as the Bill of Rights, the choice of a location for the national capital, the creation of the United States Bank, and federal assumption of states’ war debts.

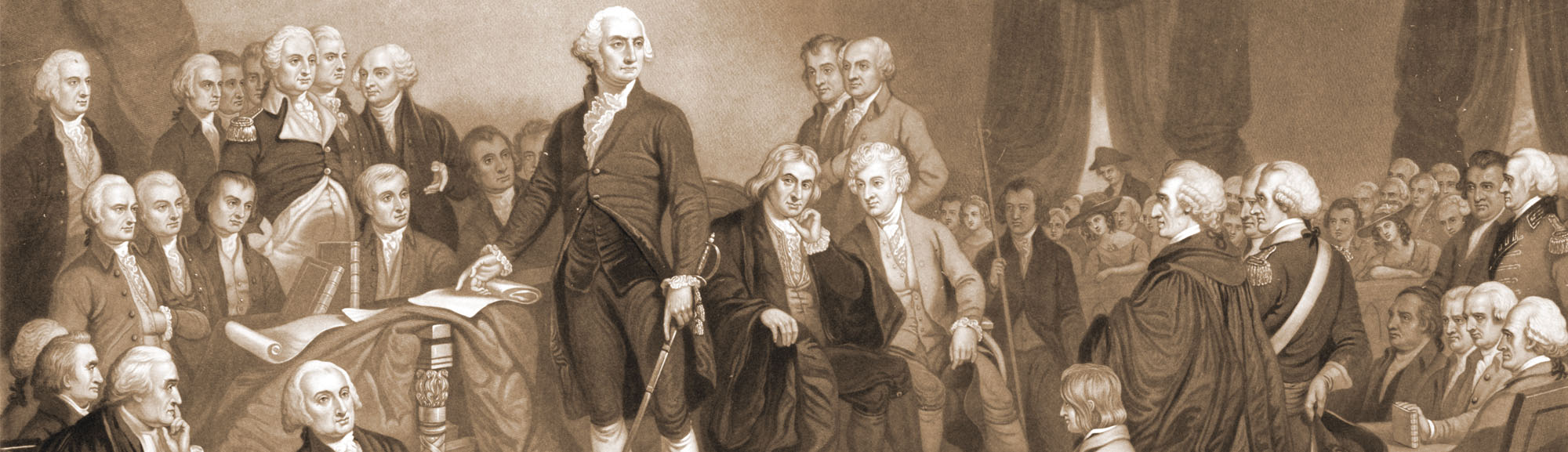

Bordewich skillfully humanizes the back-and-forth that led to these decisions, portraying great men rolling up their sleeves and politicking, at times surreptitiously. He shows us President George Washington, first at Federal Hall in New York City and later at Congress Hall in Philadelphia, attempting to remain above the fray while secretly communicating his wishes to House leader James Madison. Madison, who begins as a Federalist, assumes anti-Federalist positions on whether the Constitution demanded that readers apply a strict or a loose construction. Today’s Broadway hero, Alexander Hamilton, battles to set the nation on sound financial footing against a parochial host of egocentric congressmen. And prickly Vice President John Adams, lately frowned upon by historians for his lack of tact and overreaching approach to a job he demeaned, actually casts tie-breaking votes. Among the revelatory asides: Madison feared the power of the Senate more than the presidency; constant contact with that body’s members grated on Adams.

Washington usually was able to mask his violent temper with sangfroid, but when senators voted to delay action on his request to propose an Indian treaty, the commander in chief stalked out with “sullen dignity,” later declaring he “would be damned if he ever went there again.”

The author deftly draws his reader into the realities of late 18th-century America, animating settings and conditions that made life in general and political service in particular exasperating—roads muddied by rain and dust-rutted when dry, abominable city summers, cramped meeting rooms, and, in Congress, fractiousness that penetrated all the way down to individual state delegations. Nonetheless, the first Congress rendered decisions that set the nation on course to achieving its potential in ways the founders never envisioned. Bordewich writes in such a lively manner one feels like an uninvited but enthralled observer overhearing the debates of that auspicious assembly.

—Richard C. Culyer III is professor emeritus at Coker College in Hartsville, South Carolina.

This review was originally published in the September/October 2016 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.