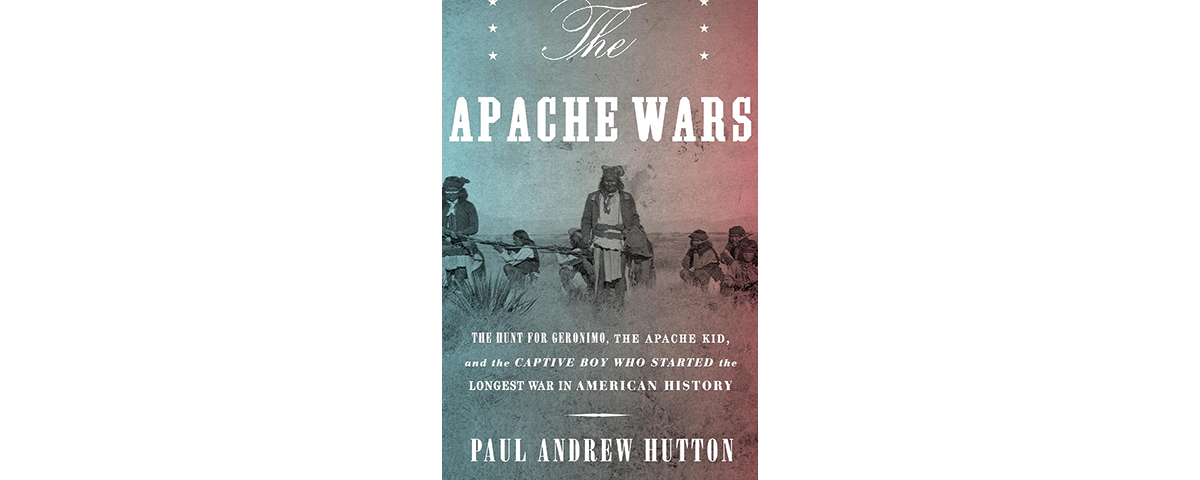

The Apache Wars: The Hunt for Geronimo, the Apache Kid and the Captive Boy Who Started the Longest War in American History, by Paul Andrew Hutton, Crown Publishers, New York, 2016, $30

Aravaipa Apaches abducted young Felix Ward from his stepfather’s Arizona ranch in January 1861, but 2nd Lt. George N. Bascom, determined to free Felix, blamed Cochise’s Chiricahua Apaches. That unfortunate mistake and the lieutenant’s subsequent actions, including the arrest of Cochise, led to the “Bascom Affair,” which had killing enough on both sides and triggered what author Paul Andrew Hutton calls “the longest war in the history of the United States.” Apaches had fought Americans earlier, but now came the final struggle for Apacheria, which didn’t end until Geronimo’s final surrender in late summer 1886. The boy, who grew up Apache and became known as Mickey Free while serving as an Apache scout for the U.S. Army, not only played an important role in that war but also received plenty of blame for starting it. That makes about as much sense as blaming Charles Lindbergh’s baby for his own kidnapping, but blame or no blame, one-eyed Free is an intriguing character around whom to wrap a narrative. That’s not to say he is the whole story—far from it, as Free’s violent and unforgiving world included Apaches like Cochise, Geronimo, Victorio, Lozen and the Apache Kid; scouts like Al Sieber and Tom Horn; generals like O.O. Howard, George Crook and Nelson Miles; and Indian agents like John Clum.

Before Bascom botched up the works in 1861, Apaches were hardly at peace. They had raided in New Mexico Territory (which included future Arizona) and northern Mexico and had fought Spanish, Mexican and American soldiers. For instance, U.S. soldiers battled Jicarilla Apaches in the 1850s, as Hutton writes about in this issue of Wild West. These earlier Apache wars didn’t make the cut for his 500-page book. That said, Hutton does give readers excellent coverage of the long final war, including the peace within the war that frontiersman Tom Jeffords and General Howard negotiated with Cochise; Victorio’s War within the war and his death at the hands of Mexicans at Tres Castillos; the Camp Grant massacre, in which a 146-man force of mostly Papago (Tohono O’odham) Indians and Hispanics from Tucson slaughtered some 125 Apaches; the fight at Cibecue Creek over the arrest of a prominent Apache medicine man known as the Dreamer; the breakouts of Geronimo and others at the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation; and the pursuit of Geronimo and his small band of followers, which involved as many as 4,000 U.S. soldiers.

The author also devotes plenty of space to the elusive Apache Kid, a onetime scout for the Army who as “the last free Apache” became a hunted man long after the Chiricahua people were removed from San Carlos to the East and the Apache wars were finally over.

Hutton sheds light on a cast of larger-than-life characters, most of whom were involved in considerable infighting. Geronimo, for one, was at odds with many fellow Apaches, and while he and his small band were defying one-quarter of the U.S. Army, his own people viewed him more of an outcast than a rebel with a cause. “His followers had been imprisoned in the East, while the Warm Springs people at San Carlos and Alchesay’s people at Fort Apache hated him for the misery he had brought upon them,” writes Hutton. “Even Mangas, still at large with a handful of followers, refused to join with him against their common foe.” The generals didn’t always see eye to eye with each other or with the various Indian agents on the way the Apaches were treated, the most notable feud pitting the ruthlessly efficient Miles, called “a brave peacock” by Theodore Roosevelt, against Crook, who Hutton says was “self-centered” and burdened with “self-righteous moralism.” Those citizens of Arizona Territory who generally believed that extermination of the Apaches was the proper course found fault with Indians and soldiers alike.

Hutton goes over much familiar ground, at least to students of the subject who have read such outstanding works as Edwin R. Sweeney’s Apache trilogy, the last of which was the 640-page 2010 tome From Cochise to Geronimo: The Chiricahua Apaches, 1874–1886. But Hutton, a history professor at the University of New Mexico, has his own take on things and is an engaging storyteller who has won numerous awards from Western Writers of America and the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. With his epilogue Hutton puts a nice finishing touch on the fascinating saga, relating what happened to many of the colorful characters after the wars (well, at least the Apache wars) were over. A sampling: Tom Jeffords never married and died a hermit in 1914; Nelson Miles died of a heart attack in 1925 while treating his grandchildren to a Barnum and Bailey circus; Chatto, a Chiricahua war chief who became a scout, died in a car crash on an icy reservation road in 1934. Mickey Free? Hutton says he died sometime in the spring of 1914 and that “the white world took no note of his passing.”

—Editor