In 1675, some 55 years after English separatists later known as the Pilgrims had founded Plymouth Colony (in present-day Massachusetts), newsletters began appearing in London describing horrible atrocities committed by Indians against the New England settlers. The reports told of lightning raids on towns by hundreds of warriors, barns and houses burned to the ground, farmers tomahawked in their fields, colonial militia columns wiped out in ambushes, women and children taken captive, and worse.

While some questioned the veracity of the initial reports, the unrest quickly flared into a broad and bloody armed conflict. Known today as King Philip’s War (after the primary Indian war leader), the conflict stretched from 1675 to 1678 and was the subject of several important Puritan works, among them the Rev. William Hubbard’s The History of the Indian Wars in New England From the First Settlement to the Termination of the War With King Philip in 1677; Benjamin Thompson’s “New England’s Crisis,” the first epic poem written in North America; and the Rev. Increase Mather’s A Brief History of the War With the Indians in New England. The war has intrigued historians ever since.

‘But a small part of the dominion of my ancestors remains. I am determined not to live until I have no country’

King Philip’s War was not a localized clash like the Pequot War of the 1630s but full-scale warfare involving most of the New England region and many of the indigenous tribes, a total war that made no distinctions between warriors and civilians. And it was not certain the colonists would win. The war ended the largely stable and, in many ways, mutually beneficial relationship between colonists and Indians that had endured some five decades.

It was also an especially bloody war—the bloodiest, in terms of the percentage of the population killed, in American history. The figures are inexact, but out of a total New England population of 80,000, counting both Indians and English colonists, some 9,000 were killed—more than 10 percent. Two-thirds of the dead were Indians, many of whom died of starvation. Indians attacked 52 of New England’s 90 towns, pillaging 25 of those and burning 17 to the ground. The English sold thousands of captured Indians into slavery in the West Indies. New England’s tribes would never fully recover.

The war not only caught the eyes of English readers, it also caught the attention of recently restored British King Charles II, who sent envoys to assess the situation in New England. Plymouth Colony, the flash point of the war, had not initially sought a royal charter; Charles gave it one. He later dissolved the United Colonies of New England, a military alliance formed to adjudicate disputes among the colonies and to direct the course of any wars from Boston. As royal governors took charge, the New England colonies lost the freedom to manage their own affairs, which they had enjoyed since the 1630s. People used to ruling themselves no longer did. The consequences would stretch into the next century and beyond.

As with so many wars, the casus belli in this case was a comparatively minor event, the murder of a respected elderly “praying Indian” (Christian convert) named John Sassamon, a Wampanoag, or Massachusett, man who straddled the tense psychological fringe between the two cultures. Sassamon had studied the tenets of Christianity under John Eliot, the foremost Puritan missionary to the Indians of New England, who had helped found 14 “praying towns” of converted Indians and had translated the Bible into Algonquian. Sassamon could read and speak English and had evolved into a go-between, serving as both an interpreter to the colonists and a secretary to the Wampanoag sachem (paramount chief), a man known to the English as “King Philip,” for whom the war is named. Sachems were not kings in the European sense. Philip’s powers were limited, and he led his people at their sufferance. But he did speak for them and lead them in warfare. The colonists dubbed him Philip after Philip of Macedon, having given the name Alexander to his older brother. Philip accepted the name; his Indian name was Metacomet, but names among the Indians were provisional. It was their practice to change names when the occasion warranted.

In January 1675 searchers found Sassamon’s bruised body, the neck broken, beneath the ice of Assawompset Pond, near Middleborough, where he had supposedly gone fishing. He had earlier warned Plymouth authorities that Philip was preparing for war and planning an attack on one of the towns. A fellow praying Indian soon came forward, claiming to have watched from a distance as three Wampanoags beat and killed Sassamon. (It is worth noting the witness owed a gambling debt to one of the three.) All three were close counselors of Philip. Authorities arrested and questioned the men. They further ordered one of the suspects to approach the corpse, which started to bleed; folk superstition held that a murder victim’s body will bleed in the presence of its killer, and this “evidence” seems to have been decisive. At trial in June a jury found the three Indians guilty, and the men were sentenced to hang. Within days of their June 8 executions disaffected Wampanoags attacked and burned several homesteads in protest. On June 23, when the residents of the recently built Plymouth village of Swansea left their farms lightly guarded to attend a prayer meeting, Wampanoags emerged from the woods to loot several homes. A farm boy spotted several Indians running from one of the houses, raised his musket and fired a shot, mortally wounding one of the raiders. The following day Wampanoags killed nine Swansea settlers in retribution. King Philip’s War had begun.

It was a confused and unstructured war that had no front lines but was essentially a fight for territory, indeed for the future of New England itself. Except for the Pequot War, the Indians and the English had gotten along reasonably well until the 1660s. The English traded useful guns, ammunition and metal tools to the Indians mostly for beaver pelts, which merchants sold in Europe to feed a passion for beaver felt hats. The Indians did not own land privately, but they had a strong sense of collective tribal territory. If they were not using land to farm or hunt, however, they sold it willingly enough to the colonists to farm and establish towns. For a half-century the groups lived in proximity to each other, and the relationship remained stable.

As the English population increased, however, cracks began to appear on the surface. The English wanted more land and were going farther afield to lay claim to it. The settlements in the Connecticut River Valley, well to the west of Wampanoag country, were growing rapidly. The lands the Indians were willing to sell were dwindling all across eastern New England. The colonists often let their farm animals roam; inevitably some roamed into Indian cornfields, destroying crops the Indians depended on to get them through the winters. Prior to the outbreak of war Rhode Islander John Borden, a friend of Philip’s, met with the Wampanoag sachem to seek accord between the two groups. Philip stated the Indian case eloquently:

The English who came first to this country were but a handful of people, forlorn, poor and distressed. My father was then sachem. He relieved their distresses in the most kind and hospitable manner. He gave them land to plant and build upon.…They flourished and increased.…By various means they got possessed of a great part of his territory. But he still remained their friend till he died. My elder brother became sachem. They pretended to suspect him of evil designs against them. He was seized and confined and thereby thrown into illness and died. Soon after I became sachem, they disarmed all my people.…Their lands were taken.…But a small part of the dominion of my ancestors remains. I am determined not to live until I have no country.

Samuel G. Arnold, a 19th century historian and U.S. senator from Rhode Island, aptly described the statement as “the preamble to a declaration of war…a mournful summary of accumulated wrongs that cry aloud for battle.” The theme would haunt most of the Indian wars in North America until indeed, two centuries later, when the Indians no longer had a country.

As the attack on Swansea proved, the Wampanoags had not disarmed, as the colonial government had demanded. The raid panicked the colonists, and authorities in Boston sent a contingent of hastily assembled militia south to Swansea, as did Plymouth. The gathered militiamen numbered perhaps 200, facing an Indian force of unknown size. They initially engaged in skirmishes but no pitched battles. One group of 20 colonists ran into an ambush—a tactic that would ultimately claim hundreds of militiamen—by an overwhelming Indian force and escaped only by commandeering a vessel passing on a nearby river. The colonists had muskets, but so did the Indians. The Indians also had longbows that could drive an arrow straight through a thighbone. And when pursued, the Indians melted into the woods, making it difficult for colonists on horseback to follow.

While the militiamen survived this initial skirmish, it soon became clear such outings would accomplish little, as the Indians were hard to pin down. They knew the land and likely escape routes, and the swamps in which they so often took refuge were impenetrable to anyone not intimately familiar with them.

After Swansea the Indians swept down on Middleborough and Dartmouth. Like most New England towns Dartmouth had established garrisons—fortified strongholds in which residents could shelter. From there the settlers watched the smoke rise as the Wampanoags torched house after house and killed whoever had not retreated to the garrisons. They left most of the town in ruins. One garrison commander managed to persuade several dozen Indians—men, women and children—to surrender themselves on promises of safe conduct. Then, in a pattern that became common during the war, he transported them to Plymouth to be sold into slavery. The betrayal prompted further reprisals.

At the start of the conflict Philip acted alone, and the colonists took pains to ensure that the Narragansetts, New England’s most powerful tribe and neighbors to the Wampanoags, did not join the war. Philip moved northwest into Nipmuck territory, near Worcester. The Nipmucks had their own reasons to resent the colonists, and two of their sachems, Muttawmp and Matoonas, soon joined the fight and proved capable military leaders. Matoonas’ attack on the town of Mendon in mid-July left six settlers dead; a few weeks later Muttawmp hit Brookfield with 200 warriors, ambushing a small colonial force sent to reinforce the town. Nearby cavalry rode to the rescue at Brookfield, and no clear victor emerged, but there could be no doubt about what was happening: King Philip’s war was spreading, and every town in southern New England was a target.

That other tribes joined the spreading conflict does not mean the region’s Indians were working together in a united effort to drive the English settlers into the sea. The Mohegans, for instance, remained firmly aligned with the colonists throughout the conflict, while the Mohawks, farther west, exploited their alliance with the English to pursue ancient tribal rivalries along the Hudson River up into New England. Certainly, tribes were not “nations” in any modern sense; they were more collections of villages speaking the same language, connected by kinship and custom.

Nor did the war proceed in any organized way. The colonists fought by erecting garrisons in the towns and sending armed columns down forest trails after the Indians. The militias acted as though the laws of civilized warfare were in effect, as if the Indians would dutifully face them on a battlefield or retreat to strongholds that could then be properly besieged. The Indians did build palisaded forts, but they were just as apt to slip away when enemies approached.

The most effective tactic the colonists used was to burn Indian crops in the fields, but this was a two-way street. The Indians burned many barns packed with colonial harvests and killed or stole farm animals. The retaliatory raids persisted through 1675 and into the following year. The colonists pursued the raiders, but it took several costly ambushes for them to learn that a military column in thick woods was an extremely vulnerable target. The Indians were at home in the forests and repeatedly lured the colonists into traps. Only when Mohegan scouts led them through the woods did the settlers stand much of a chance.

In September 1675, on the Connecticut River near Deerfield, Muttawmp and his braves killed 71 colonial soldiers in a lopsided ambush called the Battle of Bloody Brook. Deerfield itself suffered repeated raids. Panicky and enraged, settlers began abandoning their towns and homesteads. Some called for the utter extinction of New England’s Indians.

This was the mood in which the colonists decided the Narragansetts could no longer be trusted. In December—accusing the Narragansetts of harboring hostile Wampanoags, fearing they would soon join Philip’s rebellion and ignoring a recently signed treaty of neutrality—a combined force of colonial militia entered Rhode Island and mounted a pre-emptive strike. It marked the war’s first traditional European-style campaign, in which a 1,000-strong army of colonists and allied Indians—the largest yet assembled in North America—besieged the Narragansett stronghold in the Great Swamp south and west of Narragansett Bay. The Narragansetts had not completed a defensive wall surrounding their camp, and the militia attacked at once, swarming into camp through a breech in the walls. When the smoke cleared, more than 200 of the colonial troops lay dead or wounded, but the militia had killed an estimated 300 Narragansetts and taken as many captive. Militiamen then burned the fort and destroyed the camp’s winter stores. Still, the majority of the Narragansetts, including their sachem, Canonchet, and many of his warriors, escaped into the frozen swamp.

The colonists declared the battle a victory, but it had pushed the Narragansetts firmly into the war on Philip’s side. Within weeks the surviving warriors, led by Canonchet, began raiding Rhode Island’s towns and killing its colonists.

Townspeople abandoned Lancaster in the wake of a February raid. The raiders next struck Medfield, only 16 miles from Boston, followed by a string of other towns. King Philip was hardly a factor by this time; the Indians on the march were Nipmucks, Narragansetts and people from other tribes led by such feared sachems as Muttawmp, Quinnapin and Monoco (aka “One-Eyed John”). By early 1676 it looked as though the Indians might just prevail.

And they might have, had they had the manpower. But the war had taken a toll. Every attack cost the Indians, often more than it cost the colonists, and there were more militiamen than warriors. By this time the colonists were making effective use of their Mohegan allies and taking the war to their enemy rather than sitting in garrisons waiting to be attacked—a policy proposed to colonial authorities earlier but rejected. A series of devastating attacks in March—one on a garrison just 3 miles from Plymouth proper, then one on Providence—changed their minds. A turning point came in early April when Canonchet was caught, handed over to his Mohegan enemies and brutally executed. He had sworn to fight to the end. For him it had come.

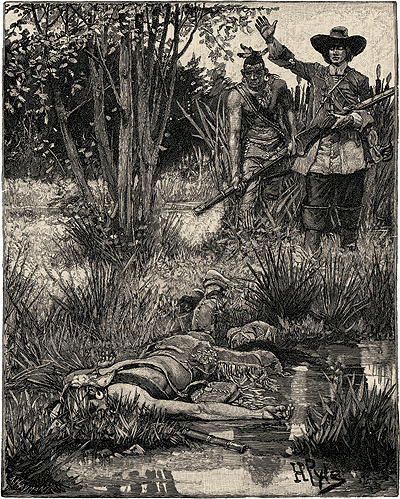

As colonial tactics became more sophisticated, Indian losses mounted. Finally, that August, Philip himself—having spent months on the run—was caught, cornered and mortally wounded by an Indian allied with the colonists. In keeping with English punitive tradition, the “treasonous king” was beheaded and his body quartered, the quarters hung from trees “here and there,” wrote one historian, “so as not to hallow a traitor’s body by burial.” Authorities in Plymouth ransomed Philip’s head and placed it on a spike atop a prominent hill overlooking town. It was said to have remained on display for decades.

The war was not quite over, however. By the summer of 1676 it had spread north into Maine and New Hampshire, where local Abenakis took revenge on some of the towns in which colonial traders had cheated them. Sporadic raiding persisted another year in the Maine interior.

By the time the fighting finally ended, the costs proved crippling for both sides. Hundreds of Algonquian-speaking Indians had been sold into slavery at an average price of three English pounds, and thousands more had been killed. Algonquian society as a whole would never recover. Colonial New England would recover, but at a snail’s pace—it took 100 years for the region’s economy to reach the prosperity levels of the prewar period. Worse yet, a long peace had been shattered, as had the possibility that in the New World diverse cultures might live peacefully side by side, in mutual tolerance, to one another’s benefit. Historian Russell Bourne quotes a current Narragansett leader’s embittered remark to anthropologist Paul Robinson: “So far as we’re concerned,” he said, “what the Puritans began here has never ended. The war’s still on.”

A frequent contributor to Military History, Anthony Brandt is the author of The Man Who Ate His Boots: The Tragic History of the Search for the Northwest Passage. For further reading he recommends The Red King’s Rebellion, by Russell Bourne; The Name of War, by Jill Lepore; and So Dreadful a Judgment, edited by Richard Slotkin et al.