In 1917 25-year-old Edwin Dunning set out to make history by landing his plane on the deck of a moving vessel.

HMS FURIOUS OPENED ITS ENGINES AND BUILT UP SPEED, steaming through the waters of the Grand Fleet’s wartime base at Scapa Flow. The British warship dwarfed the flimsy aircraft now easing into a parallel course alongside it. At the controls of the Sopwith Pup was Edwin Dunning, a 25-year-old squadron commander. That day—August 2, 1917—Dunning would either make history or die in the attempt. The task he’d set for himself was said to be impossible: He was going to land an airplane on the deck of a moving vessel.

In the opening years of the 20th century, the countries of Europe were sliding toward conflict that would mean the fall of empires and the deaths of millions. A naval arms race between Britain and Germany made war inevitable, but the British Admiralty ignored some weapons that would come of age in World War I. Submarine warfare, for example, was dismissed by some senior officers, who considered it “underhand” and even “un-English.” And so little was expected of aircraft in combat that when Orville and Wilbur Wright offered the Admiralty their airplane, the pioneering brothers were politely shown the door. In the minds of higher-ups in the Admiralty, an aircraft’s only possible use was in a reconnaissance role, spotting enemy ships, and the Royal Navy’s kite balloons already provided that service.

But one man of vision clearly saw the future course of naval warfare. French inventor Clément Ader predicted the flat-top aircraft carrier in his 1909 book L’Aviation Militaire. “An airplane-carrying vessel is indispensable,” Ader wrote. “These vessels will be constructed on a plan very different from what is currently used. First of all the deck will be cleared of all obstacles. It will be flat, as wide as possible without jeopardizing the nautical lines of the hull, and it will look like a landing field….Of necessity, the airplanes will be stowed below decks; they would be solidly fixed, anchored to their bases, each in its place, so they would not be affected by the pitching and rolling. Access to this deck would be by an elevator sufficiently long and wide to hold an airplane with its wings folded. A large, sliding trap would cover the hole in the deck, and it would have waterproof joints, so that neither rain nor seawater, from heavy seas, could penetrate below.”

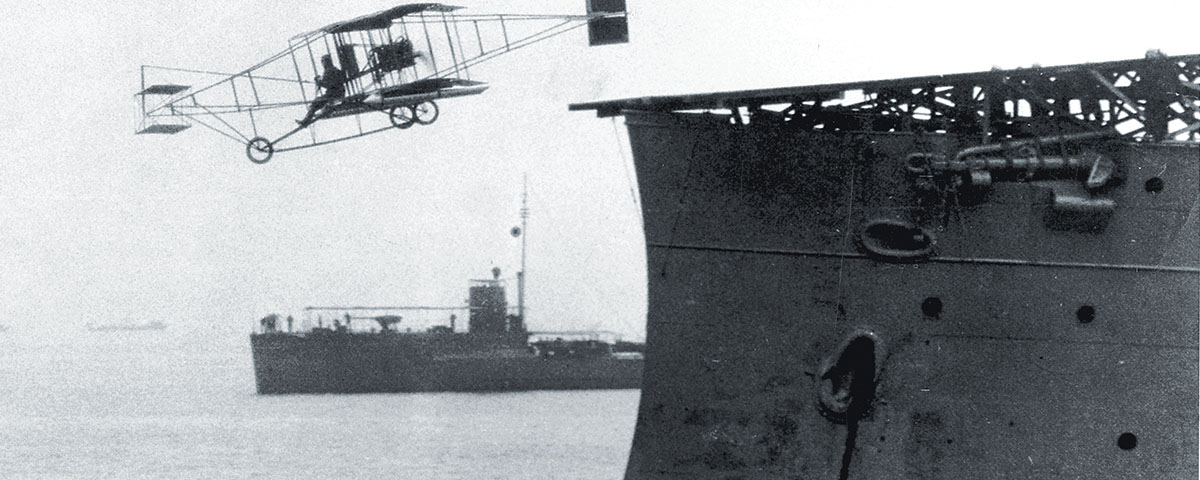

That same year Commander F. L. Champin, the U.S. naval attaché to Paris, picked up on Ader’s work and sent an enthusiastic report to his superiors. They responded by appointing Captain Washington Chambers to investigate the possible uses of aircraft in the U.S. Navy. Chambers had met Eugene Burton Ely, a civilian pilot from Williamsburg, Iowa, who was carrying out demonstrations of the Curtiss Pusher that astonished his audiences. This aircraft was little more than an open wood-and-bamboo frame with linen-covered wings and an engine with a propeller mounted behind it. Nevertheless, Ely agreed to attempt to fly his aircraft from the deck of a stationary ship.

A TEMPORARY 83-FOOT-LONG PLATFORM WAS BUILT ON THE BOW of the light cruiser USS Birmingham, anchored at Hampton Roads, Virginia. On November 14, 1910, Ely opened up his engine and courageously roared down the makeshift runway. The aircraft lurched off the ship and plunged toward the sea. As Ely frantically pulled at the controls of the Curtiss his wheels dipped into the sea, sending a spray of saltwater into his face. The plane finally responded and rose above the waves, but the wind quickly dried the salt on Ely’s goggles into a white film. With his vision impaired, Ely scrapped his intention to triumphantly circle the harbor and land at the Norfolk Navy Yard. Safely landing his Curtiss on a nearby beach, Ely proved that flying from a stationary ship was possible.

Ely would later land his Curtiss Pusher on the deck of an anchored ship. On January 18, 1911, he flew from Tanforan Racetrack in San Bruno, California, and landed on a temporary wooden platform on the aft deck of the armored cruiser USS Pennsylvania, anchored in San Francisco Harbor. The aircraft had been fitted with a tailhook, which caught ropes on deck that were weighed down with sandbags—a technique devised by Hugh Robinson, an aviator and circus performer—for the attempt. The Curtiss was turned around again, and Ely flew off the deck.

Tragically, Ely was killed on October 19, 1911, just two days short of his 25th birthday, while giving an aerobatic display in Macon, Georgia. He was too late pulling out of a dive and crashed into the ground. He jumped clear of the wreck, but his neck had been broken and he died minutes later. (Congress posthumously awarded Ely the Distinguished Flying Cross in 1933.)

Across the Atlantic, the Royal Navy was finally starting to take this newfangled invention seriously. On March 28, 1910, Frenchman Henri Fabre made the first successful flight by a powered seaplane, relying on a system of flotation devices that he had invented. The British followed the French development with interest. On May 9, 1912, Commander Charles Rumney Samson of the Royal Navy became the first pilot to take off from the deck of a moving ship. A temporary platform was built on the bow of the battleship HMS Hibernia, from which Samson flew his Short S.38 as part of the Royal Fleet Review at Weymouth on the south coast of England. The aircraft landed ashore, since landing on the deck of a moving ship was still considered impossible.

In 1913 the Royal Navy temporarily modified a cruiser, HMS Hermes, into a seaplane carrier by installing a canvas hanger and a crane for recovering the aircraft. The greatest weakness of the seaplane carrier was that it had to stop to lower and retrieve the seaplanes by crane. With the submarine being developed as a weapon, which made it a sitting duck for submarines.

HMS Furious had been built as a cruiser, but with a difference. In a bizarre piece of naval design, it was to carry two single 18-inch guns mounted fore and aft. At the time, they were the largest naval guns ever fitted on a ship. While the vessel was still under construction, however, it was decided that Furious would be converted to a seaplane carrier with a flying-off deck at the bow, so the bow gun was removed. The remaining 18-inch stern gun was not used very often, but when it was fired, the ship shook violently. Furious entered service in June 1917, just five weeks before Dunning’s historic landing on its moving deck.

EDWIN HARRIS DUNNING WAS BORN IN SOUTH AFRICA ON JULY 17, 1892. He was brought up in Eastbourne, England, and entered the Royal Navy as a cadet, being educated at the Royal Naval Colleges at Osbourne and Dartmouth. He served in the Royal Naval Air Service during World War I and flew from the seaplane carrier HMS Ark Royal at Gallipoli in 1915. On March 14, 1916, Dunning was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for having “performed exceptionally good work as a seaplane flyer, making many long flights both for spotting and photographing.”

Back in Britain, Dunning was promoted to squadron commander and attached to Furious, which was stationed with the Grand Fleet in Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, off the north coast of Scotland. Here he was put in charge of a squadron of seven Sopwith Pups and two floatplanes used for reconnaissance, based at an airfield that had been built for them at Smoogro, on the shores of Scapa Flow. At the end of a 19th-century stone pier there, a concrete and wooden structure had been built to support a crane used to lift the aircraft onto a primitive-looking raft, which was then towed by boat back to Furious. Should the carrier be at sea and too far from land, the pilots were instructed to ditch their planes in the water—and pray that they would be picked up. The aircraft were fitted with air bags to keep them buoyant as long as possible. As wasteful as ditching planes may have seemed, an airplane at that time cost little more than a single battleship artillery shell.

Dunning was impressed with the daring and skill of his young pilots. Before landing at Smoogro after a day’s training, the story goes, the pilots liked to fly alongside Furious, running their wheels along the edge of the 228-foot-long flight deck for amusement. They did this by “blipping” their engines—using a “blip-switch” to cut the ignition to some of the cylinders of the rotary engines, thus slowing their machines. This dangerous maneuver gave Dunning an idea. By flying his aircraft directly into the wind while alongside the carrier, he could equalize the speed of the ship and the airplane, then fly past the mast, funnel, and bridge, and—theoretically, at least—land on the flying-off deck. The one great hazard was the turbulence caused by the superstructure of the ship, but that didn’t deter Dunning.

The ship’s captain apparently decided that the test was worth the risk. Dunning would attempt to land on Furious while it was steaming at full speed. The ship was capable of doing 31 knots, but with just a 10-mile stretch of water in a busy anchorage full of ships, the captain could only make 26 knots. It would have to do.

ON AUGUST 2, 1917, DUNNING STARTED THE ENGINE OF HIS SOPWITH PUP and took off from the airfield at Smoogro. The wind was 21 knots—less than the 25 knots that he had hoped for, but at least the sheltered harbor of Scapa Flow meant that there were no high waves to make the carrier roll, allowing for a less dangerous landing. Dunning wheeled his plane about and set off in pursuit of Furious, careful to avoid the smoke billowing from its funnel. Coming alongside the ship, he regulated his speed until the ship and the airplane were synchronized.

The turbulence from the ship’s superstructure buffeted the light plane as Dunning approached the flying-off deck. He carefully lowered one wing to turn the aircraft, knowing that if he lowered it too far the wing might hit the runway and make him crash. He maneuvered the Pup over the deck, bracing himself for the most crucial part of the landing. There were no arresting wires to stop the plane. Dunning’s landing depended on ropes, fitted to the wings and tailplane, with loops at the ends, which the waiting deck crew sprinted forward to grab as Dunning cut his engine. They dragged the Pup down to the deck of the ship, lifted Dunning out of the cockpit, and carried him along the deck on their shoulders, triumphant. The impossible had been achieved.

Dunning had carried out his experiment without the knowledge of his superior officers. When word reached them, Dunning was eager to demonstrate to the Admiralty what the airplane could do, presenting its potential as a new weapon of war and so much more than merely the eyes of the fleet. He planned to involve at least one other pilot in his official attempt. The trial was set for the following Tuesday, August 7, 1917. At 1330 hours Dunning roared down the flying-off deck of Furious as it steamed through Scapa Flow. He soared above the ship, circling around before attempting to land on its deck. Dunning made his approach, flying parallel with the ship before side-slipping around its superstructure to land on the deck at 1400 hours. But he’d come in too steep, and the airplane was damaged when it landed.

Dunning’s number two pilot, Flight Commander Geoffrey Moore, was waiting his turn in another Pup on deck, its engine running and ready to take off. Dunning, unhappy with his previous landing, asked Moore to stand down. Moore obliged, and Dunning climbed aboard, opened the throttle, and took off. Dunning had informed the deck crew that this time he was going to try to land the aircraft without their help.

He repeated the maneuver, slipping over the center of the deck, but he was too high and too far forward. Dunning waved away the deck crew and opened up the throttle once more. But the engine stalled and the airplane fell onto the deck, landing heavily on its right wheel. A sudden gust of wind caught the frail aircraft and flipped it toward the starboard side of the deck. The deck crew frantically ran after it, but they were too late, and Dunning’s Pup fell over the side of the ship and into the sea. No rescue boat had been detailed to follow the ship in case of accidents. Circling back, the large, fast-moving Furious took 20 minutes to rescue Dunning. By the time it reached the broken airplane, kept afloat by the airbags in its tail, Dunning—apparently knocked unconscious by the impact of the crash and drowned—was dead, still in the cockpit.

The Admiralty ordered all deck landings to stop immediately, but its commissioners met later that same year to discuss the future of aircraft in the Royal Navy. They decided that flight decks should be at least 300 feet long and the full width of the ship. Also, as Clément Ader had predicted, they proposed to build a flat-top aircraft carrier, HMS Argus. The aircraft carrier was born.

DUNNING WAS BURIED WITH FULL MILITARY HONORS AT ST. LAWRENCE’S CHURCH, Bradfield, Essex, next to his mother, who had died three years earlier. A memorial raised to him in the church includes these words:

“The Admiralty wish you to know what great service he performed for the Navy. It was in fact a demonstration of landing an Aeroplane on the deck of a Man-of-War whilst the latter was under way. This had never been done before; and the data obtained was of the utmost value. It will make Aeroplanes indispensable to the Fleet, & possibly revolutionise Naval Warfare.”

The inscription on the memorial concludes with the words of Dunning’s captain: “I shall never cease to admire & regret him. He was so keen and full of enthusiasm & such an excellent capable fellow in every way. Both officers & men serving under him deeply feel the loss of so fine an officer and gentleman.”

Dunning was mentioned in dispatches on October 1, 1917. A memorial stone was raised on the beach near Smoogro in Orkney to commemorate his achievement, but it is not easily accessible and the inscription is now almost illegible. On August 2, 2017—the centenary of Dunning’s historic landing—the Royal Navy unveiled a new memorial in the HMS Royal Oak Memorial Garden. Looming large in the background was the newest and largest-ever ship of the Royal Navy, the carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth, then undergoing sea trials. It was a fitting tribute in honor of this pioneer of naval aviation, who changed the face of modern warfare forever. MHQ

TOM MUIR is a historian and author from the Orkney Islands in Scotland. He is currently working with Nicholas Jellico and Stephan Huck on a book tentatively titled Honour and Deceit: The Scuttling of the High Seas Fleet, Scapa Flow, 1919, which will view the event from the perspectives of the British, the Germans, and the Orcadians.

[hr]

This article appears in the Winter 2018 issue (Vol. 30, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Birth of the Aircraft Carrier

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!