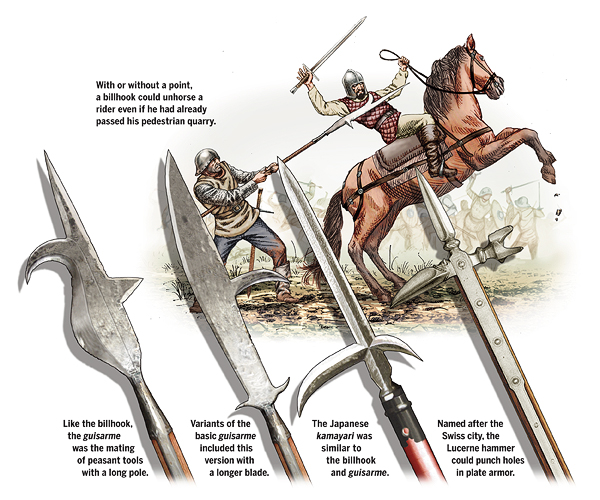

Pole-arms span a variety of shapes and purposes, most designed to give the foot soldier an advantage—or at least a fighting chance—against a mounted opponent. The billhook, mainly used in the British Isles, gave the infantryman several options. The broad blade was primarily an ax with which to slash a rider or his horse. Protruding from the opposite side was a pointed hook, or cleek. With it the foot soldier could punch a hole through the enemy’s armor or, as the horseman rushed by, hook and pull him from the saddle, then hack him with the blade.

Although shorter than most other pole-arms, at 5 to 9 feet, the English bill remained a weapon of choice among the men for whom it was named, even into the gunpowder era. At the 1513 Battle of Flodden, for example, bills and bows predominated among the English, who prevailed against Scottish pikes. The principle of hooking a mounted opponent was not unique to the bill, however. The guisarme, used on the Continent between 1000 and 1400, combined a broad spearhead with a hook off to one side. The bec de corbin (“crow’s beak”) had a sharp hook on one side of its spearhead and a hammer on the other, as much for balance as for battering an unhorsed opponent. A variation known as the Lucerne hammer bore a four-pronged head with which to punch in plate armor or further injure one’s opponent. Lending a Far East touch was Japan’s kamayari, with opposing hooks for snagging mounted samurai.