The fortunes of war are hardest on the vanquished, but for a cadre of Athenian commanders during the Peloponnesian War, victory proved fatal.

Present-day Greece may be beset with problems, but the nation is stable in comparison to its tenure as a conglomeration of city-states, when the cradle of civilization was riven by civil strife. The pivot point in the struggle for regional dominance came during the 431–404 bc Peloponnesian War, which pitted the ascendant Delian League of city-states under Athens against the Peloponnesian League under Sparta. Their rivalry had its roots in the early 5th century bc wars with Mediterranean rival Persia.

Persian King Cyrus the Great had conquered the coastal city-states of Ionia (on the present-day Anatolian Peninsula of Turkey) in 547 bc, ruling them through despotic local satraps. In 499 bc one of the Ionian tyrants led an ultimately unsuccessful revolt against Persian rule with primary support from Athens. Seven years later Persia’s King Darius I led a punitive expedition against Greece, specifically targeting the rebellious city-states of Athens and Sparta, each of which had executed Persian envoys sent to demand their submission. In 490 bc the Athenians won their stunning victory over superior Persian forces at Marathon.

Ten years later Darius’ son and successor Xerxes I launched a second invasion of Greece. The Greek city-states largely banded together to defeat the Persians, but in the wake of their victory Spartan general Pausanias betrayed sympathies for Persia, releasing prisoners with personal ties to Xerxes and offering to deliver the city-states into Persian hands in exchange for the hand of Xerxes’ daughter. His treason alienated many of the allied city-states, and Sparta was reluctant to continue what it saw as an unwinnable war against Persia. It withdrew from the alliance and reformed its regional Peloponnesian League, while many of the other city-states coalesced around Athens, forming the Delian League. Over the following decades Athens went on the offensive against Persia and solidified its hold on the Aegean, while Sparta withdrew further into the Peloponnese. The onetime Greek alliance broke down into a standoff between mutually suspicious and increasingly hostile leagues. “The growth of the power of Athens,” wrote Greek historian Thucydides, “and the alarm which this inspired in [Sparta], made war inevitable.”

The Peloponnesian War opened as Athens and Sparta sought to shore up their respective leagues and woo neutral city-states to their cause. A tenuous peace lasted until 431 bc, when Athens intervened in a clash between Spartan-allied Corinth and Megara, breaking the terms of the peace and prompting Sparta to rally its member states into conflict with Athens. Spartan strategy focused on occupation of the land surrounding Athens followed by a siege of the city, while Athenian strategy relied on its dominance of the sea routes. Initially, neither could gain the upper hand. It was an ostensible Athenian ally that planted the seed for a change in Spartan tactics.

At the Olympiad of 428 bc ambassadors from Mytilene, which hoped to wrest control of its home island of Lesbos in the northeastern Aegean, sought help from Sparta and Boeotia in its planned revolt against Athens. The Mytileneans urged the Spartans to choke off Athens at the source of her strength—that is, the Hellespont (present-day Dardanelles), its supply route for Crimean grain. Athens put down the revolt before the admittedly reluctant Spartans could send support, but Sparta filed away the advice regarding the Hellespont. In the meantime, after a decade of costly seesaw battles, the beleaguered leagues signed another tentative peace in 421 bc that, aside from minor probing battles, lasted some six years.

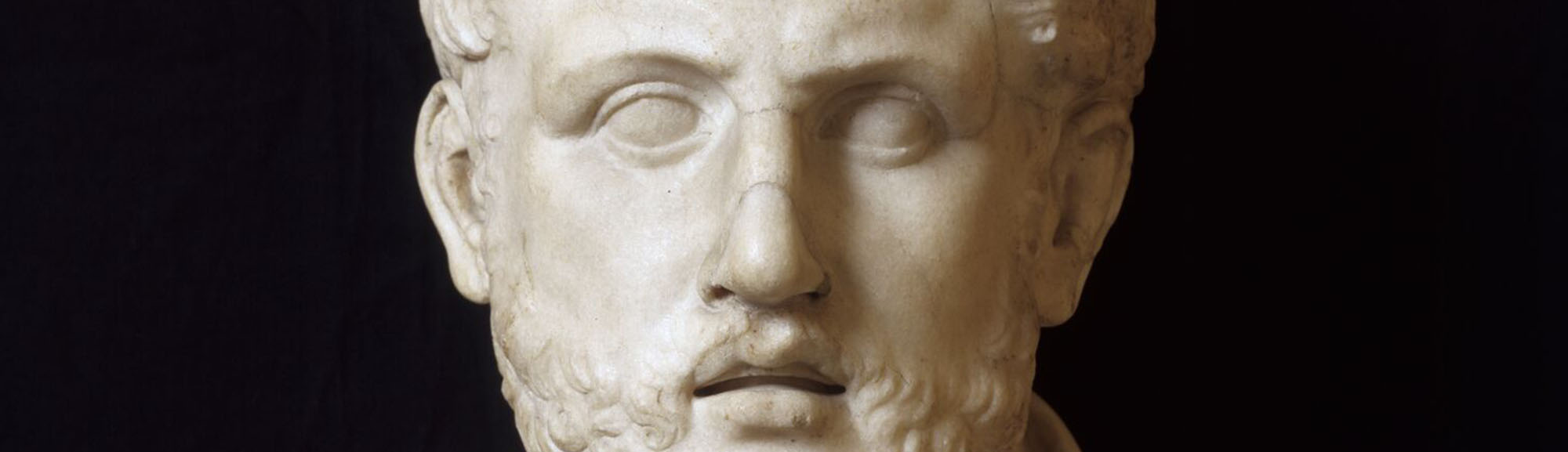

Athens faced perhaps a greater threat from fractures within its aristocratic ruling class, divisions that flared up in 415 bc at the outset of a campaign against Spartan-allied Syracuse and its allies on Sicily. The leading voices were the elder dovish Nicias, who had brokered the latest peace with Sparta, and the younger hawkish Alcibiades, who pointed to Athens’ past supremacy in his appeal for an expedition to Sicily. Alcibiades proved more persuasive before the Athenian Assembly.

On the eve of the campaign, however, someone mutilated statues of Hermes, messenger of the gods, throughout Athens. Alcibiades’ political opponents accused him of the vandalism and of profaning the sacred rites of the Eleusinian Mysteries. Alcibiades demanded an immediate trial, but his opponents shrewdly argued for a postponement, then sought to have him arrested on arrival in Sicily. Alcibiades slipped their noose but was convicted in absentia, condemned and stripped of all property. A man without a country, he defected to Sparta and watched the Sicilian campaign unfold. When his former men-at-arms moved on Messina, expecting internal allies to hand over the city-state, Alcibiades warned the Syracusans and prevented its capture. Sparta thwarted an initial Athenian siege of Syracuse, while the overcautious Nicias threw away a second abortive siege in 413 bc, surrendered his invasion force and was summarily executed.

Alcibiades, meanwhile, advised the Spartans to put the Athenians on the defensive by maintaining a year-round base at Decelea in Attica, within sight of Athens’ walls. In a show of force the Spartans then sent him with a fleet to Anatolia, where he persuaded Tissaphernes, the Persian satrap of Lydia and Caria, to financially support the Peloponnesian League and encouraged several Ionian city-states to rebel. So close to the Hellespont, the Persian-funded fleet constituted a terrible threat, and Athens reacted swiftly, sending its own fleet to bring Chios and other city-states back into alignment.

Even as he shored up political relations with his new Spartan allies, Alcibiades’ passions collided with his ambitions. The decisive split came in 412 bc when Timaea, wife of Spartan King Agis II, gave birth to a son who looked suspiciously like the young Athenian commander—enough to prompt Agis to order the latter’s assassination. Finding himself once more on the run, Alcibiades sought refuge in Tissaphernes’ court. There the silver-tongued, two-time traitor soon convinced the satrap that the continued depletion of both Greek factions was in Persia’s interest. The equally ambitious and self-serving Tissaphernes promptly withdrew his support of the Spartan fleet by refusing to reinforce it and canceling a promised pay increase to Peloponnesian crewmen.

Meanwhile, in Athens, playing on general discontent with the course of the war, ambitious aristocrats had seized power, rewriting the constitution and replacing the democratic parliament with an oligarchy of 400 chosen elites. To sway the populace into compliance, the oligarchs then pledged to appoint a broader oligarchy of 5,000 Athenian citizens—in fact chosen from among their fellow aristocrats.

If they were to succeed, the oligarchs also had to secure the support of the Athenian army and fleet on Samos in the north Aegean. Not by coincidence, Alcibiades—who by then envisioned a glorious return to favor in Athens—was already in contact with the commanders on Samos when debate arose over whether to support the oligarchy. Seeing an even greater prize in reach, he curried favor with generals Thrasybullus and Thrasyllus, who had resolved to adhere to the ideal of Athenian democracy while continuing the fight against Sparta, independent of the oligarchy in Athens. Alcibiades, with empty promises of Tissaphernes’ materiel support, convinced the troops on Samos to reinstate him as a general.

The main Athenian fleet, under Thrasybullus and Thrasyllus, then sailed north to confront the Spartans in the Hellespont. In 411 bc the Greeks prevailed at Abydos, thanks to timely reinforcement by a force of 18 triremes under Alcibiades. When the Spartans complained to Tissaphernes regarding the satrap’s lack of support, he made a show of having Alcibiades imprisoned, though the Athenian commander soon “escaped.” In the absence of the promised Persian support, the Athenians were forced to regroup, and the Spartans soon took the Hellespont port of Cyzicus. Despite his loss of face Alcibiades managed to hang on to his command, and in 410 bc he earned redemption by helping to annihilate the Peloponnesian fleet at Cyzicus and retake the city, killing the Spartan admiral, Mindarus, in the bargain. Alcibiades followed up that victory in 408 bc with his participation in the successful siege of Byzantium (present-day Istanbul). The Hellespont was again under Athenian control.

With that string of victories under his belt Alcibiades finally sailed to the Athenian port of Piraeus in 407 bc. Citizens gave the once disgraced general a hero’s welcome, and the reinstated democratic Assembly also rallied around him, restoring his property and proclaiming him strategos autokrator, supreme commander of all land and sea forces.

Alcibiades’ long-standing dream of becoming the parliamentary dictator of Athens looked within reach. But his erstwhile allies, Sparta and Persia, were on the move.

In 407 bc, as Alcibiades basked in glory in Athens, Sparta appointed the seasoned veteran Lysander admiral of its fleet, while Cyrus the Younger, a son of Persian King Darius II, was named satrap of Lydia. Cyrus favored the Spartans, as he envisioned using their infantry in his future plans to seize the throne of Persia from his brother Artaxerxes II. With Cyrus’ money Lysander raised a new fleet at Ephesus, lured away many of the Athenians’ best helmsmen and sailed out to meet and defeat Alcibiades’ waiting fleet at Notium. Alcibiades had neglectfully left the fleet in command of his helmsman, and the strategos autokrator’s enemies wasted no time in stripping him of his title and ousting him permanently from favor. The Athenians replaced him with an experienced commander named Conon.

In Lysander he faced a formidable adversary. Determined to win, the Spartan admiral understood what statesmen back home could not—that Persia kept a hand in the war only to maintain its bridgeheads in the Aegean and the Hellespont. Thus, like Cyrus, he maintained the diplomatic façade as long as it served Sparta’s purposes. Yet despite his obvious fitness for command, Lysander, too, soon lost his position, as Spartan law forbade an admiral from serving more than a year. Thus in 406 bc Callicratidas took his place as commander of the Spartan fleet. He was a poor choice.

A Spartan traditionalist, he was loath to seek support from the “barbarian” Cyrus and soon alienated the Persian satrap. More diplomat than commander, Callicratidas preferred to re-establish peace with Athens and was correspondingly reluctant to seek out and destroy its fleet. Instead he moved to secure Lesbos and thus reapply pressure on the Athenian supply lines. That spring he took the coastal city-state of Methymna and sent the disembarked Spartan army marching on the capital of Mytilene. He then led his fleet of 170 galleys against Conon, who had arrived off Lesbos with 70 galleys and anchored amid the Hekatonisa, or Hundred Islands (the present-day Ayvalik Islands of Turkey). Conon initially sought to outmaneuver and attack the superior Spartan fleet, but he lost 30 vessels in the attempt and was soon trapped in the port of Mytilene with his remaining 40 ships. Blockaded by sea and besieged by land, Conon dispatched two messenger galleys, one of which made it through the Spartan encirclement and three days later arrived at Piraeus. Though strapped for resources, the Athenian Assembly reacted immediately, melting down sacred statues into coins to fund the construction of a relief fleet and extending citizenship to foreign sailors and freed slaves needed to man the dozens of new ships.

Within weeks a fleet of 110 triremes set sail for Samos, where they joined 10 Athenian galleys and 30 allied ships. The combined fleet soon arrived at the Arginusae (the present-day Garip Islands off Turkey’s Dikili Peninsula), 9 miles southeast of Cape Malea on Lesbos. Athens had placed the relief fleet under the joint command of eight generals, each with his own approach. Seeking to immediately relieve Conon, one commander had rushed toward Mytilene with his division, only to come under attack in the channel and lose 10 of his dozen ships. Callicratidas, meanwhile, had learned of the Athenians’ approach. Leaving 50 galleys under the command of Eteonicus to pin Conon in place, he deployed his fleet off Cape Malea facing the Arginusae. Spotting fires ashore, he surmised the Athenians had disembarked, thus he decided to launch a surprise attack. Bad weather stayed his hand until morning.

At dawn the respective fleets advanced on one another across the channel between Lesbos and the Arginusae.

The Athenian fleet approached with 90 ships in its first line, and 30 ships on each flank in a second line. The first line comprised the divisions of Aristocrates, Diomedon, Protomachus and Thrasyllus, the 10 galleys from Samos and the allied galleys with the flagships. Backing them on the left were Pericles and Erasinides, on the right Lysias and Aristogenes. Should the faster Spartan ships attempt to maneuver between vessels in the first line, triremes from the second line would move up to intercept them.

Callicratidas, indeed intending to break through the Athenian formation, had arranged his fleet in a single line. The master of his ship, Hermon the Megarian, noting the Athenian fleet outnumbered them, advised Callicratidas to withdraw. “Sparta would fare none the worse if I am killed,” the commander replied, “but flight would be a disgrace.” Splitting his fleet in two to avoid being flanked, he led the right in a direct attack. Among the first ships to close on the enemy fleet, Callicratidas’ flagship targeted Pericles’ trireme for ramming. The impact, however, tossed the hapless Spartan commander overboard to be swallowed up in the waves. The leaderless right collapsed, soon followed by the Spartan left. Seventy Spartan ships and their crews followed their commander to the bottom, while the survivors fled to Chios and other Spartan ports.

A messenger ship made it back to Mytilene and delivered the bad news to Eteonicus. Seeking to quell the hopes of the blockaded Athenians and avoid a panic among his own men, he ordered the crew of the messenger ship to immediately sail for Chios, while he reported a glorious Spartan victory.

Though they lost 25 ships, the Athenians were determined to exploit their victory and smash Eteonicus’ blockading fleet. However, a storm came up, thwarting their plans and preventing a smaller fleet under captains Theramenes and Thrasyboulos from recovering Athenian survivors and the dead. Eteonicus took advantage of the reprieve to break port. After calmly ordering his crews to have dinner, he instructed them to sail to Chios with all speed. Eteonicus himself went ashore, ordered the Spartan camp stricken and burned, and led the infantry back to the waiting galleys in Methymna. Conon fell for the ploy. When he finally did emerge with his ships, he found only Athenian galleys sailing to his aid.

The naval battle off the Arginusae had pitted nearly 300 ships and some 60,000 marines against one another in rough seas. But what should have been held up as a crowning victory for the Athenian navy dissolved into public outcry when citizens learned of the failed recovery of some 4,000 crewmen from the 25 lost triremes.

In no mood to celebrate, the Athenians instead deposed all the generals but Conon. Forewarned of the ill winds blowing from Athens, Protomachus and Aristogenes stayed away from the capital. The other six—Aristocrates, Diomedon, Erasinides, Lysias, Pericles and Thrasyllus—returned home to a storm of official censure. First to face the music was Erasinides, who was charged with misconduct. When a court threw him in prison, the other generals made a statement before the Senate, outlining the course of the battle and explaining the severity of the storm off the Arginusae. Unconvinced, the senators also ordered them imprisoned and turned over to the Assembly for trial.

At the trial Theramenes—co-captain of the fleet that had failed to recover the crews of the stricken galleys—appeared as the main accuser, seeking to deflect attention from himself and instead finger the generals. Boldly accusing them of failing to take responsibility, he presented a letter they had written to the Senate and Assembly in which they fixed blame on the storm alone. Though denied a full hearing as prescribed by law, the generals spoke briefly and persuasively in their own defense. Despite the charge levied by Theram-

enes, they refused to blame him or his co-captain Thrasybulus, but reiterated their claim the storm alone had thwarted recovery efforts. Other captains and crewmen echoed their claims, testifying to the severity of the storm.

The generals were on the verge of convincing the Assembly of their innocence when nature intervened. Dusk had fallen, and as it would have been impossible to count hands, the assemblymen agreed to postpone the decision for another day. They further agreed to have the Senate draft a proposal on how to decide the generals’ fate.

In the meantime Athenians celebrated the annual Apaturia, a three-day Ionian festival during which clans came together to feast, worship, discuss general affairs and register newborns. Theramenes and supporters took advantage of the gathering to persuade kinsmen to appear before the Senate in mourning clothes, claiming to be relatives of the missing, and they bribed Senator Callixeinus to draft a proposal favorable to their desired outcome. Callixeinus resolved to poll the tribes, presenting each with two urns—one to collect votes to convict, the other votes to acquit. Further stacking the deck, the accusers brought forward a man who claimed to have survived the battle by floating atop a flour barrel. The man insisted his drowning countrymen had begged him to bring charges against the generals who had left them to die.

Bucking the push to convict, Euryptolemos, an assembly-man and member of a leading Athenian family, questioned the constitutionality of Callixeinus’ proposal—namely to judge the generals together, instead of separately. Others supported his motion, but they backed down when the mob gathered to witness the proceeding shouted down the dissenters and threatened to judge them in a similar vote.

When still other assemblymen refused to put the proposal to a vote, Callixeinus took the floor to repeat his charge, and the mob called for the impeachment of anyone who objected. Only then did the cowed assemblymen agree to put it to a vote. Socrates, the sole dissenter, declared he would do only what the law provided for and not what the mob required. Euryptolemos then rose once more to make a long and impassioned plea on behalf of the generals for a full, fair and above all constitutional defense.

Following his oration he countered Callixeinus’ proposal with a resolution to try the generals separately. The assemblymen voted to adopt Euryptolemos’ proposal. But on a technical objection they called for a second vote, which adopted Callixeinus’ proposal to judge them together. When the urns were collected and the tribal votes tallied, the Assembly found the scapegoat generals guilty, confiscated their property and condemned the six to death.

As they were about to be led off to public execution, Diomedon took the floor amid resounding silence to address the Assembly and onlookers: “Men of Athens, may the decision taken concerning us turn out auspiciously for the city. Regarding the vows we made for victory: Since Fortune has prevented our discharging them—and it would be well that you give thought to them—pay them to Zeus the Savior and Apollo and the Furies, since it was to them we made our vows before we won our victory at sea.”

Thus did Athenians reverse the result of their generals’ victory off the Arginusae. For while their demoralized fleet passed largely into the hands of lesser commanders, Spartans broke with convention to rename Lysander as their admiral. In 405 bc he finally and utterly destroyed the Athenian fleet at Aegospotami on the Hellespont, forever changing the balance of power in Greece.

The regretful Athenians later denounced those who had instigated the proceedings against the condemned generals, imprisoning Callixeinus and four others. But following the loss at Aegospotami and a subsequent insurrection, the five hated men escaped. Years later Callixeinus returned to Athens, but no one would speak to him, let alone bother with a retrial. Alone and forgotten, he died of starvation.

Thomas Zacharis is based in Thessaloniki, Greece. For further reading he recommends The History of the Peloponnesian War, by Thucydides, and Hellenica, by Xenophon.

First published in Military History Magazine’s March 2017 issue.