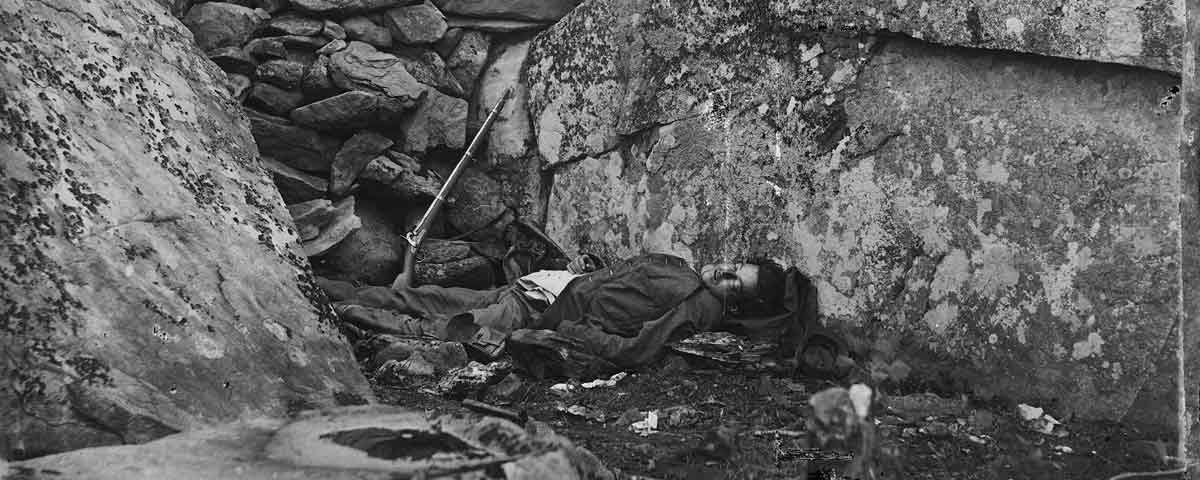

A Confederate soldier, his youthful face turned toward the viewer, lies behind a stone wall built between two boulders in Gettysburg’s notorious Devil’s Den. His head rests on a knapsack, and his rumpled uniform coat makes it almost appear as if he is asleep under a blanket. But relics of war intrude on the scene so there is no mistaking he is a casualty of ferocious combat. A musket leans against the wall in the background, and an open cartridge box lies at his side. A cap is next to his head, where it landed after the soldier fell dead. Photographer Alexander Gardner took the arresting image on July 6, 1863, and when he published it for public consumption, he titled it “Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter” to convey that the soldier was a marksman who had been picking off Union soldiers on Little Round Top, seen in the distance, before a shell fragment fired by a Union cannon snuffed out his life.

An overarching question about the image had long intrigued me: Just who was the unfortunate Confederate casualty? The desire to answer that set me on a research quest to find a name, and I am confident I have been successful. But first a bit of history on the image with one of the most intriguing Civil War photography backstories.

Gardner and his assistant, Timothy O’Sullivan, actually staged that dramatic scene by moving the dead soldier, who was not a sharpshooter but a common foot soldier, from another location in Devil’s Den to the barricade to create a dramatic tableaux, complete with carefully dressed accessories that included the musket, accoutrements, and uniform items. Gardner and Sullivan took two plates of the Confederate at the wall, one of which was a stereoview. The fact that the corpse was photographed in two separate locations went unnoticed for nearly a century until Frederick Ray, an illustrator for Civil War Times, wrote the short article, “The Case of the Rearranged Corpse” in the October 1961 issue of this magazine.

In 1975, photographic historian William Frassanito published his groundbreaking book on Gettysburg photographs titled Gettysburg: A Journey in Time. In his study of the “sharpshooter” photographs, Frassanito identified the body in its first location and estimated the body was moved 40 yards (later revised to 72 yards) to the stone barricade. And now, the story of the image continues, with the great possibility that the soldier in the image has been identified.

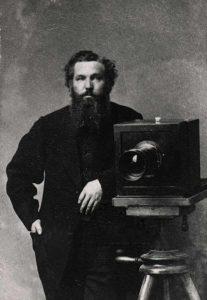

Before that hypothesis is explained, a bit of background on Gardner and the battle situation at Devil’s Den will be helpful. When the war began, Gardner had been managing Mathew Brady’s Washington, D.C., gallery. In September 1862, Brady assigned Gardner to take images of the aftermath of the Battle of Antietam. Those images of battlefield dead shocked the nation, but Brady got the fame, not Gardner. That prompted Gardner to leave Brady, and in the spring of 1863, he opened his own gallery in Washington with his brother James. He also took with him photographers O’Sullivan, James Gibson, William Pywell, David Knox, John Reekie, and W. Morris Smith.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]It is one of the Civil War’s most iconic, poignant photographs.[/quote]

Soon, Gardner and a few of his photographers were following the Army of the Potomac in June as it chased the Army of Northern Virginia’s movement toward the Potomac River. Gardner’s exact whereabouts in the days leading up to the battle are murky, but it is clear that Gardner arrived on the battlefield late on the afternoon of July 5, possibly after he had stopped in Emmitsburg, Md., on July 4 to check on the welfare of his son attending a boarding school there. And it is possible he may have sent the rest of his photographic team on to Gettysburg that day.

Historians only have a general idea of the travels of Gardner’s team during their time at Gettysburg, but it is certain that during the morning to early afternoon on July 6, they were busy photographing scenes on the Trostle and Rose farms on the southern portion of the battlefield. A Union officer in the 17th Maine, Charles Mattocks, witnessed the photographers at work and wrote in his journal on July 6 that, “Photographic artists have been busy in taking views upon the battlefield. Groups of the dead, graves, dead horses, and in fact almost everything forms the base of their operations.”

Then the photographers most likely made their way to the Devil’s Den area when they happened upon the fallen Confederate soldier in an open space on the west side of the rock formation, near what is now known as the “Triangular Field.” The youthful appearance and relatively good condition of the body may have piqued their interest enough to spend extra time on this particular soldier. They expended six exposures on him, including three stereoviews at various angles and a large format photograph at the downhill location.

At the sharpshooter’s position Gardner took one stereo format photo and one large view version. It is unknown who came up with the notion to move the body, but perhaps Gardner was eager to make a name for himself and move out from under the shadow of Brady, his former mentor.

Brady would also travel to Gettysburg, but he began taking images around July 15, after the bodies had been interred in their hasty graves. The public expected another death series from Brady, so he took some of his own artistic license. In several photographs, Brady had posed an assistant as a dead soldier. And even though those portrayals were rather unconvincing, and although Gardner had truly captured the horrors of the three-day battle, Brady’s Gettysburg views again received most of the recognition.

In August 1863, Brady’s photographs appeared in Harper’s Weekly, a nationally circulated newspaper, in the form of woodcuts. The next month, Gardner released his Incidents of the War catalog that contained all his Gettysburg views. But it was not until 1865, after the end of the conflict, that Gardner’s Gettysburg views appeared as woodcuts in Harper’s Weekly. A montage of several of Gardner’s photos included the “sharpshooter” photographs, titled “A Sharpshooter’s Last Sleep.” The image of the dead Confederate at the barricade also appeared in Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War that was published that same year, 1865.

I knew it would be a daunting task to identify the dead soldier, and the probability that I would find the answer was extremely low, but I kept on through the twists and turns of my investigation. The results, it turned out, surpassed my expectations and were more than I could have hoped for. I first set out to investigate some notions that are still prevalent today. Shockingly, some people believe that the “sharpshooter” was a live person posing as a dead soldier, just as Brady had used his assistant for a few of his views. As is clear from the detail of the soldier’s face, however, one eye remains slightly open, his face had swollen, and hands had shriveled up, all indications of the onset of decomposition.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]In September 1862, Brady assigned Gardner to take images of the aftermath of the Battle of Antietam. Those images of battlefield dead shocked the nation, but Brady got the fame, not Gardner. Perhaps Gardner was eager to make a name for himself and move out from Brady’s shadow.[/quote]

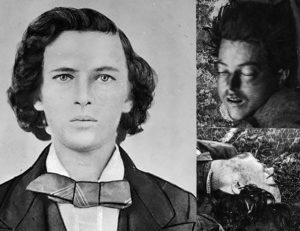

I then looked into some of the identifications attributed to the soldier in the past and focused in on one intriguing possibility. In 1911, family members claimed that the soldier was Andrew Hoge, who died at the Battle of Gettysburg. His story appeared in Confederate Veteran magazine in 1925. The story of Hoge’s death seemed plausible and even contained a detail not known to the general public. Gardner had inexplicably mentioned a canteen in his rough draft of the narrative for the photograph even though there was no canteen visible in any of the six photographs (the detail never made it into the final draft of Gardner’s Sketch Book).

But Hoge’s cousin was present when he died and wrote that he had closed his eyes and placed a canteen between his elbow and his body before he left him. After digging further, I found that an early photograph of Hoge shows a similar facial likeness to the sharpshooter. I can see why Hoge’s family members could have thought the soldier was their relative and why they would have rationalized him being in Devil’s Den. There is one glaring problem with this theory: Hoge and his cousin were both members of the 4th Virginia Infantry, and as Frassanito pointed out in another of his books, Early Photography at Gettysburg, that regiment was nowhere near Devil’s Den during or after the battle. I had to resume my search.

In 2014, John Heiser, a historian at Gettysburg National Military Park, wrote a series of articles on the photo for the park’s blog, From the Fields of Gettysburg. He surmised that the casualty was a Georgian because Brig. Gen. Henry L. Benning’s 2nd, 5th, 17th, and 20th Georgia infantry occupied both locations throughout the day and into the evening of July 3 where the dead Confederate was photographed.

Heavy skirmishing began in the Devil’s Den vicinity late in the afternoon on July 3, after the repulse of Pickett’s Charge. Emboldened Pennsylvania regiments of Colonel William McCandless’ brigade pushed toward the rock formation about 5:30 or 6 p.m., eager to take back ground lost by the Union on July 2. McCandless’ men began turning Benning’s left flank, forcing the Confederate commander to withdraw his regiments from Devil’s Den to the west under heavy fire.

Heiser was leaning toward the idea that the soldier was a member of the 15th Georgia because that regiment served as the brigade’s rear guard as their fellow Georgia regiments retreated toward the Emmitsburg Road, and I agreed with that. But, although the 15th lost more than 100 men at Gettysburg, I found only three reported as being killed in action on July 3. Two were mortally wounded and had been buried miles away from Devil’s Den. The remaining soldier was Everard Culver, who was just 19 years old when he was killed.

Everard had four brothers in the regiment, and Edgeworth Bird, a member of the 15th, wrote home that they were “very distressed that poor Ev’s body could not be recovered from the hands of the enemy for burial.” Because of the age of Culver and that his body was left on the field, this possibility required further investigation. I could not find a photograph of Everard, but I managed to find one of his brother who bore little resemblance to the “sharpshooter,” and my suspicion that Everard was the soldier in the photograph began to diminish.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Just who was the unfortunate Confederate casualty?[/quote]

My search of the 17th Georgia’s casualties yielded no candidates, and I turned my attention to the 2nd and 20th Georgia, but I could find no soldiers who were killed in action on that date. It was disheartening, and I feared that incomplete Confederate records may have stalled my investigation, but I continued my search and finally got the break I needed.

I found the accounts of two soldiers from the 2nd Georgia Infantry: William Houghton’s Two Boys in the Civil War and After and copies of John Bowden’s papers in the Gettysburg battlefield library. Houghton, who served in Company G of the 2nd, had mentioned that when they received orders to withdraw, they formed up again about where Gardner may have taken his first image of the body. The other soldier, Bowden from the 2nd’s Company B, wrote that a soldier was killed crossing the “danger point” where the regiment was exposed to Union fire during their withdrawal.

I finally found a soldier listed in Robert K. Krick and Chris L. Ferguson’s book, Gettysburg’s Confederate Dead: An Honor Roll From America’s Greatest Battle, who was killed in action late in the afternoon or the early evening of July 3, when Benning’s Brigade was driven from Devil’s Den. His name was John Rutherford Ash of Company A of the 2nd Georgia.

Private Ash was only 25 years old when he died at Gettysburg, and his body was never recovered. Ash was born in 1837, and by searching the Find a Grave website, I found that a memorial stone, not a gravestone, had been erected for him in the Hebron Presbyterian Cemetery in Banks County, Ga., along with another one for his younger brother who was killed at Vicksburg in April 1863. The date of death on John’s stone is July 4, but it is reasonable to believe that the information about his death came from a comrade, and I recalled that John Bowden had mistaken the regiment’s withdrawal date as July 4 in his account.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Ash and the dead soldier shared the same exact facial features…the likeness was haunting[/quote]

My good luck persisted when I found a crisp 1850s photograph of John Ash at the Georgia Department of Archives and History, and I stared at it on my computer screen in disbelief. Ash and the dead soldier at the barricade shared the same exact facial features, including their ears, nose, chin, lips, and eyebrows. The likeness was haunting. I also realized that if Ash was killed on July 3, it would help explain why his body was not as decomposed as others photographed by Gardner. It would be reasonable to believe that John Ash and the Devil’s Den casualty photographed by Gardner are one and the same, even if absolute proof may forever remain elusive.

I am hopeful, however, that in the future, more information will come to light to help confirm the identification one way or the other. Gardner’s actions in staging the photograph on July 6, 1863, were morally wrong and unethical by our standards, but he clearly explained the intent of his photograph in his Sketch Book: “Such a picture conveys a useful moral: It shows the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry. Here are the dreadful details! Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation.”

Scott Fink, an Army veteran who received the Purple Heart for injuries sustained in Iraq, frequently travels to Gettysburg from his home in Olney, Md. His forthcoming book, Photo History: Gettysburg, will delve into great detail about the “sharpshooter” image as well as other photographs.

A Moving Controversy

In 1998, a new theory emerged about the “sharpshooter” photographs when James Groves, a Maryland artist, produced an online study of the images titled The Devil’s Den Sharpshooter Re-Discovered, in which he concluded that the photographs at the barricade were taken first and then the body was moved for additional images in the vicinity. The premise of his study was based on an account by Union artillery Captain Augustus P. Martin, who was stationed on Little Round Top. Martin claimed that just after the battle he saw a “dead Confederate lying upon his back behind a stone wall” who had been killed by a Federal artillery fire. Martin explained the dead Rebel had been an actual sharpshooter, whose accurate shooting had drawn Union shellfire. Martin’s telling seemed to establish the Rebel had died at the stone wall, and was then moved farther downhill, thereby validating Groves’ speculation.

Captain Martin’s story first appeared in the Gettysburg Compiler in 1899, and he was very likely aware of Gardner’s photograph and “sharpshooter” caption. Also in 1867, local Gettysburg photographers had taken photos at the barricade, and their caption indicates they were aware of Gardner’s photograph. Furthermore, photographer William Tipton had reprinted Gardner’s image around the time of Martin’s 1899 article. Therefore, Gardner’s published story about the image was well known by 1899, and it is plausible that Martin molded his account to mesh with Gardner’s.

Some of Groves’ key points have been disproved, while others have maintained their merit. Nothing, however has convinced me the soldier was a specialized sharpshooter. As I continue to study Gardner’s Gettysburg photography, I agree with Frassanito’s theory that the soldier was dragged to the barricade to compose an absorbing image. While I may disagree with Groves’ conclusions, I do applaud his effort to challenge perceptions of the famous photograph.–S.F.