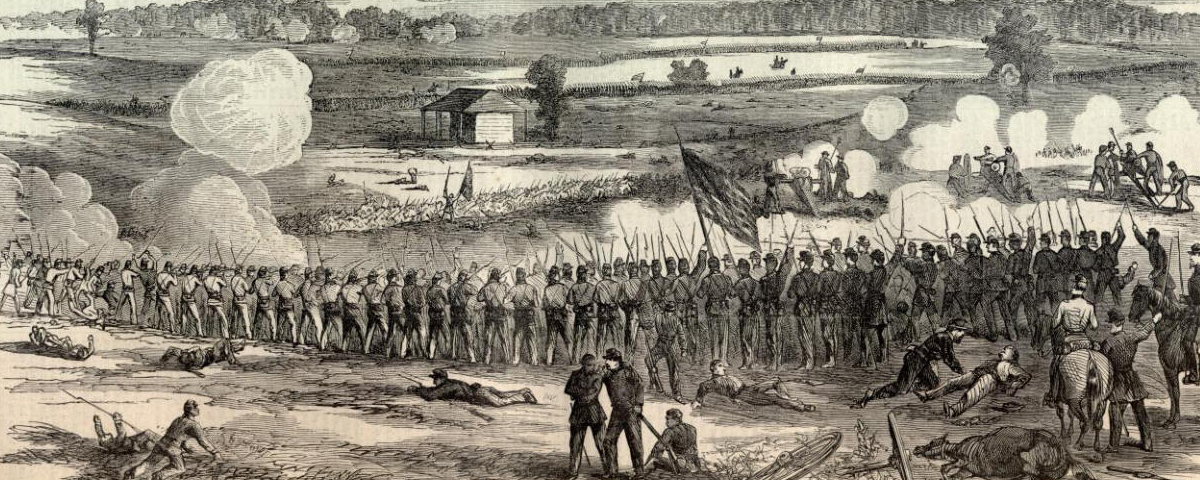

Account of the Battle Of Perryville, a western theater Civil War Battle during the American Civil War

Battle Of Perryville Summary

Location

Perryville, Boyle County, Kentucky

Dates

October 8, 1862

Generals

Union: Don Carlos Buell

Confederate: Braxton Bragg

Soldiers Engaged

Union Army: 22,000

Confederate Army: 16,000

Outcome

Inconclusive

Casualties

Union: 4,200

Confederate: 3,400

Ripping volleys of rifle fire and the shattering boom of cannons rolled over the hillsides as members of the 21st Wisconsin Infantry Regiment filed into a cornfield between two Federal positions. The troops, nervously clutching their Austrian muskets, had been in the service for less than a month. Many of them had never before fired their rifles, and the unit was so green that they carried no regimental banner. Amid the stalks was 18-year-old Christian Weinman, of Company I. Weinman and his comrades had taken part in only a handful of drills, but momentarily these soldiers would experience a horrific baptism of fire at Perryville in Kentucky’s largest Civil War battle. Suddenly Confederate battle flags unfurled above the corn and enemy bullets ripped into the field, cutting stalks and dropping soldiers. Outflanked, the regiment stampeded to the rear. One of those left lying in the dust was young Christian Weinman.

More than a month later, Weinman’s sweetheart received a crushing letter from Thomas Allen, a soldier in the 21st. ‘It is with great sorrow I write to inform you of the death of Christian Wineman [sic], Allen wrote. He died at hospital No. 1 Springfield Washington County Kentucky on the 9 of Nov. he was shot through the side at the battle of perry vale and we all thought that he was getting better but he began to be worse and he was out of his mind…members of the church got him a good coffin and he was buried in the church yard and then got him a good cross made and lettered…so that will be one consolation to know that he is buried as he ought to be….

The 21st Wisconsin lost a third of its command at Perryville. Charles Carr of Company D wrote of the battle, No pen nor no tongue can begin to tell the misery that I have seen.

The 21st Wisconsin was organized in July and August 1862 and mustered into service in Oshkosh on September 5. The soldiers likely knew that they would not have to wait long for action. That summer, Confederate General Braxton Bragg and Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith invaded Kentucky to draw Union Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio away from Chattanooga, an important railroad hub. Furthermore, the Confederates hoped thousands of Kentuckians would rally to the Southern banner.Smith struck first, entering the commonwealth through the Cumberland Gap. Smith’s Army of Kentucky then rapidly moved northward, decimating an inexperienced Federal force at Richmond and then capturing Lexington and the capital city of Frankfort.

Braxton Bragg marched his Army of the Mississippi into Kentucky near Glasgow, then besieged a Union garrison at Munfordville, which gave Buell the opportunity to slip out of Nashville and race to Louisville. Thousands of Confederates were swarming throughout central Kentucky, and the Wisconsin troops knew that a fight was imminent.

Commanded by Colonel Benjamin Sweet, the regiment went to Covington, where they occupied trenches protecting Cincinnati. The 21st arrived in Louisville by September 15, 1862, and helped fortify the town against the Southern armies slowly creeping toward it. On September 25, Buell’s legions marched into the city. The haggard and dirty veterans of Buell’s army shocked many of the new recruits. Mead Holmes of the 21st Wisconsin called Buell’s exhausted troops such jaded men!

Buell quickly reorganized the Army of the Ohio and placed the 21st Wisconsin in Colonel John C. Starkweather’s 28th Brigade of Brig. Gen. Lovell H. Rousseau’s division of Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook’s 1st Corps. The brigade included three other infantry regiments, the 24th Illinois, 79th Pennsylvania and 1st Wisconsin. Two artillery batteries — the 4th Indiana Light Artillery, commanded by Captain Asahel Bush, and Battery A of the Kentucky Light Artillery, led by Captain David Stone — were also attached to Starkweather’s command. The brigade numbered approximately 2,500 men.

Buell prepared to drive the Confederates from Kentucky. Knowing that Smith’s command was near Frankfort, Buell sent more than 18,000 Union troops toward the capital as a diversion. The majority of his command, numbering nearly 58,000 men, barreled toward Bardstown and Bragg’s forces. The 21st Wisconsin joined the advance on Bardstown.

The troops suffered from a severe drought that plagued central Kentucky. As most streams, creeks and wells were completely dry, the soldiers drank from stagnant, fetid ponds. Mead Holmes recalled that men shared the water with wallowing hogs. He remarked that many times when he finished drinking, A deep sediment remains in the bottom of the cup. As the campaign continued, soldiers suffered from dysentery, typhoid and other ailments.

To take advantage of an adequate water supply and extensive road network, Bragg’s Confederates withdrew to Perryville when Buell’s soldiers converged upon Bardstown. The Union army doggedly continued the march to Perryville in the heat and dust of that drought-stricken October.

Rousseau’s division left Mackville, 10 miles north of Perryville, early on the morning of October 8. Colonel Sweet was ill and rode in an ambulance, so Major Frederick Shumacher assumed command of the regiment. As they neared Perryville, the faint rumble of cannon fire crackled in the distance, which the inexperienced troops thought was distant thunder. A spattering of musketry could also be heard as they moved down the Mackville Road. The regiment was marching into battle.Starkweather’s brigade arrived on the battlefield at 1:30 p.m. Major General McCook’s rookie 1st Corps was strung out in battle lines two miles north of Perryville. Earlier, these troops had seen immense clouds of dust rising from the town, and Union officers mistakenly believed that the Confederates were retreating. Therefore, McCook’s corps was surprised when Bragg’s 18,000 Southerners attacked. As Starkweather’s regiments filed into position, the lead Confederate brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Daniel S. Donelson, moved against the northern end of McCook’s line.

With Union artillery pounding Donelson’s advance, Starkweather formed his troops to face the enemy’s right flank. He placed most of his command on a narrow ridge 300 yards behind the Union left flank, where a brigade of green troops commanded by Brig. Gen. William R. Terrill anchored the northern end of McCook’s line. Immediately at the base of the ridge was the Benton Road, which curled around the southern end of the hill. On the crest of the steep ridge (today known as Starkweather’s Hill), Colonel Starkweather placed his two artillery batteries. Bush’s guns held the left, while Stone’s Kentucky battery anchored the right. The 12 guns were crammed on the narrow hill with their wheels nearly touching.

The 21st was the last of Starkweather’s brigade to arrive on the field. Reaching Starkweather’s position, the men were told to enter a cornfield located in a ravine on the east side of the Benton Road. While Starkweather gave the order,it appeared that his division commander, Rousseau, had made the decision to place the Wisconsin troops in the cornfield, between two groups of Union soldiers. Terrill’s brigade, on a hill to the front, fired at the advancing Confederates. Behind the Wisconsin troops, Starkweather’s other regiments held the ridge. Members of the regiment later condemned their commanders for ordering them into this ravine between the two hills. It was a deadly decision. Since several hundred of the inexperienced troops had dropped out during the long, hot march, and also due to the fact that Companies B and C were in the rear guarding the ammunition train, the exhausted regiment numbered 400-500 men.

Intense gunfire on the ridge 300 yards east of the ravine portended the defeat of Terrill’s brigade. While Terrill’s infantrymen and the eight guns commanded by Lieutenant Charles Parsons fired upon Donelson’s Confederates, another Southern brigade, led by Brig. Gen. George E. Maney, consisting of the 1st, 6th, 9th and 27th Tennessee Infantry regiments along with the 41st Georgia Infantry — about 1,500 men in all — marched toward Terrill’s position.

Parsons wheeled his eight guns toward Maney’s troops, and the ground shook as they blasted the Southerners. Lieutenant Colonel William Frierson of the 27th Tennessee wrote: Such a storm of shell, grape, canister, and Mini balls was turned loose upon us as no troops scarcely ever before encountered. Large boughs were torn from the trees, the trees themselves shattered as if by lightning, and the ground plowed in deep furrows.

Terrill, absorbed with the action of the guns, unwittingly ordered the raw 123rd Illinois Infantry Regiment to charge the fence. Maney’s 1,500 Confederates decimated the 770 troops, leaped the fence and rushed the hill, where they drove off the equally inexperienced 105th Ohio Infantry. Terrill’s brigade, shattered and demoralized, raced toward the west with Maney’s brigade hot on their heels.

The members of the 21st Wisconsin were ordered to lie down in the cornfield, where, because of the high corn and thick weeds, they could not see what was happening to Terrill’s brigade. Suddenly, the shattered remnants of that command burst through the corn. Bloodied and broken, the panicked troops raced for the rear, nearly trampling the Wisconsans.

General Terrill, dejected from the loss of Parsons’ battery, burst into the corn shouting, The Rebels are advancing in terrible force! Maney’s men, meanwhile, continued to push into the corn, but many men in the 21st could not fire for fear of striking Terrill’s soldiers.

Portions of Brig. Gen. A.P. Stewart’s Confederate brigade linked with Maney’s left flank, and the Confederate attack moved in one long line toward the west. On the ridge behind the cornfield Starkweather’s troops fired into the ravine, desperately attempting to halt the Southern advance. Members of the 21st began to fall, caught in a horrible cross-fire between Union and Confederate bullets. Sergeant Edward Ferguson of the 1st Wisconsin admitted that his fellow soldiers caused friendly fire casualties. He noted that many of [the 21st Wisconsin] I fear lost their lives in the shower of grape and canister now being poured out by the batteries on the rapidly advancing enemy. John H. Otto of the 21st knew that his fellow soldiers were dealing death to his regiment. Right now began our disaster, he wrote. The 1st Wis….now opened fire towards our front, killing and wounding a great number of our own men. I saw some of our men fall forward and backward. Now was the moment to fix bayonet and charge. But no order of any kind was given.

Some troops of the disorganized 21st Wisconsin had hardly formed when the Rebels struck the cornfield. As butternut uniforms entered the dry field, breaking the stalks and kicking up dust, members of the 21st fired a volley that momentarily staggered the enemy advance. Some soldiers noted that the Confederates were only 20 feet away when they fired. A brutal response soon came from more than a thousand Rebel muskets. Bullets came zipping and whizzing through and over the corn in [a] lively manner, [and for] the first time the men became acquainted with that peculiar hissing `zipp’ a bullet only can make, Otto wrote. Most of the Wisconsin officers were either killed or wounded. The raw regiment received no orders, and the men did not know if they should return fire or withdraw. Major Shumacher was shot several times and killed. Some noncommissioned officers finally ordered the men to continue firing, and the 21st let loose one more disorganized volley before the long Rebel line outflanked the few hundred soldiers still standing. At that point the regiment crumbled and broke in confusion.

The retreat was difficult. In addition to running out of the ravine, the regiment had to climb a high fence, maneuver out of the deep roadbed of the Benton Road (which many called a ravine) and then sprint up the steep slope to the safety of Starkweather’s guns. The entire retreat presented dangers, but the run up the slope was the most deadly. Otto recalled that while the troops climbed up the fence and ran up the hill, the men fell like leaves from a tree in the fall, and that as he scampered up the fence, Rebel bullets sliced the straps of his haversack and his canteen.

The panicked regiment raced past Starkweather’s guns. Several cried out, The Secesh are coming, run for your lives! As the 21st fled past Starkweather’s hill, the brigade commander ordered the 1st Wisconsin forward to defend the artillery. The 79th Pennsylvania, which had already engaged Stewart’s Confederates, was immediately south of Starkweather’s primary position on the ridge.

Forming with the 1st Wisconsin on the hill were Companies B and C of the 21st, up from guarding the ammunition trains. Arriving late on the battlefield, they found unbridled chaos. Evan Davis later wrote: already tired out without any water in our canteens we hasten on and came in sight of the battlefield. stampeded horses without riders tore through our ranks. comrades maimed and bleeding met us hastening from the battlefield to the rear. shells and musketry belching for the destruction and hell in front of us. it required considerable courage to move forward. The two companies, despite their fear, lined the ridge and awaited Maney’s attack.

While most of the 21st Wisconsin fled, the regiment continued the fight on Starkweather’s hill, manning cannons whose artillerymen either had been killed or had run away. Otto, a soldier named Lorenz Lowenhagen and other members of the 21st loaded four of the guns with double canister. They would not have to wait long for the attack.

The 1st Tennessee, a fresh regiment brought up from reserve, charged Starkweather’s left, while the remnants of Maney’s exhausted command, which had been fighting for more than two hours, attacked the Federal front. As they climbed the steep hill, the Union fire staggered the Confederate advance. According to Colonel Hume Feild of the 1st Tennessee, Starkweather’s artillery and its support was making terrible havoc with the right wing of the brigade…. Private Sam Watkins of the 1st Tennessee recalled: Such obstinate fighting I never had seen before or since. The guns were discharged so rapidly that it seemed the earth itself was in a volcanic uproar. The iron storm passed through our ranks, mangling and tearing men to pieces….Our men were dead and dying right in the very midst of this grand havoc of battle. Watkins added that eight Tennessee color-bearers were killed by one cannon blast. The Tennesseans withdrew to the base of the hill and prepared for another charge.

As the Rebels withdrew, Starkweather noticed that infantrymen were manning his cannons. Who runs this concern? he asked Otto. Colonel, Otto replied, we are running this business on shares, but here [Lowenhagen] serves as a captain without a commission. Starkweather answered, Give them hell. Lowenhagen, who was promoted to sergeant two days later, was later killed at Chickamauga and buried in an unmarked grave.

The Tennesseans again inched their way to the top of the hill, where a hand-to-hand fight erupted among the wheels of the guns. One Union artilleryman noted that the ground became literally slippery with blood as the contending armies grappled around the pieces. Captain George Bentley of Company B, 21st Wisconsin, ran a Confederate through with his sword, picked up that Southerner’s gun and shot another. He was then shot dead. Confederate Marcus Toney of the 1st Tennessee recalled: We had ten men killed in attempting to carry the colors. We lost some two hundred and fifty men in a short time. Our boys got so close to the battery that the smoke covered them. At least one of those color-bearers was shot and killed by Edward Kirkland, Company B, 21st Wisconsin. He killed one flag-bearer, but was immediately shot in the face and shoulder. Dozens were falling on both sides. Among the dead was Lt. Col. John Patterson of the 1st Tennessee, killed by a canister round to the head.

The 1st Tennessee routed the Union soldiers and took possession of Starkweather’s artillery. In the chaos, however, an order to retreat was mistakenly given to the Tennesseans, and they fell back to the base of the hill. During the attack, the Confederates placed Captain William Carnes’ artillery battery at the northern end of the battlefield, and from there they shelled Starkweather’s position. Perhaps it was one of Carnes’ shells that tore apart General Terrill’s chest, killing him. Terrill, muttering, My poor wife, my poor wife…, was carried off the field. He died the next morning.Starkweather assessed the situation. The Confederates had shoved back Terrill’s brigade and had captured Terrill’s guns. The bluecoats of the 21st Wisconsin, facing nearly five times their own number, had been driven out of the cornfield after losing a third of their force. Maney’s Rebels had made two desperate charges against Starkweather’s line, and hand-to-hand combat had once forced the Union troops from the ridge. Thirty-five of Bush’s artillery horses were dead, Stone had lost a similar number of animals, and scores of Union troops lay dead and dying around the guns and on the steep slope.

Starkweather decided to fall back. While his infantry held the ground, the colonel reported that the troops rolled back six of the 12 cannons by hand to a new and safer position…. The brigade re-formed on another ridge approximately 100 yards west of their original location. A mix of Starkweather’s and Terrill’s men filed around the guns, and the 1st Wisconsin regrouped behind a stone wall located on the northern end of the ridge. There, they awaited Maney’s inevitable assault.

During the fight, Colonel Sweet of the 21st had ignored his illness and left his ambulance, only to be shot in the neck and taken from the field. As his regiment re-formed, the colonel again left his ambulance and was struck once more, this time in the arm by a stray bullet. Sweet was then moved farther to the rear.

Since all of the 21st’s officers had been killed or wounded, Starkweather sent a Captain Goodrich of the 1st Wisconsin to command the regiment and lead it to the new position. Maney’s men continued the attack, and the battle raged with renewed intensity. Starkweather’s line, however, held firm. At one point, John S. Durham, Company F, 1st Wisconsin, grabbed his regiment’s tattered banner, ran between the two lines and planted the flag. He remained there until his commanders ordered him back. Durham received the Medal of Honor for that act of bravery. In the fray, Captain Morris Rice, of the 1st Wisconsin, captured the regimental colors of the 1st Tennessee. After the war, veterans of the 1st Tennessee disputed the claim that it was their banner, but the Wisconsin troops were convinced of it.

The Confederate attack finally ground to a halt after nearly five hours of fighting. On Maney’s left, Stewart’s regiments ran out of ammunition and fell back, opening Maney’s left flank to attack, and Union troops moved forward to enfilade the Confederates’ line. That fire, coupled with the counterattack by the 1st Wisconsin, forced Maney’s brigade back. The battle ended at sunset, and Starkweather withdrew his battered command to the west.

It is awful to think of the misery that there is in the Army after a battle, wrote Charles Carr of the 21st Wisconsin. Bragg’s 18,000 Confederates, who repeatedly attacked the Union lines, lost 532 killed, 2,641 wounded and 228 missing. Buell’s command also suffered. At least 894 Union soldiers were killed, 2,911 wounded and 471 missing. Most of these casualties were from McCook’s 1st Corps, which bore the brunt of the Confederate attack.

The desperate stand mounted by Starkweather’s brigade against the 1st Tennessee had saved the Union left flank, but My losses in officers and men [were] terrible indeed, Starkweather reported. Of his 2,500 soldiers, 169 were killed, 476 wounded and 103 missing. The 21st Wisconsin lost 42 killed, 101 wounded and 36 missing — one-third of its force.That night, the regiment passed one of the many structures that had been hastily converted into field hospitals. Michael Fitch described the grisly scene: The yard was literally covered with the wounded, dead and dying. The dead silence [of the night] was broken by the most painful groans of the wounded. A halt happened to leave the twenty-first in this yard for a few moments, where the men could look and learn the dire results of war and exposure. After their harrowing experience, the survivors well knew the dangers of armed conflict.

On October 9, members of the 21st Wisconsin buried their dead. The rocky ground was hard and dry from the drought, so the graves were dug only 18 inches deep. Thomas Allen of the 21st remarked that the dead soldiers are only put about two feet deep and the hogs are puling them out and chewin them up so that the battle field looks worse than it did after the fight…. Mead Holmes concurred, saying: It seems hard to throw men all in together and heap earth upon them, but it is far better than to have them lie moldering in the sun….It is a fearful sight [to see the dead Confederates]; and to think of all these soldiers having friends who would give any thing for their bloated, decaying bodies, now torn by swine and crows, — oh, it is sad!

The gruesome scenes shocked another member of the regiment, who recalled: Unless something is done the country is uninhabitable. It is surprising how quickly the dead become black, many lie with open eyes. One had died leaning against a tree [and] as we passed stared at us with that wild ghastly look that you could scarcely summon courage to meet.

The Confederates had won a tactical victory at Perryville, but the Rebel commanders realized that they were outnumbered. Nearly 40,000 other Federal troops were relatively unengaged during the fighting. The Confederates knew that if their exhausted troops faced these fresh Union soldiers, the result would be a wholesale slaughter. On the night of the battle, General Bragg withdrew 10 miles to Harrodsburg. Since Corinth had fallen and more Union troops were threatening Chattanooga, the Confederates retreated toward Tennessee. The Kentucky campaign was over.

Soldiers of the 21st forever remembered the Battle of Perryville as one of the hottest contests of the war. Members of the regiment bitterly recalled their placement in the cornfield. Fitch believed that the position [the regiment] was placed in by the commander of the division [Rousseau], and left in by the indifference of the brigade commander [Starkweather] was the refinement of cruelty. It was between the fire of the enemy and that of our own troops in its immediate rear.

Charles Carr wrote: I never want to witness another such a scene. It was perfectly horrid to see men in the prime of life cut down while defending their Country, and then not to see any good results from it, but such is the case. The men were no longer green to the horrors of warfare. Perryville had violently opened their eyes.

This article was written by Stuart W. Sanders and originally appeared in the September 2002 issue of America’s Civil War.

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to America’s Civil War magazine today!