Getting Past Hell

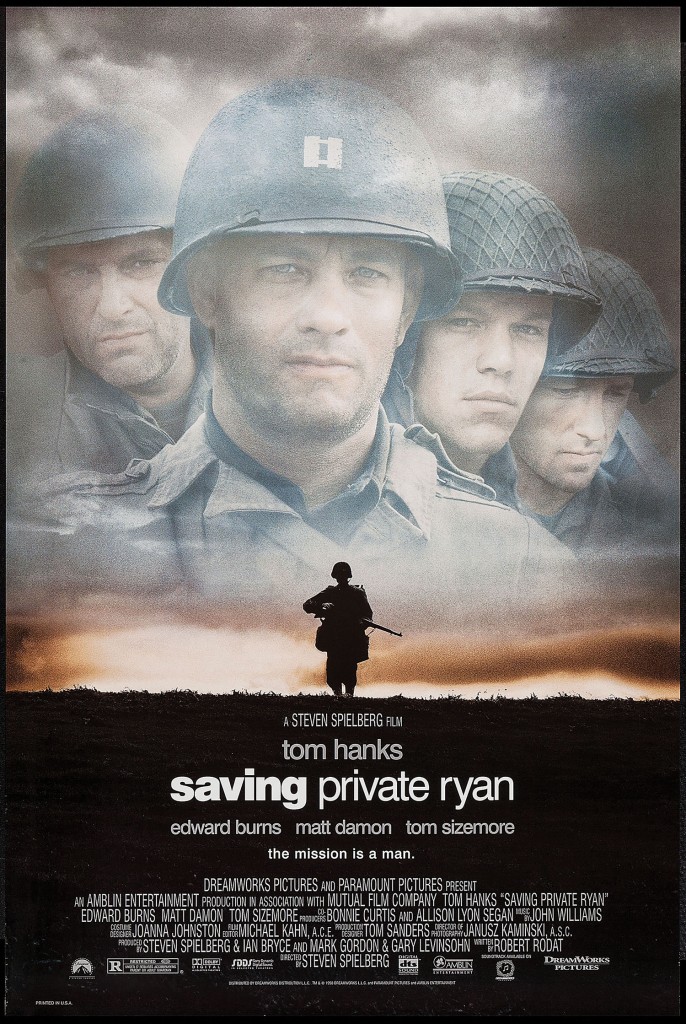

Saving Private Ryan begins with the battle for Omaha Beach. To achieve his horrific recreation of the events there on June 6, 1944, director Steven Spielberg spent $12 million and used 1,500 extras, including 20-plus actual amputees portraying men whose limbs are blown off. The result, critic Roger Ebert said upon the film’s release in 1998, was “as graphic as any war footage I have ever seen.” The Omaha Beach sequence also compellingly illustrates combat as a savage form of negotiation.

We associate negotiation with business and diplomacy, not war. But, as political scientist Thomas Schelling put it, “The power to hurt is bargaining power. To exploit it is diplomacy—vicious diplomacy, but diplomacy.” The essence of war is not violence, but the use of violence to get what you want. At Omaha Beach, GIs want those draws—gulches leading inland through which vehicles can advance. The Germans want to throw the invaders back into the sea.

The Omaha Beach sequence unfolds as a nightmare version of principles that negotiation expert William Ury articulated in his 1991 book Getting Past No. Ury, who co-founded the Harvard Negotiation Project to improve real-world conflict resolution, focused his book on disputes in which one party refuses to negotiate. While Ury aims for “win/win” outcomes, his principles can also be applied to the win/lose outcomes of battle. Indeed, the author frequently invokes examples from war.

Ury’s first principle is to approach an obstinate opponent only after thorough preparation. Exhaustive planning preceded D-Day, embodied in Saving Private Ryan by Higgins boats racing to shore. In one, Captain John Miller (Tom Hanks) and Sergeant Mike Horvath (Tom Sizemore) remind soldiers of what they learned in training. “I want to see plenty of beach between men,” says Horvath. “Five men is a juicy opportunity. One man’s a waste of ammo.”

As the boat’s ramp drops, enemy fire kills half the passengers. The film cuts to a pillbox overlooking the shore. Inside enemy soldiers are training two MG42 machine guns on the landing craft with merciless precision.

Those not instantly shot—or drowned when they go over the side trying to avoid the bullets—barely make it to the beach. Miller crouches behind a hedgehog obstacle. As he observes the carnage of the invasion’s near collapse, the sound drops out, illustrating another Ury principle; to embrace detachment, from which “you can calmly evaluate the conflict almost as if you were a third party.” More than a minute later, at the 10:26 mark, the sound returns.

“What the hell do we do now, sir?” a soldier yells to Miller.

Though Miller and Horvath urge men forward, most refuse, clinging to hedgehogs—“the only protection between us and the Almighty,” a man says. Miller, however, acts on Ury’s third principle—to adopt one’s adversary’s perspective—leading him to the fourth: reframe the situation. “Every inch of this beach has been pre-sighted,” the captain grimly explains. “You stay here, you’re dead men.” Each zipping German slug suddenly becomes an argument to advance.

Amid horrifying chaos Miller leads his troops to the more substantial but still tenuous shelter of a seawall, beyond which lie tangles of barbed wire. Miller calls for bangalore torpedoes—explosive-laden pipes for clearing just such barriers. Men assemble and detonate a bangalore, blowing a sizeable gap in the wire and cratering the sand. “We’re in business,” Horvath says. “Defilade. Other side of the hole.” Soldiers scramble to the crater’s far edge, a relatively safe space from which to assault the pillbox that is keeping them from the draw that is their objective.

In a perfect universe, the attackers would follow Ury’s fifth principle: let one’s adversary save face. “Build your opponent a golden bridge to retreat across,” he writes, quoting Sun Tzu. On Omaha Beach, face-saving is impossible, so Miller’s band goes to principle six: “Use power to educate.”

Germans start getting schooled at 19:05, as Americans reach the base of the pillbox. Miller spots a machine gun nest at the top of the draw. He orders a rush on a nearby defilade, laying down covering fire as his men, in full view of the MG42 crews, cross the deadly ground. Miller sends his sniper, Private Daniel Jackson (Barry Pepper), to a crater offering a shot at the nest. Jackson dashes into position and takes aim. At 21:41 he shoots a German gunner through the forehead and within seconds kills another. GIs scramble forward. Atop the bluff a murderous close-quarters fight develops, but now the Americans have the upper hand—and no more pity than their foes displayed earlier. A flamethrower blasts the pillbox from the rear. Defenders, aflame, try to escape through embrasures. “Don’t shoot!” a GI at the seawall yells. “Let ‘em burn!”

At 24:19, the dynamic shifts. Attackers and defenders now agree: the Americans control the beach. But it is not an amicable accord. When six German soldiers raise their hands in surrender, GIs shoot one. The others stay alive; these five will be this location’s only POWs. In a subsequent scene, GIs stand at a German trench, pouring fire onto its occupants. In another, as American infantrymen approach, two enemy soldiers raise empty hands and say something. The GIs fire point-blank. “What’d he say?” one asks. “Look,” his grinning buddy says, pantomiming surrender. “I washed for supper!”

The fight ends. Horvath shoves sand into a canister marked “France.” At 27:07 he says, “That’s quite a view.” Miller agrees. The camera pans past dead GIs strewn across the sand and floating in water red with blood. At tremendous cost, the Americans have finally gotten past no.

Originally published in the March/April 2016 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.