A specter haunts American politics. “Can Trump succeed in remaking the Republican Party in his populist image?” (Los Angeles Times). “The thing always to remember about Trump…is that he is a sham populist” (The New Yorker). “Is Trump a populist authoritarian?” (The Atlantic). Trump himself has no doubt. “We are transferring power from Washington, DC, and giving it back to you, the people,” he declared at his inauguration. “This moment is your moment.”

Populism means more than mere popularity. James Monroe and Warren Harding won with huge margins; no one thought either a populist. Thomas Jefferson and Franklin Roosevelt presented themselves as tribunes of the people, yet their to-the-manor-born manners kept the populist label at bay; you wouldn’t go to Monticello or Hyde Park to share a six-pack. The true populist must be like the people whose interests he has at heart. For fans of populism, this means being straightforward and simple; for critics, crude and contentious. Despite Trump’s fortune, an outer-borough yawp gives him a claim on the mantle.

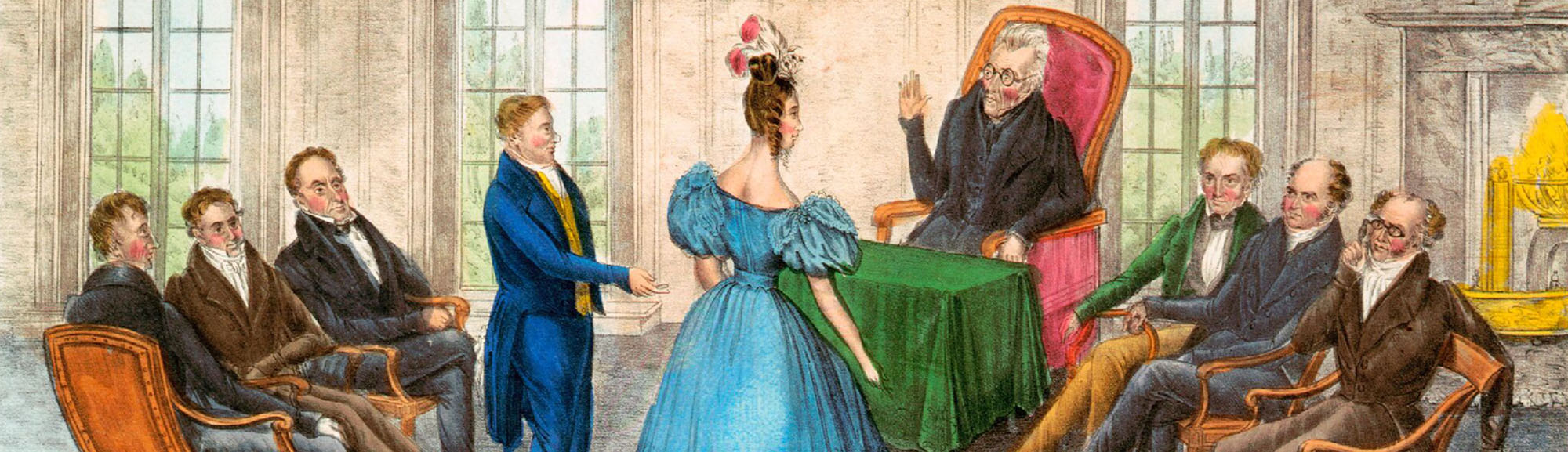

America’s past populist presidents were its two Andrews, Jackson and Johnson.

Both had rough youths in Carolina. Jackson’s parents, Scots-Irish immigrants, settled in the backwoods. His father died in 1767, three weeks before his son’s birth. Revolutionary War-related illnesses took his mother and two brothers. In the 1780s, he got education enough to become a frontier lawyer in western North Carolina, soon to be Tennessee. Andrew Johnson was born in North Carolina in 1808 to a porter and a washerwoman, both illiterate. He spent his youth as an apprentice, indentured to a tailor. After his release, he set up shop in Tennessee. His wife homeschooled him.

Both men became unclubbable successes. Jackson, a born warrior, rocketed to fame in the War of 1812, crushing the British at New Orleans. But in 1818 he drew official Washington’s ire by invading Spanish Florida on his own say-so—and hanging two Britons to boot. He said he had been chasing Seminole Indian raiders, and that the dead Brits had been their masterminds. Jackson escaped censure, and confirmed his own high opinion of himself.

Johnson, a shrewd investor, entered politics. He rose to Congress, Tennessee’s governorship, the U.S. Senate. Yet in his state and in the capital, he was an odd man out. He decried planters as a “pampered, bloated, corrupted aristocracy.” His main issue was homesteading—territorial land grants for small farmers, a program Southern colleagues opposed, fearing most grants would go to antislavery types. In the 1860-61 secession crisis, Johnson took his bravest stand, the lone Southern senator to back the Union. He fled Tennessee for his life, only returning, with Union troops, as the Lincoln administration’s military governor.

In person, Jackson and Johnson were bundles of rough edges. Dueling was illegal but widespread in the early republic, and Jackson a frequent practitioner. In 1806, a man accused his wife of bigamy; Jackson called him out, took a bullet in his chest, then shot his rival dead. Seven years later, Jackson fought an armed brawl in a Nashville hotel with Thomas Hart Benton, his aide-de-camp, and Benton’s brother Jesse, taking two slugs in his left arm and shoulder. Benton later became a U.S. senator and Jackson loyalist. Jackson’s reputation followed him into the White House. In 1829, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story welcomed the incoming Jackson administration as “the reign of King Mob.” John Quincy Adams, displaced by Jackson as president, called him “a barbarian” who could “hardly spell his own name.”

Johnson seethed with resentments that often flared. When he was a congressman, President James K. Polk, a fellow Tennessean, called him “vindictive and perverse in his temper and conduct.” Over the winter of 1860-61, chatting with a Republican congressman’s son, Johnson went off on Southern senators. He called Florida’s David Yulee a “miserable little cuss” and a “contemptible little Jew” and Louis Wigfall of Texas “a damned blackguard” who “never owned the hair of a n——.” All this, to a man he did not know particularly well. Sometimes alcohol loosened Johnson’s tongue. In March 1865, as veep on Abraham Lincoln’s victorious reelection ticket, Johnson followed his inaugural oath with a rambling and sodden speech. As Lincoln was going out to the East Portico of the Capitol to deliver his address, he told a functionary to make sure the new vice president did not speak again.

Jackson was elected president in 1828 and reelected in 1832, both times by landslides; Johnson became president, thanks to John Wilkes Booth, in 1865. Each won significant political victories against lively opposition. Jackson declared war on the Second Bank of the United States and, after the state of South Carolina announced it would ignore federal tariffs, vowed to collect them by force. The Bank withered and died, and South Carolina, while hewing to its states’-rights views in principle, backed down from them in practice. Johnson took Reconstruction policy into his own hands, in defiance of Radical Republicans who wanted Congress running that program. When Republicans retaliated by impeaching him, Johnson survived a Senate trial by one vote.

In his eight post-White House years, Jackson saw disciples Martin Van Buren and James Polk succeed him. Johnson never won his own presidential nomination, but was reelected to the Senate in 1875; after serving in a short special session, he died of a stroke.

Jackson stayed popular. He made the $20 bill in 1928; “The Battle of New Orleans,” written by Jimmy Driftwood and sung by Johnny Horton, was 1959’s No. 1 pop song. For years, the Democratic Party sponsored yearly Jefferson-Jackson Day dinners; “Jacksonian” still means populist. Johnson was never so honored, but John F. Kennedy thought enough of him to enshrine Edmund G. Ross, who voted to acquit in Johnson’s impeachment trial, in Profiles in Courage.

Lately the tide has turned. Jackson, an unrepentant slave holder and zealous Indian fighter, is losing his spot in our wallets to Harriet Tubman. Civil rights-era historiography admires the Radical Republicans and paints Johnson in the gloomiest light, as a defender of “white man’s government.”

Populism is no panacea assuring White House success. Populists can win big, even battles they should have lost. But like politicians—nota bene, President Trump—they too can fail and fumble. There is something egalitarian—populist, even—about that.