Japanese weapon straight out of a pulp science-fiction magazine created a lot of problems for the U.S. government in the waning months of World War II—problems not of national defense, but of public information and morale.

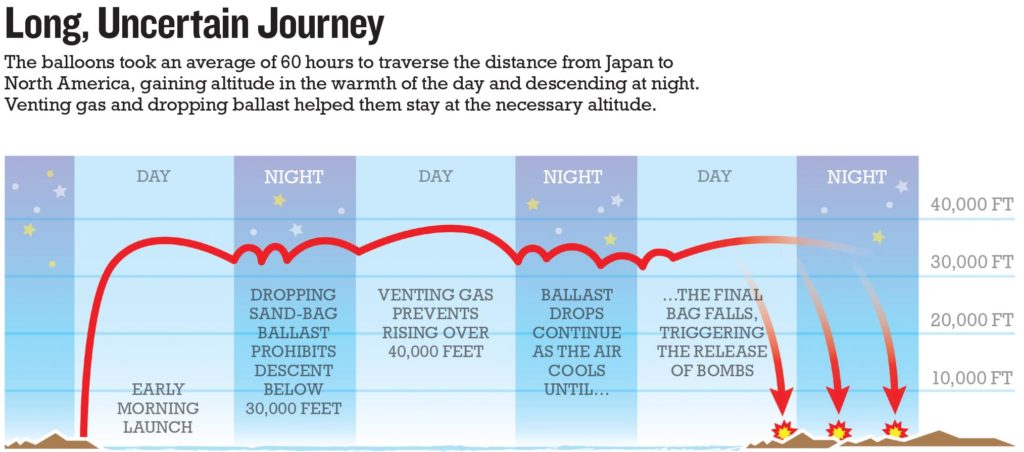

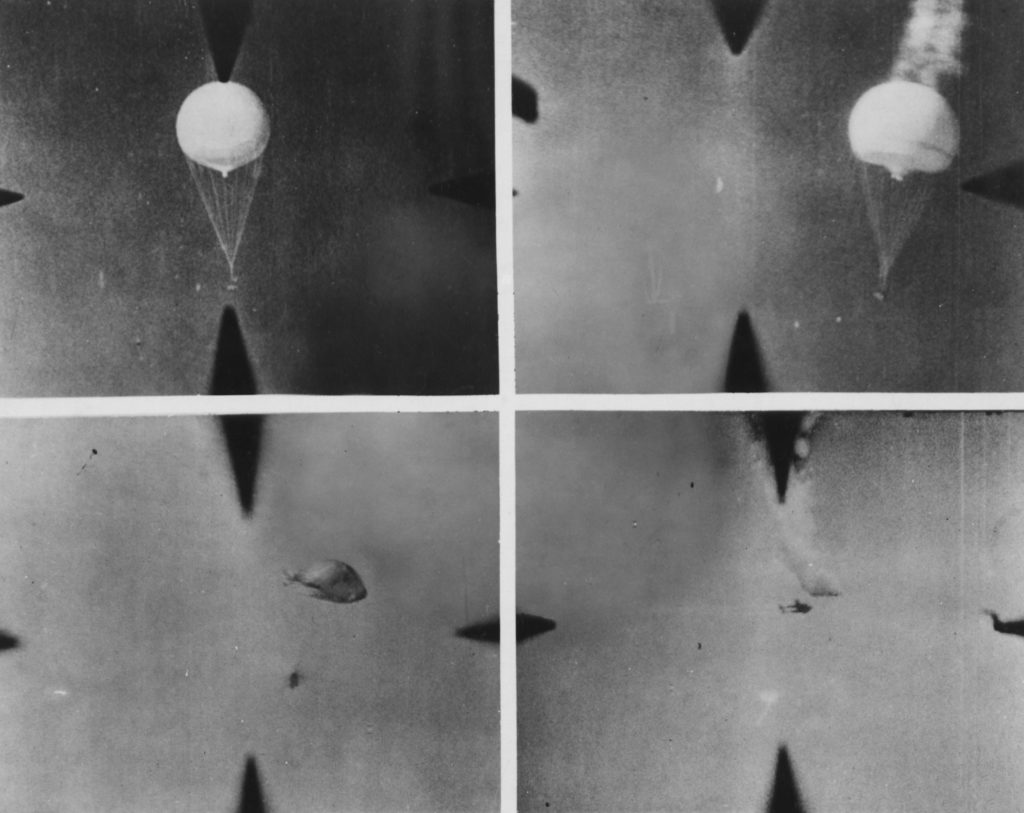

The weapon was a huge balloon made of four layers of impermeable mulberry paper. Each measured 33 feet in diameter, was inflated with 19,000 cubic feet of hydrogen, and carried ordnance—usually a 26-pound incendiary or 33-pound high-explosive bomb, along with four 11-pound incendiaries. The plan was to have the balloons (fusen bakudan in Japanese, meaning “fire balloons”; known to the Imperial Army by their code name, Fu-Go) waft across the Pacific on the jet stream that blew eastward from Japan some 30,000 feet above the earth’s surface. Because hydrogen expands when heated by the sun and contracts in the cool night air, the balloons were equipped with devices to vent hydrogen when they rose above the jet stream and jettison ballast when they fell below it. When all the ballast had been dropped, the balloons—ideally having traveled the 6,200 miles to hang in the air over the United States—would begin releasing their bombs.

Japanese officials estimated that only 10 percent would complete the journey, but they hoped that the balloons, landing at random sites to destroy buildings or set off fires, would incite terror among the American population.

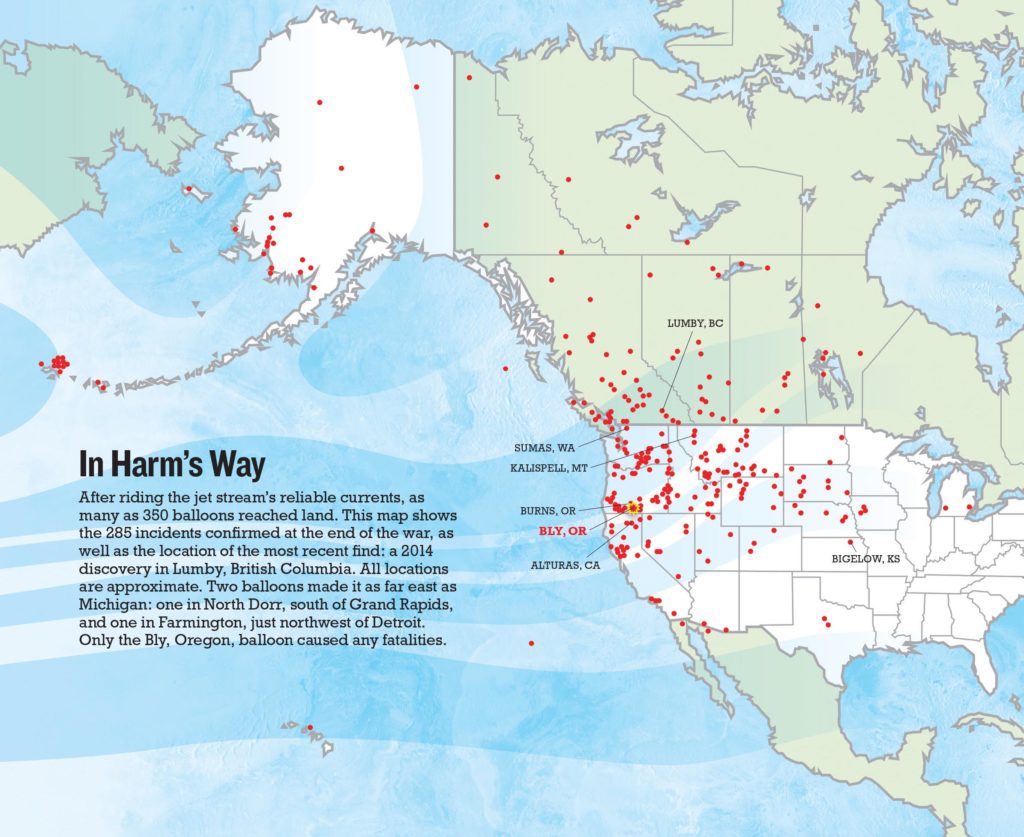

Beginning in November 1944, at the start of the jet stream’s strongest annual period, the Japanese deployed about 9,300 balloons from 21 launch sites in Japan. An estimated 1,000 reached North America, with more than 300 balloons documented. The first-ever weapons with intercontinental range, the balloons drifted as far east as the Great Lakes. But the biggest concentration was in the Western states (see “In Harm’s Way,” map below). Many of the bombs did not detonate at all, and those that did—with one noteworthy exception—caused little damage. The November launch meant that when the bombs did land and explode, the terrain was typically cold and wet, and not susceptible to raging fires.

But while the balloon bombs did not present a serious threat to U.S. safety, the potential for panic was real. To prevent hysteria, the U.S. government developed a policy mixing candor and secrecy that relied on a strong “zip-your-lip” ethos which was a component of homefront patriotism.

The U.S. government’s public information response went through three distinct stages, which shifted along with knowledge of the attempted attacks. When evidence of the balloons first surfaced, authorities were perplexed, and Phase I of the public response was to admit that uncertainty. Only after it became clear that these were Japanese weapons did Phase II begin, with the government trying to contain public knowledge of the devices. But after six people were killed in an encounter with a balloon-borne bomb near Bly, Oregon, the government’s public information policy changed again; in Phase III authorities warned citizens of the dangers of the devices. By then the Japanese had abandoned the effort, but scores of the balloons and their deadly cargo still remained in off-the-beaten-path locations.

APPARENTLY THE FIRST of the balloons to be discovered in the States landed around November 9, 1944, some 50 miles southwest of Reno, Nevada. By the time military experts got around to investigating it, there was nothing left but a few scraps. Residents of Thermopolis, Wyoming, reported seeing what they assumed was a parachute descend in early December; authorities found some bomb fragments near a coal mine and took them to the Army Air Base at Casper, Wyoming.

Then came one near Kalispell, Montana, discovered on December 11 by a father-and-son team of woodchoppers, O. B. and Owen Hill, who thought they had come upon a parachute fragment, and assumed from the lettering that it was Japanese. The Hills brought it to the Butte FBI office, where analyses of the amount of snow on the balloon concluded it had been on the ground at least since November 25. On December 18 the bureau issued an official announcement about the discovery, identifying it as part of a balloon that had had an incendiary device and detonator attached.

With no one able to figure out exactly what this debris from the sky was, the balloons were not front-page news. But they weren’t secret either. Local newspapers ran stories: in Nevada’s Mason Valley News on November 17, in the Northern Wyoming Daily News on December 8, in the Independent Record of Thermopolis on December 14. The Associated Press moved a story based on the FBI report that ran in many newspapers across the country on December 19. On January 1, 1945, the AP ran another story—just three paragraphs long—about a balloon found the day before, lodged in a tree in the forest west of Estacada, Oregon, and “similar to the one found near Kalispell.” This time the FBI refused further comment. But it became increasingly clear that the discoveries so far were not isolated incidents. In the week following the Estacada discovery, fragments of seven more of the Japanese balloons were found: two in Alaska; two near Medford, Oregon; two in California; and one in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan.

Inevitably, more press coverage followed. Newsweek and Time magazines jumped onboard with short items in their first issues of 1945. But the writers clearly knew nothing more than what the FBI had announced a couple of weeks earlier. The Newsweek article, headlined “Balloon Mystery,” summed up the theme of both newsweeklies: something is going on, but we have only questions, no answers. “Had the balloon carried any passengers? If so, where were they?” Newsweek asked. Time speculated: “The balloon had presumably been launched from a submarine. But why? If it had carried men, where had they parachuted to earth?”

Portland’s The Oregonian not only put the story on its front page, but ran a picture of troops from the Western Defense Command (WDC) hunting through the woods for more balloon parts.

At President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s January 2, 1945, press conference, Earl Godwin, NBC’s chief White House correspondent, asked, “Have you anything that might interest the public about the possibility of a spy offensive as indicated by these paper balloons?” FDR’s on-the-record answer: “Quite frankly, I haven’t got any more information than you have. Obviously, the first thing to do is to find out the origin of the balloons. That is not always easy.”

THE ONLY FORMAL CENSORSHIP the United States imposed on the press during the war was on overseas reporting. But Washington also exercised substantial control over the domestic war news Americans could read and hear by pressuring reporters and editors to be ever-aware of the need for discretion.

In January 1942 the U.S. Office of Censorship, which reported directly to President Roosevelt, had issued a voluntary code that newsmen were expected to follow. It implored them not to disseminate any news that could help the Axis. The censorship office promised to give quick responses to questions from the press about whether something could be published, and established a 24-hour hotline to field press inquiries. The office not only kept its promise of giving timely answers, but when the answer was “no,” usually gave a confidential explanation of why the information had to be kept secret. There were no legal penalties for violating the code, unless the information release was so egregious that it could be prosecuted under the 1918 Espionage Act—an action considered just once and never invoked.

Utah State University’s Michael S. Sweeney, who wrote the definitive history of the Office of Censorship, says: “Civilian censors could cajole, suggest, argue, and threaten but had no authority to punish beyond publicizing the names of violators. They did not need such power. The vast majority of journalists endorsed the codes as well as the administration of them.”

Editors went out of their way to comply. Newspapers that ran the initial stories about the bombs, for instance, first checked with the censorship office to see if the articles would trigger the code’s caution about items that discussed “operations, methods, or equipment of the United States, its allies, or the enemy.” The office gave them all the green light.

None of this pleased the military, which realized that even stories that were little more than conjecture could confirm to Japan that the balloons were reaching the U.S. interior. The Oregonian story was the last straw for Brigadier General William H. Wilbur, WDC chief of staff. Under his orders, intelligence officers on January 2, 1945, phoned the three primary wire services and six other major news outlets and asked them to hold off making public any details of any balloon landings until further notice. The press response: let’s see what the Office of Censorship has to say.

In fact, the office had a policy against requesting the national press to refrain from publishing stories that had already appeared in local outlets. Byron Price, the executive news director of AP whom Roosevelt had tapped to head the office, refused to waive that policy. But other government entities put pressure on Price and in less than a week he reversed himself. He sent a confidential memo to all American news outlets warning that “any balloons approaching the United States from outside its borders can be enemy attacks” and imploring that there be no dissemination of news about locating remains of such balloons, for doing so would “aid the enemy.”

As they had throughout the war, reporters and editors censored themselves. Citizens continued to uncover balloon scraps at sites including ones near Julian and Red Bluff, California, in late January; near Rapid City, South Dakota, and Burwell, Nebraska, in February; and in Pocahontas, Iowa, in mid-March. By May 12 the list of balloon incidents the WDC compiled had reached 150. But in those five months, not a word about the balloons appeared in print or in radio newscasts. As John Willard, then a reporter at the Helena (Montana) Independent Record, recalled more than 50 years later, after the Kalispell incident “we heard stories about other balloon bombs landing around the state and talked about them in the newsroom. But we just didn’t write stories about them.”

The government, though, could hardly hope to still the locals at the sites involved. Instead, it tried to keep the stories from getting out of hand. As Washington learned more about what the balloons were and their intent, the military and the FBI worked hand-in-hand to level with townspeople about the devices and underscore that it was their patriotic duty to stay mum about it all.

Typical is the way they handled the discovery on February 23, 1945, by farmer Edwin North of an intact balloon snagged in a tree some 30 miles north of Manhattan, Kansas. With the help of two neighbors, North deflated the balloon and carted it in a horse-drawn wagon to the nearby town of Bigelow. Bigelow postmistress Lena Potter told historian Bert Webber: “Ed brought the apparatus to me at the Post Office and asked my opinion. I said we’d best call the sheriff, who should take custody of the mysterious thing.” Sheriff Charles A. Anderson in turn handed the issue over to the U.S. Army Air Forces base in Topeka; the army immediately moved to contain news of the find—which North figured was by then known to at least 30 neighbors. FBI agents and soldiers formed teams that went through Bigelow door-to-door, asking residents not to tell anyone about the balloon.

At site after site, most people complied. They had been conditioned by a barrage of Office of War Information posters with slogans like “Silence Means Security,” “Free Speech Doesn’t Mean Careless Talk,” and “Loose Talk Can Cost Lives.”

EVERYTHING CHANGED ON MAY 5, 1945.

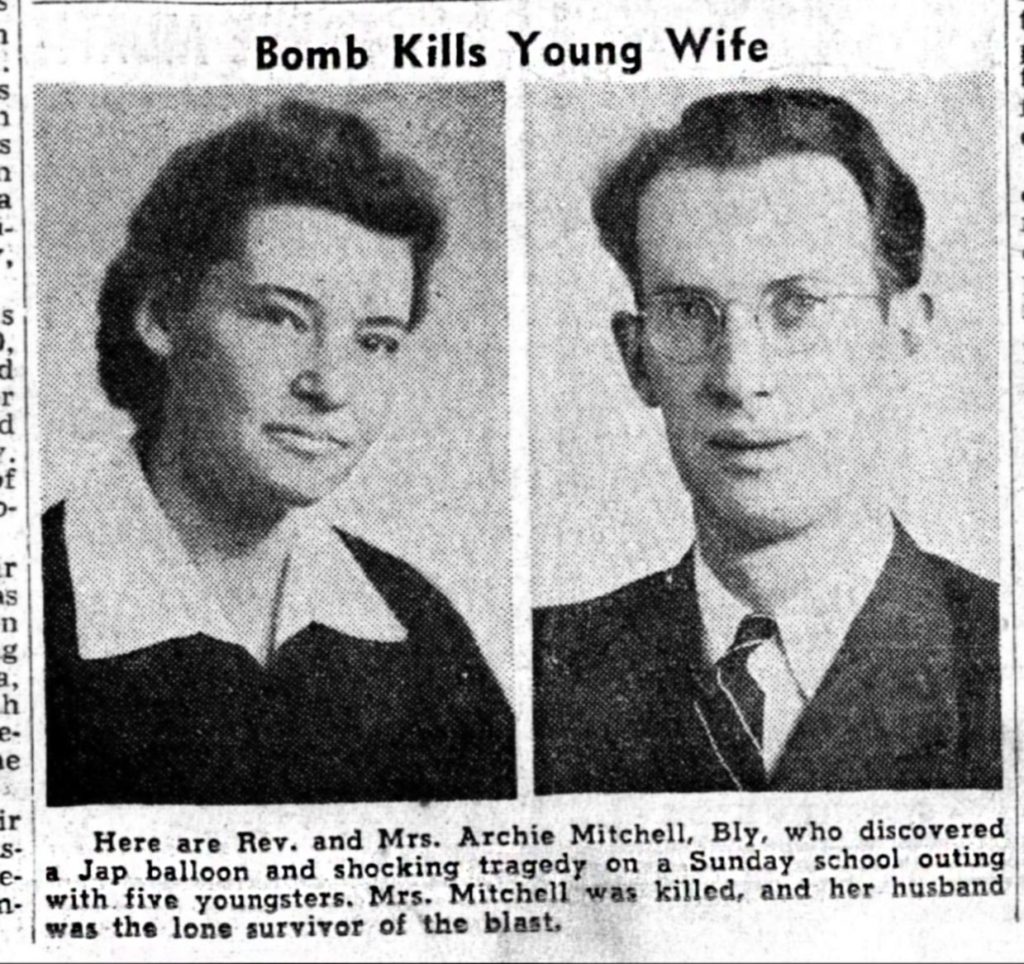

That was the day that Archie Mitchell, the pastor of the Christian and Missionary Alliance Church in Bly, Oregon, and his pregnant wife, Elsie, took five of their Sunday school students on a fishing trip to Leonard Creek, which wends among ponderosa pines near Gearhart Mountain, eight miles northeast of Bly. Archie parked the car and began unloading food while his wife and the kids, ranging in age from 11 to 14, began looking for a suitable picnic spot. One of the youngsters found something strange on the ground, and apparently pulled at it or gave it a good kick.

It was a balloon bomb, and the movement set off an explosion.

Archie’s frantic efforts to extinguish the flames were fruitless: his wife and all five children were dead. As a monument now marking the spot notes, it is the “only place on the American continent where death resulted from enemy action during World War II.”

It was not an incident that could be kept under wraps. A joint funeral in Klamath Falls for four of the young victims drew 450 attendees. But the military tried to obfuscate. An intelligence officer from Fort Lewis in Pierce County, Washington, secured the site and told reporters to identify the explosion as being of “unknown origin.”

Two results of the tragedy ushered in Phase III of the balloon bomb public information response: not only allowing publication about the weapons, but encouraging it.

One impetus for that change was that the term “unknown origin” was triggering the very wave of fear that news blackouts had been meant to stifle. Rumors began spreading. J. R. Wiggins, managing editor of the Pioneer Press and Dispatch in Saint Paul, Minnesota, kept a log of calls to his paper in the weeks immediately after the Leonard Creek explosion; it quickly reached three dozen. The callers were “scared, curious, calm, and furious,” he said. On his list: that the U.S. was being bombed by robots; that parts of San Francisco had been wiped out by secret bombs; and that balloons carrying poison gas were landing “and when they let go folks anywhere near are killed.”

The second development was remorse on the part of military intelligence officials. Perhaps the Oregon deaths could have been prevented had the population been warned to stay away from any balloon fragments they found and call authorities. Almost immediately after the explosion, army intelligence issued a short statement intended to be taught to school children and read at meetings of civic clubs in towns throughout parts of the country west of the Mississippi. The statement said that while the press had agreed not to publicize the incidents, Japan had launched attacks on the United States via big balloons. The balloons were dangerous, and no one should pick up any strange objects they found.

That public information campaign sparked vehement pushback by the press against the Office of Censorship. A memoir by the office’s Byron Price relates that within days of the statement’s release, reporters “inundated” him with demands that they no longer be muzzled about the story since the public was being handed a swath of balloon information. Price in turn complained to Major General Clayton Bissell, director of army intelligence, and to Admiral R. S. Edwards, deputy chief of naval operations, trying to get them to issue an official acknowledgement of the balloon attacks. The army was willing to work on the wording of such a statement, but Edwards adamantly resisted, saying, according to Price’s memoir, the news would “kill Americans.”

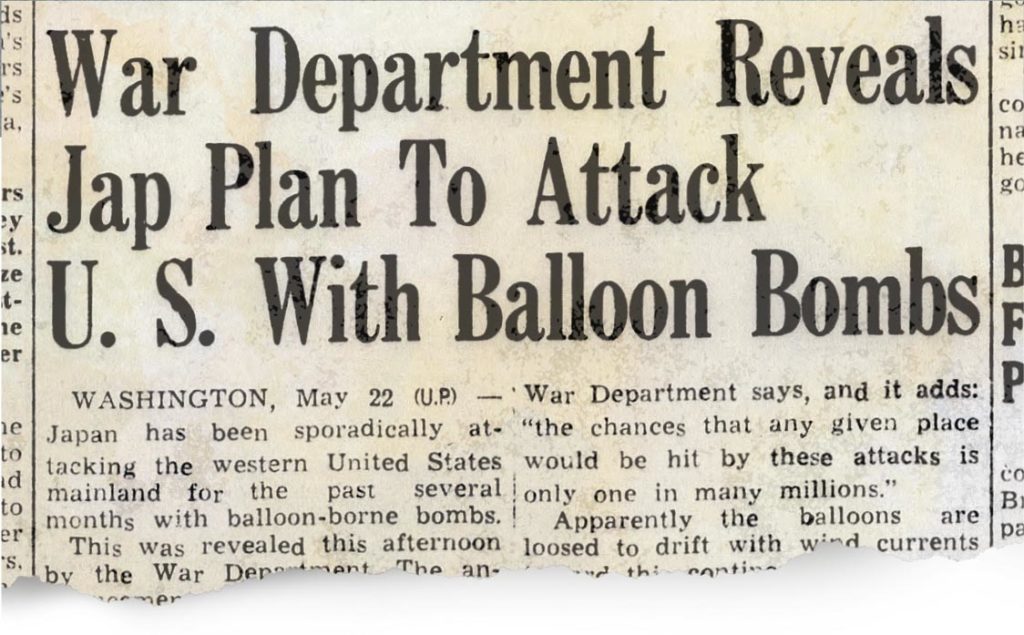

By May 20, 1945, editors at the Chicago Tribune had readied a story about the balloons and were prepared to publish it. The New York Daily News was about to run an article saying that the Tribune was on the verge of printing a balloon story. Price cajoled the Daily News to kill its item and told the Tribune to hold off for two days. He went over Edwards’s head to chief of naval operations Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, who saw the force of Price’s argument and approved a release. Just after noon on May 22, the press got an alert to expect a joint communiqué from the army and navy about the balloons later that day.

The statement acknowledged the existence of the balloon bombs, but insisted the attacks were so scattered and ineffective that they were no cause for alarm and that the chances of a particular spot being hit was one in a million. The statement admitted that the weapon had killed six persons, but gave no further details. Nine days later the Office of Censorship realized that it was impossible to continue suppressing the link between the balloon bombs and the Leonard Creek deaths, and okayed publication of the story. The Associated Press, which had interviewed Archie Mitchell and had a full story with the names of all the victims ready to go, immediately released it nationwide.

The Office of Censorship advised reporters and editors that they should continue to refrain from reporting on specific balloon landing sites unless the information came from the War Department. The government lived up to its end of the bargain. In early June, for instance, it announced that three balloons had fallen in southern California “in recent months” and that one had gotten as far as Michigan. The office approved a June 27 story in the Salt Lake City Deseret News that detailed an interview with an unnamed sheriff in the western part of the state who struggled to recover a Japanese balloon that had, after touching ground, started to rise again. “I fought that darned thing for 55 minutes before it dropped to the ground and I succeeded in tying it to a choke cherry bush,” the sheriff told the newspaper.

The press was asked to be careful that their stories did not create hysteria. Most coverage focused on public safety. Time immediately ran a story headlined “Picknickers Beware”; a Newsweek story was captioned “Mustn’t Touch.” The Associated Press story about the Michigan balloon emphasized that it had no explosives attached, so members of the public should beware that bombs could be lying some distance from the landing site.

BYRON PRICE HAD PROMISED the press that the self-censorship program would end as soon as the war situation made that possible. After the August 6 and 9 atomic bomb attacks on Japan, it was evident there need be no more worries about news stories helping the enemy. When Price learned on August 15 that the official V-J Day was still two weeks away, he inveigled President Harry S. Truman to end press censorship immediately. Truman signed the order at 3 p.m. that day. Price posed for an AP photograph hanging an “Out of Business” sign on the Office of Censorship door.

Shortly later the AP sent subscribers a story detailing what was known about the bombs, including that remains of 230 balloons had been found but that “many more were sighted and still are being recovered in isolated areas, where unexploded bombs remain a menace.” Outlets near balloon landing sites immediately capitalized on their new freedom, running stories they had readied earlier. For instance, the August 23 issue of the Marshall County News of Marysville, Kansas, ran a piece under the headline “Story of Japanese Balloon Which Fell Near Bigelow Can Now Be Told.” And the picture that Kansas farmer Edwin North had taken with his Kodak Hawkeye camera of a balloon stuck in a tree could finally be published; the AP paid him $10 for the rights.

Although no one in the United States knew it at the time, the Japanese, lacking information about the fire balloon program’s effectiveness, had abandoned it in early April 1945. Though the U.S. government had to employ three different approaches, its policy of handling balloon bomb information to neither panic the public nor give the Japanese valuable data had worked. As a May 29, 1947, New York Times story put it: “Japan was kept in the dark about the fate of the fantastic balloon bombs because Americans proved during the war they could keep their mouths shut. To their silence is credited the failure of the enemy’s campaign.”✯

This story was originally published in the February 2018 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.