Last time out we witnessed the German army preparing for World War II. The Great Fall Maneuvers of 1937 took place in the north German region of Mecklenburg, and showed a Wehrmacht that was out of the huddle, had its head down, and was driving inexorably towards an aggressive war of conquest against its neighbors. The star of the show was a new formation called the Panzer Division, one that was going to give a lot of other armies a lot of headaches in the next few years. Beyond that, the maneuvers showcased some distinctively German military traits: a high level of aggression, independent commanders allowed to make their own decisions on campaign, and a willingness to court dangerous levels of risk.

What a different picture we get from the 1941 Louisiana maneuvers of the U.S. Army! In many ways they were a perfect distillation of an “American way of war.” First off, they were awfully late in getting started. We sometimes gloss over the fact today, but both world wars saw the U.S. sitting on the sidelines and missing most of the action. Think of it this way: World War II lasted six years, from the invasion of Poland on September 1st, 1939 to Japan’s surrender on board the USS Missouri on September 2nd, 1945. U.S. participation spanned less than four years of that total, a little over half the war. Of seven campaigning seasons, the U.S. missed the first three and was active only in the final four. World War I was even worse: of five campaigning seasons, the U.S. took part in just one, the last.

It wasn’t until 1940, when the Wehrmacht overran France and drove the British off the continent, that the U.S began actively preparing for war. The country had made great strides, certainly. In September 1940, President Roosevelt signed the Selective Service Act into law, the first peacetime draft in U.S. history. Some 16,000,000 men registered for the draft that fall. By the end of 1940 there were 630,000 men in the army (13 divisions), and six months later (June 1941) there were 1,400,000 (36 divisions). The military budget for 1940, about nine billion dollars, exceeded all the military budgets combined dating back to 1920. As force levels exploded, big maneuvers became possible for the first time.

Nevertheless, by the time the army gathered for its first great field tests in the fall of 1941—the Arkansas maneuvers in August, Louisiana in September, and the Carolinas in November—world war had been raging for two full years. Japan had already overrun much of China, and the Wehrmacht had smashed one opponent after another in Europe and was even then in the midst of the greatest land campaign of all time: the opening drive into the Soviet Union, Operation Barbarossa. World War II was racing to a climax, in other words, and not only had the U.S. missed out on the action, it remained to be seen if it would see any action at all.

* * *

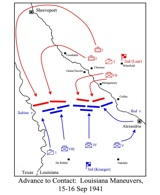

In operational terms, all three of these great maneuvers featured a similar approach. It was one that would have been familiar to previous generations of U.S. field commanders, especially Union generals in the Civil War. The Louisiana Maneuvers, for example, were essentially a teaching tool in battle management for an officer corps that had virtually overnight been tasked to lead mass armies in the field. “The field,” in this case, was the district bounded by the Sabine and Red rivers to the west and east and the city of Shreveport to the north. In Phase 1 of the exercise, both sides were given offensive missions. Red 2nd Army (under LTG Ben Lear) would cross the Red river on September 15th and invade the Blue homeland. Blue 3rd Army (LTG Walter Krueger) would move north to intercept the invaders and drive the Red force back across the river. The Blue side was big, but ponderous; Red was smaller, but equipped with two armored divisions (1st and 2nd). Essentially, the mission for both sides amounted to a large-scale advance to contact, the most basic of all military maneuvers, but one perfectly suited for this brand new army and its green commanders.

Lear soon found that even getting across the river was tougher than he expected. Due to limited bridging capacity, he had to send his 1st and 2nd Armored Divisions on a wide sweep north to cross the river at Shreveport and Coushatta. Krueger, meanwhile, spent the first two days of the maneuver carrying out a by-the-book advance by three corps abreast: VIII, IV, and V, moving from left to right (Map 1). On day 3, he launched an assault on Lear’s VII Corps along the Red river, which, after a promising start, settled down into a slugging match rather than a dramatic breakthrough. His numbers were eventually decisive here, however, and Lear had to give ground (Map 2). The next day would see Lear’s armored divisions launch an assault on Krueger’s left, which, after a promising start, bogged down in the face of Blue’s antitank guns (Map 3). This was the situation by the afternoon of September 19th when the whistle blew ending Phase 1. Nothing revolutionary or shocking had taken place—this was operational art by way of U.S. Grant, a classic evocation of an American way of war—but again, it was probably just what this army needed the most.

Click on maps for larger images.

And that is why Phase 2 is all the more shocking. Here, the young U.S. Army would show a very different face, one that, perhaps, its enemies in the upcoming conflict should have noted more carefully. Next week: “Patton’s Drive on Shreveport.”

For more discussion of the war, the latest news, and announcements, be sure to visit World War II magazine’s facebook page.