In the wake of their bitter war, Vietnam and the United States had to adjust to a new relationship.

Hanoi, the heart of the enemy camp, lay before me. I had fought its troops in many capacities—as a U.S. infantry company commander, Special Forces Operational Detachment Alpha commander, province adviser and then Defense Department planner of actions against the North. Yet here I was, in December 1975, helping a congressional committee open talks with that very foe to account for Americans who were still missing.

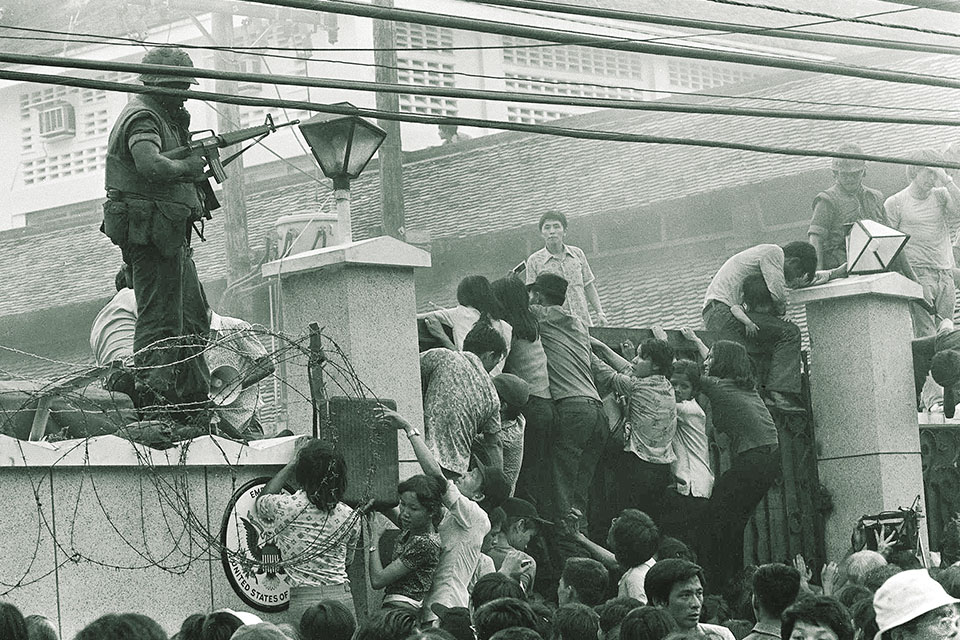

Seven years earlier, in 1968, I had left Vietnam on a stretcher, cared for by my “lady in white,” a Vietnamese nurse at a hospital in Long Binh. Seven months earlier, as Hanoi’s forces smashed into the Presidential Palace in Saigon at the end of April 1975, I had trashed all my Vietnamese language books, thinking I was finished with the country. A little over seven days earlier, I had been in Paris, meeting with Jean Sainteny, who had led French efforts to prevent his country’s Indochina war in 1946 and set up the talks leading to the Paris Peace Accords that ended America’s war in 1973. Together, we had arranged the December 1975 talks, the first postwar visit to Vietnamese officials. “They are full of arrogance right now,” Sainteny told me. “Let them absorb their victory and the future will get better.”

The scene in Hanoi confirmed his assessment. Numerous signs proclaimed the triumph, while newspapers and posters urged people to rebuild Vietnam with the same heroic effort that was used during the war and make the country a model for developing nations. Pictures of Ho Chi Minh were everywhere, often with the inscription: “Vietnam is one, from Lang Son [in the far northeast] to Ha Tien [in the far southwest].” The communists were still celebrating their victory, and soldiers who lived through it were still coming home.

I took a long walk in central Hanoi and struck up conversations with several people. I came upon a newspaper stand and purchased papers from a vendor. He could not believe I was an American, and as we talked a crowd of curious and friendly Vietnamese began to encircle us. Suddenly, two soldiers appeared across the street and blew their whistles. Instantly the crowd dispersed, leaving me alone with the news vendor. Although I had not detected a “tail” following me, I was not surprised to spot one. I then went into a book shop and, remembering a little Russian, asked for one of the Soviet publications. The lady rudely shoved the publication at me, most likely because she mistook me for a Russian. It was the only ugly exchange during my visit, but it turned out to be the first of several incidents over the years indicating popular resistance to pro-Russian and pro-Chinese government positions.

My deepest impression of Hanoi was its utter poverty. The city had been largely evacuated during the war. Loose gutters hung from dilapidated buildings. Women pushed carts loaded with sand to make bricks, and former soldiers in worn-out military garb looked for work.

Unlike Hanoi today—where traffic is so thick you take your life in your hands crossing the street—there were no cars; biking and walking were the only means of transportation. A bicycle storekeeper told me that a young man might offer a bicycle chain as an engagement gift to his fiancée. On one occasion the congressmen in our delegation went to the best store in town to buy gifts. I will never forget the shocked stare of the owner as the Americans ordered, one after another, antiques worth a year’s wages in Vietnam.

How could a country so poor and economically backward have defeated the greatest military and economic power in the world? Many have struggled to find the answer, but I saw it written above a huge picture of Ho Chi Minh in Ba Dinh square: “There is nothing more precious than freedom and independence.” The freedom was a stretch, as the government soon replaced the word “Democratic” with the word “Socialist” in the country’s name, but the importance of “independence” cannot be overstated.

Ho Chi Minh rose to power under the banner of the Vietnamese Independence League (commonly known as the Viet Minh). Independence was the driving force that propelled hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese to their deaths in what they called the American War. I visited the Museum of History, which exalts patriots of many generations, all in the name of independence. Many fought the French and Americans, but most fought against the Chinese. I also walked along the banks of the Lake of the Return of the Sword. Vietnamese schoolchildren are taught the story of a golden turtle that came out of the water to present the patriot Le Loi with a sword. After using that sword to drive the Chinese out of Vietnam, he went back to the lake and returned the sword.

On the December 1975 trip, I sat alongside four members of the House POW/MIA Committee, led by U.S. Rep. G.V. “Sonny” Montgomery of Mississippi, during meetings with Vietnam’s foreign minister and the Communist Party leadership. We came to initiate the long process of accounting for more than 2,400 Americans listed as prisoners of war or missing in action.

As Sainteny predicted, the Vietnamese Foreign Ministry’s position was harsh and direct: “You came to bomb us. Your soldiers committed atrocities. Your war leaders are as guilty as the convicted Nuremberg war criminals. America is like a hit-and-run driver who smashed Vietnam and then went home.”

Our most important concern was the possibility that Americans were still being held in Vietnam even after the POW releases in February and March 1973. Families of missing servicemen not among the freed were left in limbo. We presented evidence of missing Americans known to be alive on the ground—80 percent were airman who had been shot down—and a list of specific men believed to have died in captivity.

“We are not holding any American prisoners as a result of the war,” Prime Minister Pham Van Dong told us the next day. That left little hope for the return of additional POWs because once he made that definitive statement, any subsequent release of prisoners would make him appear to be a liar.

“Vietnam is a large country with lots of jungle terrain,” we immediately replied. “It could well be that American servicemen remain hidden in its vast area.”

Dong reiterated his position: He had no expectation that any living POWs still existed. His statement, however, left unanswered questions about missing Americans who were not servicemen, such as civilian workers and CIA operatives, and thus were not being held “as a result of the war.” We asked about them, and in 1976 there was a general prisoner release of 50 detained Americans and their dependents.

We also talked to Vietnamese officials about the remains of American servicemen killed in the war. We presented the numbers and information on specific cases that we had obtained from the intelligence community and the National League of POW/MIA Families. Hanoi denied having large numbers of remains but nonetheless used them as a valuable bargaining chip in negotiations, lending credence to reports that Vietnam had 400 remains “on the shelf” to deal out piecemeal for money or political objectives. In any case, we accepted the remains of three American servicemen and returned them to their families.

The next day, the Vietnamese revealed the real reason for their interest in the talks. “We have a letter here from your President Nixon,” announced Deputy Foreign Minister Phan Hien. He read aloud Richard Nixon’s letter stating that the United States would pay Vietnam $3.25 billion in postwar reconstruction aid. Hien also produced a 20-plus page report from the Joint Economic Commission, established by the January 1973 Paris Peace Accords, which listed purchases to be funded by the U.S., including dry docks, bulldozers and construction equipment.

The Vietnamese officials argued that they were owed the money not only to fulfill the Paris commitment but also to compensate Vietnam for the “war crimes” of U.S. troops, an indictment intended to induce a sense of guilt in Americans and a favorable attitude toward payment of reparations.

The Nixon letter was a shock to our delegation. Before leaving for Vietnam, our committee met with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. We had heard rumors of a secret agreement with Hanoi and asked Kissinger if there was any such agreement. He replied that everything had been made public. When we returned to Washington, we tried to get another meeting with Kissinger but weren’t successful.

We decided not to make the letter public because it was irrelevant since Congress would never authorize the $3.25 billion for Hanoi. Additionally, Vietnam violated one of the conditions for the funds when it reneged on the peace agreement and attacked South Vietnam in the spring of 1975.

On the final day of our discussions, Dec. 22, 1975, the tone of conversation abruptly became more conciliatory. The American delegation said we heard that the Soviets had a foothold at Vietnam’s Cam Ranh Bay and wouldn’t allow ordinary Vietnamese to even go near the base. “The Soviets are our friends,” Dong stated. “Maybe someday the U.S. Navy will be allowed to use the base.” In another comment, he said, “We look to the future, and not to the past.”

Those words from the government, coupled with the positive attitude of the Vietnamese we met on the street, gave me a modest degree of optimism. Despite the problems that remained, I felt there was hope for the future.

During subsequent visits over the next decade, however, I saw Vietnam become tied in a vindictive ideological straitjacket. “Re-education camps,” supposedly established to indoctrinate former South Vietnamese soldiers and civilians in communist philosophy, were, in reality, harsh prison camps. When meeting with former re-education camp prisoners in Southeast Asia, I saw that many had been tortured. Many more were killed, and hundreds of thousands fled the country by sea, becoming the “boat people.”

The government particularly persecuted the children of American fathers and Asian mothers. During a 1984 visit to Saigon (the name still used by many Vietnamese even after the official change to Ho Chi Minh City in 1976), an emaciated woman wearing a beat-out straw hat said the “Amerasians” left in Vietnam were systematically discriminated against and not allowed to find meaningful work. She and others had difficulty feeding their children, and her children faced harassment in school.

Vietnam’s Hoa population, residents of Chinese descent, were frequently harassed. On that 1984 trip, I took congressmen from the Veterans Affairs Committee to a restaurant atop the Rex Hotel, where Saigon-based journalists used to report on the war. Our Hoa waiter asked me to deliver a letter to his brother in the United States because he was not allowed to send mail outside Vietnam. He slipped the letter under my coffee cup. I also went to Saigon’s Cholon district, an ethnic Chinese enclave, and learned that hundreds of shops had been shut down and thousands of Hoa forced into exile.

One reason for the harassment of the Hoa was Vietnam’s war with China in early 1979, an offshoot of fighting between Vietnam and Cambodia as ancient ethnic conflicts re-emerged in those two countries after the war with America ended. Border clashes led to pillaging of whole villages on both sides of the Vietnam-Cambodia boundary. In December 1978, Vietnam invaded Cambodia and installed a friendly regime in Phnom Penh, despite opposition from China, which considered Cambodia to be within its sphere of influence.

To punish Vietnam, Chinese troops crossed Vietnam’s northern border in five places in February 1979. Although bloodied by the Vietnamese militia, China succeeded in occupying six northern provinces. Six weeks later the Chinese withdrew and ended the conflict. Afterward, I interviewed both Vietnamese and Chinese military officials for a publication on Chinese warfighting. While the Vietnamese felt they taught China a military lesson, the Chinese claimed to have taught Vietnam a lesson by punishing it for “arrogance.”

Vietnam continued its hard-line course under Party General Secretary Le Duan, who incessantly promoted communist ideals, collectivized agriculture and pushed state enterprises. “Capitalists are like sewer rats,” he said. “You have to pound them down wherever they pop up.” Poverty worsened, and unemployed men from the countryside stood on city street corners waiting for work. During multiple visits in the 1980s, the men told me of extreme hardship and even starvation in their home provinces. They were desperate.

By the time Le Duan died in July 1986, riots had broken out in parts of northern Vietnam. New party leadership, emulating the perestroika reforms in the Soviet Union, declared a reformist policy of doi moi (renovation), which allowed capitalism to gain a foothold and permitted greater freedoms at the local level. The Vietnamese government promoted U.S. investment to suck in as much American technology as possible and stimulate indigenous production. While representing a major U.S. corporation that sought to establish a joint venture with a Vietnamese government corporation in charge of mail and telecommunications, I found my Vietnamese hosts to be savvy negotiators.

By the end of the 1980s, the economy strengthened. On the street it seemed that every Vietnamese was an entrepreneur, from the boy selling cigarettes to the bicycle taxi driver who doubled his fee for foreigners. People who had worn drab military clothing or black pajamalike clothes for years suddenly appeared in multicolored fabric; children began wearing Mickey Mouse shirts.

People began to speak more freely without the fear of reprisal. While talking with several men in Hanoi I mentioned the elaborate homes being built on the city’s Red River dike. “These are not for us,” they said, “but for [Communist] Party and other elites who have money.”

I also met with many veterans of the war, sharing experiences in a soldier-to-soldier fashion. Whenever I mentioned my respect for their bravery, they reciprocated the compliment. One man who fought at Dien Bien Phu, where the Viet Minh crushed the French army in May 1954 and brought an end to France’s presence in the country, invited me to his home for tea.

During the decade that followed normalization of relations between Vietnam and the United States in July 1995, religious freedom began to improve, and in 2006 the State Department removed Vietnam from its list of countries with egregious violations of religious freedom. However, some restrictions still remain. Although Hanoi tolerated Buddhism and approved the Buddhist Sangha (community) of Vietnam, it banned the Unified Buddhist Sangha prevalent in the south and put its leaders under house arrest. Suspicion of Protestant denominations persisted for several years, largely because they were linked to Montagnard ethnic minorities who tended to resist authoritarian measures. There is still a lingering suspicion of Catholics because of their association with South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem’s anti-communist regime in the 1950s and ’60s, but new priests have been ordained and new churches opened.

As memories of the war recede, three major forces are driving U.S.-Vietnam relations: China, money and American ideals.

Vietnam and the United States share a strong interest in preventing the expansion of Chinese power in Asia. Even after the 1979 war, China continued to lob artillery shells across the border until Vietnam withdrew from Cambodia 10 years later. In 2000, China drove a hard bargain on border adjustment, establishing border markers hundreds of yards south of the old ones. China is also in disputes with Vietnam over competing claims for waters and territory in the Gulf of Tonkin and the South China Sea. Chinese military patrols and militarized facilities in those areas buttress those claims, and China frequently challenges Vietnamese vessels in international waters.

Meanwhile, Vietnam was becoming increasingly dependent on China for its economic well-being as cheap Chinese goods replaced Vietnamese production. But Hanoi has now established an “omni-directional” foreign policy to reduce that dependence and strengthen ties with other nations, especially the United States.

There has been an increase in high-level American visits to Vietnam, more trade and investment ties, and U.S. Navy calls at Vietnamese ports, including the March 2018 arrival of the aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson at Da Nang. In October 2016, two Navy vessels docked in Cam Ranh Bay, just as Prime Minister Dong had predicted in 1975. Vietnam even participated in the U.S.-sponsored Rim of the Pacific training exercises in 2018.

Vietnamese taste for money has also driven postwar relations. In the early postwar years, Vietnam used the remains of U.S. servicemen to extract American money.

In March 1977, for example, I accompanied a five-member presidential commission, appointed by Jimmy Carter and led by United Auto Workers President Leonard Woodcock, on a mission to get more information on MIAs and seek improved relations with Vietnam. We toured Hanoi’s Bach Mai hospital, which had likely been hit by a stray bomb during the war, and Vietnamese officials accompanying us emphasized their expectation that U.S. aid should be forthcoming “to heal the wounds of war.”

Subsequent years saw significant payments for mine clearing and Agent Orange-related health problems, as well as humanitarian and economic aid totaling more than $100 million annually. However, American businesses participating in the mushrooming trade and investment opportunities have experienced some obstacles along the way, including demands for bribes, such as those rejected by a company I represented.

The third driver of U.S.-Vietnamese relations, American ideals, has seen mixed success. Before leaving for Vietnam in 1975, I met with Southeast Asia expert Kenneth Landon, a professor at American University in Washington, D.C., and my dissertation adviser when I earned a doctorate in international relations in 1974. We discussed his experience living in Ho Chi Minh’s house in 1946, when the Vietnamese leader told Landon that his desire for independence was based upon the U.S. Constitution. Landon believed Ho Chi Minh was indeed a communist, but nonetheless a nationalist first.

With the exception of one avid Marxist at Hanoi University, I found that to be true of every Vietnamese official I met, even those at Communist Party headquarters who looked to the United States as a patron—a “city on the hill” that could help Vietnam in the future.

In 1993, I had the opportunity to teach at Vietnam’s Institute for International Relations, an educational arm of the Foreign Ministry for midlevel diplomats and military officers. One day I started to quote Abraham Lincoln’s “government of the people, by the people, and for the people” from the Gettysburg Address, but was interrupted by students who quoted the entire statement by heart.

Vietnam has trended toward American ideals, but recent crackdowns on internet freedom and opponents of Communist Party policy constitute a step backward, perhaps due to the reduced U.S. emphasis on human rights, but likely reflecting Politburo fear of independent-minded Vietnamese citizens and groups.

A few years ago I left Vietnam for the last time. I am now too old to return to former battlefields and friends. But to those who sacrificed and shed blood in the war, I can only offer a word of encouragement as we, the living, pray for our departed brothers and sisters on all sides, in hopes for a better future that, despite recent bumps, has already begun to appear.

—Hank Kenny, a West Point graduate, served in Vietnam as a U.S. Army captain for two tours: 5th Special Forces Group, November 1965-November 1966; and company commander, 5th Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment, 199th Light Infantry Brigade, February-April 1968, when he lost his left leg to enemy fire.