The Drum Barracks

Civil War Museum

1052 N. Banning Boulevard

Wilmington, CA 90744

310-548-7509

drumbarracks.org

Tour Schedule (guided tours only)

Tuesday–Thursday: 10 a.m.–11:30 a.m.

Saturday–Sunday: 11:30 a.m. and 1 p.m.

Accessibility: There is no elevator.

Those unable to access the second floor are invited to watch a video tour of the upstairs exhibits.

You won’t find Wilmington, Calif., high on most lists of must-see Civil War locales. A visit to Wilmington’s Drum Barracks Civil War museum—about 20 miles south of Los Angeles, on the Pacific coast—might change a lot of minds, however. The museum does a wonderful job of shining light on the underappreciated role California and the Southwest Borderlands played during the war.

Named for Lt. Col. Richard Coulter Drum, adjutant general of the Department of the Pacific, Drum Barracks was Union Army headquarters for Southern California and the Arizona Territory between 1862 and 1871 (Wilmington was known as San Pedro at the time). Troops there were mainly responsible for guarding San Pedro Harbor, which was used for Federal shipments of gold, supplies, and soldiers. They also helped protect locals from Southern sympathizers intent on taking control of the region. In 1859, Californians had voted to split the state in two via the Pico Act. Had Congress approved the legislation at the time, the budding Confederacy could have gained another state from which to acquire funding, supplies, and soldiers.

The museum today is located in what served as the junior officers quarters, the only remaining wooden building of 22 that were once part of a 60-acre post. Bricks from the site’s original chimneys, dismantled for safety from earthquakes long ago, were repurposed for courtyard walkways.

Although remote geographically, California made meaningful contributions during the war. A timeline at the museum presents an overview of California history showing political, economic, military, demographic facts, and California “firsts” as themes. Gold from California, for example, is estimated to have financed 25 percent of the Union war effort.

The California Room tells the story of the California Column. Organized by Colonel James H. Carleton, commander of Drum Barracks, the column consisted of more than 2,300 troops, who mobilized at Fort Yuma, Calif., and marched to El Paso, Texas, to stop Confederate attempts to capture New Mexico Territory and beyond. By the end of the war, California had supplied more than 17,000 volunteers, 8,000 of whom were mustered through the Drum Barracks.

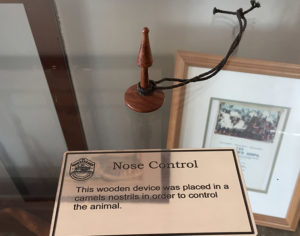

The museum also highlights the use of camels during the war. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis had imported the ruminants in the mid-1850s, believing they would make better pack animals than horses in the dry Southwestern climate. In 1862, Drum Barracks received 36 camels, but the experiment ultimately failed because they proved incompatible with horses (the museum’s Armory Room displays a camel’s nose plug used for directional purposes) and for a lack of funding. By 1863, the animals had been sold off.

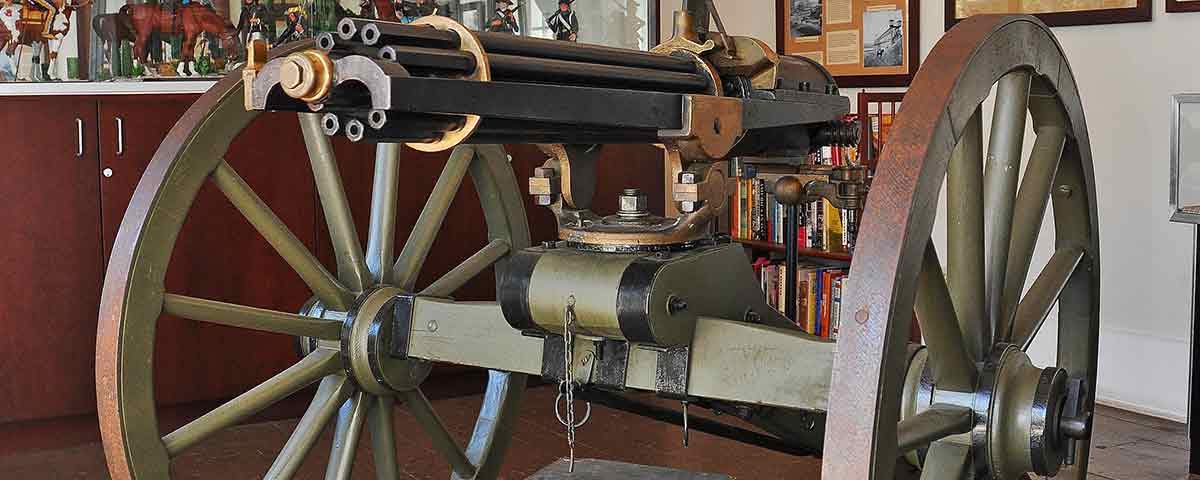

A Gatling gun is the centerpiece of the museum’s Technology Room, dedicated to advances in warfare. The story of the Drum Barracks Hospital, the main hospital for southern California and Arizona Territory servicemen, is also told. Among medical artifacts on display is a prosthetic leg that can be operated using pulleys and weights.

Enlisted men’s “cribs”—assembled using no nails and reproduced from the 1860 Army Barracks Regulations—are showcased as well. Reproduction and original leisure items used by soldiers are exhibited, including a cloth checkerboard with corncob playing pieces and Civil War stationery, as well as exhibits of firearms, uniforms, and McClellan saddles.

One of the more powerful exhibits is the story of Private William G. Stephens, who received the Medal of Honor for his contributions at Vicksburg on May 22, 1863. Displayed are a 34-star flag that Stephens found on the battlefield, his medal, and a document signed by President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton commending his service. Stephens’ family moved to California and presented his belongings to the museum.

A research library and a nice gift shop are also onsite.