An American pilot’s introduction to World War II on the far side of the world

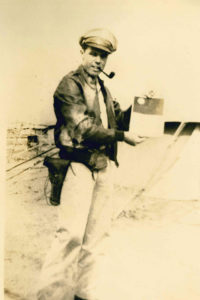

Sidney Garic (1919-2003) was born in New Orleans, Louisiana. In 1942, at age 22, he enlisted as a cadet in the U.S. Army Air Forces. In March 1943, at Moody Field, Valdosta, Georgia, he was commissioned a 2nd lieutenant and awarded pilot’s wings, whereupon he married his childhood sweetheart, Elaine von Behren. In October 1943, he arrived in Sookerating in the Assam valley of northeast India. At the stick of C-46 transport aircraft, he ferried troops, fuel, weapons, ammunition, food, and other supplies over the Himalayas from Assam to Kunming, capital of Yunnan Province, China. This high-altitude 625-mile transit, known as “flying the Hump,” was notorious for deadly turbulence. Garic’s narrative of his experiences as he completed his first flight into China was transcribed by his son, John, and edited by American History.

_____

The chart said we were over Kunming. Not so long and 7,000 miles ago, I’d been at home in Georgia—warm, belly full, relaxed, enjoying time with my new bride, who was happy that I would not be flying an armed aircraft. I didn’t mention that one of the points of a war was to shoot down transport planes. My crew and I had spent a week hopping the Pacific, usually at altitude. Now that we were closer to the ground, we were straining to see what was going on down there. Sometimes I’d tip our wings to give fellows a better look at roads curving like rope, forests like a fuzzy green blanket that gave way to farm country. As far as I could see, the earth was blocked off into neat squares, a patchwork quilt with no edges. Not so different from Kansas, I thought. Through

My adorable wife,

I’m writing this to you eight thousand feet in the air, aboard an airliner. We’re on our way to Miami, Fla., via air, by way of Chicago and Atlanta. My darling, I don’t quite know how to tell you what I have to say, but here goes. According to what we were told today in Reno, we’re on our way overseas, Miami, Fla. Being the last stop in the states. Darling, you can imagine how I feel, it hurts so terribly much, more than you’ll ever know, to go without seeing my adorable wife again. Today, after we received our orders, and we’re waiting for the plane, I went back to my room, and cried like a baby. Perhaps that was silly, but I was hoping so desperately that I would be able to see you once again before I left. [[CENSORED]] We’re being transferred from the Third OTU in Reno, to the Second Staging Squadron, ATC, Floridian Hotel, Miami, Fla., prior to depature, in preparation for overseas assignment. I don’t know how long we will stay in Miami, probably just a few days, before we will leave for overseas duty. While we’re there in Fla., we will be issued all of the necessary equipment for foreign service. That’s all I know at the moment, Honey, but I’ll write you every day, and let you know what’s happening. Darling, just as soon as I get to Miami, I’m going to do my best to get a leave, or if not, to find out how long we’ll be there and if it’s any length of time, I’ll send for you. My darling, I’ve just got to see you. I’ll try to phone you if I have a chance, too. Honey, under separate cover, I’m sending you my will, and also power of attorney, which will authorize you to endorse any government check that is made out to me. That way, you can endorse and cash any government check made out to me, by simply presenting this power of attorney. Honey, I told the Finance Office in Reno to forward my August pay check to you. So when it comes, just take it to the bank, together with the power of attorney, and cash it, or deposit it to our account, whichever you wish. Honey, take good care of that power of attorney, because without it my government checks made out to me, that you might receive, are no good unless they can be endorsed by you or me. According to what the legal department in Reno told me, Louisiana has some law about wills of men in the service, and hence I had to write it all out myself, but it’s all correct and proper. So, Honey, put it with the rest of our things for safekeeping. My darling, please try and behave, and pray for our life together to begin soon. It will help so much to know that you are all right, and are being well taken care of. Please try not to worry about me, darling, I’ll be as well as I can be, without the most important person in my life with me. Honey, can you write to me in Miami at that address I gave you on Page 2? Please write to me, darling, your letters are all I have now. My darling, I have to stop now. I’ll write again tomorrow. Sweetheart, please, please, always remember that I love you, no matter what happens. My love for you is the only thing that keeps me going. Goodnight, my darling wife, please wait for me. Mizpah.

Your adoring husband, Sid

EDITOR’S NOTE: In Hebrew “Mizpah” means “May the Lord keep watch between you and me when we are away from each other.” (Genesis 31:49)

my headset I could hear guys saying what I was thinking. I banked to land and started zigzagging—standard war zone procedure. “What the heck is going on down there?” said my co-pilot. I banked the other way and looked down. I had to blink to make sure I didn’t have dust in my eyes.

People—Chinese, I guessed—were working on the runway we were about to land on. That wasn’t unusual. Runways were going in all over; so much of the war was being  fought in the air. What was unusual at Kunming was the method. Thousands of people—no, tens of thousands—no bulldozers or graders, no cranes, just people, all moving in different directions, working like ants, as if they were making a runway out of people. Were they going to lie down and let us land on them? I shook my head and focused on setting the plane down. As I made our final approach, the people on the runway began dashing off to either side.

fought in the air. What was unusual at Kunming was the method. Thousands of people—no, tens of thousands—no bulldozers or graders, no cranes, just people, all moving in different directions, working like ants, as if they were making a runway out of people. Were they going to lie down and let us land on them? I shook my head and focused on setting the plane down. As I made our final approach, the people on the runway began dashing off to either side.

“Airbase, this is Transport 522,” I said into my headset. “I know you’ve cleared us to land, but it looks like they’re having trouble clearing the runway. Do you want us to wave off and go around again?”

The guy in the tower laughed. “Negative, 522,” he said. “Just come on in. They’ll get out of your way. Welcome to China, gentlemen.”

Sure enough, the workers got out of the way. We touched down, and as we rolled along I could make out men and women, even children, standing with shovels and rakes and hoes and picks, not concerned at all that a plane was landing so close. Every few hundred yards we passed an open fire with pots steaming over it and people waiting to eat. I taxied to where I was directed to park the plane. As the engines shut down, I told my crew, “Welcome to China, gentlemen.”

My joints ached from sitting so long. We climbed out and stretched and flexed and looked around. There was nothing to see, really. After turning in our orders and reporting our arrival, we rode in an open truck to a city of nothing but tents, except for Quonset huts that housed headquarters and the hospital. The truck stopped. A bored sergeant, half-saluting, assigned us tents. So much for my hope of sleeping inside.

Our tent reeked of mildewed canvas and dust until a breeze replaced that smell with the stink of rotten fish and burning tires. Closing the tent flaps made no difference. Before putting my gear on my bunk, I brushed at the dust, which rose and fell.

“Lunch, sirs,” the sullen sergeant said from outside as he worked his way down the line of tents. “Lunch truck heading out. Lunch, sirs.”

The truck brought us to an outdoor kitchen under a tarp, with hundreds of guys lining up on one side to get metal plates and utensils and guys with plates of food streaming out the other side. We hurried into line. I found myself among guys I didn’t know. My uniform was so much neater and cleaner than theirs it embarrassed me. The guys ahead and behind could tell I had just arrived, and they wanted to hear about home—the women, the food, the baseball. I wanted to hear about China, the airbase, the fighting. And what about those thousands of Chinese working on that runway?

Out of nowhere came a loud crack. Sniper, I thought, as everyone else hit the ground ahead of me. Soldiers and medics converged on where I lay. “Make room, men,” someone said. “C’mon, let ’em through!” The guy ahead of me got up, so I did, too. My chest hurt where I’d landed on my metal plate. All the other guys got up, too—except one, who lay in the dirt, face up, eyes open. Under his head a pool of blood was spreading. “He’s had it,” somebody said. What happened what happened what happened, the line buzzed. Medics were checking the poor sucker, not doing much except covering his head with a towel. Blood soaked the towel.

A military policeman came over. “Idiot over thataway was cleaning his pistol,” the MP told the medics, pointing toward our part of the tent city. “Didn’t know a round was in the chamber, I think. Poor bastard.” I couldn’t tell if he meant the dead man or the idiot.

Medics put the dead man on a stretcher, covered him, and loaded him onto a jeep. When they drove off, the lunch line reassembled. I could barely breathe, but the line surged toward the kitchen, carrying me along. We stepped around the blood-soaked patch with the dead man’s plate lying where he’d dropped it. My uniform had gotten dirty. I looked just like everybody else. The lunch line shuffled forward. We never did hear what happened to the guy who had been cleaning his loaded gun.

Welcome to China, gentlemen.

_____

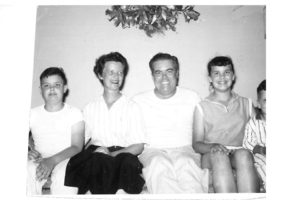

Sidney Garic flew 99 round trips over the Hump, and began many other flights that he had to abort owing to weather or mechanical difficulties, including engine failure, loss of oil pressure, and fires in the electrical

system or engines. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in August 1944. Upon completing his overseas tour he returned stateside to train as an instructor pilot in Brownsville, Texas, and then at Bryan Field near College Station, Texas. When the war ended, Captain Garic was an Army Air Forces instrument pilot in Memphis, Tennessee. Upon mustering out, he began training as an air traffic controller in Memphis, but his mother got sick, so he returned to New Orleans, where he managed an appliance and flooring wholesale company for 35 years. He and Elaine had three children—Tom, Sue, and John. Many years passed before he explained to Elaine what prize targets transports had been, or about how easy it was in a war zone to killed standing in line for lunch.